Management of Laryngeal and Tracheal Blunt Trauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larynx Anatomy

LARYNX ANATOMY Elena Rizzo Riera R1 ORL HUSE INTRODUCTION v Odd and median organ v Infrahyoid region v Phonation, swallowing and breathing v Triangular pyramid v Postero- superior base àpharynx and hyoid bone v Bottom point àupper orifice of the trachea INTRODUCTION C4-C6 Tongue – trachea In women it is somewhat higher than in men. Male Female Length 44mm 36mm Transverse diameter 43mm 41mm Anteroposterior diameter 36mm 26mm SKELETAL STRUCTURE Framework: 11 cartilages linked by joints and fibroelastic structures 3 odd-and median cartilages: the thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis cartilages. 4 pair cartilages: corniculate cartilages of Santorini, the cuneiform cartilages of Wrisberg, the posterior sesamoid cartilages and arytenoid cartilages. Intrinsic and extrinsic muscles THYROID CARTILAGE Shield shaped cartilage Right and left vertical laminaà laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple) M:90º F: 120º Children: intrathyroid cartilage THYROID CARTILAGE Outer surface à oblique line Inner surface Superior border à superior thyroid notch Inferior border à inferior thyroid notch Superior horns à lateral thyrohyoid ligaments Inferior horns à cricothyroid articulation THYROID CARTILAGE The oblique line gives attachement to the following muscles: ¡ Thyrohyoid muscle ¡ Sternothyroid muscle ¡ Inferior constrictor muscle Ligaments attached to the thyroid cartilage ¡ Thyroepiglottic lig ¡ Vestibular lig ¡ Vocal lig CRICOID CARTILAGE Complete signet ring Anterior arch and posterior lamina Ridge and depressions Cricothyroid articulation -

How the Larynx (Voice Box) Works

How the Larynx (Voice Box) Works Charles R. Larson, PhD If you love opera, or if you admire the voices of pop singers such as Celine Dion or Barbra Streisand, you may have wondered how it is these marvelous singers are able to create such beautiful music with this instrument we call the human voice. You may also know of someone who has a bad voice or has had to have their voice box, or larynx, removed because of illness or injury. The larynx is a critical organ of human speech and singing, and it serves important biological functions as well. Let's have a look at the larynx to understand its functions, what it looks like and how it works. It is thought that the same factors that favored the evolution of air‐breathing animals on earth led to the evolution of the larynx. Lungs are comprised of very delicate tissues that must be maintained within strict biological limits, that is, temperature, humidity and freedom from foreign particles. Thus, along with the first air‐breathing animals, there appeared a primitive sort of larynx, whose one and only function was protection of the lung. This function remains the most important of those the larynx has assumed in subsequent evolutionary developments. Now, of course we recognize that the larynx is critical for human speech and singing. But we also should realize that the larynx is important for swallowing, coughing, vomiting and eliminating contents of the abdomen. If you have ever felt your 'Adam's Apple', then you know where the larynx is. -

Cricoid Pressure: Ritual Or Effective Measure?

R eview A rticle Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9) 620 Cricoid pressure: ritual or effective measure? Nivan Loganathan1, MB BCh BAO, Eugene Hern Choon Liu1, MD, FRCA ABSTRACT Cricoid pressure has been long used by clinicians to reduce the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation. Historically, it is defined by Sellick as temporary occlusion of the upper end of the oesophagus by backward pressure of the cricoid cartilage against the bodies of the cervical vertebrae. The clinical relevance of cricoid pressure has been questioned despite its regular use in clinical practice. In this review, we address some of the controversies related to the use of cricoid pressure. Keywords: cricoid pressure, regurgitation Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9): 620–622 INTRODUCTION imaging showed that in 49% of patients in whom cricoid Cricoid pressure is a technique used worldwide to reduce pressure was applied, the oesophageal position was lateral to the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation in sedated or the cricoid ring.(5) As oesophageal occlusion was thought to be anaesthetised patients. Cricoid pressure can be traced back to crucial, this study challenged the efficacy of cricoid pressure. the late 18th century when it was used to prevent gas inflation More recently, in magnetic resonance imaging studies, Rice et of the stomach during resuscitation from drowning.(1) Sellick al showed that cricoid pressure causes compression of the post- noted that cricoid pressure could both prevent regurgitation cricoid hypopharynx rather than the oesophagus itself. -

