Susanna Burghartz, Madeleine Herren, Hans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Finest and Most Complete Virtual Bell Instrument Available

Platinum Advanced eXperience by Chime Master The finest and most complete virtual bell instrument available. Front and center on the Platinum AX™ is a color touch screen presenting intuitive customizable menus. Initial setup screens clearly guide you with questions about your traditions, ringing preferences and schedule needs. The Platinum AX ™ features our completely remastered high definition Chime Master HD-Bells™. Choose your bell voice from twenty-five meticulously sampled authentic bell instruments including several chimes and carillons cast by European and historic American foundries. Powerful front facing speakers provide inside ringing and practice sound when you play or record the bells using a connected keyboard. Combined with a Chime Master inSpire outdoor audio system with full-range speakers, the reproduction of authentic cast bronze bells is often mistaken for a tower of real bells. An expansive library of selections includes thousands of hymns in various arrangements and multiple customizable ringing functions. You may expand your collection by personally recording or importing thousands more. Control your bells remotely from anywhere with Chime Master’s exclusive Chime Center™. This portal seam- lessly integrates online management and remote control. Online tools facilitate schedule changes, backup of recordings and settings, as well as automatic updates as soon as they are available! ® Where tradition meets innovation. ™ Virtual Bell Instrument FEATURES HD-Bells™ Built-In Powerful Monitor Speakers Twenty-five of the highest quality bell Exceptional monitoring of recording and instruments give your church a distinctive voice performances built right into the cabinet. in your community. Built-In Network Interface Enhanced SmartAlmanac™ Easy remote control via your existing smart Follows the almanac calendar and plays music phone or device. -

Carillon News No. 80

No. 80 NovemberCarillon 2008 News www.gcna.org Newsletter of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America Berkeley Opens Golden Arms to Features 2008 GCNA Congress GCNA Congress by Sue Bergren and Jenny King at Berkeley . 1 he University of California at TBerkeley, well known for its New Carillonneur distinguished faculty and academic Members . 4 programs, hosted the GCNA’s 66th Congress from June 10 through WCF Congress in June 13. As in 1988 and 1998, the 2008 Congress was held jointly Groningen . .. 5 with the Berkeley Carillon Festival, an event held every five years to Search for Improving honor the Class of 1928. Hosted by Carillons: Key Fall University Carillonist Jeff Davis, vs. Clapper Stroke . 7 the congress focused on the North American carillon and its music. The Class of 1928 Carillon Belgium, began as a chime of 12 Taylor bells. Summer 2008 . 8 In 1978, the original chime was enlarged to a 48-bell carillon by a Plus gift of 36 Paccard bells from the Class of 1928. In 1982, Evelyn and Jerry Chambers provided an additional gift to enlarge the instrument to a grand carillon of Calendar . 3 61 bells. The University of California at Berkeley, with Sather Tower and The Class of 1928 Installations, Carillon, provided a magnificent setting and instrument for the GCNA congress and Renovations, Berkeley festival. More than 100 participants gathered for artist and advancement recitals, Dedications . 11 general business meetings and scholarly presentations, opportunities to review and pur- chase music, and lots of food, drink, and camaraderie. Many participants were able to walk Overtones from their hotels to the campus, stopping on the way for a favorite cup of coffee. -

