OBO Foundry in 2021: Operationalizing Open Data Principles to Evaluate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Zebrafish Anatomy and Stage Ontologies: Representing the Anatomy and Development of Danio Rerio

Van Slyke et al. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 2014, 5:12 http://www.jbiomedsem.com/content/5/1/12 JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL SEMANTICS RESEARCH Open Access The zebrafish anatomy and stage ontologies: representing the anatomy and development of Danio rerio Ceri E Van Slyke1*†, Yvonne M Bradford1*†, Monte Westerfield1,2 and Melissa A Haendel3 Abstract Background: The Zebrafish Anatomy Ontology (ZFA) is an OBO Foundry ontology that is used in conjunction with the Zebrafish Stage Ontology (ZFS) to describe the gross and cellular anatomy and development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio, from single cell zygote to adult. The zebrafish model organism database (ZFIN) uses the ZFA and ZFS to annotate phenotype and gene expression data from the primary literature and from contributed data sets. Results: The ZFA models anatomy and development with a subclass hierarchy, a partonomy, and a developmental hierarchy and with relationships to the ZFS that define the stages during which each anatomical entity exists. The ZFA and ZFS are developed utilizing OBO Foundry principles to ensure orthogonality, accessibility, and interoperability. The ZFA has 2860 classes representing a diversity of anatomical structures from different anatomical systems and from different stages of development. Conclusions: The ZFA describes zebrafish anatomy and development semantically for the purposes of annotating gene expression and anatomical phenotypes. The ontology and the data have been used by other resources to perform cross-species queries of gene expression and phenotype data, providing insights into genetic relationships, morphological evolution, and models of human disease. Background function, development, and evolution. ZFIN, the zebrafish Zebrafish (Danio rerio) share many anatomical and physio- model organism database [10] manually curates these dis- logical characteristics with other vertebrates, including parate data obtained from the literature or by direct data humans, and have emerged as a premiere organism to submission. -

Human Disease Ontology 2018 Update: Classification, Content And

Published online 8 November 2018 Nucleic Acids Research, 2019, Vol. 47, Database issue D955–D962 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1032 Human Disease Ontology 2018 update: classification, content and workflow expansion Lynn M. Schriml 1,*, Elvira Mitraka2, James Munro1, Becky Tauber1, Mike Schor1, Lance Nickle1, Victor Felix1, Linda Jeng3, Cynthia Bearer3, Richard Lichenstein3, Katharine Bisordi3, Nicole Campion3, Brooke Hyman3, David Kurland4, Connor Patrick Oates5, Siobhan Kibbey3, Poorna Sreekumar3, Chris Le3, Michelle Giglio1 and Carol Greene3 1University of Maryland School of Medicine, Institute for Genome Sciences, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 3University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA, 4New York University Langone Medical Center, Department of Neurosurgery, New York, NY, USA and 5Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA Received September 13, 2018; Revised October 04, 2018; Editorial Decision October 14, 2018; Accepted October 22, 2018 ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The Human Disease Ontology (DO) (http://www. The rapid growth of biomedical and clinical research in re- disease-ontology.org), database has undergone sig- cent decades has begun to reveal novel cellular, molecular nificant expansion in the past three years. The DO and environmental determinants of disease (1–4). However, disease classification includes specific formal se- the opportunities for discovery and the transcendence of mantic rules to express meaningful disease mod- knowledge between research groups can only be realized in conjunction with the development of rigorous, standard- els and has expanded from a single asserted clas- ized bioinformatics tools. These tools should be capable of sification to include multiple-inferred mechanistic addressing specific biomedical data nomenclature and stan- disease classifications, thus providing novel per- dardization challenges posed by the vast variety of biomed- spectives on related diseases. -

