TEXAS COURTHOUSES DESIGNED by OSCAR RUFFINI by LORRAINE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Bexar County Courthouse by Sylvia Ann Santos

The History Of The Bexar County Courthouse By Sylvia Ann Santos An Occasional Publication In Regional History Under The Editorial Direction Of Felix D. Almaraz, Jr., The University Of Texas At San Antonio, For The Bexar County Historical Commission Dedicated To The People Of Bexar County EDITOR'S PREFACE The concept of a history of the Bexar County Courthouse originated in discussion sessions of the Bexar County Historical Commission. As a topic worthy of serious research, the concept fell within the purview of the History Appreciation Committee in the fall semester of 1976. Upon returning to The University of Texas at San Antonio from a research mission to Mexico City, I offered a graduate seminar in State and Local History in which Sylvia Ann Santos accepted the assignment of investigating and writing a survey history of the Bexar County Courthouse. Cognizant of the inherent difficulties in the research aspect, Mrs. Santos succeeded in compiling a bibliography of primary sources and in drafting a satisfactory outline and an initial draft of the manuscript. Following the conclusion of the seminar, Mrs. Santos continued the pursuit of elusive answers to perplexing questions. Periodically in Commission meetings, the status of the project came up for discussion, the usual response being that sound historical writing required time for proper perspective. Finally, in the fall of 1978, after endless hours of painstaking research in old public records, private collections, and microfilm editions of newspapers, Mrs. Santos submitted the manuscript for editorial review and revision. This volume is a contribution to the Bexar County Historical Commission's series of Occasional Publications in Regional History. -

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek by Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek By Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes [Note: The images reproduced in this internal report are all in the public domain, but the originals remain the intellectual property of their respective owners. None may be reproduced in any way using any media without the specific written permission of the owner. The authors of this report will be happy to help facilitate acquiring such permission.] Native Americans living along San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River 10,000 years ago were sustained by the swiftly flowing waterways that nourished a rich array of vegetation and wildlife. This virtual oasis in an arid landscape became a stopping place for Spanish expeditions that explored the area in the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was here that Governor Domingo Terán de los Ríos, accompanied by soldiers and priests, camped under cottonwood, oak, and mulberry trees in June 1691. Because it was the feast of Saint Anthony de Padua, they named the place San Antonio.1 In April 1709 an expedition led by Captain Pedro de Aguirre, including Franciscan missionaries Fray Isidro Félix de Espinosa and Fray Antonio Buenventura Olivares, visited here on the way to East Texas to determine the possibility of establishing new missions there. On April 13 Espinosa, the expedition’s diarist, wrote about a lush valley with a plentiful spring. “We named it Agua de San Pedro.” Nearby was a large Indian settlement and a dense growth of pecan, cottonwood, cedar elm, and mulberry trees. Espinosa recorded, “The river, which is formed by this spring, could supply not only a village, but a city, which could easily be founded here.”2 When Captain Domingo Ramón visited the area in 1716, he also recommended that a settlement be established here, and within two years Viceroy Marqués de Valero directed Governor Don Martín de Alarcón to found a town on the river. -

San Antonio San Antonio, Texas

What’s ® The Cultural Landscape Foundation ™ Out There connecting people to places tclf.org San Antonio San Antonio, Texas Welcome to What’s Out There San Antonio, San Pedro Springs Park, among the oldest public parks in organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation the country, and the works of Dionicio Rodriguez, prolificfaux (TCLF) in collaboration with the City of San Antonio bois sculptor, further illuminate the city’s unique landscape legacy. Historic districts such as La Villita and King William Parks & Recreation and a committee of local speak to San Antonio’s immigrant past, while the East Side experts, with generous support from national and Cemeteries and Ellis Alley Enclave highlight its significant local partners. African American heritage. This guidebook provides photographs and details of 36 This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s digital What’s Out examples of the city's incredible landscape legacy. Its There San Antonio Guide (tclf.org/san-antonio), an interactive publication is timed to coincide with the celebration of San online platform that includes the enclosed essays plus many Antonio's Tricentennial and with What’s Out There Weekend others, as well as overarching narratives, maps, historic San Antonio, November 10-11, 2018, a weekend of free, photographs, and biographical profiles. The guide is one of expert-led tours. several online compendia of urban landscapes, dovetailing with TCLF’s web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s most From the establishment of the San Antonio missions in the comprehensive searchable database of historic designed st eighteenth century, to the 21 -century Mission and Museum landscapes. -