Interaction Between the Thyroarytenoid and Lateral Cricoarytenoid

Interaction Between the Thyroarytenoid and Lateral Cricoarytenoid Jun Yin1 Muscles in the Control Speech Production Laboratory, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, of Vocal Fold Adduction University of California, Los Angeles, 31-24 Rehabilitation Center, 1000 Veteran Avenue, and Eigenfrequencies Los Angeles, CA 90095-1794 2 Although it is known vocal fold adduction is achieved through laryngeal muscle activa- Zhaoyan Zhang tion, it is still unclear how interaction between individual laryngeal muscle activations Speech Production Laboratory, affects vocal fold adduction and vocal fold stiffness, both of which are important factors Department of Head and Neck Surgery, determining vocal fold vibration and the resulting voice quality. In this study, a three- University of California, Los Angeles, dimensional (3D) finite element model was developed to investigate vocal fold adduction 31-24 Rehabilitation Center, and changes in vocal fold eigenfrequencies due to the interaction between the lateral cri- 1000 Veteran Avenue, coarytenoid (LCA) and thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles. The results showed that LCA con- Los Angeles, CA 90095-1794 traction led to a medial and downward rocking motion of the arytenoid cartilage in the e-mail: [email protected] coronal plane about the long axis of the cricoid cartilage facet, which adducted the pos- terior portion of the glottis but had little influence on vocal fold eigenfrequencies. In con- trast, TA activation caused a medial rotation of the vocal folds toward the glottal midline, resulting in adduction of the anterior portion of the glottis and significant increase in vocal fold eigenfrequencies. This vocal fold-stiffening effect of TA activation also reduced the posterior adductory effect of LCA activation. -

The Cricoid Cartilage and the Esophagus Are Not Aligned in Close to Half of Adult Patients

CARDIOTHORACIC ANESTHESIA, RESPIRATION AND AIRWAY 503 The cricoid cartilage and the esophagus are not aligned in close to half of adult patients [Le cartilage cricoïde et l’œsophage ne sont pas alignés chez près de la moitié des adultes] Kevin J. Smith MD,* Shayne Ladak MD,† Peter T.-L. Choi MD FRCPC,* Julian Dobranowski MD FRCPC† Purpose: To determine the frequency and degree of lateral dis- de 3,3 mm ± 1,3 mm d’écart type par rapport à la ligne médiane du placement of the esophagus relative to the cricoid cartilage cricoïde. Soixante-quatre pour cent des déplacements latéraux de (“cricoid”) using computed tomography (CT) images of normal l’œsophage allaient au delà du bord latéral du cricoïde (moyenne de necks. 3,2 mm ± 1,2 mm d’écart type). Nous avons noté une distribution Methods: Fifty-one cervical CT scans of clinically normal patients relativement normale des mesures groupées de pourcentage de were reviewed retrospectively. Esophageal diameter, distance diamètre œsophagien déplacés. De ces déplacements, 48 % présen- between the midline of the cricoid and the midline of the esopha- taient plus de 15 % de la largeur totale de l’œsophage déplacé gus, and distance between the lateral border of the cricoid and the latéralement et 20 % avaient plus de 20 % de déplacement. lateral border of the esophagus were measured. Conclusion : La fréquence de déplacement latéral de l’œsophage Results: Lateral esophageal displacement was observed in 49% d’un certain degré par rapport au cricoïde est de 49 %. (25/51) of CT images. When present, the mean length of displaced esophagus relative to the midline of the cricoid was 3.3 mm ± SD 1.3 mm. -

