Construction of Context and Language Acquisition Through Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carolina Gómez Y Su Hijo, Thomas

NÚMERO E special N.º 161 ● 28 DE MAYO DE 2020 COLOMBIA $ 14.500 ISSN 2256-330X 16100 7 706821 014013 EN EXCLUSIVA ANDREA CAROLINA GÓMEZ Y NOCETI NOS PRESENTA SU HIJO, THOMAS, A LUCIAN POSAN JUNTOS POR PRIMERA VEZ, UN AMOR A PRUEBA DE TODO ● SOFÍA VERGARA Y SU IMBORRABLE SONRISA, A PESAR DE LA TORMENTA ● ARCHIE CELEBRA SU PRIMER CUMPLEAÑOS EN LOS ÁNGELES ● GUSI, UNO DE LOS ‘CHEFS’ MÁS SORPRENDENTES DE LA CUARENTENA Untitled-2 1 26/05/20 9:52 a.m. 66 44 NÚMERO 161 28 DE MAYO DE 2020 6 • Tata Harper nos abre las puertas de su casa 14 • Sofía Vergara y su imborrable sonrisa 16 • Los artistas y su solidaridad con Colombia 18 • Grandes Momentos Internacionales FOTO : HERNÁN PUENTES. VESTUARIO @MIO.CORAL 26 • Grandes Momentos en Colombia 36 • Entrevista con Salma Hayek 40 • Andrea Noceti nos presenta a Lucian desde Miami 44 • Portada: Carolina Gómez y su hijo, Thomas 50 • Tata Gnecco y Coraima Torres 16 50 nos cuentan sus historias de madres e hijos 24/7 56 • Alejandra Azcárate conquista Instagram Live 59 • Los chefs más sorprendentes durante la cuarentena 66 • En casa de las celebrities 68 • ¡HOLA! Fashion 70 • ¡HOLA! Ama 72 • Belleza 74 • Salud 76 • Entrevista con Marie Kondo 78 • Cocina 85 • Media hora con Ilia Calderón JOSE VEIRA ANDRÉS OYUELA 40 Foto: Foto: SÍGUENOS EN NUESTRAS REDES: HolaColombia @Hola_col @Hola_col Suscripciones y Servicio al Cliente Línea Nacional 01 8000 110990 Bogotá: (1) 426 6000 / Medellín: (4) 605 2605 Director General de EL TIEMPO Casa Editorial: Roberto Pombo Gerente General de Cali: (2) 489 9830 / Barranquilla: (5) 385 3564 EL TIEMPO Casa Editorial: Juan Guillermo Amaya Subdirector de Información de EL ISSN 2256-330X TIEMPO Casa Editorial: Andrés Mompotes Gerente de Mercadeo: Diana Gómez Gerente de Revistas: María Cristina Amaya / [email protected] Gerente Ejecutivo EL TIEMPO Fundador Jorge Stellabatti R. -

Rompiendo Esquemas

elecciones nuestras Analizando nos movemos nos Yo elijo trabajando? ¿Están si tengo un problema caminorecorrido dónde Por Sopa profesional tiempo propio Proyectos Desmontando motivos Las profesiones prohibidas Las Profesionales invisibles Descentralizando quién? a cuida ¿Quién de vida el empleo SMS ¿Quién tiene responsabilidad? Conociéndonos de vida Proyectos Quiero ser ¿Recorremos el mismo camino? Camino recorrido SMS quién cuida a quién recorrido Los ¿Cómo camino juguetes conciliamos de la Desmontando en el empleo esto? Televisión motivos Buscando empleo centralidad Tiempo propio Camino quiero Tiempo propio ¿Quién tiene responsabilidad? Historia escucharte quiero ser... ¿Recorremos el mismo camino? Desmontando motivos recorrido recuerda la recuerda a quiénes recuerda A quiénes A doble jornada la Historia Si tengo un problema Turistas S S Quiero M escucharte en el IES Desmontando Y me motivos gustaría ser Quién trabaja en el Insti Profesionales invisibles Pros y contras analizando nuestras elecciones ¿cómo lo lograron? Tiempo propio Nuestra vida de afectos Bailarines y camioneras ¿Cómo lo lograron? camino? mismo el ¿Recorremos Mercado ¿Sólo sé que no sé nada? propio laboral tiempo elijo Yo El mundo al revés Rompiendo esquemas Programa de orientación académica y profesional d a e t as r e esto? n a B e cen pio Camino quiero ¿Quién ti es quiero ser... ¿Recorremos el mismo camino? recorrido a quié doble jornada Tu Y m gu Quién trabaja en el Insti Profesion Pros y contr analizando nuestras elecciones ¿cómo lo log Tiempo Bailarines y cam s el mismo camino? mismo el s o ¿Sólo sé que no o elijo propio mpo Y rompiendo esquemas d a e t as r e esto? n a B e cen pio Camino quiero ¿Quién ti es quiero ser.. -

