Two Visions: Emily Carr & Jack Shadbolt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liz Magor I Have Wasted My Life

Andrew Kreps 22 Cortlandt Alley, Tue–Sat, 10 am–6 pm Tel. (212)741-8849 Gallery New York, NY 10013 andrewkreps.com Fax. (212)741-8163 Liz Magor I Have Wasted My Life May 21 - July 3 Opening Reception: Friday, May 21, 4 - 7 pm Andrew Kreps Gallery is pleased to announce I Have Wasted My Life, an exhibition of new works by Liz Magor at 22 Cortlandt Alley. On the wall, a new sculpture titled Perennial is formed from a duffle coat, which in the 1960s and 1970s had become a de-facto uniform for student protestors, including those part of the nascent environmental movement in Vancouver, where Greenpeace was founded in 1971. A near artifact from this time, the coat carries with it the accumulated wear from these actions. The artist’s own interventions seek to repair the garment, though in lieu of erasure, Magor marks the damage using paint, ink, and sculptural material. Simultaneously, Magor adds vestiges of the coat’s past activity, such as two cookies cast in gypsum placed in its pocket to resuscitate it to its prior use. Magor often positions humble objects at the center of her sculptures, the stuff that plays fleeting roles in our lives as repositories for memories and affection before being replaced. Three found workbenches, positioned throughout the galleries, become stages for these objects, suggesting sites for their rehabilitation. On each, a meticulously molded and cast toy animal rests between an array of accumulated items that range from the deeply personal, such as small collections of rocks, shells, and dried flowers, to those that are ubiquitous, such as Ikea Lack furniture, which is produced in a way that it is no longer contained to one place, or time. -

Borderline Research

Borderline Research Histories of Art between Canada and the United States, c. 1965–1975 Adam Douglas Swinton Welch A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Adam Douglas Swinton Welch 2019 Borderline Research Histories of Art between Canada and the United States, c. 1965–1975 Adam Douglas Swinton Welch Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Taking General Idea’s “Borderline Research” request, which appeared in the first issue of FILE Megazine (1972), as a model, this dissertation presents a composite set of histories. Through a comparative case approach, I present eight scenes which register and enact larger political, social, and aesthetic tendencies in art between Canada and the United States from 1965 to 1975. These cases include Jack Bush’s relationship with the critic Clement Greenberg; Brydon Smith’s first decade as curator at the National Gallery of Canada (1967–1975); the exhibition New York 13 (1969) at the Vancouver Art Gallery; Greg Curnoe’s debt to New York Neo-dada; Joyce Wieland living in New York and making work for exhibition in Toronto (1962–1972); Barry Lord and Gail Dexter’s involvement with the Canadian Liberation Movement (1970–1975); the use of surrogates and copies at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (1967–1972); and the Eternal Network performance event, Decca Dance, in Los Angeles (1974). Relying heavily on my work in institutional archives, artists’ fonds, and research interviews, I establish chronologies and describe events. By the close of my study, in the mid-1970s, the movement of art and ideas was eased between Canada and the United States, anticipating the advent of a globalized art world. -

Marian Penner Bancroft Rca Studies 1965

MARIAN PENNER BANCROFT RCA STUDIES 1965-67 UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, Arts & Science 1967-69 THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL OF ART (Emily Carr University of Art + Design) 1970-71 RYERSON POLYTECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, Toronto, Advanced Graduate Diploma 1989 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, Visual Arts Summer Intensive with Mary Kelly 1990 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, short course with Griselda Pollock SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, upcoming in May 2019 WINDWEAVEWAVE, Burnaby, BC, video installation, upcoming in May 2018 HIGASHIKAWA INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL GALLERY, Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan, Overseas Photography Award exhibition, Aki Kusumoto, curator 2017 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, RADIAL SYSTEMS photos, text and video installation 2014 THE REACH GALLERY & MUSEUM, Abbotsford, BC, By Land & Sea (prospect & refuge) 2013 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HYDROLOGIC: drawing up the clouds, photos, video and soundtape installation 2012 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, SPIRITLANDS t/Here, Grant Arnold, curator 2009 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, CHORUS, photos, video, text, sound 2008 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HUMAN NATURE: Alberta, Friesland, Suffolk, photos, text installation 2001 CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver THE MENDEL GALLERY, Saskatoon SOUTHERN ALBERTA ART GALLERY, Lethbridge, Alberta, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) 2000 GALERIE DE L'UQAM, Montreal, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver, VISIT 1999 PRESENTATION HOUSE GALLERY, North Vancouver, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) UNIVERSITY -

