'My School' and Others: Segregation and White Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selective High School 2021 Application

Stages of the placement process High Performing Students Team Parents read the application information online From mid-September 2019 Education Parents register, receive a password, log in, and then completeApplying and submit for the application Year online7 entry From 8 to selective high schools October 2019 to 11 November 2019 Parents request any disability provisions from 8 October to in 11 November 2019 2021 Principals provide school assessment scores From 19 November to Thinking7 December 2019 of applying for Key Dates Parents sent ‘Test authority’ letter On 27 Febru- ary 2020 a government selective Application website opens: Students sit the Selective High School 8 October 2019 Placementhigh Test forschool entry to Year 7for in 2021 Year On 12 7 March 2020 Any illness/misadventurein 2021?requests are submitted Application website closes: By 26 March 2020 10 pm, 11 November 2019 You must apply before this deadline. Last dayYou to change must selective apply high school online choices at: 26 April 2020 School selectioneducation.nsw.gov.au/public- committees meet In May and Test authority advice sent to all applicants: June 2020 27 February 2020 Placementschools/selective-high-schools- outcome sent to parents Overnight on 4 July and-opportunity-classes/year-7 Selective High School placement test: 2020 12 March 2020 Parents submit any appeals to principals By 22 July 2020 12 Parents accept or decline offers From Placement outcome information sent overnight on: July 2020 to at least the end of Term 1 2021 4 July 2020 13 Students who have accepted offers are with- drawn from reserve lists At 3 pm on 16 December 2020 14 Parents of successful students receive ‘Author- Please read this booklet carefully before applying. -

2020 Sydney Girls High School Annual Report

2020 Annual Report Sydney Girls High School 8138 Page 1 of 18 Sydney Girls High School 8138 (2020) Printed on: 28 April, 2021 Introduction The Annual Report for 2020 is provided to the community of Sydney Girls High School as an account of the school's operations and achievements throughout the year. It provides a detailed account of the progress the school has made to provide high quality educational opportunities for all students, as set out in the school plan. It outlines the findings from self-assessment that reflect the impact of key school strategies for improved learning and the benefit to all students from the expenditure of resources, including equity funding. School contact details Sydney Girls High School Moore Park Surry Hills, 2010 www.sydneygirl-h.schools.nsw.edu.au [email protected] 9331 2336 Message from the principal Despite the challenges of 2020 the school continued to deliver high level investment in the lives and learning of all students at Sydney Girls High. Appreciation is due to all staff, parents and student leaders who were significant in maintaining morale and close communication across the months of online learning when the school was operating without a physical presence and we were forced to respond to the ever changing conditions in NSW schools. Out of this extraordinary year emerged some remarkable achievements and a greater sense of appreciation of the value of friendship and collegiality which school life provides for us all. A landmark achievement was the construction of our long awaited building The Governors Centre with Sydney Boys High which throughout the months of the pandemic was able to be progressed with few interruptions to the building schedule. -

Sustaining Success: a Case Study of Effective Practices in Fairfield HVA

OCTOBER 2017 Sustaining Success: A case study of effective practices in Fairfield high value-add schools Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation The Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE), undertakes in-depth analysis of education programs and outcomes across early childhood, school, training and higher education to inform whole-of-government, evidence based decision making. Put simply, it seeks to find out what works best. CESE’s three main responsibilities are to: • provide data analysis, information and evaluation that improve effectiveness, efficiency and accountability of education programs and strategies. • collect essential education data and provide a one-stop shop for information needs – a single access point to education data that has appropriate safeguards to protect data confidentiality and integrity • build capacity across the whole education sector so that everyone can make better use of data and evidence. More information about the Centre can be found at: cese.nsw.gov.au Author Natalie Johnston-Anderson Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, October 2017, Sydney, NSW For more information about this report, please contact: Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation Department of Education GPO Box 33 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Email: [email protected] Telephone: +61 2 9561 1211 Web: cese.nsw.gov.au Acknowledgements The Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE) would like to sincerely thank the principals and teaching staff of the schools in this case study for generously sharing their time, perceptions and insights with the researchers. CESE also acknowledges the critical role of Fairfield Network Director, Cathy Brennan, in instigating this work and in celebrating the success of these schools. -