Memorias De Un Amigo Imaginario Matthew Dicks

Memorias de un amigo imaginario Matthew Dicks Traducción de Victoria Alonso Blanco Índice Capítulo 27 Cubierta Capítulo 28 Memorias de un amigo imaginario Capítulo 29 Capítulo 1 Capítulo 30 Capítulo 2 Capítulo 31 Capítulo 3 Capítulo 32 Capítulo 4 Capítulo 33 Capítulo 5 Capítulo 34 Capítulo 6 Capítulo 35 Capítulo 7 Capítulo 36 Capítulo 8 Capítulo 37 Capítulo 9 Capítulo 38 Capítulo 10 Capítulo 39 Capítulo 11 Capítulo 40 Capítulo 12 Capítulo 41 Capítulo 13 Capítulo 42 Capítulo 14 Capítulo 43 Capítulo 15 Capítulo 44 Capítulo 16 Capítulo 45 Capítulo 17 Capítulo 46 Capítulo 18 Capítulo 47 Capítulo 19 Capítulo 48 Capítulo 20 Capítulo 49 Capítulo 21 Capítulo 50 Capítulo 22 Capítulo 51 Capítulo 23 Capítulo 52 Capítulo 24 Capítulo 53 Capítulo 25 Capítulo 54 Capítulo 26 Capítulo 55 Capítulo 56 Capítulo 62 Capítulo 57 Epílogo Capítulo 58 Agradecimientos Capítulo 59 Agradecimientos Capítulo 60 Créditos Capítulo 61 Acerca de Random House Mondadori Para Clara Capítulo 1 Os voy a contar lo que sé: Me llamo Budo. Hace cinco años que estoy en el mundo. Cinco años es mucho tiempo para alguien como yo. Fue Max quien me puso ese nombre. Max es el único ser humano que puede verme. Los padres de Max dicen que soy un «amigo imaginario». Me gusta mucho la maestra de Max, la señorita Gosk. No me gusta la otra maestra de Max, la señorita Patterson. No soy imaginario. Capítulo 2 Soy un amigo imaginario con suerte. Llevo más tiempo en el mundo que casi todos los amigos imaginarios. Una vez conocí a uno que se llamaba Philippe. -

P20-21 Layout 1

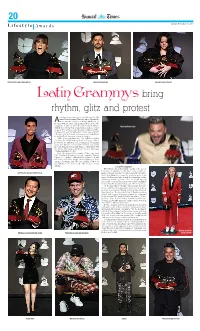

20 Established 1961 Lifestyle Awards Sunday, November 17, 2019 Puerto Rican singer Kany Garcia Musician El Guincho Spaniard singer Rosalia n undercurrent of protest streaked through the 20th annual Latin Grammys Thursday, where Spanish fla- Amenco futurist Rosalia scored Best Album and led the night with five wins. Chilean singer Mon Laferte-who snagged a trophy for Best Alternative Music Album- Musician Pedro Capo walked the red carpet in a long black trenchcoat before dropping it to reveal her bare breasts, emblazoned with a message that read “In Chile they torture, rape and kill,” referring to the violent anti-government protests that have rocked the South American country for weeks. “Chile, your pain hurts me,” the balladeer said in accepting her award at the gala in Las Vegas, reading a poem from the Chilean poet La Chinganera. Nicaraguan singer Luis Enrique also seized the moment in scooping the Latin Grammy for best folk album, a collaboration with the C4 Trio. “Nicaragua is still at war,” he said. “Nicaragua continues fighting to be free.” Puerto Rican Residente, member of the iconic band Calle 13, dedicated his short form video award for “Banana Papaya,” to “equality.” “Although it has nothing to do with the video, this is for all the people fighting in Latin America,” Residente said. “We can’t continue to allow our governments to take us for fools.” “We need to continue fighting.” Long live reggaeton Fellow Puerto Rican Bad Bunny-considered the face of Latin trap, a booming genre that fuses reggaeton with ele- US/Peruvian musician Tony Succar ments of hip hop from the US south-received the award for Best Urban Album. -

