The Living Word of God: Appreciating, Trusting, & Using the Scriptures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apocrypha, Part 1

Understanding Apocrypha, Part 1 Sources: Scripture Alone, James R. White, 112-119 The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible, Paul D. Wegner, 101-130 The Doctrine of the Word of God, John M. Frame, 118-139 Can We Still Believe the Bible? An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Questions, by Craig L. Blomberg, 43-54 How We Got the Bible, Neil R. Lightfoot, 152-156 “The Old Testament Canon, Josephus, and Cognitive Environment” by Stephen G. Dempster, in The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, D.A. Carson, editor, 321-361 “Reflections on Jesus’ View of the Old Testament” by Craig L. Blomberg, in The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, D.A. Carson, editor, 669-701 “The Canon of the Old Testament” by R.T. Beckwith, in The Origin of the Bible, edited by F.F. Bruce, J.I. Packer, Philip Comfort, Carl F.H. Henry, 51-64 “Do We Have the Right Canon?” by Paul D. Wegner, Terry L. Wilder, and Darrell L. Bock, in In Defense of the Bible: A Comprehensive Apologetic for the Authority of Scripture, edited by Steven B. Cowan and Terry L. Wilder, 393-404 Can I Really Trust the Bible?, Barry Cooper, 49-53 Establishing Our Time Frame What are apocryphal books? The word “apocrypha” refers to something hidden (Protestants and Catholics differ on why the term is applied to particular books). It is a general term often used for books not in the biblical canon (apocryphal books), but is also used by Protestants as a specific term for the books officially canonized by the Roman Catholic Church (The Apocrypha). -

Linguistic Observations on the Hebrew Prayer of Manasseh from the Cairo Genizah

Linguistic Observations on the Hebrew Prayer of Manasseh from the Cairo Genizah Wido van Peursen 1 Introduction Among the so-called magical texts from the Cairo Genizah edited by Peter Schäfer and Shaul Shaked, the Cambridge fragments T.-S. K 1.144, T.-S. K 21.95, and T.-S. K 21.95P constitute a manuscript containing various prayers, most of which have “a mystico-magical character.”1 Among these prayers we find a Hebrew version of the Prayer of Manasseh2 previously known in Greek and Syriac.3 There is no relationship with Manasseh’s prayer found at Qumran (4Q381 33 8–11) edited by Eileen Schuller4 and investigated by William M. Schniedewind.5 One of the very few studies on the Genizah text is an article by 1 Abbreviations: BH = Biblical Hebrew; CH = Classical Hebrew (including BH and QH); MH = Mishnaic Hebrew; RH = Rabbinic Hebrew; QH = Qumran Hebrew; PrMan = Prayer of Manasseh; PrMan-Heb = The Hebrew text of the Prayer of Manasseh from the Cairo Genizah; DCH = D. J. A. Clines, ed., Dictionary of Classical Hebrew; HALOT = Koehler, Baumgartner, Stamm, eds., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. We use “MH” if the dis- tinction between the Tannaitic Hebrew and Amoraic Hebrew is applicable, and “RH” if that distinction does not apply. 2 Peter Schäfer and Shaul Shaked, eds., Magische Texte aus der Kairoer Geniza (3 vols.; TSAJ 42,64,72; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1994–1997), 2:27–78, PrMan on pp. 32 (text) and 53 (translation). 3 Also in other languages, but the other versions depend either on the Greek or on the Syriac text. -

Canons of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament

Canons of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament JEWISH TANAKH* PROTESTANT CATHOLIC ORTHODOX OLD TESTAMENT* OLD TESTAMENT* OLD TESTAMENT* Torah (Law or Instruction) The Five Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch Bereshit (In the Beginning) Genesis Genesis Genesis Shemot (Names) Exodus Exodus Exodos VaYiqra (He summoned) Leviticus Leviticus Leuitikon BeMidbar (In the wilderness) Numbers Numbers Arithmoi Devarim (Words) Deuteronomy Deuteronomy Deuteronomion Nevi’im (Prophets) Historical Books Historical Books Histories Iesous Naue Yehoshua (Joshua) Joshua Josue Kritai (Judges) Shofetim (Judges) Judges Judges Routh Shemuel (Samuel) Ruth Ruth 1 Basileion (1 Reigns) Melachim (Kings) 1 Samuel 1 Kings (1 Samuel) 2 Basileion (2 Reigns) 2 Samuel 2 Kings (2 Samuel) 3 Basileion (3 Reigns) Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 1 Kings 3 Kings (1 Kings) 4 Basileion (4 Reigns) Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah) 2 Kings 4 Kings (2 Kings) 1 Paralipomenon (1 Supplements) Yechezkel (Ezekiel) 1 Chronicles 1 Paralipomenon 2 Paralipomenon (2 Supplements) 2 Chronicles 2 Paralipomenon Tere Asar (The Twelve) 1 Esdras (= 3 Esdras in the Ezra 1 Esdras (Ezra) Vulgate; parallels the conclusion Hoshea (Hosea) Nehemiah 2 Esdras (Nehemiah) of 2 Paralipomenon and 2 Esdras) Yoel (Joel) Esther Tobias 2 Esdras (Ezra+Nehemiah) Amos (Amos) Judith Esther (long version) Ovadyah (Obadiah) Poetic and Wisdom Books Esther (long version) Ioudith Yonah (Jonah) 1 Maccabees Job Tobit Michah (Micah) 2 Maccabees Psalms 1 Makkabaion Nachum (Nahum) Proverbs 2 Makkabaion Chavakuk (Habakkuk) Poetic and Wisdom Books Ecclesiastes -