The Liberty Bell: a Symbol for “We the People” Teacher Guide with Lesson Plans

Independence National Historical National Park Service ParkPennsylvania U.S. Department of the Interior The Liberty Bell: A Symbol for “We the People” Teacher Guide with Lesson Plans Grades K – 12 A curriculum-based education program created by the Independence Park Institute at Independence National Historical Park www.independenceparkinstitute.com 1 The Liberty Bell: A Symbol for “We the People” This education program was made possible through a partnership between Independence National Historical Park and Eastern National, and through the generous support of the William Penn Foundation. Contributors Sandy Avender, Our Lady of Lords, 5th-8th grade Kathleen Bowski, St. Michael Archangel, 4th grade Kate Bradbury, Rydal (East) Elementary, 3rd grade Amy Cohen, J.R. Masterman, 7th & 10th grade Kim General, Toms River High School North, 9th-12th grade Joyce Huff, Enfield Elementary School, K-1st grade and Library Coach Barbara Jakubowski, Strawbridge School, PreK-3rd grade Joyce Maher, Bellmawr Park, 4th grade Leslie Matthews, Overbrook Education Center, 3rd grade Jennifer Migliaccio, Edison School, 5th grade JoAnne Osborn, St. Christopher, 1st-3rd grade Elaine Phipps, Linden Elementary School, 4th-6th grade Monica Quinlan-Dulude, West Deptford Middle School, 8th grade Jacqueline Schneck, General Washington Headquarts at Moland House, K-12th grade Donna Scott-Brown, Chester High School, 9th-12th grade Sandra Williams, George Brower PS 289, 1st-5th grade Judith Wrightson, St. Christopher, 3rd grade Editors Jill Beccaris-Pescatore, Green Woods -

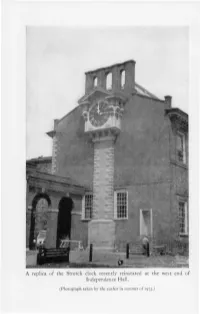

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

Vital Series, Mallets

USER MANUAL Produced by Vir2 Instruments 00 Vir2 Instruments is an international team of sound designers, musicians, and programmers who specialize in creating the world’s most advanced virtual instrument libraries. Vir2 is producing the instruments that shape the sound of modern music. 29033 Avenue Sherman, Suite 201 Valencia, CA 91355 Phone:661.295.0761 Web:www.vir2.com 00 MALLETS/ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 01: INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY 01 INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE CHAPTER 02: REQUIREMENTS AND INSTALLATION 02 SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS INSTALLING IN KONTAKT INSTALLING IN KOMPLETE KONTROL & MASCHINE AUTHORIZING UPDATING CHAPTER 03: USING KONTAKT 05 HOW TO ACCESS THE MALLETS LIBRARY FROM KONTAKT USING KONTAKT IN STANDALONE MODE USING KONTAKT WITH YOUR D.A.W. USING KONTAKT WITH ANOTHER HOST CHAPTER 04: GETTING STARTED WITH MALLETS 09 MALLETS OVERVIEW INSTRUMENT CONTROLS INSTRUMENTS TURNED ON VS INSTRUMENTS TURNED OFF GLOBAL FILTER TUNE ROLLS LFO CONTROLS EFFECTS TECHNICAL SUPPORT, ETC. 13 TECH SUPPORT FULL VERSION OF KONTAKT 5 LICENSE AGREEMENT CREDITS 14 CREDITS CHAPTER 01 01 02 MALLETS/ INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY Thank you for purchasing Mallets. / INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY / INTRODUCTION TO Vir2 Instruments is proud to present the first instrument in our Vital Series, Mallets. Mallets brings users a collection of highly detailed, mallet-based instruments, and places them all in an intuitive instrument for the Kontakt CHAPTER 01 Player. Offering multiple mallet types for the Marimba, Xylophone, Glockenspiel, Tubular Bells, Glass Marimba, Song Bells, Vibraphone, and Crotales, Mallets is extremely versatile. Furthermore, each of the aforementioned instruments are available within one single instance of the instrument, allowing for the layering of each instrument for the exploration of endless tonal color. -