The Evaluation of Ontologies: Editorial Review Vs

The Evaluation of Ontologies: Editorial Review vs. Democratic Ranking Barry Smith Department of Philosophy, Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Life Sciences, and National Center for Biomedical Ontology University at Buffalo from Proceedings of InterOntology 2008 (Tokyo, Japan, 26-27 February 2008), 127-138. ABSTRACT. Increasingly, the high throughput technologies used by biomedical researchers are bringing about a situation in which large bodies of data are being described using controlled structured vocabularies—also known as ontologies—in order to support the integration and analysis of this data. Annotation of data by means of ontologies is already contributing in significant ways to the cumulation of scientific knowledge and, prospectively, to the applicability of cross-domain algorithmic reasoning in support of scientific advance. This very success, however, has led to a proliferation of ontologies of varying scope and quality. We define one strategy for achieving quality assurance of ontologies—a plan of action already adopted by a large community of collaborating ontologists—which consists in subjecting ontologies to a process of peer review analogous to that which is applied to scientific journal articles. 1 From OBO to the OBO Foundry Our topic here is the use of ontologies to support scientific research, especially in the domains of biology and biomedicine. In 2001, Open Biomedical Ontologies (OBO) was created by Michael Ashburner and Suzanna Lewis as an umbrella body for the developers of such ontologies in the domain of the life sciences, applying the key principles underlying the success of the Gene Ontology (GO) [GOC 2006], namely, that ontologies be (a) open, (b) orthogonal, (c) instantiated in a well-specified syntax, and such as (d) to share a common space of identifiers [Ashburner et al. -

Applications of an Ontology Engineering Methodology Accessing Linked Data for Dialogue-Based Medical Image Retrieval

Applications of an Ontology Engineering Methodology Accessing Linked Data for Dialogue-Based Medical Image Retrieval Daniel Sonntag, Pinar Wennerberg, Sonja Zillner DFKI - German Research Center for AI, Siemens AG [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract of medication and treatment plan is foreseen. This requires This paper examines first ideas on the applicability of the medical images to be annotated accordingly so that the Linked Data, in particular a subset of the Linked Open Drug radiologists can obtain all the necessary information Data (LODD), to connect radiology, human anatomy, and starting with the image. Moreover, the image information drug information for improved medical image annotation needs to be interlinked in a coherent way to enable the and subsequent search. One outcome of our ontology radiologist to trace the dependencies between observations. engineering methodology is the semi-automatic alignment Linked Data has the potential to provide easier access to between radiology-related OWL ontologies (FMA and significantly growing, publicly available related data sets, RadLex). These can be used to provide new connections in such as those in the healthcare domain: in combination the medicine-related linked data cloud. A use case scenario with ontology matching and speech dialogue (as AI is provided that involves a full-fletched speech dialogue system as AI application and additionally demonstrates the systems) this should allow medical experts to explore the benefits of the approach by enabling the radiologist to query interrelated data more conveniently and efficiently without and explore related data, e.g., medical images and drugs. having to switch between many different applications, data The diagnosis is on a special type of cancer (lymphoma). -

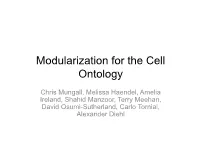

Modularization for the Cell Ontology

Modularization for the Cell Ontology Chris Mungall, Melissa Haendel, Amelia Ireland, Shahid Manzoor, Terry Meehan, David Osumi-Sutherland, Carlo Torniai, Alexander Diehl Outline • The Cell Ontology and its neighbors • Handling multiple species • Extracting modules for taxonomic contexts • The Oort – OBO Ontology Release Tool Inter-ontology axioms Source Ref Axiom cl go ‘mature eosinophil’ SubClassOf capable of some ‘respiratory burst’ go cl ‘eosinophil differentiation’ EquivalentTo differentiation and has_target some eosinophil * cl pro ‘Gr1-high classical monocyte’ EquivalentTo ‘classical monocyte’ and has_plasma_membrane_part some ‘integrin-alpha-M’ and …. cl chebi melanophage EquivalentTo ‘tissue-resident macrophage’ and has_part some melanin and … cl uberon ‘epithelial cell of lung’ EquivalentTo ‘epithelial cell’ and part_of some lung uberon cl muscle tissue EquivalentTo tissue and has_part some muscle cell clo cl HeLa cell SubClassOf derives_from some (‘epithelial cell’ and part_of some cervix) fbbt cl fbbt:neuron EquivalentTo cl:neuron and part_of some Drosophila ** * experimental extension ** taxon-context bridge axiom The cell ontology covers multiple taxonomic contexts Ontology Context # of links to cl MA adult mouse 1 FMA adult human 658 XAO frog 63 AAO amphibian ZFA zebrafish 391 TAO bony fish 385 FBbt fruitfly 53 PO plants * CL all cells - Xref macros: an easy way to formally connect to broader taxa treat-xrefs-as-genus-differentia: CL part_of NCBITaxon:7955! …! [Term]! id: ZFA:0009255! name: amacrine cell! xref: CL:0000561! -

