Use of Sweeteners in Animal Nutrition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweet Success

[Sweetners] Vol. 25 No. 2 Summer 2015 Sweet Success By Judie Bizzozero, Senior Editor In light of increasing consumer demand for less caloric, healthier and “natural” products featuring lower sugar content and non-GMO ingredients, formulators are seeking out versatile ingredients that not only are easy to integrate into food and beverages, but also deliver specific and reliable health benefits. “‘Natural’ sweeteners are gaining favor among consumers due to the increased focus on products, in all categories, that are ‘free-from’ and non-GMO,” said Rudy Wouters, vice president, BENEO Technology Center, Antwerp Area, Belgium. “Consumers are looking to manufacturers to deliver products that are natural, but also lower in sugar content for the maintenance of a more healthy diet and lifestyle.” Clean-Label Trending According to 2014 data from Tate & Lyle, Hoffman Estates, Illinois, 65 percent of consumers in the United States are looking for calories on package labels. In addition to calorie reduction, 2014 data from Harleysville, Pennsylvania-based Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) found 53 percent of consumers are looking for products with simpler ingredient lists. “The dual demand for calorie reduction and simpler ingredient lists makes zero-calorie sweeteners like stevia and monk fruit an ideal option for food and beverage manufacturers. And we’re already seeing manufacturers adopt these trending sweeteners in their formulations,” said Amy Lauer, marketing manager, Tate & Lyle North America. “In fact, stevia and monk fruit are the only high- potency sweeteners to see growth in new product launches from 2013 to 2014 in the United States [Innova, 2014]. Stevia in particular is gaining momentum with a 103-percent increase in new product launches from 2013 to 2014.” Tate & Lyle’s stevia-based zero-calorie sweetener meets consumer demand for low-calorie and low- sugar products and achieves 50 percent or more sugar-reduction levels, Lauer said. -

Thaumatin Is Similar to Water in Blood Glucose Response in Wistar Rats Warid Khayata1, Ahmad Kamri2, Rasha Alsaleh1

International Journal of Academic Scientific Research ISSN: 2272-6446 Volume 4, Issue 2 (May - June 2016), PP 36-42 www.ijasrjournal.org Thaumatin is similar to water in blood glucose response in Wistar rats Warid Khayata1, Ahmad Kamri2, Rasha Alsaleh1 1 (Department of Analytical and Food Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy/ University of Aleppo, Aleppo, Syria) 2 (Department of Physiology, Faculty of Sciences/ University of Aleppo, Aleppo, Syria) ABSTRACT: The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of thaumatin; a sweet tasting protein, compared to a natural sweetener; sucrose and a synthetic one; aspartame on blood glucose level and body weight in male Wistar rats. Sucrose, aspartame, and thaumatin solutions have been administrated orally every day to adult male Wistar rats for 8 consecutive weeks. Within this period, blood glucose was monitored during two hours and body weight was measured every two weeks. It was found that compared to water, aspartame and thaumatin did not elevate blood glucose at all. Also, neither aspartame nor thaumatin affected body weight. Subsequently, thaumatin can be considered as a safer and healthier sweetener than aspartame or sucrose, because it is natural and do not cause elevating in blood glucose. Keywords: Blood glucose, Body weight, Sweetener, Thaumatin, Wistar rat GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT www.ijasrjournal.org 36 | Page International Journal of Academic Scientific Research ISSN: 2272-6446 Volume 4, Issue 2 (May - June 2016), PP 36-42 I. INTRODUCTION Sugar obtained from sugar cane or beet is widely used in many food products to give sweetness, viscosity, and consistency. Furthermore, it has a role in the preservation of foods [1]. -