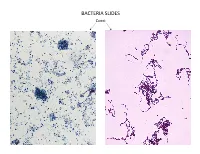

Bacteria Slides

BACTERIA SLIDES Cocci Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES _______________ __ BACTERIA SLIDES Spirilla BACTERIA SLIDES ___________________ _____ BACTERIA SLIDES Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES ________________ _ LUNG SLIDE Bronchiole Lumen Alveolar Sac Alveoli Alveolar Duct LUNG SLIDE SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL Superior Concha Auditory Tube Middle Concha Opening Inferior Concha Nasal Cavity Internal Nare External Nare Hard Palate Pharyngeal Oral Cavity Tonsils Tongue Nasopharynx Soft Palate Oropharynx Uvula Laryngopharynx Palatine Tonsils Lingual Tonsils Epiglottis False Vocal Cords True Vocal Cords Esophagus Thyroid Cartilage Trachea Cricoid Cartilage SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View Hyoid Bone Superior Horn Thyroid Cartilage Inferior Horn Thyroid Gland Cricoid Cartilage Trachea Tracheal Rings LARYNX MODEL Posterior View Epiglottis Hyoid Bone Vocal Cords Epiglottis Corniculate Cartilage Arytenoid Cartilage Cricoid Cartilage Thyroid Gland Parathyroid Glands LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View ____________ _ ____________ _______ ______________ _____ _____________ ____________________ _____ ______________ _____ _________ _________ ____________ _______ LARYNX MODEL Posterior View HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Larynx Tracheal Rings Found on the Trachea Left Superior Lobe Left Inferior Lobe Heart Right Superior Lobe Right Middle Lobe Right Inferior Lobe Diaphragm HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Hilum (curvature where blood vessels enter lungs) Carina Pulmonary Arteries (Blue) Pulmonary Veins (Red) Bronchioles Apex (points -

Cricoid and Thyroid Cartilage Fracture, Cricothyroid Joint Dislocation

Case Report 170 THE JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE Olgu Sunumu Cricoid and Thyroid Cartilage Fracture, Cricothyroid Joint Dislocation, Pseudofracture Appearance of the Hyoid Bone: CT, MRI and Laryngoscopic Findings Krikoid ve Tiroid Kartilaj Fraktürü, Krikotiroid Eklem Dislokasyonu ve Hiyoid Kemikte Yalancı Kırık Görünümü: BT, MRG ve Laringoskopi Bulguları Yeliz Pekçevik1, İbrahim Çukurova2, Cem Ülker2 1Clinic of Radiology, İzmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, İzmir, Turkey 2Clinic of Otolaryngology, İzmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, Izmir, Turkey Abstract Özet We report a case of cricoid and thyroid cartilage fracture and cricothyroid Künt travma sonrası krikoid ve tiroid kartilaj fraktürü ve krikotiroid eklem joint dislocation after blunt neck trauma. Direct fibreoptic laryngoscopic, dislokasyonu olan bir olgunun direkt fiberoptik laringoskopik, bilgisayarlı to- computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings mografi (BT), manyetik rezonans görüntüleme (MRG) bulgularını sunduk. Hi- were disscused. Pseudofracture appearance of the hyoid bone were reviewed. yoid kemiğin yalancı kırık görünümü gözden geçirildi. (JAEM 2013; 12: 170-3) (JAEM 2013; 12: 170-3) Anahtar kelimeler: Kartilaj, bilgisayarlı tomografi, endoskopi, kırık, manyetik Key words: Cartilage, computed tomography, endoscopy, fracture, magnetic rezonans görüntüleme resonance imaging Introduction Case Report Laryngeal trauma is extremely rare and usually occurs as a result A 84-year-old man, with blunt neck trauma after fallingdown, of blunt trauma. The most common cause of the blunt laryngeal presented to the emergency department with dyspnea. He had stri- trauma is a motor vehicle accident but it can also occur as a result of dor, dysphagia, dysphonia and neck ecchymosis. Laryngeal injury relatively minor insults to the anterior neck that cause posterior com- was suspected by the history and physical examination. -