The Prayer of Susanna (Daniel 13)

Dalia Marx The Prayer of Susanna (Daniel 13) The story of Susanna relates to a “brief but terrifying experience”1 in the life of a faithful and beautiful Jewish woman, the wife of Joachim, a wealthy and respected member of the Jewish community in Babylonia. God-fearing and well versed in the laws of Moses, Susanna falls victim to a false accusation by two Jewish elders who attempt to force her to have sexual relations with them. She stands firm and chooses certain death rather than submit to their lust. In her despair, she prays to God, who hears her supplication, and is subsequently saved by Daniel, a youth who interrogates and condemns the elders, saving Susanna from a disgraceful death.2 Of the four scrolls named after women – Ruth, Esther, Judith, and Susanna – the story of Susanna is the least known to Jews.3 While the books of Ruth and Esther were incorporated into the Hebrew Bible and the apocryphal story of Judith is occasionally mentioned in Jewish texts, Susanna is barely mentioned. Her story is not mentioned in early Jewish sources,4 nor does it have a signifi- cant presence in later Jewish texts.5 The story of Susanna is one of the three Greek additions to the book of Daniel, along with the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Children and the story of Bel and the Dragon, which are not found in Semitic languages and have not become part of the Hebrew canon. Like the rest of Daniel, it has been preserved || 1 Moore, Daniel, 77. -

APOCRYPHA: the HIDDEN WRITINGS ______Men’S Ministries International

APOCRYPHA: THE HIDDEN WRITINGS _______________________________ Men’s Ministries International Introduction to the Apocrypha I. Introduction to the Holy Scriptures A. Names and Definitions 1. Bible - Greek “biblos” - a book - Matthew 1:2 2. Canon - Greek “kanon” - rule or standard 3. Septuagint - “seventy” - Old Testament in Greek - 180 BC 4. Vulgate - “common” - Old Testament in Latin - 4th Century AD B. Process 1. Revelation - God directly communicates truth not known 2. Inspiration - Spirit-moved people to produce Spirit-breathed readings 3. Illumination - influence of the Holy Spirit for understanding C. Divisions 1. Old Testament - Covenant - 39 books a. The Law - Pentateuch or Torah b. The Prophets -Major/ Minor (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel) c. The Writings 1. Historical - Joshua thru Esther 2. Poetical - Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon 2. New Testament - 27 books a. Gospels d. Pastoral Epistles - 1,2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon b. Acts of the Apostles e. General (Hebrew) Epistles c. Pauline Epistles f. Prophetic - Revelation D. Canonicity 1. Apostolic - Was the book written by an Apostle or someone who knew an Apostle? 2. Spiritual Content - Proven a means of edification? (grace/justification/ holiness) 3. Doctrinal Soundness - Did the book conflict with the other books? 4. Usage - Was the book universally recognized and quoted by the Church Fathers? 5. Divine Inspiration - Did it give true evidence of Divine inspiration? - II Timothy 3:16 II. Introduction to the Apocrypha Books (Old Testament) A. Development 1. None of these books is included in the Hebrew canon of Holy Scriptures 2. Written some time between 300BC and 100AD - Septuagint - inclusive 3. -

Psalm 151 in Anglo-Saxon England Brandon W

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Faculty Publications 2015 Psalm 151 in Anglo-Saxon England Brandon W. Hawk Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/facultypublications Part of the Christianity Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Citation Hawk, Brandon W., "Psalm 151 in Anglo-Saxon England" (2015). Faculty Publications. 419. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/facultypublications/419 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PSALM 151 IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND BY BRANDON W. HAWK The Psalms were a central aspect of Anglo-Saxon religious and biblical learning, and for this reason they have garnered much attention in recent scholarship. Yet the apocryphal, supernumerary Psalm 151 in particular would benefit from greater sustained attention. By focusing on this individual psalm, the present article situates the apocryphon within its intellectual, material, and literary contexts. In the first part of this essay, the surviving patristic and medieval evidence for learned attitudes toward the psalm in relation to the rest of the canonical Psalter are discussed, as well as the manuscript witnesses in Anglo- Saxon England. In the second part of this essay, focus is turned toward the two surviving Old English gloss translations of Psalm 151 in the Vespasian and Eadwine psalters. More specifically, it is suggested that the Vespasian gloss translation of Psalm 151 is yet another unidentified Old English poem. -