![[Carr – Bibliography]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1319/carr-bibliography-401319.webp)

[Carr – Bibliography]

Bibliography Steven C. McNeil, with contributions by Lynn Brockington Abell, Walter, “Some Canadian Moderns,” Magazine of Art 30, no. 7 (July 1937): 422–27. Abell, Walter, “New Books on Art Reviewed by the Editors, Klee Wyck by Emily Carr,” Maritime Art 2, no. 4 (Apr.–May 1942): 137. Abell, Walter, “Canadian Aspirations in Painting,” Culture 33, no. 2 (June 1942): 172–82. Abell, Walter, “East Is West – Thoughts on the Unity and Meaning of Contemporary Art,” Canadian Art 11, no. 2 (Winter 1954): 44–51, 73. Ackerman, Marianne, “Unexpurgated Emily,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 16 Aug. 2003. Adams, James, “Emily Carr Painting Is Sold for $240,000,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 28 Nov. 2003. Adams, John, “…but Near Carr’s House Is Easy Street,” Islander, supplement to the Times- Colonist (Victoria), 7 June 1992. Adams, John, “Emily Walked Familiar Routes,” Islander, supplement to the Times-Colonist (Victoria), 26 Oct. 1993. Adams, John, “Visions of Sugar Plums,” Times-Colonist (Victoria), 10 Dec. 1995. Adams, Sharon, “Memories of Emily, an Embittered Artist,” Edmonton Journal, 27 July 1973. Adams, Timothy Dow, “‘Painting Above Paint’: Telling Li(v)es in Emily Carr’s Literary Self- Portraits,” Journal of Canadian Studies 27, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 37–48. Adeney, Jeanne, “The Galleries in January,” Canadian Bookman 10, no. 1 (Jan. 1928): 5–7. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Oil Paintings from the Emily Carr Trust Collection (ex. cat.). Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1958. Art Gallery of Ontario, Emily Carr: Selected Works from the Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery (ex. cat.). Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1974. -

Post-War & Contemporary

post-wAr & contemporAry Art Sale Wednesday, november 21, 2018 · 4 Pm · toronto i ii Post-wAr & contemPorAry Art Auction Wednesday, November 21, 2018 4 PM Post-War & Contemporary Art 7 PM Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art Design Exchange The Historic Trading Floor (2nd floor) 234 Bay Street, Toronto Located within TD Centre Previews Heffel Gallery, Calgary 888 4th Avenue SW, Unit 609 Friday, October 19 through Saturday, October 20, 11 am to 6 pm Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Saturday, October 27 through Tuesday, October 30, 11 am to 6 pm Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Thursday, November 8 through Saturday, November 10, 11 am to 6 pm Design Exchange, Toronto The Exhibition Hall (3rd floor), 234 Bay Street Located within TD Centre Saturday, November 17 through Tuesday, November 20, 10 am to 6 pm Wednesday, November 21, 10 am to noon Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] APPrAisAls CONTACT [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com Absentee And telePhone bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shiPPing Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottAwA subscriPtions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-8884 montreAl CatAlogue subscriPtions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. -