ARLIS/NA Texas-Mexico Chapter Fall Meeting October 18-20, 2019

ARLIS/NA Texas-Mexico Chapter Fall Meeting October 18-20, 2019 Houston, TX Research Roundtable Visual Literacy Is Information Literacy: Active Learning Helps Students Teach Themselves to Evaluate Images and Their Sources Shari Salisbury, Reference Librarian / Subject Specialist for Art & Art History, The University of Texas at San Antonio Students in art and art history are often asked by professors to use an image of an artwork in an assignment. In art history this may be for the purpose of formal analysis and research on its art historical context. In studio arts this may be for the purpose of inspiration or to use as an example to copy style or technique for their own art project. Some professors report that students are not careful to find good, representative art reproductions when given such an assignment. Working with art faculty teaching Drawing I at the University of Texas at San Antonio, the art librarian developed an active learning activity that aligns with standard four of the ACRL Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, “The visually literate student evaluates images and their sources” and the first frame of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education, “Authority is Constructed and Contextual.” Using prompts provided by the librarian in class, students teach themselves through individual investigation and group discussion that evaluating images also means evaluating their sources, which is foundational not only for visual literacy, but also for information literacy. Using Photos as Data: How Students Speak through the Camera Lens to Identify Space Needs Tina Budzise-Weaver, Associate Professor and Humanities and Social Sciences Librarian, Texas A&M University Tina Budzise-Weaver, Pauline Melgoza, Dr. -

The English Texans

Texans One and All The English Texans Texans of English origin seem A Walk Across Texas to be the least colony-minded Perhaps the first English in Texas were David Ingram, Rich- people in the state. One rea- ard Twide, and Richard Browne, seamen who were put son is that the English are part ashore on the Mexican coast in 1568 by Captain John Haw- of the “Anglo” majority that kins. Hawkins, in league with the future Sir Francis Drake, has formed Texas since the had lost a disastrous naval battle with the Spanish. mid-1830s. English settlers are The survivors of the sunken ships, crowded onto Hawkins’ often invisible. remaining Minion, elected not to perish by starvation on a Some of the early English were doubtful return to England, but to be set ashore. Walking not so invisible to the Spanish. south, they could at least find the comforts of a Spanish prison. John Hamilton visited the mouth of the Trinity River as a Once ashore, three seaman decided to walk north. This horse buyer about 1774 and they apparently did, turning east across Texas’ coastal plain to enjoy an eventual Atlantic rescue by a French ship. English architect Alfred Giles (c. purchased stolen livestock...an 1875), designer of many buildings activity not overly welcomed David Ingram wrote a short account of the journey which around Texas and Mexico by the Spanish. Yet in 1792, appeared in print in 1589, a fairly accurate description of the Gulf of Mexico coastal areas. “The Countrey is good,” John Culbert, a silversmith, was allowed to live in San Antonio. -

