14 Diagnosing Injuries of the Larynx and Trachea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larynx Anatomy

LARYNX ANATOMY Elena Rizzo Riera R1 ORL HUSE INTRODUCTION v Odd and median organ v Infrahyoid region v Phonation, swallowing and breathing v Triangular pyramid v Postero- superior base àpharynx and hyoid bone v Bottom point àupper orifice of the trachea INTRODUCTION C4-C6 Tongue – trachea In women it is somewhat higher than in men. Male Female Length 44mm 36mm Transverse diameter 43mm 41mm Anteroposterior diameter 36mm 26mm SKELETAL STRUCTURE Framework: 11 cartilages linked by joints and fibroelastic structures 3 odd-and median cartilages: the thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis cartilages. 4 pair cartilages: corniculate cartilages of Santorini, the cuneiform cartilages of Wrisberg, the posterior sesamoid cartilages and arytenoid cartilages. Intrinsic and extrinsic muscles THYROID CARTILAGE Shield shaped cartilage Right and left vertical laminaà laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple) M:90º F: 120º Children: intrathyroid cartilage THYROID CARTILAGE Outer surface à oblique line Inner surface Superior border à superior thyroid notch Inferior border à inferior thyroid notch Superior horns à lateral thyrohyoid ligaments Inferior horns à cricothyroid articulation THYROID CARTILAGE The oblique line gives attachement to the following muscles: ¡ Thyrohyoid muscle ¡ Sternothyroid muscle ¡ Inferior constrictor muscle Ligaments attached to the thyroid cartilage ¡ Thyroepiglottic lig ¡ Vestibular lig ¡ Vocal lig CRICOID CARTILAGE Complete signet ring Anterior arch and posterior lamina Ridge and depressions Cricothyroid articulation -

Neck Dissection Using the Fascial Planes Technique

OPEN ACCESS ATLAS OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY, HEAD & NECK OPERATIVE SURGERY NECK DISSECTION USING THE FASCIAL PLANE TECHNIQUE Patrick J Bradley & Javier Gavilán The importance of identifying the presence larised in the English world in the mid-20th of metastatic neck disease with head and century by Etore Bocca, an Italian otola- neck cancer is recognised as a prominent ryngologist, and his colleagues 5. factor determining patients’ prognosis. The current available techniques to identify Fascial compartments allow the removal disease in the neck all have limitations in of cervical lymphatic tissue by separating terms of accuracy; thus, elective neck dis- and removing the fascial walls of these section is the usual choice for management “containers” along with their contents of the clinically N0 neck (cN0) when the from the underlying vascular, glandular, risk of harbouring occult regional metasta- neural, and muscular structures. sis is significant (≥20%) 1. Methods availa- ble to identify the N+ (cN+) neck include Anatomical basis imaging (CT, MRI, PET), ultrasound- guided fine needle aspiration cytology The basic understanding of fascial planes (USGFNAC), and sentinel node biopsy, in the neck is that there are two distinct and are used depending on resource fascial layers, the superficial cervical fas- availability, for the patient as well as the cia, and the deep cervical fascia (Figures local health service. In many countries, 1A-C). certainly in Africa and Asia, these facilities are not available or affordable. In such Superficial cervical fascia circumstances patients with head and neck cancer whose primary disease is being The superficial cervical fascia is a connec- treated surgically should also have the tive tissue layer lying just below the der- neck treated surgically. -