Independent Schools Scholarships & Bursaries2018

INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS SCHOLARSHIPS & BURSARIES 2018 Everything you need to know about scholarships and bursaries starts here IN THIS Why choose an independent education? ISSUE 6 helpful tips to make the most of your scholarship application experience PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS (select a school) All Saints College Redlands All Saints Grammar Roseville College Arden Anglican School Rouse Hill Anglican College Ascham School Santa Sabina College Blue Mountains Grammar School SCEGGS Darlinghurst Brigidine College - St Ives Sydney Church of England Frensham School Grammar School (Shore) Hills Grammar St Andrew’s Cathedral School Inaburra School St Catherine’s School - Waverley International Grammar School St Joseph’s College Kambala St Luke’s Grammar School Kinross Wolaroi School St Spyridon College Macarthur Anglican School Tara Anglican School For Girls MLC School The Armidale School (TAS) Monte Sant’ Angelo Mercy College The King’s School Newington College The McDonald College Our Lady of Mercy College Trinity Grammar School Presbyterian Ladies’ College Sydney Wenona School Ravenswood KAMBALA GIRLS SCHOOL ROSE BAY www.kambala.nsw.edu.au Kambala is an Anglican, independent day and boarding school for girls located on the rising shore above Rose Bay with a breathtaking view of Sydney Harbour. Founded in 1887, Kambala caters for students from Preparation to Year 12, with boarders generally entering the School from Year 7. Kambala offers a broad and holistic education and the opportunity for students to truly excel. Kambala’s rich and varied programs, administered in a positive and supportive environment, inspire every student to realise her own purpose with integrity, passion and generosity. Kambala aspires to raise leaders of the future who are academically curious and intellectually brave. -

Look up Reach out – Our Girls Creating a Better

TERM 1 - WEEK 4 ABBOTSLEIGH NEWSLETTER FEBRUARY 2019 IN THIS ISSUE The Headmistress Senior School Chaplain News Community Events Shuttle Junior School Time flies faster than a weaver’s shuttle. FROM THE HEADMISTRESS Look Up Reach Out – Our Girls Creating a Better Tomorrow, Today ’We have a great ability to bring JOY, much JOY, to the lives of others.’ Claire Luger, Vice Head Prefect – Service Mrs Megan Krimmer A wonderful and very special characteristic Christmas time, so that we could share with UPCOMING EVENTS for which our Abbotsleigh girls (and the them the joy of Christmas.’ whole Abbotsleigh community) are renowned, Monday 25 February In a powerfully empathic activity, Claire is their collective hearts for service and Junior School Camp Week invited the girls to ‘become’ one of the social justice. Following in the footsteps of commences 800,000 people living in Sydney who generations of Abbotsleigh girls, our girls are experienced the awful situation of facing a No AbbSchool or co-curricular extremely passionate about making a positive Christmas with little food and no presents events this week difference in our world: ‘creating a better last year. They and their ‘family’ then tomorrow, today’. Middle School Parent and ‘experienced’ the great joy of receiving toys Tutor Afternoon Tea Our Junior School girls enthusiastically and and a massive food hamper from Anglicare. generously support St Jude’s in Tanzania and We are sure that our girls will continue Tuesday 26 February sponsor World Vision children. They also visit to bring joy to others in Sydney as they Senior School Swimming aged care facilities and do fabulous work with implement the ‘Connect our Community’ Carnival the students at St Lucy’s School. -

HSC Outcomes 2020

2020 HSC Outcomes FROM THE PRINCIPAL AS OF 4PM, 18 DECEMBER 2020 ROSEVILLE COLLEGE Introduction 2020 Highlights The Higher School Certificate HSC Results (HSC) results released today • 4 students awarded All-Round Achievers for achieving are worthy of celebration – a the highest band possible in 10 or more units of study celebration of academic effort and success of our Year 12 class • 1st and 2nd in State for Food Technology of 2020, but more, they serve as • 4th and 9th in State for Personal Development, Health a resounding tribute to each girl and Physical Education (PDHPE) for her effort, determination and resilience in a year of unexpected • One student placed in the Top 25 in State for Science disruption and challenge. Extension The 2020 HSC results reflect • Five students placed in the Top 40 in Japanese Extension, outstanding achievement by French Extension, Ancient History and Design & graduates across all subject areas. Technology We celebrate the excellent results and the effort of every • 168 Band 6 or E4 results achieved by 76 students across student who has tried her very best. I am especially delighted 34 courses to announce that our students have received an incredible 268 pre-ATAR University Early Admission Offers. This continues • In 17 courses, Roseville College students achieved a strong trend for Roseville students and reflects the ability, upwards of 30% more Bands 5-6 than the state average character and service record of our girls – they are highly sought • Based on Band 6 and E4 achievements, Roseville College after. ranks 35th in NSW (SMH). To our Class of 2020, I warmly commended you. -