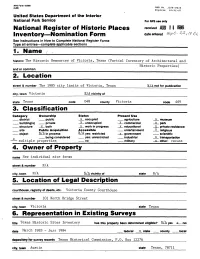

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1. Name

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received AUG I I Inventory Nomination Form date entered [ri <5( See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections__________________________ 1. Name ________________________ historic The Historic Resources of Victoria, Texas (Partial Inventory of Architectural and Historic Properties) and or common____________________•__________________________ 2. Location street & number The 1985 city limits of Victoria, Texas N/A not for publication city, town Victoria N/A vicinity of state Texas code 048 county Victoria code 469 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture x museum building(s) private x unoccupied x commercial x park structure x both X work in progress x educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object N/A in process N/A yes: restricted x government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted __ industrial x transportation multiple properties __ "no military x other: vacant 4. Owner off Property name See individual site forms street & number N/A city, town N/A I/A vicinity of state N/A 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Victoria County Courthouse street & number 101 North Bridge Street city, town Victoria state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Texas Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? N/A yes z_ no date March 1983 - June 1984 federal x state county local depository for survey records Texas Historical Commission, P.O. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS FEBRUARY 1973 VOL. XVII NO . 1 PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Alan Gowans, President • Editor: James C. Massey, 614 S. Lee Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Assoc. Ed.: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Conn. Ave., N.W. , Washington, D.C. 20008 • Asst. Ed.: Elisabeth Walton, 765 Winter St., N.E. Salem, Oregon 97301 SAHNOTICES SAH Annual Business Meeting. The Society's annual business 1973 Annual Meeting-Foreign Tour, Cambridge University meeting was held in New York on January 27, during the and London (August 15-27). The Pan American charter flight College Art Association convention. As announced, the SAH is filled, and registrations for the flight and the meeting-tour annual meeting will be held in Cambridge and London in are now closed. August. The following officers were elected: President, Alan Gowans (University of Victoria); First Vice-President, Spiro K. 1974 Annual Meeting, New Orleans (April 3-7). Spiro K. Kostof (University of California, Berkeley); Second Vice Kostof, First Vice-President, is General Chairman for the President, Marian C. Donnelly (University of Oregon); Secre meeting; Bernard Lemann and Samuel Wilson, Jr. are Local tary, Elisabeth MacDougall (Dumbarton Oaks- Harvard Uni Co-Chairmen. (SAH meets alone.) Persons interested in pre versity); and Treasurer, Robert W. Jorgensen (Peifer and senting papers should write Professor Kostof (7733 Claremont Associates, Inc. , Chicago). Seven new directors were elected at Avenue, Berkeley, Calif. 94705). the meeting: Abbott L. Cummings (Society for the Preserva 1975 Annual Meeting, Boston (April 23-27). -

Architectural Ancestors Sixty-Sixty Place Texas Capitol Architect Main Street Spanish FAIA: Three from Texas Architect Plus Regular Columns