How the Larynx (Voice Box) Works

How the Larynx (Voice Box) Works Charles R. Larson, PhD If you love opera, or if you admire the voices of pop singers such as Celine Dion or Barbra Streisand, you may have wondered how it is these marvelous singers are able to create such beautiful music with this instrument we call the human voice. You may also know of someone who has a bad voice or has had to have their voice box, or larynx, removed because of illness or injury. The larynx is a critical organ of human speech and singing, and it serves important biological functions as well. Let's have a look at the larynx to understand its functions, what it looks like and how it works. It is thought that the same factors that favored the evolution of air‐breathing animals on earth led to the evolution of the larynx. Lungs are comprised of very delicate tissues that must be maintained within strict biological limits, that is, temperature, humidity and freedom from foreign particles. Thus, along with the first air‐breathing animals, there appeared a primitive sort of larynx, whose one and only function was protection of the lung. This function remains the most important of those the larynx has assumed in subsequent evolutionary developments. Now, of course we recognize that the larynx is critical for human speech and singing. But we also should realize that the larynx is important for swallowing, coughing, vomiting and eliminating contents of the abdomen. If you have ever felt your 'Adam's Apple', then you know where the larynx is. -

Cricoid Pressure: Ritual Or Effective Measure?

R eview A rticle Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9) 620 Cricoid pressure: ritual or effective measure? Nivan Loganathan1, MB BCh BAO, Eugene Hern Choon Liu1, MD, FRCA ABSTRACT Cricoid pressure has been long used by clinicians to reduce the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation. Historically, it is defined by Sellick as temporary occlusion of the upper end of the oesophagus by backward pressure of the cricoid cartilage against the bodies of the cervical vertebrae. The clinical relevance of cricoid pressure has been questioned despite its regular use in clinical practice. In this review, we address some of the controversies related to the use of cricoid pressure. Keywords: cricoid pressure, regurgitation Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9): 620–622 INTRODUCTION imaging showed that in 49% of patients in whom cricoid Cricoid pressure is a technique used worldwide to reduce pressure was applied, the oesophageal position was lateral to the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation in sedated or the cricoid ring.(5) As oesophageal occlusion was thought to be anaesthetised patients. Cricoid pressure can be traced back to crucial, this study challenged the efficacy of cricoid pressure. the late 18th century when it was used to prevent gas inflation More recently, in magnetic resonance imaging studies, Rice et of the stomach during resuscitation from drowning.(1) Sellick al showed that cricoid pressure causes compression of the post- noted that cricoid pressure could both prevent regurgitation cricoid hypopharynx rather than the oesophagus itself. -

3 Approach-Related Complications Following Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Dysphagia, Dysphonia, and Esophageal Perforations

3 Approach-Related Complications Following Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Dysphagia, Dysphonia, and Esophageal Perforations Bharat R. Dave, D. Devanand, and Gautam Zaveri Introduction This chapter analyzes the problems of dysphagia, dysphonia, and esophageal tears during the Pathology involving the anterior subaxial anterior approach to the cervical spine and cervical spine is most commonly accessed suggests ways of prevention and management. through an anterior retropharyngeal approach (Fig. 3.1). While this approach uses tissue planes to access the anterior cervical spine, visceral Dysphagia structures such as the trachea and esophagus and nerves such as the recurrent laryngeal Dysphagia or difficulty in swallowing is a nerve (RLN), superior laryngeal nerve (SLN), and symptom indicative of impairment in the ability pharyngeal plexus are vulnerable to direct or to swallow because of neurologic or structural traction injury (Table 3.1). Complaints such as problems that alter the normal swallowing dysphagia and dysphonia are not rare following process. Postoperative dysphagia is labeled as anterior cervical spine surgery. The treating acute if the patient presents with difficulty in surgeon must be aware of these possible swallowing within 1 week following surgery, complications, must actively look for them in intermediate if the presentation is within 1 to the postoperative period, and deal with them 6 weeks, and chronic if the presentation is longer expeditiously to avoid secondary complications. than 6 weeks after surgery. Common carotid artery Platysma muscle Sternohyoid muscle Vagus nerve Recurrent laryngeal nerve Longus colli muscle Internal jugular artery Anterior scalene muscle Middle scalene muscle External jugular vein Posterior scalene muscle Fig. 3.1 Anterior retropharyngeal approach to the cervical spine. -