Reports of the Scientific Committee for Food

Commission of the European Communities food - science and techniques Reports of the Scientific Committee for Food (Sixteenth series) Commission of the European Communities food - science and techniques Reports of the Scientific Committee for Food (Sixteenth series) Directorate-General Internal Market and Industrial Affairs 1985 EUR 10210 EN Published by the COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Directorate-General Information Market and Innovation Bâtiment Jean Monnet LUXEMBOURG LEGAL NOTICE Neither the Commission of the European Communities nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information This publication is also available in the following languages : DA ISBN 92-825-5770-7 DE ISBN 92-825-5771-5 GR ISBN 92-825-5772-3 FR ISBN 92-825-5774-X IT ISBN 92-825-5775-8 NL ISBN 92-825-5776-6 Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1985 ISBN 92-825-5773-1 Catalogue number: © ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels · Luxembourg, 1985 Printed in Luxembourg CONTENTS Page Reports of the Scientific Committee for Food concerning - Sweeteners (Opinion expressed 14 September 1984) III Composition of the Scientific Committee for Food P.S. Elias A.G. Hildebrandt (vice-chairman) F. Hill A. Hubbard A. Lafontaine Mne B.H. MacGibbon A. Mariani-Costantini K.J. Netter E. Poulsen (chairman) J. Rey V. Silano (vice-chairman) Mne A. Trichopoulou R. Truhaut G.J. Van Esch R. Wemig IV REPORT OF THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE FOR FOOD ON SWEETENERS (Opinion expressed 14 September 1984) TERMS OF REFERENCE To review the safety in use of certain sweeteners. -

GRAS Notice 920, THAUMATIN II

GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 920 https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-notice-inventory Form Approved: OMB No. 0910-0342; Expiration Date: 02/29/2016 (See last page for OMB Statement) FDA USE ONLY GRN NUMBER DATE OF RECEIPT DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES ESTIMATED DAILY INTAKE INTENDED USE FOR INTERNET Food and Drug Administration GENERALLY RECOGNIZED AS SAFE NAME FOR INTERNET (GRAS) NOTICE KEYWORDS Transmit completed form and attachments electronically via the Electronic Submission Gateway (see Instructions); OR Transmit completed form and attachments in paper format or on physical media to: Office of Food Additive Safety (HFS-200), Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration, 5100 Paint Branch Pkwy., College Park, MD 20740-3835. PART I – INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION ABOUT THE SUBMISSION 1. Type of Submission (Check one) New Amendment to GRN No. Supplement to GRN No. 2. All electronic files included in this submission have been checked and found to be virus free. (Check box to verify) 3a. For New Submissions Only: Most recent presubmission meeting (if any) with FDA on the subject substance (yyyy/mm/dd): 3b. For Amendments or Supplements: Is your (Check one) amendment or supplement submitted in Yes If yes, enter the date of response to a communication from FDA? No communication (yyyy/mm/dd): PART II – INFORMATION ABOUT THE NOTIFIER Name of Contact Person Position Yuri Gleba, Ph.D. Chief Executive Officer Company (if applicable) 1a. Notifier Nomad Bioscience GmbH Mailing Address (number and street) Biozentrum Halle, Weinbergweg 22 City State or Province Zip Code/Postal Code Country Halle/Saale Saxony-Anhalt D-06120 Germany Telephone Number Fax Number E-Mail Address 49 345 1314 2606 4934513142601 [email protected] Name of Contact Person Position Kristi 0 . -

A Novel Approach to Dietary Exposure

Technical stakeholder event, 3 December 2019 A novel approach to dietary exposure Protocol for the exposure assessment as part of the safety assessment of sweeteners under the food additives re-evaluation programme Davide Arcella DATA Unit Sweeteners, to be re-evaluated under Regulation (EC) No 257/2010 E Number Food additive(s) Substance E 420 Sorbitols E 420 (i) Sorbitol E 420(ii) Sorbitol syrup E 421 Mannitols E 421(i) Mannitol by hydrogenation E 421(ii) Mannitol manufactured by fermentation E 950 Acesulfame K E 951(a) Aspartame(a) E 952 Cyclamates E 952(i) Cyclamic acid E 952(ii) Sodium cyclamate E 952(iii) Calcium cyclamate E 953 Isomalt E 954 Saccharin and its Na, K and Ca salts E 954(i) Saccharin E 954(ii) Sodium saccharin E 954(iii) Calcium saccharin E 954(iv) Potassium saccharin E 955 Sucralose E 957 Thaumatin E 959 Neohesperidine dihydrochalcone E 961 Neotame E 962 Salt of aspartame-acesulfame E 965 Maltitols E 965(i) Maltitol E 965(ii) Maltitol syrup E 966 Lactitol E 967 Xylitol 2 E 968 Erythritol Refined exposure assessment of food additives under re-evaluation Dietary exposure assessment Occurrence Consumption Exposure Occurrence data Call for data (batch 7) launched for sweeteners in 2018 (January-October) ▪ Use levels ▪ Analytical results in food and beverages intended for human consumption. From: ▪ National authorities/organisations of the Member States, and ▪ Interested business operators and other parties (e.g. individual food manufacturers, food manufacturer associations, research institutions, academia, food business operators and other stakeholders). An additional call on occurrence data on aspartame (E 951) will be launched to update the assessment of exposure to aspartame (E 951), as well as to assess the total aspartame exposure from the use of the salt of aspartame-acesulfame (E 962) and aspartame (E 951). -