About the Carillon

ABOUT THE CARILLON The carillon at Concordia Seminary is one of only 170 such instruments in North America. The 49 bells have been played atop Luther Tower since 1971, and are dedicated to all pastors who have served The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS). It is housed in Luther Tower, the 120- foot structure designed by architect Charles Klauder and dedicated in 1966. CONCORDIA SEMINARY, ST. LOUIS CARILLON CONCERT JUNE 26, 2018 7 P.M. KAREL KELDERMANS CARILLONNEUR Concordia Seminary 801 Seminary Place St. Louis, MO 63105 www.csl.edu 314-505-7000 PROGRAM BIOGRAPHY 1. Fugue Matthias van den Gheyn (1721-85) KAREL KELDERMANS is one of the pre-eminent carillonneurs in North arr. Karel Keldermans America. He has been the carillonneur for Concordia Seminary, St. Louis since 2000. He retired in 2012 from the position of full-time carillonneur 2. Leyenda Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) for the Springfield Park District in Springfield, Ill., where he also served as arr. Bert Gerken the director of the renowned International Carillon Festival for 36 years. 3. Suite Archaique Geo Clement (1902-69) He has given carillon concerts around the world for the past 40 years. He has released six solo carillon CDs and one of carillon and guitar duets Rigaudon, Pavane, Menuet with Belgian guitarist Wim Brioen. 4. Allegro Reijnold Popma van Oevering (1692-1781) For 12 years, along with his wife, Linda, he was co-owner of American arr. Karel Keldermans Carillon Music Editions, the largest publisher of new music for the carillon in the world. He was president of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North 5. -

Selective Analysis of 20Th Century Contemporary Percussion Ensembles Designated for Three Or More Players

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1968 Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players Raymond Francis Lindsey The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lindsey, Raymond Francis, "Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players" (1968). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3513. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SELECTIVE ANALYSIS OF 2 0 ^ CENTURY CONTEMPORARY PERCUSSION ENSEMBLES DESIGNATED FOR THREE OR MORE PLAYERS by Raymond Francis Lindsey B.M* University of Montana 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music University of Montana 1968 Approved by; L L u ' ! JP. 4 . Chairman, Board of Exami4/ers Deah/, Graduate School 1 :: iosa Date UMI Number: EP35093 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

SAVED by the BELL ! the RESURRECTION of the WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a Proposal by Factum Foundation & the United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust

SAVED BY THE BELL ! THE RESURRECTION OF THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a proposal by Factum Foundation & The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust Prepared by Skene Catling de la Peña June 2018 Robeson House, 10a Newton Road, London W2 5LS Plaques on the wall above the old blacksmith’s shop, honouring the lives of foundry workers over the centuries. Their bells still ring out through London. A final board now reads, “Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 1570-2017”. Memorial plaques in the Bell Foundry workshop honouring former workers. Cover: Whitechapel Bell Foundry Courtyard, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. Back Cover: Chains in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. CONTENTS Overview – Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 1 A Brief History of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel 9 2 The Whitechapel Bell Foundry – Summary of the Situation 11 3 The Partners: UKHBPT and Factum Foundation 12 3 . 1 The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust (UKHBPT) 12 3 . 2 Factum Foundation 13 4 A 21st Century Bell Foundry 15 4 .1 Scanning and Input Methods 19 4 . 2 Output Methods 19 4 . 3 Statements by Participating Foundrymen 21 4 . 3 . 1 Nigel Taylor of WBF – The Future of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 21 4 . 3 . 2 . Andrew Lacey – Centre for the Study of Historical Casting Techniques 23 4 . 4 Digital Restoration 25 4 . 5 Archive for Campanology 25 4 . 6 Projects for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 27 5 Architectural Approach 28 5 .1 Architectural Approach to the Resurrection of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel – Introduction 28 5 . 2 Architects – Practice Profiles: 29 Skene Catling de la Peña 29 Purcell Architects 30 5 . -

Size-Frequency Relation and Tonal System in a Set of Ancient Chinese Bells: Piao-Shi Bianzhong

