PEN Melbournemagazine 2/2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABC Radio Melbourne Announces 2019 Line-Up the 2019 Program

ABC Radio Melbourne announces 2019 line-up The 2019 program year for ABC Radio Melbourne sees fresh voices and long-time favourites return to the airwaves on Monday 21 January. Melbourne will wake up with Jacinta Parsons & Sami Shah from 5.30am – 7.45am, while Mornings icon Jon Faine returns along with the popular Conversation Hour. From 12.30pm – 2pm, expect a great mix of music, art and culture as Myf Warhurst returns. Richelle Hunt will keep you entertained with a fresh take on weekday Afternoons and as co-host of The Friday Revue with the inimitable Brian Nankervis. Walkley-winning journalist Raf Epstein is back behind the wheel of Drive between 4pm - 6.30pm, ahead of current affairs program PM at 6.30pm. Master wordsmith and crossword guru David Astle will present Evenings in 2019, picking up the baton from Lindy Burns, who announced last month that she wouldn’t be returning to the station in 2019 due to family reasons. After ten years presenting Saturday Breakfast and Saturday Mornings, Hilary Harper is moving to a new role at ABC Radio National as host of the flagship social affairs program Life Matters. ABC Radio Melbourne is thrilled to welcome Libbi Gorr as the new voice of Weekends, as she brings her trademark warmth and humour to both Saturday and Sunday Mornings. Nightlife with Philip Clark / Sarah Macdonald and Overnights with Trevor Chappell / Rod Quinn all return in 2019. ABC Radio Melbourne Manager Dina Rosendorff said: “We’re looking forward to consolidating the line-up changes we made last year, bringing depth and distinctiveness to everything we do, connecting with the community and delivering some great listening across the week.” -ENDS- For media inquiries, contact: Kat Lindsay, Marketing Manager, ABC Regional & Local (VIC & TAS), P: (03) 8646 1603 E: [email protected] . -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

The Goose That Laid the Golden Egg?1

The goose that laid the golden egg?1 Pluralists for a referendum (Pluralists) submission to the Federal Parliamentary Enquiry into 457 visas Background - Pluralists’ Press Council complaints 2 Those Australians who have a detailed knowledge of the history of media in this country are aware of the positions taken by the main ‘players’ in the ‘immigration debate’ and the stance taken by various newspapers and journalists, including the Murdoch press ( eg The Australian and The Weekend Australian ), the Fairfax Press and Government media ( eg ABC and SBS). They are aware that there exists a powerful ‘open borders lobby’ (supporters of high or mass immigration) staffed by those on the extreme ‘right’ and the extreme ‘left’, and some who fall in between. It is well known that Rupert Murdoch is a member of, and has been active in, Partnership for a New American Economy , and that he promotes mass immigration to the US, and immigration generally. 3 On a recent trip to Australia, Mr Murdoch (he wields enormous influence over Australian Government policy but does not live here) expressed his support for immigration and the use of 457 visas in Australia in a way that many Australians would interpret as clear support for the open borders lobby, and the view that opposition to open borders policies is largely racist or xenophobic. For many Australians, this would explain why the Murdoch Press is conducting an ‘open borders press campaign’, although its existence, and the influence of ‘the Chairman’, would no doubt be vociferously denied by them. -

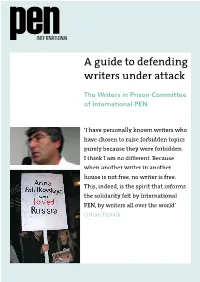

A Guide to Defending Writers Under Attack

A guide to defending writers under attack The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN ‘I have personally known writers who have chosen to raise forbidden topics purely because they were forbidden. I think I am no different. Because when another writer in another house is not free, no writer is free. This, indeed, is the spirit that informs the solidarity felt by International PEN, by writers all over the world’ Orhan Pamuk A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN Contents Introduction 3 Part One: What is International PEN? 6 International PEN Charter 7 Part Two: An introduction to the Writers in Prison Committee 8 How does the Writers in Prison Committee work? 9 Part Three: Joining the Writers in Prison Committee 12 Part Four: Who does the Writers in Prison Committee work for? 14 Case List 15 Part Five: The Writers in Prison Committee Activities & Resources 17 Honorary Members 17 Rapid Action Network 23 Writing Offi cial Appeals 27 Biennial Conferences 32 Campaign and Focus Actions 32 The Day of the Imprisoned Writer & other international days 34 Meetings with Ambassadors and Governments 36 Embassy Visits 37 Visits to your foreign ministry 37 Trial observations and other missions 38 Working with other NGOs 38 Approaching Intergovernmental organisations 38 Working with Writers in Exile 39 PEN Emergency Fund 39 Awards 40 Part Six: Media and Publicity: raising public awareness and infl uencing opinion 40 Part Seven: The Writers in Prison Committee and International PEN 44 Part Eight: Resources and Glossary 47 2 A guide to defending writers under attack: The Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN September 2010 Dear colleagues in International PEN, It is a great pleasure to be able to present to you, at the 76th Congress of International PEN in Tokyo, printed copies of the Writers in Prison Committee’s handbook, A guide to defending writers under attack. -