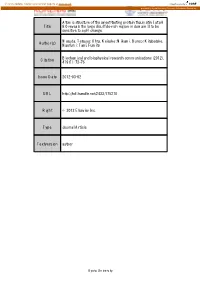

Title Atomic Structure of the Sweet-Tasting Protein

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Atomic structure of the sweet-tasting protein thaumatin I at pH Title 8.0 reveals the large disulfide-rich region in domain II to be sensitive to a pH change. Masuda, Tetsuya; Ohta, Keisuke; Mikami, Bunzo; Kitabatake, Author(s) Naofumi; Tani, Fumito Biochemical and biophysical research communications (2012), Citation 419(1): 72-76 Issue Date 2012-03-02 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/175270 Right © 2012 Elsevier Inc. Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Atomic structure of the sweet-tasting protein thaumatin I at pH 8.0 reveals the large disulfide-rich region in domain II to be sensitive to a pH change Tetsuya Masudaab*, Keisuke Ohtaab, Bunzo Mikamic , Naofumi Kitabataked , and Fumito Taniab aDivision of Food Science and Biotechnology, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto, 611-0011, Japan, bDepartment of Natural Resources, Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto, 611-0011, Japan, and cDivision of Applied Life Sciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto, 611-0011, Japan and dDepartment of Foods and Human Nutrition, Notre Dame Seishin University, Okayama 700-8516, Japan Correspondence email: [email protected] 1 Abstract Thaumatin, an intensely sweet-tasting plant protein, elicits a sweet taste at 50 nM. Although the sweetness remains when thaumatin is heated at 80C for 4 h under acid conditions, it rapidly declines when heating at a pH above 7.0. To clarify the structural difference at high pH, the atomic structure of a recombinant thaumatin I at pH 8.0 was determined at a resolution of 1.0 Å. -

Sweeteners (Sugar Alternatives)

www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal Sweeteners (sugar alternatives) Sweeteners provide an intense sweet flavour. They have become increasing popular as people look for different ways to satisfy their sweet tooth, without the associated energy (kilojoules or calories) of regular sugar. Sweeteners can be divided in to three categories: • Artificial sweeteners • Nutritive sweeteners • Natural intense sweeteners Artificial sweeteners Artificial or non-nutritive sweeteners are often used as an alternative to sugar. These sweeteners are energy (kilojoule or calorie) free. Artificial sweeteners are found in a wide range of food and drink products in the supermarket. Many are ‘tabletop sweeteners’ which can be used to add sweetness to tea, coffee, cereal and fruit in place of sugar. There are also a number of other products such as cordials, soft drinks, jellies, yoghurt, ice-cream, chewing gum, lollies, desserts and cakes which use these sweeteners. These products are often labelled as ‘diet’, ‘low joule’ or ‘no sugar’. The most commonly used artificial sweeteners in the Australian food supply are: Name Code number Brand name Acesulphame K 950 Hermesetas® Sunnett® Alitame 956 Aclame® Aspartame 951 Equal® Equal Spoonful® Hermesetas® Nutrasweet® Cyclamate 952 Sucaryl® Neotame 961 Saccharin 954 Sugarella® Sugarine® Sweetex® Sucralose 955 Splenda® PAGE 1 www.health.nsw.gov.au/heal Nutritive sweeteners Nutritive sweeteners are based on different types of carbohydrates. Products that contain these sweeteners may be labeled as ‘carbohydrate modified’. The sweeteners -

Positive Allosteric Modulators of the Human Sweet Taste Receptor Enhance Sweet Taste