A Review Essay

The enigma of emily carr A Review Essay LESLIE DAWN Unsettling Encounters: First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr Gerta Moray Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006. 400 pp. Illus. $75.00 cloth. Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon Charles C. Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom (Vancouver: Douglas & MacIntyre, with the National Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2006). 336 pp. Illus. $75.00 cloth. o Canadian artist has gen- struction of personal and na tional Nerated, or produced, more textual identities and the place of Aboriginal material than Emily Carr. That this peoples and cultures within them. is still true is evident from the two The exhibition catalogue contains books on the artist that appeared in eight essays by ten contributors from the summer of 2006. The National various disciplines, arranged more Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver or less chronologically. Ethnologists Art Gallery produced Emily Carr: Peter Macnair and Jay Stewart open New Perspectives on a Canadian by reinvestigating Carr’s 1907 tourist Icon, the catalogue for the latest excursion to Alaska, during which Carr retro spective. Concurrently, she formed the project for painting a UBC Press pub lished Gerta Moray’s documentary record of the poles of the long awaited monograph Unsettling Aboriginal villages of the Canadian Encounters: First Nations Imagery Northwest Coast. Contributing to the in the Art of Emily Carr. The two discussion on the veracity of Carr’s complementary studies combine the later autobiographical writings, they formats of lavishly illustrated coffee compare her published recollections table books with scholarly writings with archival records and the remaining that attempt defini tive statements on fragments of Carr’s missing Alaska this protean artist. -

The National Gallery of Canada: a Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:08 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions List and Index Garry Mainprize Volume 11, Number 1-2, 1984 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1074332ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar See table of contents Publisher(s) UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mainprize, G. (1984). The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 11(1-2), 3–78. https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Association d'art des universités du Canada), 1984 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions — List and Index — GARRY MAINPRIZE Ottawa The National Gallerv of Canada can date its February 1916, the Gallery was forced to vacate foundation to the opening of the first exhibition of the muséum to make room for the parliamentary the Canadian Academy of Arts at the Clarendon legislators. -

Canadian, Impressionist & Modern

CanAdiAn, impressionist & modern Art Sale Wednesday, december 2, 2020 · 4 pm pt | 7 pm et i Canadian, impressionist & modern art auCtion Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Heffel’s Digital Saleroom Post-War & Contemporary Art 2 PM Vancouver | 5 PM Toronto / Montreal Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art 4 PM Vancouver | 7 PM Toronto / Montreal previews By appointment Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Friday, October 30 through Wednesday, November 4, 11 am to 6 pm PT Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Monday, November 16 through Saturday, November 21, 11 am to 6 pm ET Heffel Gallery, Toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue Together with our Yorkville exhibition galleries Thursday, November 26 through Tuesday, December 1, 11 am to 6 pm ET Wednesday, December 2, 10 am to 3 pm ET Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” Consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] appraisals CONTACt [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com absentee, telephone & online bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shipping Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottawa subsCriptions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-6505 montreal Catalogue subsCriptions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. An Annual Subscription entitles vanCouver you to receive our Auction Catalogues and Auction Result Sheets. 2247 Granville Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6H 3G1 Our Annual Subscription Form can be found on page 103 of this Telephone 604-732-6505, Fax 604-732-4245 catalogue. -

Leisure and Pleasure As Modernist Utopian D3eal: the Drawings and Paintings by B.C.Binning from the Mid 1940S to the Early 1950S

LEISURE AND PLEASURE AS MODERNIST UTOPIAN D3EAL: THE DRAWINGS AND PAINTINGS BY B.C.BINNING FROM THE MID 1940S TO THE EARLY 1950S by KAORI YAMANAKA B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1999 © Kaori Yamanaka, 1999 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date A(^i( 30, DE-6 (2/88) 11 Abstract Bertram Charles Binning's depiction of British Columbia coastal scenes in his drawings and paintings of the mid 1940s to the early 1950s present images of sunlit seascapes in recreational settings; they are scenes of leisure and pleasure. The concern for leisure and pleasure was central to the artist's modernism, even after he began painting in a semi-abstract manner around 1948. In this particular construction of modernism, Binning offered pleasure as an antidote to some of the anxieties he observed in postwar culture. -