¡Rosalía Reinó En Los Grammy! (Parte 1) (Noviembre 16)

¡Rosalía reinó en los Grammy! (parte 1) (Noviembre 16) ZONA ROSA Cúcuta, sábado 16 de noviembre de 2019 14 Así se vivieron los premios que reconoce lo mejor a la música latina Emocionado, Juanes recibió el premio a Perso- Ricky Martin fue uno de los presentadores de la Alejandro Sanz recibió el premio a la canción na del Año por sus dos décadas de carrera musi- pop con ‘Mi persona favorita’. gala. cal de manos del líder de Metallica, Lars Ulrich. ¡ROSALÍA REINÓ EN LOS GRAMMY! AFP Fotos: LAS VEGAS (AFP) osalía y su disco ‘El LOS COLOMBIANOS GANADORES: mal querer’ arra- Rsaron el jueves en Fonseca: Mejor álbum vocal pop tradicional por ‘Agustín’. un Grammy Latino en el Andrés Cepeda: Mejor álbum tropical tradicional por que sí sonó el reguetón ‘Andrés Cepeda Big Band (En Vivo)’. y retumbó sobre todo un Puerto Candelaria y Juancho Valencia: Mejor álbum de mensaje de protesta por cumbia/vallenato por ‘Yo me llamo cumbia’. la situación política de Samuel Torres y La Nueva Filarmonía: Mejor álbum de varios países latinoameri- música clásica por ‘Regreso’. canos, especialmente en Chile, donde se “tortura, mata y viola”, como escri- bió en su pecho desnudo La gala en Las Vegas ho- favorita’, que hizo la cantante Mon Laferte. menajeó a leyendas de la con Camila Cabello. Rosalía se llevó los gra- música latina como Celia Juan Luis Guerra mófonos latinos a mejor Cruz, Juan Gabriel, Joan terminó con dos ga- álbum, mejor álbum pop Sebastian y Soda Stereo. lardones, al igual que contemporáneo y mejor También incluyó presenta- los puertorriqueños canción urbana, además ciones sorprendentes como Pedro Capó y Kany de los galardones a mejor la de Vicente Fernández con García, y el argentino diseño y mejor ingeniería. -

Singer-Songwriter Category 22 Best Singer-Songwriter Album Mejor Álbum Cantautor Melhor Álbum Cantor Compositor for Solo Artists Or Duos

THE LATIN ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS 20th Latin GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year June 1, 2018 through May 31, 2019 The following information is confidential and is not to be copied, loaned or otherwise distributed. ACADEMIA LATINA DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS DE LA GRABACIÓN, INC. LISTA FINAL DE NOMINACIONES ® 20.a Entrega Anual Del Latin GRAMMY Para grabaciones lanzadas durante el año de elegibilidad 1° de junio del 2018 al 31 de mayo del 2019 La siguiente información es confidencial y no debe ser copiada, prestada o distribuida de ninguna forma. ACADEMIA LATINA DAS ARTES E CIÊNCIAS DA GRAVAÇÃO, INC. LISTA FINAL DOS INDICADOS ® 20.a Entrega Anual Do Latin GRAMMY Para gravações lançadas durante o Ano de Elegibilidade 1° de junho de 2018 a 31 de maio de 2019 As informações aqui contidas são confidenciais e não devem ser copiadas, emprestadas ou distribuídas por nenhum meio. General Field Category 1 Record Of The Year Grabación del Año 6. LA PLATA Gravação do Ano Juanes Featuring Lalo Ebratt Award to the Artist(s), Album Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s), Mauricio Rengifo & Andrés Torres, record producers; and/or Mixer(s), and Mastering Engineer(s) if other than the artist. Mauricio Rengifo & Andrés Torres, recording engineers; Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Álbum, Ingeniero(s) de Josh Gudwin, mixer; Dave Kutch, mastering engineer Grabación, Ingenieros de Mezcla y Masterizadores si es(son) [Universal Music Latino] otro(s) diferente(s) al artista. 7. AUTE CUTURE Prêmio ao(s) Artista(s), Produtor(es) do Álbum, Engenheiro(s) de Gravação Mixagem e Masterização, se outro que não o próprio Rosalía El Guincho & Rosalía, record producers; El Guincho, Artista. -