Positive allosteric modulators of the human sweet taste receptor enhance sweet taste Guy Servanta,1,2, Catherine Tachdjiana,1, Xiao-Qing Tanga, Sara Wernera, Feng Zhanga, Xiaodong Lia, Poonit Kamdara, Goran Petrovica, Tanya Ditschuna, Antoniette Javaa, Paul Brusta, Nicole Brunea, Grant E. DuBoisb, Mark Zollera, and Donald S. Karanewskya aSenomyx, Inc., La Jolla, CA 92121; and bGlobal Research and Technology, The Coca-Cola Company, Atlanta, GA 30301 Edited* by Solomon Snyder, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and approved January 25, 2010 (received for review October 12, 2009) To identify molecules that could enhance sweetness perception, concentrations (4, 5) and therefore potentially improving the we undertook the screening of a compound library using a cell- palatability and flavor profile of several consumer products. based assay for the human sweet taste receptor and a panel of Sweet taste is mediated by an obligate heterodimeric receptor selected sweeteners. In one of these screens we found a hit, SE-1, composed of two distinct subunits (G protein-coupled receptors, which significantly enhanced the activity of sucralose in the assay. GPCRs), T1R2 and T1R3, located at the surface of taste At 50 μM, SE-1 increased the sucralose potency by >20-fold. On receptor cells in the taste buds (6, 7). These subunits, members the other hand, SE-1 exhibited little or no agonist activity on its of family C GPCRs, possess a large extracellular N-terminal own. SE-1 effects were strikingly selective for sucralose. Other domain, the Venus flytrap domain (VFT), linked to the seven- popular sweeteners such as aspartame, cyclamate, and saccharin transmembrane C-terminal domain (TMD) by a shorter cys- were not enhanced by SE-1 whereas sucrose and neotame potency teine-rich domain (6–8). -

Low Calorie High-Intensity Sweeteners Riaz Khan, Vincent Aroulmoji

Low Calorie High-Intensity Sweeteners Riaz Khan, Vincent Aroulmoji To cite this version: Riaz Khan, Vincent Aroulmoji. Low Calorie High-Intensity Sweeteners. International journal of advanced Science and Engineering, Mahendra Publications, 2018, 5, 10.29294/ijase.5.2.2018.934-947. hal-03093639 HAL Id: hal-03093639 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03093639 Submitted on 4 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Vol.5 No.2 934-947 (2018) 934 E-ISSN: 2349 5359; P-ISSN: 2454-9967 Low Calorie High-Intensity Sweeteners Riaz Khan1., Vincent Aroulmoji2 1Rumsey, 6 Old Bath Road, Sonning, Reading, England, UK 2 Mahendra Engineering Colleges, Mahendra Educational Institutions, Mahendhirapuri, Mallasamudram - 637 503, Namakkal District, Tamil Nadu, India. ABSTRACT: The review on low-calorie, High-intensity Sweeteners (HIS), synthetic and natural, will focus particularly on those sweeteners which have already received approval as food additives from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the Federal Drug Administration -

Type of the Paper (Article

Table S1. Methodologies Utilized for Intake Assessments Conducted for Low-/No-Calorie Sweeteners in Asia. Food Chemical Data Assessment Model(s) Country Population Group Sweeteners Consumption Reference Examined (n) Investigated Concentration Presence Market Share Data Details Data Data Data China Female college ☐Ace-K Quantitative ☒MPL ☐Yes ☐Yes ☒Deterministic Liu et al., 2012 [20] students, 18–25 ☐Aspartame FFQ ☐Reported Use ☒No ☒No ☒Simple Distribution years (n = 2044) ☒Cyclamate Level ☐Probabilistic Cohort of female ☒Saccharin ☒Analytical college students ☐Steviol Data (n = 252) 2 models: attending 10 ☐Sucralose (A) Point estimate: average different schools in ☐Thaumatin Analytical population intake + average the Guangdong measurement in sweetener concentration province preserved fruits (B) Simple distribution: (n = 252) and Individual consumption data + MPL MPL China All ages, ≥2 years; 2 ☐Ace-K 3*24-hour ☒MPL 1 ☐Yes ☐Yes ☐Deterministic Cao et al., 2016 to 3 years; 4–9 ☐Aspartame recalls, FFQ (1- ☐Reported Use ☒No ☒No ☒Simple Distribution [21] years; 10–17 years; ☒Cyclamate year) and/or Level ☐Probabilistic 18–59 years; >60 ☐Saccharin weighed ☐Analytical years (n = NR) ☐Steviol record Data Individual consumption data + Participants of ☐Sucralose included as MPL 1 China Nutrition ☐Thaumatin part of China GB 2760-2014 - and Health Survey Nutrition and National Health (2002) Health Survey and Family (2002) Planning Commission of Nutrients 2018, 10, x; doi: FOR PEER REVIEW www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients Nutrients 2018, 10, x FOR PEER -