14 Diagnosing Injuries of the Larynx and Trachea

Thieme-Verlag Sommer-Druck Ernst WN 023832/01/01 20.6.2006 Frau Langner Feuchtwangen Head and Neck Trauma TN 140001 Kap-14 14 Diagnosing Injuries of the Larynx and Trachea Flowchart and Checklist Injuries of the Neck, Chap- Treatment of Injuries of the Larynx, Pharynx, Tra- ter 3, p. 25. chea, Esophagus, and Soft Tissues of the Neck, Chapter 23, p. 209. Surgical Anatomy Anteflexion of the head positions the mandible so that it n The laryngeal muscles are divided into those that open the affords effective protection against trauma to the larynx glottis and those that close it. The only muscle that acts to and cervical trachea. Injury to this region occurs if this open the glottis is the posterior cricoarytenoid (posticus) protective reflex function is inhibited and the head is muscle. prevented from bending forward on impact. Spanning the ventral aspect of the cartilage framework, The rigid framework of the larynx is formed by four the cricothyroid muscle is the only laryngeal muscle inner- cartilages: vated by the superior laryngeal nerve. All other muscles are Q thyroid cartilage; supplied by the inferior (recurrent) laryngeal nerve, which Q epiglottic cartilage; originates from the vagus nerve and, after it loops in the Q arytenoid cartilage; thorax, travels cranially between the trachea and esopha- Q the cricoid cartilage. gus (Fig. 14.1). The thyroid cartilage is made up of two laminae, which The trachea extends from the cricoid cartilage to its bi- meet at approximately a right angle in men and at ca. furcation, a distance of 10–13 cm, or in topographic 120 in women. -

Cricoid Pressure Results in Compression of the Postcricoid Hypopharynx: the Esophageal Position Is Irrelevant

Cricoid Pressure Results in Compression of the Postcricoid Hypopharynx: The Esophageal Position Is Irrelevant Mark J. Rice, MD* BACKGROUND: Sellick described cricoid pressure (CP) as pinching the esophagus between the cricoid ring and the cervical spine. A recent report noted that with the Anthony A. Mancuso, MD† application of CP, the esophagus moved laterally more than 90% of the time, questioning the efficacy of this maneuver. We designed this study to accurately Charles Gibbs, MD* define the anatomy of the Sellick maneuver and to investigate its efficacy. METHODS: Twenty-four nonsedated adult volunteers underwent neck magnetic resonance imaging with and without CP. Measurements were made of the Timothy E. Morey, MD* postcricoid hypopharynx, airway compression, and lateral displacement of the cricoid ring during the application of CP. The relevant anatomy was reviewed. Nikolaus Gravenstein, MD* RESULTS: The hypopharynx, not the esophagus, is what lies behind the cricoid ring and is compressed by CP. The distal hypopharynx, the portion of the alimentary Lori A. Deitte, MD† canal at the cricoid level, was fixed with respect to the cricoid ring and not mobile. With CP, the mean anterioposterior diameter of the hypopharynx was reduced by 35% and the lumen likely obliterated, and this compression was maintained even when the cricoid ring was lateral to the vertebral body. CONCLUSIONS: The location and movement of the esophagus is irrelevant to the efficiency of the Sellick’s maneuver (CP) in regard to prevention of gastric regurgitation into the pharynx. The hypopharynx and cricoid ring move together as an anatomic unit. This relationship is essential to the efficacy and reliability of Sellick’s maneuver. -

Membranes of the Larynx

Membranes of the Larynx: Extrinsic membranes connect the laryngeal apparatus with adjacent structures for support. The thyrohyoid membrane is an unpaired fibro-elastic sheet which connects the inferior surface of the hyoid bone with the superior border of the thyroid cartilage. The thyrohyoid membrane has an opening in its lateral aspect to admit the internal laryngeal nerve and artery Figure 12-08 Thyrohyoid membrane. The Cricotracheal membrane connects the most superior tracheal cartilage with the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage Figure 07-09 Cricotracheal membrane/ligament. Intrinsic Membranes connect the laryngeal cartilages with each other to regulate movement. There are two intrinsic membranes: the conus elasticus and the quadrate membranes. The Conus Elasticus connects the cricoid cartilage with the thyroid and arytenoid cartilages. It is composed of dense fibroconnective tissue with abundant elastic fibers. It can be described as having two parts: The medial cricothyroid ligament is a thickened anterior part of the membrane that connects the anterior apart of the arch of the cricoid cartilage with the inferior border of the thyroid membrane. The lateral cricothyroid membranes originate on the superior surface of the cricoid arch and rise superiorly and medially to insert on the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilages posteriorly, and to the interior median part of the thyroid cartilage anteriorly. Its free borders form the VOCAL LIGAMENTS. Lateral aspect of larynx – right thyroid lamina removed. Figure 12-10 Conus elasticus. A. Right lateral aspect. B. superior aspect The paired Quadrangular Membranes connect the epiglottis with the arytenoid and thyroid cartilages. It arises from the lateral margins of the epiglottis and adjacent thyroid cartilage near the angle. -