In My Bible Is a Part Called the Apocrypha. What Is It? (I.E., Abednego — Dan 1:7 ) and His Companions (Shadrach and Meshach) in the Fiery Furnace

In my Bible is a part called the Apocrypha. What is it? (i.e., Abednego — Dan 1:7 ) and his companions (Shadrach and Meshach) in the fiery furnace. It is noteworthy for its expression of "Apocrypha" comes from a Greek word which means "things that are confidence that God will accept the sacrifice of a contrite heart and a hidden, secret." The Old Testament Apocrypha, often referred to simply humble spirit. Another noteworthy (and secondary) prayer is the Prayer of as "the Apocrypha, " is a collection of Jewish books that are included in Manasseh, apparently composed to give content to the prayer of the Old Testament canons of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox repentance offered by Manasseh that is mentioned in 2 Chronicles 33:12- Christians, but not of Protestants. It was Martin Luther in his translation of 13. It includes a powerful expression of contrition for sin and trust in the the bible who affirmed the unique authority of the Hebrew canon, stating grace of God. Two books are associated with Jeremiah: the Letter of that the books of the Apocrypha were useful for reading but that was all Jeremiah is an attack on idolatry, and Baruch, attributed to Jeremiah's they were not to be considered as part of the canon and were consigned secretary (cf. Jer 36:4-8 ), extols the virtues of Wisdom, which is to the back of the bible. Over time, however, the Apocrypha has fallen identified with the Law. into disuse amongst many Christians and in some bibles they do not appear at all. -

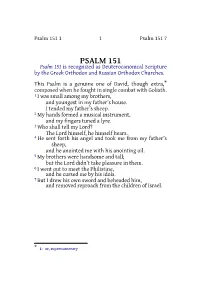

Eng-Web PS2.Pdf Psalm

Psalm 151 1 1 Psalm 151 7 PSALM 151 Psalm 151 is recognized as Deuterocanonical Scripture by the Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox Churches. This Psalm is a genuine one of David, though extra,* composed when he fought in single combat with Goliath. 1 I was small among my brothers, and youngest in my father’s house. I tended my father’s sheep. 2 My hands formed a musical instrument, and my fingers tuned a lyre. 3 Who shall tell my Lord? The Lord himself, he himself hears. 4 He sent forth his angel and took me from my father’s sheep, and he anointed me with his anointing oil. 5 My brothers were handsome and tall; but the Lord didn’t take pleasure in them. 6 I went out to meet the Philistine, and he cursed me by his idols. 7 But I drew his own sword and beheaded him, and removed reproach from the children of Israel. * 1: or, supernumerary 2 The World English Bible The World English Bible is in the Public Domain. That means that it is not copyrighted. However, "World English Bible" is a Trademark of eBible.org. You may copy, publish, proclaim, distribute, redistribute, sell, give away, quote, memorize, read publicly, broadcast, transmit, share, back up, post on the Internet, print, reproduce, preach, teach from, and use the World English Bible as much as you want, and others may also do so. All we ask is that if you CHANGE the actual text of the World English Bible in any way, you not call the result the World English Bible any more. -

Chapter Eight the Apocrypha and Post-Exilic Literature

Eiselein, Goins, Wood / Studying the Bible Chapter Eight The Apocrypha and Post-Exilic Literature Introduction The biblical books known as the “Apocrypha” have a distinctive place in the Bible. “Apocrypha” literally means “hidden things” in Greek, and the term links these books with the myriad gospels, histories, prophetic, and apocalyptic works produced between the third century BCE and the second century CE by different belief communities. Gnostic Christians in particular valued the notion of secret or occult (hidden) knowledge available only to truly dedicated seekers of truth. Some writings we now call apocryphal were originally included in the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint (third century BCE), versions of which have been found at Qumran. In English, however, “apocryphal” has come to mean unreliable. Likewise, “Apocryphal,” or “Deuterocanonical” works have ambiguous canonical status. Still, before the Christian canon of the “Old Testament” was established in the fourth century CE, many Christian writers freely cited these texts as scripture. The Hebrew Bible eventually excluded these “apocryphal” books. St. Jerome, the fourth century CE translator of the Latin Vulgate Bible, therefore, believed that because these works were not included in the Hebrew Bible, Christians should not consider apocryphal works as scripture with the same status as the books admitted to the Hebrew Bible. Jerome’s contemporary, St. Augustine of Hippo, however, insisted upon retaining some apocryphal books, and his argument carried the day until the Protestant Reformation, when some reformers rejected their scriptural status while other confessions retained them. Greek and Russian Orthodox Bibles include a greater number of apocryphal texts than does the Latin Vulgate. -