GRAS Notice738, Thaumatin

GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 738 https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/default.htm THAUMATIN SWEETENER AND FOOD FLAVOR MODIFIER NOMAD BIOSCIENCE GmbH Biozentrum Halle Weinbergweg 22 D-06120 Halle/Saale Germany Tel. 49 345 555 9887 Fax. 49 345 1314 2601 16 October, 2017 Antonia Mattia, Ph.D. Director, Division of Biotechnology and GRAS Notice Review (HFS-255) Office of Food Additive Safety Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Food and Drug Administration 5100 Paint Branch Parkway College Park, MD 20740 Re: GRAS Notice for THAUMATIN Sweetener and Food Flavor Modifier Dear Dr. Mattia, Nomad Bioscience GmbH ("Nomad"; “Notifier”) is submitting this GRAS Notice for its THAUMATIN sweetener and food flavor modifier product. NOMAD has concluded, under FDA’s Final Rule pertaining to 21 CFR 170 (August 17, 2016), that the naturally occurring proteins comprising THAUMATIN are Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) for use as a sweetener and flavor modifier in various food products. Thaumatin is comprised of several related proteins extracted from the Katemfe fruit of the native African bush Thaumatococcus danielli. The pulp of the arils of the fruit contain thaumatin proteins and has been used as a sweetener, flavor modifier and enhancer in native cuisines in West Africa for more than one hundred years. The active taste-modifying principles reside predominantly in the closely related proteins thaumatin I and thaumatin II. In the USA, EU, Japan and elsewhere, isolates of the Katemfe fruit have been marketed commercially since the mid-1990s under various trade names (e.g. Talin®; San Sweet T-100®), as low-calorie sweeteners and flavor modifiers. -

Nutritive and Non-Nutritive Sweeteners: a Review Merin Jacob 1, Abhay Mani Tripathi2, Gunjan Yadav3, Sonali Saha4

REVIEW ARTICLE Jacob M. et al.: Nutritive and Non-Nutritive Sweetners Nutritive and Non-Nutritive Sweeteners: A Review Merin Jacob 1, Abhay Mani Tripathi2, Gunjan Yadav3, Sonali Saha4 1- P.G Student, Dept. Of Pedodontics & Preventive Dentistry, Sardar Patel Post Correspondence to: Graduate Institute of Dental & Medical Sciences, Lucknow. 2- Professor & Head, Dept. Dr. Merin Jacob, .G Student, Dept. Of Pedodontics & Of Pedodontics & Preventive, Dentistry, Sardar Patel Post Graduate Institute of Dental Preventive Dentistry, Sardar Patel Post Graduate Institute of & Medical Sciences, Lucknow. 3,4- Reader, Dept. Of Pedodontics & Preventive Dental & Medical Sciences, Lucknow. Dentistry, Sardar Patel Post Graduate Institute of Dental & Medical Sciences, Lucknow. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT The importance of sugar as the principal dietary substrate that drives the caries process has led to growing interest in sugar substitutes. Dynamic relation exists between sugars and oral health. Dental profession shares an interest in the search for safe, palatable sugar substitutes to prevent dental caries and have attempted to persuade their patients to adopt special dietary programs to limit the frequency with which sugar containing foods are ingested. Hence, this paper reviews the role of various nutritive and non-nutritive sweeteners and its role in prevention of dental caries which provides a framework for consumers and health professional in maintaining the intake of sugar. KEYWORDS: Cariogenicity, Dental Caries, Sugars, Sugar Substitutes. AA 4 aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION and sugar beet are major industrial sources of sugar. Dental caries is a infectious disease, in which sugar Sucrose is a non-reducing disaccharide and can be readily present in plaque together with cariogenic bacteria can hydrolyzed.