The Role of Strap Muscles in Phonation Laryngeal Model in Vivo

Journal of Voice Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 23-32 © 1997 Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia The Role of Strap Muscles in Phonation In Vivo Canine Laryngeal Model Ki Hwan Hong, *Ming Ye, *Young Mo Kim, *Kevin F. Kevorkian, and *Gerald S. Berke Department of Otolaryngology, Chonbuk National University, Medical School, Chonbuk, Korea; and *Division of Head and Neck Surgery, UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. Summary: In spite of the presumed importance of the strap muscles on laryn- geal valving and speech production, there is little research concerning the physiological role and the functional differences among the strap muscles. Generally, the strap muscles have been shown to cause a decrease in the fundamental frequency (Fo) of phonation during contraction. In this study, an in vivo canine laryngeal model was used to show the effects of strap muscles on the laryngeal function by measuring the F o, subglottic pressure, vocal in- tensity, vocal fold length, cricothyroid distance, and vertical laryngeal move- ment. Results demonstrated that the contraction of sternohyoid and sternothy- roid muscles corresponded to a rise in subglottic pressure, shortened cricothy- roid distance, lengthened vocal fold, and raised F o and vocal intensity. The thyrohyoid muscle corresponded to lowered subglottic pressure, widened cricothyroid distance, shortened vocal fold, and lowered F 0 and vocal inten- sity. We postulate that the mechanism of altering F o and other variables after stimulation of the strap muscles is due to the effects of laryngotracheal pulling, upward or downward, and laryngotracheal forward bending, by the external forces during strap muscle contraction. -

Spatial Motion of Arytenoid Cartilage Using Dynamic Computed Tomography Combined with Euler Angles

The Laryngoscope © 2019 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc. Spatial Motion of Arytenoid Cartilage Using Dynamic Computed Tomography Combined with Euler Angles Yanli Ma, MD; Huijing Bao, MD; Xi Wang, MD ; Xi Chen, MS; Zheyi Zhang, MD; Jinan Wang, MD; Peiyun Zhuang, MD ; Jack J. Jiang, MD, PhD ; Azure Wilson, MS; Chenxu Wu, DS Objective: To investigate the feasibility of dynamic computed tomography in recording and describing the spatial motion characteristics of the arytenoid cartilage. Methods: Dynamic computed tomography recorded the real-time motion trajectory of the arytenoid cartilage during inspiration and phonation. A stationary coordinate system was established with the cricoid cartilage as a reference and a motion coordinate system was established using the movement of the arytenoid cartilage. The Euler angles of the arytenoid cartilage movement were calculated by transformation of the two coordinate systems, and the spatial motion characteristics of the arytenoid cartilage were quantitatively studied. Results: Displacement of the cricoid cartilage was primarily inferior during inspiration. During phonation, the displace- ment was mainly superior. When the glottis closed, the superior displacement was about 5–8 mm within 0.56 s. During inspira- tion, the arytenoid cartilage was displaced superiorly approximately 1–2 mm each 0.56 s. The rotation angle was subtle with slight rotation around the XYZ axis, with a range of 5–10 degrees. During phonation, the displacement of the arytenoid cartilage was mainly inferior (about 4–6 mm), anterior (about 2–4 mm) and medial (about 1–2 mm). The motion of the arytenoid carti- lage mainly consisted of medial rolling, and there was an alternating movement of anterior-posterior tilting. -