10 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10

Applications Years 8 – 11, 2022 Applications open Monday 21 June 2021 and close Friday 16 July 2021 All enquiries: Please email [email protected] Years 8 – 10 2022 All students applying for Fort Street High School must include the following with their application. 1. Completed Selective Schools Application Form available on the Selective High School website: https://education.nsw.gov.au/public-schools/selective-high-schools-and-opportunity-classes/years-8-to- 12 2. English writing piece of maximum 600 words (handwritten – not typed): Year 8 – 10 2022 Essay Topic (if you are in Year 7,8 or 9 in 2021) “Something good can come out of a crisis. A crisis can bring about a real change and help us re- evaluate our humanity”. (Discuss) 3. A copy of the student’s Birth Certificate or Passport 4. A copy of the Semester 2 - 2020 school report and Semester 1 – 2021 school report (if available) 5. Copies of evidence of recent participation in academic competitions and co-curricular activities 6. All applications must be posted and received before, on or date stamped Friday 16 July 2021. Please do not come to the school. No emailed applications. No late applications will be considered. Postal Address: Fort Street High School – Enrolments, Parramatta Road Petersham NSW 2049 7. There is no entrance test for applicants for Years 8 – 10, 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10 Applications There is a $50 non-refundable administration fee to cover the processing of the application. Payment can be made by cheque made out to Fort Street High School (to be included with the application) or on our school website: www.fortstreet.nsw.edu.au 1. -

Ascham Old Girls' Magazine

O N I N U ’ S L R I G D L O ASCHAM Ascham Old Girls’ Magazine Winter 2018 The Two of Us New York, Seeing my two daughters through New York Ascham fills me with gratitude for the How three Ascham In this issue education my parents Old Girls came to gave me and which work in the Big I totally took for Apple’s rag trade Ascham Old Girls’ granted at the time. 2 20 30 >> Full story p. 12 Magazine From our Patron In Conversation with Class of 1973— Winter 2018 Rowena Danziger AM 45 Year Reunion >> Full story p. 5 8 4 An artist, President’s Report 22 31 a sculptor and 100 Years of Tildesley Class of 1948— a curator 5 celebrated in style 70 Year Reunion The Two of Us 24 32 On the cover: Business Breakfast with Class of 2013— Harrie Fasher (1995) with her work 8 The Hon. Margaret Stone 5 Year Reunion Art at Ascham— Transition, winner of the Rio Tinto Major Award at Sculpture by the Sea An artist, a sculptor a historical perspective Cottesloe 2018. and a curator Photo: C Yee. Editorial team 26 33 Skye Barry (Edwards 1994), Gabrielle Class of 1957— Ascham Frensham Golf Day Bonney, Olivia Mallett (2010) 12 60 Year Reunion and APA Tennis Day Design 14 Scribble & Think New York, New York Layout Amelia Hull, Jennie Barrett 27 34 14 Class of 1967— Engagements, Marriages, Art at Ascham— 50 Year Reunion Births, Deaths a historical perspective 28 38 16 18 16 Class of 1977— Careers updates Visual Arts and Ascham Leadership Visual Arts and Design 40 Year Reunion and news Design Technology Scholarship Technology at Ascham now at Ascham now Winners 29 39 18 Class of 1968— Descendants of Ascham Leadership 50 Year Reunion Old Girls on the Scholarship Winners 2018 School Roll 20 26 In Conversation with Rowena Danziger AM Class of 1957 – 60 Year Reunion A S N C Editorial note O H I A N M U ’ This has been my first edition working as the editor of the Ascham Old Girls’ Magazine and S O L LD GIR I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it. -

IGSSA Cross Country Carnival Held at Frensham School Range

Association of Heads of Independent Girls’ Schools IGSSA Cross Country Carnival Held at Frensham School Range Rd, Mittagong Friday 17 May 2019 Walk the Course 8.30 am Races 9:30 am – 1:30 pm (These times are approximate) Risk Warning (Under Section 5M of Civil Liability Act 2002) On Behalf of AHIGS and participating AHIGS Member Schools listed below: Abbotsleigh Meriden School Ravenswood Ascham School MLC School Roseville College Brigidine College Monte Sant’ Angelo Santa Sabina College Canberra Girls Grammar Mount St Benedict SCEGGS Darlinghurst Danebank School New England Girls School Stella Maris College Frensham OLMC Parramatta St Catherine’s School Kambala PLC Armidale St Patrick's College Kincoppal-Rose Bay PLC Sydney St Vincent’s College Loreto Kirribilli Pymble Ladies’ College Tangara School Loreto Normanhurst Queenwood Tara Wenona Cross Country Carnival 2019 AHIGS and its members’ schools organises many individual and team sporting activities during the course of a year. Students participating in these sporting activities take part in practice and in competitions. AHIGS and its members’ schools expect students to take responsibility for their own safety by wearing compulsory safety equipment, by thinking carefully about the use of safety equipment that is highly recommended and by behaving in a safe and responsible manner towards team members, opponents, spectators, officials, property and grounds. AHIGS and its members’ schools also expect parents, spectators and other participants to behave in a safe and responsible manner, to comply with the IGSSA Code of Conduct and to set a good example for the girls. While AHIGS and its members’ schools take measures to make the Cross Country Carnival as safe as reasonably possible for participants, there is a risk that students can be injured and suffer loss (including financial loss) and damage as a result of their participation in these sporting activities, whether at training or in actual events. -