In this issue: Our Architectural Ancestors Sixty-Sixty Place Texas Capitol Architect Main Street Spanish FAIA: Three from Texas Architect Plus regular columns. See Contents. NUMBER 3 VOL 24 JULY/AUGUST 1974 Contents Editorial . 3 Official hbllcalloa of 1lle Texas Soclely of A rc:llltecu Our Architectural Ancestors ... 5 TSA •• the offiaal or1an1ut1on or the Tuai Rc11on of the A re specrf11I and humorow, Uffmmt ofsome of Amcncan lni111utc of Ardutcct> Texas· more prominent 19th century co11r1ho11se De, T&)loc • • • • • • • • • • •••••••••• EJ11or-1n-Ch1cf archi1ec1s-inc/11ding one 11 hose stafi{ecoach L&il) Paul Fuller ..•.••••.•....•. Managina Editor Ray Rtta . • • . • • . • . • .. • . • . A1soc111c Editor 1,as rCJbbed as he tral'eled w a job site. hmn 0 . Pfluacr, AJA • • • . Ednori&I Co~uhan1 Bobbie Yauger . • • . .•..•....••. Edi1onal AUl\lant Sixty-Sixty Place .... .. .. 1 O ~ ltor lal Polley Co• •III« tl,,rr) (inlcnwn, Chairman Capitol Architect ... .. ..... 12 Mar\ln l:lc,lanJ l nm Mnriarily The Texas Swre cap,rol b11ildinl(, 1,·ide(v Gcorsc l."""8 Jim l'llugcr Jin, Mc)Cr Joe S..n1umur11 praised 11po11 its a1mple1im1 i11 /888, wa.1 llm•11rJ l'Jrkcr Charles Sluhl des1vied b) a Dt•troir an h,rert named EliJah E. The TfXA'> AkC lfl II CT h puhhmed ,,. 11010 Myers, 1,/w share,/ in 11,1111• of the J,000,000 )CUI) h) the I cu• Soc,el) nl Arch11ec11, 1100 l'Crr) aae.t of Te.w.1 mnch 11111,I U1n1rded 10 the llrooh llu1ldrng, 121 I u.1 11th Suec1, Au,un, lo.. co111n1ctor.1. 78701 Suhscriptlun price u J4 00 per )OI ,n •d· ,uncc, fur addrcuc, "'nhm 1he cnn11nental lfn11ed Century Center . -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS DECEMBER 1982 VOL. XXVI NO. 6 SAH NOTICES tour. There we will visit outstanding buildings, museums, 1983 Annual Meeting-Phoenix, Arizona (April 6-10). Carol adjacent towns, and crafts workrooms and factories. The H. Krinsky, New York University, is serving as general itinerary includes Turku with its medieval and m ulti-cul chairman of the meeting. Bernard Michael Boyle, Arizona tural heritage, the sites where the works of Saarinen, Aalto, State University and Robert C. Giebner, University of Sonck, and other architectural leaders are located, towns on Arizona-Tucson, are working on the meeting as local the coasts and inland, and workshops for furniture, ceram chairmen. Headquarters for the meeting will be the Phoenix ics, glass, and fabrics. We will meet Finnish historians, Hilton Hotel. The Preliminary Program will be sent to all architects, curators, and preservationists. members early in January. Members abroad who wish to The tour will use first class hotels, not much more costly at have the program sent airmail should notify the SAH office that season than budget hotels and large enough to handle as soon as possible. groups. Our arrangements are being made by an intelligent Finnish-born travel agent, who is married to an architect, and who has contacts of her own to assist us. She will be able 1984 Annual Meeting-Minneapolis, Minnesota (April 25- to arrange optional pre- or post-tour individual travel, e.g., 29). General chairman of the 1984 meeting will be Carol H. to the U.S.S.R. or Scandinavia. Krinsky, of New York University. -

Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas

Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas —A Biographical Dictionary Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas ii Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas —A Biographical Dictionary Frank Wilson Kiel Skyline Ranch Press Comfort, Texas 2013 iii Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas Copyright © 2013 Frank Wilson Kiel All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. First edition Skyline Ranch Press 133 Skyline Drive Comfort, Texas 78013 [email protected] Kiel, Frank Wilson 1930– Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas—A Biographical Dictionary vi 205 pp., including 10 tables. Bibliography, 183 references. 1. Civil War soldiers. 2. Kendall County, Texas. 920 CT93.K54 2013 Library of Congress Control Number 2013918956 ISBN 978–0–9834160–1–2 iv Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas Contents Preface Historiography……………………………………….2 Geography…………………………………………...3 Demography…………………………………………5 The Affair at the Nueces………………………….....6 Joining the Confederate forces………………………8 Letters and Pension Applications…………………..10 Methodology…………………………………….....10 Reconciliation…………………………………….. 17 Soldiers in military units………………………………….21 Tables 1. Sources………………………………………..153 2. Naturalizations………………………………..164 3. Eligible men and their units…………………..167 4. Losses………………………………................170 5. Wounded………………………………...……171 6. Prisoners………………………………...…….173 7. Unit affiliation………………………………...175 8. Death, Obituary, and Cemetery……………… 177 9. Tombstone inscriptions………………………. 192 10. Last soldiers and widows……………………...194 Bibliography………………………………...…………....195 v Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas vi Civil War Soldiers of Kendall County, Texas Preface Small towns in the Hill Country of Texas, such as Comfort and Boerne, have a reputation as strongholds of Union support in the Civil War. Comfort’s Treue der Union monument commemorates this heritage. -