Investigating Term Reuse and Overlap in Biomedical Ontologies Maulik R

Investigating Term Reuse and Overlap in Biomedical Ontologies Maulik R. Kamdar, Tania Tudorache, and Mark A. Musen Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research, Department of Medicine, Stanford University ABSTRACT CT, to spare the effort in creating already existing quality We investigate the current extent of term reuse and overlap content (e.g., the anatomy taxonomy), to increase their among biomedical ontologies. We use the corpus of biomedical interoperability, and to support its use in electronic health ontologies stored in the BioPortal repository, and analyze three types records (Tudorache et al., 2010). Another benefit of the of reuse constructs: (a) explicit term reuse, (b) xref reuse, and (c) ontology term reuse is that it enables federated search Concept Unique Identifier (CUI) reuse. While there is a term label engines to query multiple, heterogeneous knowledge sources, similarity of approximately 14.4% of the total terms, we observed structured using these ontologies, and eliminates the need for that most ontologies reuse considerably fewer than 5% of their extensive ontology alignment efforts (Kamdar et al., 2014). terms from a concise set of a few core ontologies. We developed For the purpose of this work, we define as term reuse an interactive visualization to explore reuse dependencies among the situation in which the same term is present in two or biomedical ontologies. Moreover, we identified a set of patterns that more ontologies either by direct use of the same identifier, indicate ontology developers did intend to reuse terms from other or via explicit references and mappings. We define as term ontologies, but they were using different and sometimes incorrect overlap the situation in which the term labels in two or more representations. -

Ontology: Tool for Broad Spectrum Knowledge Integration Barry Smith

Foreword to Chinese Translation Ontology: Tool for Broad Spectrum Knowledge Integration Barry Smith BFO: The Beginnings This book was first published in 2015. Its primary target audience was bio- and biomedical informaticians, reflecting the ways in which ontologies had become an established part of the toolset of bio- and biomedical informatics since (roughly) the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP). As is well known, the success of HGP led to the transformation of biological and clinical sciences into information-driven disciplines and spawned a whole series of new disciplines with names like ‘proteomics’, ‘connectomics’ and ‘toxiocopharmacogenomics’. It was of course not only the human genome that was made available for research but also the genomes of other ‘model organisms’, such as mouse or fly. The remarkable similarities between these genomes and the human genome made it possible to carry out experiments on model organisms and use the results to draw conclusions relevant to our understanding of human health and disease. To bring this about, however, it was necessary to create a controlled vocabulary that could be used for describing salient features of model organisms in a species-neutral way, and to use the terms of this vocabulary to tag the sequence data for all salient organisms. It was with the purpose of creating such a vocabulary that the Gene Ontology (GO) was born in a Montreal hotel bar in 1998.1 Since then the GO has served as mediator between the new genomic data on the one hand, which is accessible only with the aid of computers, and what we might think of as the ‘old biology data’ captured using natural language by means of terms such as ‘cell division’ or ‘mitochondrion’ or ‘protein binding’. -