Singer-Songwriter Category 22 Best Singer-Songwriter Album Mejor Álbum Cantautor Melhor Álbum Cantor Compositor for Solo Artists Or Duos

THE LATIN ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS 20th Latin GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year June 1, 2018 through May 31, 2019 The following information is confidential and is not to be copied, loaned or otherwise distributed. ACADEMIA LATINA DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS DE LA GRABACIÓN, INC. LISTA FINAL DE NOMINACIONES ® 20.a Entrega Anual Del Latin GRAMMY Para grabaciones lanzadas durante el año de elegibilidad 1° de junio del 2018 al 31 de mayo del 2019 La siguiente información es confidencial y no debe ser copiada, prestada o distribuida de ninguna forma. ACADEMIA LATINA DAS ARTES E CIÊNCIAS DA GRAVAÇÃO, INC. LISTA FINAL DOS INDICADOS ® 20.a Entrega Anual Do Latin GRAMMY Para gravações lançadas durante o Ano de Elegibilidade 1° de junho de 2018 a 31 de maio de 2019 As informações aqui contidas são confidenciais e não devem ser copiadas, emprestadas ou distribuídas por nenhum meio. General Field Category 1 Record Of The Year Grabación del Año 6. LA PLATA Gravação do Ano Juanes Featuring Lalo Ebratt Award to the Artist(s), Album Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s), Mauricio Rengifo & Andrés Torres, record producers; and/or Mixer(s), and Mastering Engineer(s) if other than the artist. Mauricio Rengifo & Andrés Torres, recording engineers; Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Álbum, Ingeniero(s) de Josh Gudwin, mixer; Dave Kutch, mastering engineer Grabación, Ingenieros de Mezcla y Masterizadores si es(son) [Universal Music Latino] otro(s) diferente(s) al artista. 7. AUTE CUTURE Prêmio ao(s) Artista(s), Produtor(es) do Álbum, Engenheiro(s) de Gravação Mixagem e Masterização, se outro que não o próprio Rosalía El Guincho & Rosalía, record producers; El Guincho, Artista. -

Catálogo Karaoke

EL KARAOKE DE LAS ESTRELLAS EL KARAOKE DE LAS ESTRELLAS Lista de canciones en Español megasoftkaraoke.online 0991654536 karaokedelasestrellasec CONTACTOS: 099 165 4536 • www.megasoftkaraoke.online 1 EL KARAOKE DE LAS ESTRELLAS 2 CONTACTOS: 099 165 4536 • www.megasoftkaraoke.online EL KARAOKE DE LAS ESTRELLAS ARTISTA TÍTULO GÉNERO COD 100% PURO DINAMITA YO SOY TU MAESTRA CUMBIA 2818 3BALL MTY INTÉNTALO REGGAETÓN 2819 AARON Y SU GRUPO ILUSIÓN DESTILANDO AMOR CUMBIA SONIDERA 3997 ABBA CHIQUITITA BALADA 51 ABEL ROMEO CASTILLO ROMANCE DE MI DESTINO PASILLO 8086 ACÚSTICA AMOR PROHIBIDO BALADA 747 ADOLESCENTES ANHELO SALSA 2427 ADOLESCENTES CUERPO SIN ALMA SALSA 2571 ADOLESCENTES EN AQUEL LUGAR SALSA 2924 ADOLESCENTES HOY APRENDÍ SALSA 4876 ADOLESCENTES PERSONA IDEAL SALSA 1060 ADOLESCENTES SI TE HAS DE MARCHAR SALSA 4877 ADOLESCENTES VIRGEN SALSA 4722 ADRIANA FOSTER PIENSO EN TI BALADA POP 3024 ADRIANA LUCÍA DILO VALLENATO 2743 ADRIANA LUCÍA ENAMÓRATE COMO YO VALLENATO 2925 ADRIANA LUCÍA OLVIDARTE ES IMPOSIBLE VALLENATO 2926 AFROSOUND MAR DE EMOCIONES LAMBADA 4602 AGUILAR Y SU ORQUESTA EL CABAÑAL CUMBIA MANABA 8397 AGUSTÍN LARA PIENSA EN MÍ BOLERO 550 AIDA CUEVAS QUIZÁS MAÑANA RANCHERA 4089 AIDA Y CARLOS CUEVAS RECONCILIACIÓN RANCHERA 4090 ALADINO DIOSA ROCKOLA 8001 ALADINO MUJER BOLERA ROCKOLA 8091 ALADINO PENAS ROCKOLA 8322 ALADINO TU PERFUME BACHATA 8092 ALADINO TÚ TIENES LA CULPA ROCKOLA 8008 ALADINO YA TIENE QUINCE AÑOS ROCKOLA 8051 ALASKA Y DINARAMA A QUIEN LE IMPORTA ROCK LATINO 4343 ALASKA Y DINARAMA COMO PUDISTE HACERME ESTO A MÍ ROCK -