Head and Neck Trauma

Head and Neck Trauma An Interdisciplinary Approach Bearbeitet von Rainer Ottis Seidl, Michael Herzog, Arneborg Ernst 1. Auflage 2006. Buch. 240 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 13 140001 7 Format (B x L): 19,5 x 27 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Medizin > Chirurgie > Orthopädie- und Unfallchirurgie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Thieme-Verlag Sommer-Druck Ernst WN 023832/01/01 20.6.2006 Frau Langner Feuchtwangen Head and Neck Trauma TN 140001 Kap-14 14 Diagnosing Injuries of the Larynx and Trachea Flowchart and Checklist Injuries of the Neck, Chap- Treatment of Injuries of the Larynx, Pharynx, Tra- ter 3, p. 25. chea, Esophagus, and Soft Tissues of the Neck, Chapter 23, p. 209. Surgical Anatomy Anteflexion of the head positions the mandible so that it n The laryngeal muscles are divided into those that open the affords effective protection against trauma to the larynx glottis and those that close it. The only muscle that acts to and cervical trachea. Injury to this region occurs if this open the glottis is the posterior cricoarytenoid (posticus) protective reflex function is inhibited and the head is muscle. prevented from bending forward on impact. Spanning the ventral aspect of the cartilage framework, The rigid framework of the larynx is formed by four the cricothyroid muscle is the only laryngeal muscle inner- cartilages: vated by the superior laryngeal nerve. -

Interaction Between the Thyroarytenoid and Lateral Cricoarytenoid

Interaction Between the Thyroarytenoid and Lateral Cricoarytenoid Jun Yin1 Muscles in the Control Speech Production Laboratory, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, of Vocal Fold Adduction University of California, Los Angeles, 31-24 Rehabilitation Center, 1000 Veteran Avenue, and Eigenfrequencies Los Angeles, CA 90095-1794 2 Although it is known vocal fold adduction is achieved through laryngeal muscle activa- Zhaoyan Zhang tion, it is still unclear how interaction between individual laryngeal muscle activations Speech Production Laboratory, affects vocal fold adduction and vocal fold stiffness, both of which are important factors Department of Head and Neck Surgery, determining vocal fold vibration and the resulting voice quality. In this study, a three- University of California, Los Angeles, dimensional (3D) finite element model was developed to investigate vocal fold adduction 31-24 Rehabilitation Center, and changes in vocal fold eigenfrequencies due to the interaction between the lateral cri- 1000 Veteran Avenue, coarytenoid (LCA) and thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles. The results showed that LCA con- Los Angeles, CA 90095-1794 traction led to a medial and downward rocking motion of the arytenoid cartilage in the e-mail: [email protected] coronal plane about the long axis of the cricoid cartilage facet, which adducted the pos- terior portion of the glottis but had little influence on vocal fold eigenfrequencies. In con- trast, TA activation caused a medial rotation of the vocal folds toward the glottal midline, resulting in adduction of the anterior portion of the glottis and significant increase in vocal fold eigenfrequencies. This vocal fold-stiffening effect of TA activation also reduced the posterior adductory effect of LCA activation. -

The Cricoid Cartilage and the Esophagus Are Not Aligned in Close to Half of Adult Patients

CARDIOTHORACIC ANESTHESIA, RESPIRATION AND AIRWAY 503 The cricoid cartilage and the esophagus are not aligned in close to half of adult patients [Le cartilage cricoïde et l’œsophage ne sont pas alignés chez près de la moitié des adultes] Kevin J. Smith MD,* Shayne Ladak MD,† Peter T.-L. Choi MD FRCPC,* Julian Dobranowski MD FRCPC† Purpose: To determine the frequency and degree of lateral dis- de 3,3 mm ± 1,3 mm d’écart type par rapport à la ligne médiane du placement of the esophagus relative to the cricoid cartilage cricoïde. Soixante-quatre pour cent des déplacements latéraux de (“cricoid”) using computed tomography (CT) images of normal l’œsophage allaient au delà du bord latéral du cricoïde (moyenne de necks. 3,2 mm ± 1,2 mm d’écart type). Nous avons noté une distribution Methods: Fifty-one cervical CT scans of clinically normal patients relativement normale des mesures groupées de pourcentage de were reviewed retrospectively. Esophageal diameter, distance diamètre œsophagien déplacés. De ces déplacements, 48 % présen- between the midline of the cricoid and the midline of the esopha- taient plus de 15 % de la largeur totale de l’œsophage déplacé gus, and distance between the lateral border of the cricoid and the latéralement et 20 % avaient plus de 20 % de déplacement. lateral border of the esophagus were measured. Conclusion : La fréquence de déplacement latéral de l’œsophage Results: Lateral esophageal displacement was observed in 49% d’un certain degré par rapport au cricoïde est de 49 %. (25/51) of CT images. When present, the mean length of displaced esophagus relative to the midline of the cricoid was 3.3 mm ± SD 1.3 mm. -