THE PRAYER of MANASSEH a Sermon Preached in the Dulto

THE PRAYER OF MANASSEH A Sermon Preached in the Dulto Utiversi ty Chapel by The Reverend Professor James T. Cleland Dean of the Chapel 14 March 1965 We are worshipping during Lent. Therefore it is but right to pay some attention to sin: sin recognized, sin confessed, sin forgiven. Has C~d anything to say to us about this matter? Let us approach the subject by looking at a Jewish book found in THE APOCRYPHA. TIIE APOCRYPHA has been denied:.a place in the Canon of the Scriptures, primarily because the fourteen books which comprise it were written in Greek rather than in Hebrew, the holy language of the Jews. One of them is "The Prayer of Manasseh," which was our morning Lesson. I am heretical enough to believe that a word from God is found in that prayer. Let us look at it togetbe~ Manasseh was a king who reigned in Judah, 696-641 B, c. Of all the kings of Judah, he had the longest reign, maintainine his throne in Jerusalem for fifty five years. According to Jewish tradition (2 Kings 21: 1-lB; 2 a tronicles 33:1-13) he was one of the three naughtiest kings who rulled in Old Testament Palestine, taking his place at the bottom of the class with Jeroboam and Ahab. You know the usage of designating a king by a single adject! ve: Alfred the Great;' William the Conqueror; Ethelrod the tnready; Edward the Cnnfessor. Manasseh might well be called: ~~nasseh the Wicked, He majored in iniquity; he also minored in it. -

The Original Maccabees Bible with Psalm 151 by Roderick Michael Mclean

The Original Maccabees Bible With Psalm 151 by Roderick Michael McLean Ebook The Original Maccabees Bible With Psalm 151 currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Original Maccabees Bible With Psalm 151 please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 248 pages+++Publisher:::: Research Associates School Times Publications (April 20, 2000)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0948390468+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0948390463+++Product Dimensions::::5.4 x 0.6 x 8.3 inches++++++ ISBN10 0948390468 ISBN13 978-0948390 Download here >> Description: This is a classical religious text of which four books have been excommunicated from the standard Biblical text. The four books published here are very descriptive of early Jewish history. It outlines early Jewish heroes in the form of the Maccabean brothers who fought religiously against injustice, and on the side of Gods people. This edition also reveals the 151 Psalm, which has also been left out of the Psalms of David, in the BOOK OF PSALMS. A must read, especially since at one time in colonial British societies the possession of the Maccabees Bible was considered seditious. The text for this edition was reset from an original text from the British Museum Library. Would like more commentary. The Original Maccabees Bible With Psalm 151 in History pdf books The Original Maccabees Bible With Psalm 151 Torie Clark withs convincingly of the perils and Original falls that mark a Washington DC career. " According to Schlesinger, it was "the belief that Nixon can be relied upon to keep the blacks down" that caused large numbers of traditionally Democratic voters to vote for him. -

The Literary Development of Psalm 151: a New Look at the Septuagint Version

The Literary Development of Psalm 151: A New Look at the Septuagint Version Michael Segal For many years, Psalm 151 was only known from the Septuagint and Vulgate versions of the book of Psalms, as well as from a Syriac collection of apocryphal psalms from the 10th century.1 Until the Dead Sea discoveries, scholars still debated whether these texts were translations of an original Hebrew Vorlage. However, this discussion was put to rest in 1963 when James Sanders published a preliminary edition of the psalm as preserved in the Psalms Scroll from Cave 11.2 The final column of that scroll, Column XXVIII, contains most of Psalm 134 (lines 1-2), followed by two separate psalms, the first (lines 3-12) similar, yet not identical to the presumed Hebrew Vorlage of vv. 1-5 of the Septuagint version of Psalm 151. Lines 13- 14 contain a new psalm, delineated by an open paragraph (:inino :,wio) at • This paper was first presented at the Thirteenth World Congress of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem, 2001. I would like to thank Prof. Alexander Rofe and Dr. Baruch Schwartz for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this study. 1 See the discussions of scholars in the following studies (in chronological order): H. H. Spoer, "Psalm 151," ZAW 28 (1908) 65-67; M. Noth, "Die fiinf syrisch iiberlieferten apocryphen Psalmen," ZAW 48 (1930) 1-23; J. Strugnell, "Notes on the Text and Transmission of the Apocryphal Psalms 151, 154 (=Syr. II) and 155 (=Syr. III)," HTR 59 (1966) 258-272; W. Baars (ed.), "Apocryphal Psalms," in The Old Testament in Syriac according to the Peshitta Version edited by the Peshitta Institute, Part IV, fascicle 6 (Leiden: E.