2019 ASCAP Accolades Booklet

ACC OLA DES ASCAP MEMBER ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2019 ASCAP members united our world in 2019. 2019 was another record-breaking, game-changing year for ASCAP members. Their music evolved in magnificent ways, connecting, inspiring, lifting and healing us as only music can. Here’s a look back at some of our members’ most remarkable THE achievements from 2019 and the past decade - a small sampling of the milestones met by our global family of music creators. We’ve also GOLDEN highlighted six ASCAP members from throughout our repertory who experienced breakout years in 2019. AGE Congratulations to ASCAP’s chart-topping, mold-breaking songwriters and composers – and to all of our 740,000 songwriter, composer and music publisher members – for giving us something to sing about. THE GOLDEN AGE BILLIE EILISH & FINNEAS ASCAP superstars honored across the genre spectrum 2020 GRAMMY AWARDS Highlights… logged a sold-out world tour, performed at Coachella and made her Saturday Night Live BILLIE EILISH Best New Artist debut – all with FINNEAS alongside her in her Record of the Year - “Bad Guy” backing band. The accolades kept flowing: Album of the Year - When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? the pair won the ASCAP Vanguard Award Song of the Year - “Bad Guy” in May, and were nominated for a collective Best Pop Vocal Album - When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? 11 Grammys; Eilish also picked up honors at FINNEAS the American Music Awards, Apple Music Producer of the Year, Non-Classical Awards, MTV VMAs, Teen Choice Awards and Record of the Year - “Bad Guy” Album of the Year - When We All Fall Asleep, more. -

Lista De Socios De La Sgae Nominados a Los Latin

LISTA DE SOCIOS DE LA SGAE NOMINADOS A LOS LATIN GRAMMY® 2019 GRABACIÓN DEL AÑO - Verdades afiladas Andrés Calamaro - Kitipun Juan Luis Guerra - Con altura Rosalía y El Guincho - Mi persona favorita Alejandro Sanz - No tengo nada Alejandro Sanz ÁLBUM DEL AÑO - Cargar la suerte Andrés Calamaro - El mal querer El Guincho, Rosalía y Antón Álvarez Alfaro - El disco Alejandro Sanz CANCIÓN DEL AÑO - Kitipun Juan Luis Guerra - Mi persona favorita Alejandro Sanz - No tengo nada Alejandro Sanz - Querer mejor Ricardo Montaner MEJOR NUEVO ARTISTA Aitana MEJOR ÁLBUM VOCAL POP CONTEMPORÁNEO - Montaner Ricardo Montaner - Balas perdidas Morat (Juan Pablo Isaza, Juan Pablo Villamil, Simón y Martín Vargas) 1 - El mal querer Rosalía - El disco Alejandro Sanz MEJOR ÁLBUM VOCAL POP TRADICIONAL - Sentimientos Pavel Nuñez MEJOR CANCIÓN POP - Pienso en tu mirá El Guincho, Rosalía y Antón Álvarez Alfaro - Mi persona favorita Alejandro Sanz MEJOR CANCIÓN URBANA - Con altura El Guincho y Rosalía MEJOR ÁLBUM DE ROCK - MTV Unplugged: El desconecte Molotov (Juan Francisco Ayala, Randy Clifford Ebright Wideman e Ismael Fuentes de Garay) MEJOR ÁLBUM POP/ROCK - Madame Ayahuasca Taburete (Guillermo Bárcenas y Antón Carreño) - Cargar la suerte Andrés Calamaro - Nuclear Leiva MEJOR CANCIÓN DE ROCK - Godzilla (del disco “Nuclear”) Leiva - Verdades afiladas (del disco “Cargar la suerte”) Andrés Calamaro 2 MEJOR ÁLBUM TROPICAL TRADICIONAL - Lo nuestro Yelsy Heredia - Vereda tropical Olga Cerpa y Mestisay MEJOR ÁLBUM CONTEMPORANEO FUSIÓN TROPICAL - Literal Juan Luis Guerra MEJOR CANCIÓN TROPICAL - Kitipun Juan Luis Guerra MEJOR ÁLBUM CANTAUTOR - Acústica Albita MEJOR ÁLBUM INSTRUMENTAL - Saxofones live sessions Cuban Sax Quintet (Germán Velazco, César López, Alfred Thompson y Evaristo Denis) - Unbalanced concerto for ensemble Moisés P. -