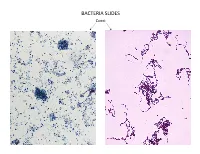

Bacteria Slides

BACTERIA SLIDES Cocci Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES _______________ __ BACTERIA SLIDES Spirilla BACTERIA SLIDES ___________________ _____ BACTERIA SLIDES Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES ________________ _ LUNG SLIDE Bronchiole Lumen Alveolar Sac Alveoli Alveolar Duct LUNG SLIDE SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL Superior Concha Auditory Tube Middle Concha Opening Inferior Concha Nasal Cavity Internal Nare External Nare Hard Palate Pharyngeal Oral Cavity Tonsils Tongue Nasopharynx Soft Palate Oropharynx Uvula Laryngopharynx Palatine Tonsils Lingual Tonsils Epiglottis False Vocal Cords True Vocal Cords Esophagus Thyroid Cartilage Trachea Cricoid Cartilage SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View Hyoid Bone Superior Horn Thyroid Cartilage Inferior Horn Thyroid Gland Cricoid Cartilage Trachea Tracheal Rings LARYNX MODEL Posterior View Epiglottis Hyoid Bone Vocal Cords Epiglottis Corniculate Cartilage Arytenoid Cartilage Cricoid Cartilage Thyroid Gland Parathyroid Glands LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View ____________ _ ____________ _______ ______________ _____ _____________ ____________________ _____ ______________ _____ _________ _________ ____________ _______ LARYNX MODEL Posterior View HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Larynx Tracheal Rings Found on the Trachea Left Superior Lobe Left Inferior Lobe Heart Right Superior Lobe Right Middle Lobe Right Inferior Lobe Diaphragm HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Hilum (curvature where blood vessels enter lungs) Carina Pulmonary Arteries (Blue) Pulmonary Veins (Red) Bronchioles Apex (points -

Shifteh Retropharyngeal Danger and Paraspinal Spaces ASHNR 2016

Acknowledgment • Illustrations Courtesy Amirsys, Inc. Retropharyngeal, Danger, and Paraspinal Spaces Keivan Shifteh, M.D. Professor of Clinical Radiology Director of Head & Neck Imaging Program Director, Neuroradiology Fellowship Montefiore Medical Center Albert Einstein College of Medicine Bronx, New York Retropharyngeal, Danger, and Retropharyngeal Space (RPS) Paraspinal Spaces • It is a potential space traversing supra- & infrahyoid neck. • Although diseases affecting these spaces are relatively uncommon, they can result in significant morbidity. • Because of the deep location of these spaces within the neck, lesions arising from these locations are often inaccessible to clinical examination but they are readily demonstrated on CT and MRI. • Therefore, cross-sectional imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of these spaces. Retropharyngeal Space (RPS) Retropharyngeal Space (RPS) • It is seen as a thin line of fat between the pharyngeal • It is bounded anteriorly by the MLDCF (buccopharyngeal constrictor muscles anteriorly and the prevertebral fascia), posteriorly by the DLDCF (prevertebral fascia), and muscles posteriorly. laterally by sagittaly oriented slips of DLDCF (cloison sagittale). Alar fascia (AF) Retropharyngeal Space • Coronally oriented slip of DLDCF (alar fascia) extends from • The anterior compartment is true or proper RPS and the the medial border of the carotid space on either side and posterior compartment is danger space. divides the RPS into 2 compartments: Scali F et al. Annal Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015 May 19. Retropharyngeal Space Danger Space (DS) • The true RPS extends from the clivus inferiorly to a variable • The danger space extends further inferiorly into the posterior level between the T1 and T6 vertebrae where the alar fascia mediastinum just above the diaphragm.