Inaugural Lecture Exploring Sailortown Civic Culture, Slums and Scandal In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepney Consultation: Salmon Lane Area

Stepney Consultation: Salmon Lane Area Tower Hamlets is committed to making the borough a safer place which people can take pride in. We are looking to deliver a range of improvements to our streets for everyone’s benefit, whether you walk, cycle, use public transport or drive. The first area to be reviewed is Stepney as we have received funding through Transport for London and development contributions to improve the area. “This is an exciting opportunity to improve the streets of Stepney. There are lots of small changes we could make which would really improve the streets in this area and discourage dangerous driving. We want to know your ideas – where do you think a small change would make a big improvement? We’ve put forward some of our ideas but we know it is local residents who know their streets best. So share your ideas and together we can Transform Stepney and make it an even better place to live. We’re rolling out improvements in the Stepney area first of all, but other areas throughout the borough will follow soon.” - the Mayor The Transforming Stepney’s Streets improvement area is framed by the A13, Sidney Street, A11, and Mile End Park and has approximately 9,500 residential homes. We are planning to make a range of improvements to the area, to help create better connected walking and cycling routes (including to the many schools in the area), making our roads safer and reducing the volume of traffic using these roads as a ‘rat run’. We also want to improve the look and feel of the area, making it an even more enjoyable, and safer, place to live, work and visit. -

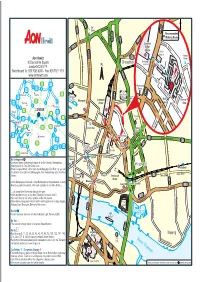

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Leamouth Leam

ROADS CLOSED SATURDAY 05:00 - 21:00 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00TO WER 4 2- 12:30 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 14:00 3 3 ROUTE MAP ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 A1 LEA A1 LEA THE GHERR KI NATCLIFF RATCLIFF RATCLIFF CANNING MOUTH R SATURDAY 4th AUGUST 05:00 – 21:00 MOUTH R SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 05:00 – 14:00 LIMEHOUSE WEST BECKTON AD AD BANK OF WHITECHAPEL BECKTON DOCK RO SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 14:00 – 18:00 TOWN OREGANO DRIVE OREGANO DRIVE CANNING LLOYDS BUILDING SOUTH ST PAUL S ENGL AND Limehouse DLR SEE MAP CUSTOM HOUSE EAST INDIA O EAST INDIA DOCK RO O ROYAL OPER A AD AD CATHED R AL LEAMOUTH DLR PARK OHO LIMEHOUSE LIMEHOUSBecktonE Park Y Y HOUSE Cannon Street Custom House DLR Prince Regent DLR Cyprus DLR Gallions Reach DLR BROMLEY RIGHT A A ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 Royal Victoria DLR W W Mansion House COVENT Temple Blackfriars POPLAR DLR DLR Tower Gateway LE A MOUTH OCEA OCEA Monument COMMERC COMMERC V V GARDEN IAL ROAD East India RO UNDABOU T IAL ROAD ExCEL UNIVERSI T Y ROYAL ALBERT SIL SIL ITETIONAL CHASOPMERSETEL Tower Hill Blackwall DLR OF EAST LONDON SEE MAP BELOW RT R AIT HOUSE MILLENIUM ROUNDABOUT DLR Poplar E TOWN GALLE RY BRIDGE A13 VENU A13 VENUE SAFFRON A SAFFRON A SOUTHWARK THE TO WER Westferry DLR DLR BLACKWALL Embankment ROTHERHITH E THE MUSEUM AD AD CLEOPATRA’S BRIDGE OF LONDON EAST INDIA DOCK RO EAST INDIA DOCK RO LONDON WAPPING T UNNEL OF LONDON West India A13 A13 LEAMOUTH NEED LE SHADWELL LONDON CI T Y BRIDGE DOCK L A NDS Quay BILLINGSGATE AIRPOR T A13 K WEST INDIA DOCK RD K WEST INDIA DOCK RD LEA IN M ARKET IN LEAM RATCLIFF L L SE SE MOUT WAY TATE MODERN HMS BELFAST U U SPEN O O AD A N H H A AY A N W E TOWER E E 1 ASPEN 1 H R W E G IM IM 2 2 L L OREGANO DRIVE 0 W 0 OWER LEA CROSSING L CANNING P LOWER LEA CROSSIN BRIDGE 6 O 6 O EAST INDIA DOCK RO POR AD R THE O2 BL ACK WAL L Y T LIMEHOUSE PR ESTO NS A T A A C C HORSE SOUTHWARK W V RO AD T UNNEL O O E V T T . -