Schools Competition 2014 School Addresses and Contact Details

NSW Junior Chess League METROPOLITAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS COMPETITION 2014 SCHOOL ADDRESSES AND CONTACT DETAILS Abbotsleigh Region: Met North Address: 1666 Pacific Highway (cnr Ada Ave), Wahroonga NSW 2076 Chess Coordinator: Mr P Garside School Phone: 9473 7779 School Fax: 9473 7680 Ascham School Region: Met East Address: 188 New South Head Rd, Edgecliff NSW 2027 Chess Coordinator: Mr A Ferch School Phone: 8356 7000 School Fax: 8356 7230 Asquith Girls High School Region: Met North Address: Stokes Avenue, Asquith NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mr M Borri School Phone: 9477 6411 School Fax: 9482 2524 Australian International Academy - Sydney Campus Region: Met East Address: 420 Liverpool Road, Strathfield NSW 2135 Chess Coordinator: Mr W Zoabi School Phone: 9642 0104 School Fax: 9642 0106 Balgowlah Boys (Northern Beaches Secondary College - Balgowlah Boys Campus) Region: Met North Address: Maretimo Street, Balgowlah NSW 2093 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Hu School Phone: 9949 4200 School Fax: 9907 0266 Barker College Region: Met North Address: 91 Pacific Highway, Hornsby NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mrs G Cunningham School Phone: 9847 8399 School Fax: 9477 3556 Baulkham Hills High School Region: Met West Address: 419A Windsor Road, Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Chilwell School Phone: 9639 8699 School Fax: 9639 4999 Blue Mountains Grammar School Region: Met West Address: Matcham Avenue, Wentworth Falls NSW 2782 Chess Coordinator: Mr C Huxley School Phone: 4757 9000 School Fax: 4757 9092 Canterbury Boys High School Region: Met East Address: -

2018 Year 10 NSW State Da Vinci Decathlon Results

2018 NSW State da Vinci Decathlon Placings - Year 10 Overall Art & Poetry Cartography Creative Producers Engineering Rank School Rank School Rank School Rank School Rank School 1 Sydney Girls High School 1 Ravenswood 1 MLC School 1 Pittwater High School 1 St Augustine's College 2 Sydney Boys High School 2 Cammeraygal High School 2 Normanhurst Boys High School 2 Knox Grammar School 2 KamBala 3 Knox Grammar School 3 Sydney Girls High School 3 Knox Grammar School 3 Arndell Anglican School 3 Normanhurst Boys High School 4 North Sydney Girls High School 4 MLC School 4 ABBotsleigh 4 Cammeraygal High School 4 RoseBank College 5 Normanhurst Boys High School 5 Pittwater High School 5 North Sydney Girls High School 5 St Aloysius' College 5 Mount St Benedict College 5 Smith's High School 6 St Leo's Catholic College 6 Sydney Girls High School 6 KamBala 6 Bishop Tyrrell Anglican College 7 MLC School 7 ABBotsleigh 7 Sydney Boys High School 6 Loreto Kirribilli 7 Merici College 8 PymBle Ladies' College 8 Monte Sant' Angelo Mercy College 8 Monte Sant' Angelo Mercy College 6 St. George Girls High School 8 ABBotsleigh 9 Meriden School 9 Moriah College 9 St Luke's Grammar School 9 Smith's High School 9 Ravenswood 10 ABBotsleigh 10 North Sydney Girls High School 10 Meriden School 10 St.Patrick's College Strathfield 10 PymBle Ladies' College 11 St.Patrick's College Strathfield 11 KamBala 11 St.Patrick's College Strathfield 11 Trinity Grammar School 11 Roseville College 12 Cammeraygal High School 12 Penrith Anglican College 12 KamBala 12 CanBerra Grammar School -

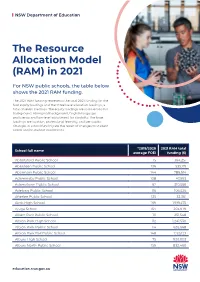

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public