OLOBO: a New Ontology for Linking and Integrating Open Biological

OLOBO: A new ontology for linking and integrating open biologi- cal and biomedical ontologies Edison Ong1, Yongqun He2,* 1 Department of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 2 Unit of Laboratory Animal Medicine, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and Center of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT other ontology terms. To integrate all the ontologies, we To link and integrate different Open Biological and Biomedical first identified and collected all ontology terms shared by at Ontologies (OBO) library ontologies, we generated an OLOBO on- tology that uses the Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) as the upper level least two ontologies. This step identified the minimal sets of ontology to align, link, and integrate all existing 9 formal OBO ontology terms shared by different ontologies. To notify Foundry ontologies. Our study identified 524 ontology terms shared from which ontology a term is imported, we generated a by at least two ontologies, which form the core part of OLOBO. Cur- rent OLOBO includes 978 ontology classes, 13 object properties, new annotation property called ‘term from ontology’ and 90 annotation properties. OLOBO was queried, analyzed, and (OLOBO_0000001). Next, we used Ontofox (Xiang et al., applied to identify potential deprecated terms and discrepancy 2010) to identify terms and axioms related to extracted on- among different OBO library ontologies. tology terms. To align with BFO, we manually examined ontologies and ensure appropriate upper level terms added 1 INTRODUCTION for the purpose of ontology linkage and integration. The OBO Foundry aims at establishing a set of ontology development principles (e.g., openness, collaboration) and 2.3 OLOBO source code, deposition, and queries incorporating ontologies following these principles in an The OLOBO source code is openly available at GitHub: evolving non-redundant suite (Smith et al., 2007). -

Instructions for the Preparation of a Camera-Ready Paper in MS Word

Ontobee: A Linked Data Server that publishes RDF and HTML data simultaneously Editor(s): Name Surname, University, Country Solicited review(s): Name Surname, University, Country Open review(s): Name Surname, University, Country Zuoshuang Xianga, Chris Mungallb, Alan Ruttenbergc, Yongqun Hea,* aUniversity of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48105, USA. bLawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley CA, USA, 48109, cUniversity at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA Abstract. The Semantic Web allows machines to understand the meaning of information on the World Wide Web. The Link- ing Open Data (LOD) community aims to publish various open datasets as RDF on the Web. To support Semantic Web and LOD, one basic requirement is to identify individual ontology terms as HTTP URIs and deference the URIs as RDF files through the Web. However, RDF files are not as good as HTML for web visualization. We propose a novel “RDF/HTML 2in1” model that aims to report the RDF and HTML results in one integrated system. Based on this design, we developed On- tobee (http://www.ontobee.org/), a web server aimed to dereference ontology term URIs with RDF file source code output and HTML visualization on the Web and to support ontology term browsing and querying. Using SPARQL query of RDF triple stores, Ontobee first provides a RDF/XML source code for a particular HTTP URI referring an ontology term. The RDF source code provides a link using XSLT technology to a HTML code that generates HTML visualization. This design will allow a web browser user to read the HTML display and simultaneously allow a web application to access the RDF document. -

ECO, the Evidence & Conclusion Ontology

D1186–D1194 Nucleic Acids Research, 2019, Vol. 47, Database issue Published online 8 November 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1036 ECO, the Evidence & Conclusion Ontology: community standard for evidence information Michelle Giglio1,*, Rebecca Tauber1, Suvarna Nadendla1, James Munro1, Dustin Olley1, Shoshannah Ball1, Elvira Mitraka1, Lynn M. Schriml 1, Pascale Gaudet 2, Elizabeth T. Hobbs3, Ivan Erill3, Deborah A. Siegele4, James C. Hu5, Chris Mungall6 and Marcus C. Chibucos1 1Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA, 2Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Department of Biological Sciences, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA, 4Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77840, USA, 5Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77840, USA and 6Molecular Ecosystems Biology, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received September 14, 2018; Revised October 12, 2018; Editorial Decision October 15, 2018; Accepted October 16, 2018 ABSTRACT biomolecular sequence, phenotype, neuroscience, behav- ioral, medical and other data. The process of biocuration The Evidence and Conclusion Ontology (ECO) con- involves making one or more descriptive statements about tains terms (classes) that describe types of evi- a biological/biomedical entity, for example that a protein dence and assertion methods. ECO terms are used performs a particular function, that a specific position in in the process of biocuration to capture the evidence DNA is methylated, that a particular drug causes an adverse that supports biological assertions (e.g. gene prod- effect or that bat wings and human arms are homologous. uct X has function Y as supported by evidence Z). -