Restoring the 'Mam'

Restoring the ‘Mam’: Archives, Access and Research into Women’s Pasts in Wales MANDI O’NEILL The history of Welsh people has often been camouflaged in British history yet women have been rendered inconspicuous within their own Welsh history.1 t has been suggested that ‘Welsh women are culturally invisible’2 in a country which has had a predominantly male workforce in its modern history which resulted in a strong cultural identity around I 3 rugby and male voice choirs which excluded women. Welsh women were strongly identified with the domestic sphere and have been represented as a sort of nostalgic, idealised mother: the ‘mam’, the matriarch of the home, waging a constant battle, often in the face of economic deprivation, to keep her home and family clean and well-fed, often at the expense of her own health. ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness’, Public History Review Vol 18 (2011): 47–64 © UTSePress and the author Public History Review | O’Neill could have been her mantra: her reputation – which was all-important – was one of hard work, thrift and piety. Rarely, if ever, working outside the home, social activities revolved around the chapel. Pubs and politics were for the men.4 Government statistics have tended to reinforce the somewhat homogenous, domestic view of Welsh women. In the mid interwar period, only twenty-one percent of women in Wales were recorded as economically active5 although oral history interviews reveal that women did take on additional work, often in the home, to supplement family income.6 While the idealised ‘mam’ is rooted firmly in the coalmining communities of the South Wales Valleys, there were plenty of women in urban areas such as Cardiff and Swansea and large parts of rural Wales who did not conform to this image. -

Limehouse Trail 2017

Trail The lost east end Discover London’s first port, first Chinatown and notorious docklands Time: 2 hours Distance: 3 ½ miles Landscape: urban The East End starts where the City of London finishes, Location: east of the Tower. A short walk from this tourist hub Shadwell, Wapping and Limehouse, leads to places that are much less visited. London E1W and E14 Some of the names are famous: Cable Street, where Start: locals held back the fascist blackshirts; or Limehouse, Tower Gateway DLR Station or where Britain’s first Chinese population gained mythical Tower Hill Underground Station status. Finish: Some are less known, such as Wellclose Square, a Westferry DLR Station Scandinavian square with an occult reputation, and Ratcliff, where ships set sale to explore the New World. Grid reference: TQ 30147 83158 These parts of London were once notorious, home to Keep an eye out for: sailors from across the globe and reputed to be wild and lawless. Now they hold clues to their past, which can be The Old Rose pub at the top of Chigwell Hill, decoded by retracing their borders beside the Thames. a real slice of the lost East End Directions From Tower Hill - avoid the underpass and turn left outside the station to reach Minories, and cross to Shorter Street. From Tower Gateway - take the escalators to street level, turn left on to Minories then left again along Shorter Street. From Shorter Street - Cross Mansell Street and walk along Royal Mint Street. Continue along the street for a few minutes, passing the Artful Dodger pub, then crossing John Fisher Street and Dock Street. -

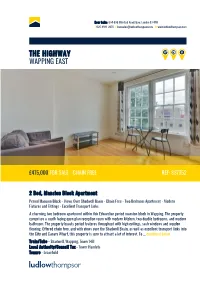

The Highway Wapping East

Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com THE HIGHWAY WAPPING EAST £475,000 FOR SALE - CHAIN FREE REF: 837352 2 Bed, Mansion Block Apartment Period Mansion Block - Views Over Shadwell Basin - Chain Free - Two Bedroom Apartment - Modern Fixtures and Fittings - Excellent Transport Links A charming two bedroom apartment within this Edwardian period mansion block in Wapping. The property comprises a south facing open plan reception room with modern kitchen, two double bedrooms, and modern bathroom. The property boasts period features throughout with high ceilings, sash windows and wooden flooring. Offered chain free, and with views over the Shadwell Basin, as well as excellent transport links into the City and Canary Wharf, this property is sure to attract a lot of interest. To ... continued below Train/Tube - Shadwell, Wapping, Tower Hill Local Authority/Council Tax - Tower Hamlets Tenure - Leasehold Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com THE HIGHWAY WAPPING EAST Reception (Open Plan) Kitchen Bathroom Bedroom 1 Bedroom 2 View From Reception Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com THE HIGHWAY WAPPING EAST Entrance Exterior Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com THE HIGHWAY WAPPING EAST Please note that this floor plan is produced for illustration and identification purposes only. -

Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements

Cycle Superhighway 3 Upgrade Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements Response to Consultation March 2015 Cycle Superhighway 3 Upgrade Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements Response to Consultation Published March 2015 Executive summary Between 30 January and 27 February 2015, Transport for London (TfL) consulted on road safety improvements to Cable Street as part of an upgrade to Cycle Superhighway 3. We received 90 direct responses to the consultation, 76 (or 85%) of which supported or partially supported our proposals. After considering all responses, we have decided to proceed with the scheme incorporating the following additional measures to those originally proposed: Reviewing the signal timings at the junction of Cable Street and Cannon Street to maximise the green time available for cyclists Replacing the speed cushion with a sinusoidal hump at the junction of Cable Street and Hardinge Street Extending double yellow lines around junctions but not across the cycle track Subject to final discussions with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is the highway authority responsible for Cable Street, we expect work to start in summer 2015. We will write to local residents and affected properties before work starts to provide a summary of this consultation, an overview of the updated proposals and an outline of the construction programme. This document explains the processes, responses and outcomes of the recent consultation, and sets out our response to issues commonly raised. Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... -

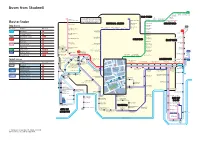

Buses from Shadwell from Buses

Buses from Shadwell 339 Cathall Leytonstone High Road Road Grove Green Road Leytonstone OLD FORD Stratford The yellow tinted area includes every East Village 135 Old Street D3 Hackney Queen Elizabeth Moorfields Eye Hospital bus stop up to about one-and-a-half London Chest Hospital Fish Island Wick Olympic Park Stratford City Bus Station miles from Shadwell. Main stops are for Stratford shown in the white area outside. Route finder Old Ford Road Tredegar Road Old Street BETHNAL GREEN Peel Grove STRATFORD Day buses Roman Road Old Ford Road Ford Road N15 Bethnal Green Road Bethnal Green Road York Hall continues to Bus route Towards Bus stops Great Eastern Street Pollard Row Wilmot Street Bethnal Green Roman Road Romford Ravey Street Grove Road Vallance Road 115 15 Blackwall _ Weavers Fields Grove Road East Ham St Barnabas Church White Horse Great Eastern Street Trafalgar Square ^ Curtain Road Grove Road Arbery Road 100 Elephant & Castle [ c Vallance Road East Ham Fakruddin Street Grove Road Newham Town Hall Shoreditch High Street Lichfield Road 115 Aldgate ^ MILE END EAST HAM East Ham _ Mile End Bishopsgate Upton Park Primrose Street Vallance Road Mile End Road Boleyn 135 Crossharbour _ Old Montague Street Regents Canal Liverpool Street Harford Street Old Street ^ Wormwood Street Liverpool Street Bishopsgate Ernest Street Plaistow Greengate 339 Leytonstone ] ` a Royal London Hospital Harford Street Bishopsgate for Whitechapel Dongola Road N551 Camomile Street 115 Aldgate East Bethnal Green Z [ d Dukes Place continues to D3 Whitechapel Canning -

Museum of London Docklands-October 2019

Grumpy Old Men’s Club update The October outing for the Grumpies on Wednesday 30th was an interesting visit to the Museum of London Docklands. The museum, which is situated in Limehouse and is close to Canary Wharf, tells the history of London's River Thames and the growth of Docklands. From Roman settlement to Docklands’ regeneration, the museum unlocks the history of London’s river, port and people in this historic warehouse. It displays a wealth of objects from whale bones to WWII gas masks in state-of-the-art galleries, including Sailortown, an atmospheric re-creation of 19th century riverside Wapping; and London, Sugar & Slavery, which reveals the city’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Trade expansion from 1600 to 1800 tells the story of how ships sailed from London to India and China and brought back cargoes of spices, tea and silk. The museum’s building is central to this story. It was built at the time of the transatlantic slave trade, to store the sugar from the West Indian plantations where enslaved men, women and children worked. The trade in enslaved Africans and sugar was nicknamed the Triangular Trade. Slave ships travelled across the Atlantic in a triangle between Britain, west Africa, and sugar plantations in the Americas. Vast fortunes were made from this triangle. By the mid-18th century there were so many ships in the port of London that their cargoes often rotted before they could be unloaded. The West India Docks were built to prevent this long wait for space at the quayside. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES SAINT PAUL, SHADWELL: the HIGHWAY, TOWER HAMLETS P93/PAU3 Page 1 Reference Description Dates Parish