An English Architect in Kendall County Alfred Giles, Architect (1853-1920) Part I by Myrna Flach Langford

7 An English Architect in Kendall County Alfred Giles, Architect (1853-1920) Part I By Myrna Flach Langford By appearance and reputation it would seem, at first glance anyway, that it was an easy life for architect Alfred Giles. Should you meet him in late 1800s perhaps on a street in Comfort near the Faltin building or in Boerne near the old Kendall County Courthouse, where he would later oversee its new façade design and expansion, he would seem a privileged gentleman of means and talent. You most certainly would have heard of his reputation for the fine architecture of countless Texas courthouses, military facilities, and San Anto- nio’s King William area mansions, as well as his large homestead, Hillingdon Ranch in Kendall County. An easy life? Discounting of course, the unease of leaving his saddened rela- tives in England, the heartbreaking experiences of losing three of his children to the ravages of the times, and the office fire destroying his papers. Of course too there was the harrowing stagecoach robbery, the turmoil of legal proceedings against him in El Paso, the frequent trips to building sites with inadequate communication and new workers and materials to oversee… were surely a hassle. Architect Alfred Giles Also there was the unfruitful, wasted time involved with unused drawings of the Alamo cenotaphs and others (See Spring 2020 Echoes, Kendall County Connection Our visit to Hillingdon, England to Alamo Plaza - Alfred Giles’ Vision for Early Revitalization Efforts). A bit of strife with our daughter and two for certain; frustrations that required the persistent tenacity and even nature of grandchildren in 2015 revealed this creative man. -

Wise County Courthouse- the Preservation Ofthe Essence of the Perfect Building

WISE COUNTY COURTHOUSE- THE PRESERVATION OFTHE ESSENCE OF THE PERFECT BUILDING by JAMES ODELL TATE ATHESIS IN ARCHITECTURE Submitted to the Architecture Faculty of the College of Architecture of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of BAØHELOR 9PSAR(piflJTECTURE 'Chairmain-© -me/îQmmittQe Programming Instructor (ARCH-4000): Willard B. Robinson Design Critic (ARCH-4631): Dr. R.A.A. Petrini di Monforte Accepted / .--•---—-—-^.i- — • DearafCollege of Architecture Mí^th^ Year III w iiætioMw ©@[tJi^TO@a Architects should not be made the convenience of contractors. -HENRY HOBSON RICHARDSON- WISE COUNTY COURTHOUSE iraiba^ ©lî ©(£)[{^ií@cn)ií^ Title Page iii Preface V Table of Contents vii List of lllustrations ix Introduction 1 History 5 1. County of Wise 5 II. City of Decatur 7 III. James Riely Gordon 9 IV. Courthouse History 13 Goals-Objectives 17 Environmental Analysis 23 Site Analysis 30 Courthouse Environmental Quality 37 User Analysis 43 Space Parimeters 51 Economlc Feasibility 59 Implementation and Initial Detailed Costs Analysis 61 Case Studies 69 1. Henry Hobson Richardson 69 II. San Antonio Museum 71 III. Marshall County Courthouse 73 IV. Henderson Mansion 75 V. Chenago County Courthouse 77 Appendixes 80 A. Courthouse History 81 B. Photo-Documentation 90 C. Design Standards 92 D. Courthouse Guidelines 96 E. Checklist for Court Facilities Design 102 F. A Selected Bibliography 111 VII \Lm ©H Oaa[y]^ii raii3®o^^ Figures: Page 1. Wise County 4 2. Decatur 6 3. James Railey Gordon 8 4. Denton County Courthouse (1895), Architects' Drawing 10 5. Wise County Courthouse (1895-1897), Architects' Drawing 12 6.