Manufacturing Barry Smith Third Workshop on an Open Knowledge Network Manufacturing Community of Practice

Manufacturing Barry Smith Third Workshop on an Open Knowledge Network Manufacturing Community of Practice • Barry Smith, National Center for Ontological Research • John Milinovich, Pinterest • William Regli, DARPA • Ram Sriram, NIST • Ruchari Sudarsan, DOE http://ncorwiki.buffalo.edu/index.php/manufacturing_community_of_practice First use case: Manufacturing capabilities of companies, equipment, sensors, persons, teams ... • Use case: risk mitigation in supply-chain management -- screening to select suitable suppliers for example when accepted bidder drops out • In progress: scraping information on the webpages of manufacturing companies and mapping identified terms to ontologies to enable reasoning (Farhad Ameri, Collaborative agreement between NIST and Texas State) • Can we create wikipedia-like pages for each company from this activity? Relevant: • manufacturing readiness levels (MRL) • workforce development (DFKI) • of interest also to DOD • generalizable to other domains (medicine, research …) Second use case: Manufactured products • what exists are primarily NLP-based attempts to identify emerging trends in customer needs or markets, for example from the study of Amazon reviews of products • NIST Core Product Model • Can we convert into an OKN? • What would be benefits / synergies: • food • synergy between manufacturing and health – allergy, addiction, food safety… • synergy with smart cities/geosciences – obesity, food access, … • synergy with capabilities use case (what are the capabilities of products)? Third use case: Patents • to enable enhanced patent search resolving terminological inconsistencies • this too will require ontology of capabilities Fourth use case: manufacturing uses of robots, sensors, … • Probably not enough data in the public domain to enable a useful OKN for robot use in manufacturing at this stage Fifth use case: Promoting interoperability in smart manufacturing • Smart manufacturing works for CAD. -

Semi-Automated Ontology Generation for Biocuration and Semantic Search

Semi-automated Ontology Generation for Biocuration and Semantic Search Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) vorgelegt an der Technischen Universität Dresden Fakultät Informatik von Dipl.-Inf. Thomas Wächter geboren am 25. August 1978 in Jena Betreuender Hochschullehrer: Prof. Dr. Michael Schroeder Technische Universität Dresden Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Lawrence Hunter University of Colorado, Denver/Boulder, USA Tag der Einreichung: 04. 06. 2010 Tag der Verteidigung: 27. 10. 2010 Abstract Background: In the life sciences, the amount of literature and experimental data grows at a tremendous rate. In order to effectively access and integrate these data, biomedical ontologies – controlled, hierarchical vocabularies – are being developed. Creating and maintaining such ontologies is a difficult, labour-intensive, manual process. Many computational methods which can support ontology construction have been proposed in the past. However, good, validated systems are largely miss- ing. Motivation: The biocuration community plays a central role in the development of ontologies. Any method that can support their efforts has the potential to have a huge impact in the life sciences. Recently, a number of semantic search engines were created that make use of biomedical ontologies for document retrieval. To transfer the technology to other knowledge domains, suitable ontologies need to be created. One area where ontolo- gies may prove particularly useful is the search for alternative methods to animal testing, an area where comprehensive search is of special interest to determine the availability or unavailability of alternative methods. Results: The Dresden Ontology Generator for Directed Acyclic Graphs (DOG4DAG) developed in this thesis is a system which supports the creation and extension of ontologies by semi-automatically generating terms, definitions, and parent-child re- lations from text in PubMed, the web, and PDF repositories.