AÑO ARTISTA CANCIÓN 1999 Ricky Martin Livin' La Vida Loca Celia Cruz

AÑO ARTISTA CANCIÓN 1999 Ricky Martin Livin' la vida loca Celia Cruz La vida es un carnaval Shakira Ojos así Cher Believe Britney Spears Baby one more time Backstreet Boys I want it that way Lou Bega Mambo N 5 Chayanne Salome Enrique Iglesias Bailamos Lenny Kravitz Fly Away 2000 Britney Spears Oops I did it again La Ley Aquí Madonna Music Christina Aguilera Ven conmigo Robbie Williams Rock DJ Thalía Arrasando Jennifer Lopez Let’s get loud Los Fabulosos Cadillacs Vos sabes Santana ft Maná Corazón espinado U2 Beautiful Day 2001 Chocolate Mayonesa DJ Mendez Fiesta Shakira Suerte Daft Punk One more time Chayanne Boom Boom Cristian Castro Azul Paulina Rubio Y yo sigo aquí Kylie Minogue Can't get you out of my head Pedro Fernández Yo no fui Javiera y los Imposibles Maldita primavera 2002 Juanes A Dios le pido Las Ketchup Aserejé Axé Bahia Beso en la boca Diego Torres Color esperanza Chayanne Torero Robbie Williams Feel Enrique Iglesias Heroe Avril Lavigne Complicated Juanes Es por ti Coldplay Clocks 2003 Juanes Mala gente Maná Mariposa traicionera Bacilos Mi primer millón Julieta Venegas Andar conmigo Beyoncé Crazy in love Black Eyed Peas Where is the love? Alejandro Sanz No es lo mismo Bacilos Caraluna Juanes ft Nelly Furtado Fotografía Jennifer López Jenny from the block 2004 Daddy Yankee Gasolina Daddy Yankee Lo que pasó pasó Maroon 5 This love Calle 13 Atrévete te te Julieta Venegas Lento Vicentico Los caminos de la vida Azúcar Moreno Él Kudai Ya nada queda Cafe Tacvba Eres Franz Ferdinand Take me out 2005 Juanes La camisa negra Shakira -

Advances in Computerized Adaptive Measurement of Personality By

Advances in Computerized Adaptive Measurement of Personality by María Dolores Nieto A doctoral dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Psychology in Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Directors: Dr. Francisco J. Abad and Dr. Luis Eduardo Garrido July 2019 Madrid, Spain 3 This dissertation is in memoriam of Julio Olea. None of this would be possible without him. 5 Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less. MARIE CURIE 7 A la memoria de Julio Olea Gran parte de esta tesis ha sido posible gracias a la constancia e ilusion de Julio Olea (1961-2018), catedrático del Departamento de Psicología Social y Metodología en la Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Aunque son y serán varios los homenajes que se harán en recuerdo de Julio, quisiera que esta tesis conste como mi pequeño homenaje personal a la memoria de mi codirector, el cual por motivos de salud falleció el pasado 1 de octubre del 2018. Julio ha sido uno de los principales impulsores de muchas de las ideas que forman parte de esta tesis desde sus comienzos. En particular, su trabajo en los dos primeros estudios desarrollados, los cuales ya han sido publicados, ha sido fundamental para llevar esta tesis a buen puerto. Pero más allá de las formalidades académicas que se destacarán en otros actos, quisiera recordar mi experencia como doctoranda junto a Julio desde un punto de vista más personal.