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 SAINT PAUL, SHADWELL: THE HIGHWAY, TOWER HAMLETS P93/PAU3 Reference Description Dates Parish Records P93/PAU3/001 Composite register: baptisms, marriages and 1670-1698 Not available for general access burials Please use microfilm Baptisms Mar 1670/1 - Jun 1711 (most entries X092/063 include abode, father's occupation, and age at Please use microfilm baptism); Marriages Mar 1671 - Oct 1698 (from May 1674 entries include parish and from Aug 1695 abode and occupation); Burials Mar 1670/1 - Feb 1679/80 (entries include abode and occupation) P93/PAU3/002 Register of baptisms Jul 1712-Mar Unfit Gives abode, father's occupation and age at 1736/7 Not available for general access baptism Please use microfilm X024/128 Please use microfilm P93/PAU3/003 Register of baptisms Mar 1737-Dec Not available for general access Gives abode, father's occupation and age at 1774 Please use microfilm baptism X024/128 Please use microfilm P93/PAU3/004 Register of baptisms Jan 1775-Dec Not available for general access Gives abode, father's occupation and age at 1809 Please use microfilm baptism. Entries 1806-9 are arranged X024/128 alphabetically in index section at end of volume. Please use microfilm Includes P93/PAU3/004/02: Sworn statement by John Nicholson that he was present at the baptism of Elizabeth Harrison Nichols P93/PAU3/005 Register of baptisms including contemporary Jan 1810-Dec Not available for general access index 1812 Please use microfilm Gives abode, father's occupation and age at X024/128 baptism Please use microfilm P93/PAU3/006 Register of baptisms Jan 1813-Dec Not available for general access Gives alleged dates of birth. -

The Place of Sailors in Port Cities, Through the Example of 19Th Century Le Havre by Dr

The place of sailors in port cities, through the example of 19th century Le Havre by Dr. Nicolas Cochard, University of Caen A recent article by Robert Lee, lamenting the lack of attention paid to the study of sailors on land, invites us to reflect on the aims of the historical studies devoted to seafarers. According to Lee, the “deconstruction” of the common perception of sailors, maintained by literature, is yet to be perfected. Our knowledge of the integration of sailors into society at times of great technological change remains limited and clichés sometimes prevail. Through examples of British and Scandinavian spaces, Lee states that the study of sailors offers great historical perspectives, evoking in turn the pre-established links between sailors, alcohol, prostitution, and violence as well as the preconceptions relating to irresponsibility, the innate and definitive attachment of a sailor to the sea and his frequentation of urban spaces restricted to the quays. In his opinion, in order to understand the maritime populations subject to the influence of the technological evolutions of the 19th century, research into families, social networks, the place of women and new cultural sensitivities and customs is needed1. Lee invites us to construct a history of sailors that reassesses our existing knowledge, taking account of this particular context. Concerning the French coasts in the late modern period, the theme of the integration of sailors into society remains little explored to date. On the whole, the history of sailors is still “under construction”2, particularly regarding commercial sailors in the late modern period. In fact, certain major works of French historiography have made it possible to lay the foundations for research into the life of sailors on land, but the early modern period largely dominates. -

The White Chapel Building Has Been Innovatively Refurbished Into a 21St Century Hub for Creative Businesses, Exuding Integrity and Attention to Detail

Contents The Building 7 The Atrium 10 The Terrace & Braham Park 17 The Space 19 Key Features 22 Stacking Plan 26 Floor Plans 27 The Location 33 Transport 34 Elizabeth Line 37 Regeneration 38 Derwent London 43 Contact 44 2 The Building The White Chapel Building has been innovatively refurbished into a 21st century hub for creative businesses, exuding integrity and attention to detail. At street level, the new impressive steel clad entrance portal and bold, eye-catching lettering over the door provides a welcoming arrival. Thanks to the Elizabeth Line and a huge upsurge of local investment, planning, infrastructure and talent, Whitechapel is ideally positioned to become a destination for the next wave of east London innovation. 7 The Atrium The doors open into an impressive 7,000 sq ft ground-floor atrium. The heart of The White Chapel Building acts as a focal point and destination for tenants, visitors and the wider community. Different zones within this vast, multifunctional space fulfill different purposes. Housing a stylish and modern reception area, multiple breakout and meeting spaces, workstations, hangouts and a buzzing café/bar run by Grind, creating a sense of warmth and community for the entire building. The White Chapel Building is not only a vibrant workspace, it is a place to relax, enjoy and invite friends. 10 11 12 13 14 15 The Terrace & Braham Park The atrium leads out to a landscaped terrace with café seating and direct links to Braham Park. The new environment is warm and welcoming and as one of the capital’s newest green spaces, this is likely to become Whitechapel’s best kept secret.