J. Acoust.Soc. Jpn. (E)10, 5 (1989) Size-frequency relation and tonal system in a set of ancient Chinese bells: Piao-shi bianzhong Junji Takahashi MusicResearch Institute, Osaka College of Music, Meishin-guchi1-4-1, Toyonaka, Osaka, 561 Japan (Received5 April 1989) Resonancefrequencies and tonalsystem are investigatedon a setof ancientChinese bells named"Piao-shi bianzhong." According to the measurementof 12 bellspreserved in Kyoto,it is foundthat a simplerelation between frequency and sizeholds well. The relationtells frequency of a bellinversely proportional to squareof its linearmeasure. It is reasonableto concludethat the set wascast for a heptatonicscale which is very similarto F# majorin our days. Precedingstudies in historyand archaeologyon Piao- shi bellsare also shortlyreviewed. PACSnumber: 43. 75.Kk •Ò•à) in Kyoto. In ƒÌ ƒÌ 2 and 3, historical and 1. INTRODUCTION archaeological studies on the set will be reviewed. In China from 1100 B.C. or older times (Zhou In ƒÌ 6, musical intervals of the set will be examined and it will be discussed for what tonal system the period), bronze bells named "zhong" (•à) of special shape with almond-like cross section and downward bells were cast. mouth had been cast and played in ritual orchestra. 2. SHORT REVIEW ON After the excavation of a set of 64 zhong bells in 1978 PIAO—SHI BIANZHONG from the tomb or Marquis Yi of Zeng (˜ðŒò‰³), vigorous investigations have been concentrated upon In about 1928, many bronze wares including some zhong bells from many fields of researches as ar- zhong bells were excavated from tombs of Jincun chaeology, history, musicology, and, acoustics. -

Download a PDF of Our Community Brochure

Engagement with the communities of Oxford and Oxfordshire Did you know? St Giles’ Fair began as the parish feast of St Giles, first recorded in 1624. From the 1780s it became a toy fair, with general amusements for children. In the next century its focus shifted towards adults, with entertainment, rides and stalls. In the late 1800s there were calls for the fair to be stopped on the grounds that it encouraged rowdy behaviour. During Victorian times engineering advances brought the forerunners of today’s rides. Today the huge pieces of machinery fill St Giles’ with sparkling lights for a few days each year, and whizz within feet of ancient college buildings. The stone heads around the Sheldonian Theatre now number thirteen (there were originally fourteen, but one was removed to make way for the adjoining Clarendon Building.) It is not known what they were intended to represent – they might be gods, wise men, emperors or just boundary markers. The original heads were made by William Byrd and put up in 1669. Did you Replacements put up in 1868 were made in poor stone, know? which crumbled away; in 1972 the current set, carved by Michael Black of Oxford, were erected. More on page 4 STARGAZING AND SPIN-OUTS PAGE 1 Contents 2 Introduction from the Vice-Chancellor 3 Foreword from the Chair of the Community Engagement Group 5 Part 1: Part of the fabric of the city Part of the fabric 6 800 years of history of the 8 Economic impact city 9 Science Parks 1 0 Saïd Business School 11 Oxford University Press PART 1 PART 1 2 The built environment 13 -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

Beneath a Canvas of Green a Conductor's Analysis and Comprehensive Survey of Related Works for Percussion Ensemble and Winds B

i BENEATH A CANVAS OF GREEN A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS AND COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY OF RELATED WORKS FOR PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE AND WINDS BY TONYA PATRICE MITCHELL Submitted to the graduate degree program in the School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ____________________________________ Chairperson Paul W. Popiel ____________________________________ Matthew O. Smith ____________________________________ Sharon Toulouse ____________________________________ Forest Pierce ____________________________________ Martin Bergee Date Defended: April 18, 2018 ii The Lecture Recital Committee for TONYA P. MITCHELL certifies that this is the approved version of the following document: BENEATH A CANVAS OF GREEN A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS AND COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY OF RELATED WORKS FOR PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE AND WINDS ____________________________________ Chairperson Paul W. Popiel Date Approved: April 18, 2018 iii ABSTRACT This document functions as an examination of Aaron Perrine’s (1979) Beneath a Canvas of Green (2018), a work for percussion ensemble and wind band. Included in this paper are sections outlining the composer’s background, the conception and commissioning process of the piece, a conductor’s analysis, rehearsal considerations, final thoughts regarding the necessity of new commissions and their impact on the development of band repertoire, as well as a historical overview of the percussion ensemble and list of similar works for this medium. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Aaron Perrine for collaborating with me on the production of this beautiful composition. I’d also like to thank Michael Compitello for assisting with the percussion design and set-up. I thank the members of the University of Kansas Wind Ensemble for enacting our vision.