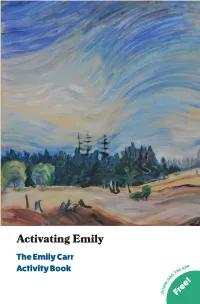

Activating Emily

Activating Emily The Emily Carr P AP Activity Book HE T D A O L N W O D Free! This book has a life of its own! Colour and draw in it, “activate” it with your tablet or phone, and take it on a field trip! Tell your friends about it! Use your device to take photos of your work throughout this book, and share them on Instagram and Twitter with the hashtag #ActivatingEmily. The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria is located on the traditional territories of the Lekwungen peoples, today known as the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations. We are grateful for the opportunity to live and learn on this territory. Looking at Emily Carr p. 3 With the Whole Body For the Love of Nature p. 8 Emily’s Colours p. 10 The New Canadian p. 14 Field Trips! p. 17 Look for these corners! In conjunction with this book, the Activating Emily companion app provides an interactive experience with Emily Carr’s art. Look for artworks and images framed by corners like these. Download the app to your tablet or mobile device, open it, and follow the on-screen instructions to scan these pieces. There you’ll find additional videos, stories and more! Get the Activating Emily app for FREE on your iOS device now from the iTunes App Store, or visit the Gallery welcome desk to sign out a device to use. In some low-light areas of the Gallery the pieces might be more difficult to scan. Try shifting your angle of view or repositioning yourself for more light and better results. -

NATIONAL GALLERY of CANADA and the VANCOUVER ART GALLERY

Exhibition Reviews 157 Exhibition Reviews Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon . NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA and the VANCOUVER ART GALLERY. Mounted at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 2 June–4 September 2006. Accompanying publication: Charles Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom. Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon. Toronto: Douglas McIntyre, 2006. 335 p. ISBN 1-55365-173-1. Another exhibition about Emily Carr could not be unpopular , could it? Everyone, even schoolchildren, has at least heard of Emily Carr . As a child, I first noticed her when snooping through my father ’s art books, where I found Emily Carr, Her Paintings and Sketches, the exhibition catalogue for the 1945 memorial show put on after her death by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario. The odd cover image of fantastic totem creatures near bundled Native women made me look inside, and there I saw massive plasticine structures in the forms of buildings, trees, and columns. That moment of discovery bubbled up again when I entered the 2006 show , organ- ized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver Art Gallery. My anticipation grew, knowing that Emily Carr ’s paintings were waiting silently beyond the first doorway, simmering with their intensity and grandeur. The concept of this show was a key element of the Vancouver Art Gallery’s seventy-fifth anniversary plans, since the Emily Carr collection is an important part of the Gallery’ s holdings. What was planned was a fresh look at the artist that involved revisiting the major twentieth-century exhibitions that had formerly presented her work, an honest presentation that would rely on new sources and perhaps dispel or at least deflate myths or assumptions about the artist. -

The Group of Seven, AJM Smith and FR Scott Alexandra M. Roza

Towards a Modern Canadian Art 1910-1936: The Group of Seven, A.J.M. Smith and F.R. Scott Alexandra M. Roza Department of English McGill University. Montreal August 1997 A Thesis subrnitted to the Facdty of Graduate Studies and Researçh in partial fiilfiliment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. O Alexandra Roza, 1997 National Library BiMiotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtocl Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OttawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distnibuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. iii During the 19 los, there was an increasing concerted effort on the part of Canadian artists to create art and literature which would afhn Canada's sense of nationhood and modernity. Although in agreement that Canada desperately required its own culture, the Canadian artistic community was divided on what Canadian culture ought to be- For the majority of Canadian painters, wrïters, critics and readers, the fbture of the Canadian arts, especially poetry and painting, lay in Canada's past.