Normal Radiological Anatomy of Thyroid Cartilage in 600 Chinese

Yan et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2018) 13:31 DOI 10.1186/s13018-018-0728-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Normal radiological anatomy of thyroid cartilage in 600 Chinese individuals: implications for anterior cervical spine surgery Ying-zhao Yan1,2,3, Chong-an Huang1, Qi Jiang4, Yi Yang3, Jian Lin1, Ke Wang1, Xiao-bin Li1, Hai-hua Zheng4* and Xiang-yang Wang1* Abstract Background: Thyroid cartilage is an important barrier in anterior cervical approach surgery. The objective of this study is to establish normative values for thyroid cartilage at three planes and to determine their significance on preoperative positioning and intraoperative traction in surgery via the anterior cervical approach. Methods: Neck CT scans were collected from 600 healthy adults who did not meet any of the exclusion criteria. Transverse diameters (D1, D2, and D3) of the superior border of the thyroid cartilage (SBTC), inferior border of the thyroid cartilage (IBTC), and the trachea transverse diameters of the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (IBCC) were measured on a horizontal plane. Results: All measured variables had intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) of ≥ 0.7. The differences in transverse diameters on the same plane between males and females were significantly different (all p<0.001). The SBTC is most often at C4 in women (59.5%) and C4/5 in men (36.4%), the IBTC is most often at C5 in women (48.1%) and men (46.2%), and the IBCC is primarily located at C6 in women (45.2%) and C6 or C6/7 in men (34.4%) (all p <0.001). -

Introduction to the Respiratory System

Respiratory System Part 1 Respiration Cardiopulmonary system Respiratory and conducting divisions Three processes 1. Breathing 2. Exchange of gases 3. Use of oxygen Respiration Pulmonary ventilation (breathing): movement of air into and out of the lungs Respiratory system External respiration: O2 and CO2 exchange between the lungs and the blood Transport: O2 and CO2 in the blood Circulatory system Internal respiration: O2 and CO2 exchange between systemic blood vessels and tissues Functional Anatomy Structures Nose Pharynx Larynx Trachea Lungs Bronchial tree Pleurae Nasal cavity Oral cavity Nostril Pharynx Larynx Trachea Left main (primary) Carina of bronchus trachea Right main Left lung (primary) bronchus Right lung Diaphragm Figure 22.1 Nose Functions Provides an airway for respiration Moistens and warms entering air Filters and cleans inspired air Resonating chamber for speech Olfactory receptors Epicranius, frontal belly Root and bridge of nose Dorsum nasi Ala of nose Apex of nose Naris (nostril) Philtrum (a)Surface anatomy Pg 5 study guide Figure 22.2a Frontal bone Nasal bone Septal cartilage Maxillary bone (frontal process) Lateral process of septal cartilage Minor alar cartilages Dense fibrous connective tissue Major alar cartilages (b) External skeletal framework Figure 22.2b Cribriform plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid sinus Frontal sinus Posterior nasal Nasal cavity aperture Nasal conchae Nasopharynx (superior, middle and inferior) Pharyngeal tonsil Nasal meatuses Opening of (superior, middle, pharyngotympanic and inferior) tube Nasal vestibule Uvula Nostril Oropharynx Hard palate Palatine tonsil Soft palate Isthmus of the fauces Tongue Lingual tonsil Laryngopharynx Hyoid bone Larynx Epiglottis Esophagus Vestibular fold Thyroid cartilage Vocal fold Trachea Cricoid cartilage Thyroid gland (c) Illustration Figure 22.3c Pharynx Nasopharynx Oropharynx Laryngopharynx (b) Regions of the pharynx Figure 22.3b Pharynx “Throat” Between internal nares and larynx Three regions Transports air 1.