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference. -

Human Rights in the Twentieth-Century

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY: A LITERARY HISTORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE BY HADJI BAKARA CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iii Introduction: A Century in Four Figures 1 Chapter One: The Legislator 29 Chapter Two: The Refugee 77 Chapter Three: The Prisoner 131 Chapter Four: The Witness 182 Bibliography 240 ii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 | Vladimir Nabokov, American Identification Card (1940) | 1 Figure 2 | Vladimir Nabokov, Index Card Drafts Lolita (undated) | 2 Figure 3 | Archibald MacLeish, Preamble to the United Nations Charter (undated) | 30 Figure 4 | Archibald MacLeish’s “Declaration Draft” detail (undated) | 34 Figure 5 | Archibald MacLeish’s “Declaration Draft” (undated) | 51 Figure 6 | Archibald MacLeish’s draft of the preamble to the UN Charter (1945) | 52 Figure 7 | Archibald MacLeish First Fragment of “Actfive” (1945) | 63 Figure 8 | United Nations Commission on Human Rights. Lake Success, New York (1947) | 65 Figure 9 | Peter Benenson, “The Forgotten Prisoners,” May 28th, 1961 | 133 Figure 10 | “Freedom Writers.” Amnesty Campaign (1988) | 136 Figure 11 | PEN International Campaign Poster Jen Saro Wiwa (1994) | 137 Figure 13 | Heinemann edition of Ngugi’s Detained (1981) | 143 Figure 14 | Paul Tabori, Book Cover for The Pen in Exile (1954) | 145 Figure 15 | Paul Tabori, List of imprisoned writers (1960) | 147 Figure 16 | Agostinho Neto (1968) | 148 Figure 17 | Spanish Edition of Henri Alleg’s La Question (1957) | 157 Figure 18 | Ernesto Sabato delivers first drafts of Nunca Mas (1984) | 163 Figure 19 | Gabriel Garcia Marquez at the Russell War Crimes Tribunals II (1974) | 164 Note: Actual images not included in this version of the dissertation due to copyright issues. -

The PEN International Stage & Screen Circle

‘PEN International has traditionally been a place where great artists of stage and screen -Thornton Wilder, Maurice Maeterlinck, Arthur Miller, Ronald Harwood, Octavio Paz and Harold Pinter- have fought for freedom of expression the world over. Today, as even a mobile phone can be a movie camera, we are able to bear witness to human rights violations as never before. In these times, more than ever, PEN defends playwrights, screenwriters and filmmakers who are censored, silenced and jailed’ – JENNIFER CLEMENT, PEN INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT ‘I consider freedom of expression the most important cause that PEN supports. Without freedom of expression we are lost’ – RONALD HARWOOD, PEN INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT EMERITUS ‘My respect for this organisation has no borders…PEN has been so fierce, so consistent and ferocious in its efforts that it is hard to ignore their worldwide impact.’ The PEN – TONI MORRISON, PEN INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT International For more information contact [email protected] Stage & Screen Cover image: PEN International President Emeritus Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe arrive in London for the premier of film The Prince and the Showgirl with Laurence Olivier. Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images. PEN International is a registered UK charity under the name International P. E. N. Circle Our charity number is 1117088. Who Stage and We Are Screen Circle Although PEN’s membership has always included advocates from the stage and PEN International and the stage and screen worlds have been interwined for almost screen, we are also increasingly fighting for the freedom of playwrights, directors and one hundered years. One of PEN’s founding members, along with H.G Wells, was screenwriters: George Bernard Shaw. -

Black Saturday, 10 Years on Coverage on ABC Radio Melbourne

For immediate release 4 February 2019 Black Saturday, 10 Years On Coverage on ABC Radio Melbourne On Wednesday 6 February, ABC Radio Melbourne will mark the 10th anniversary of the 2009 fires with a full day of live broadcasts across the state. The programs will revisit the stories of the people who survived this extraordinary traumatic event and highlight the rebuilding and recovery process still taking place within communities today. ABC Radio Melbourne manager Dina Rosendorff says, “This special day of programming is part of ABC Radio’s ongoing commitment to emergency broadcasting, where we educate and inform our community of dangers and risks to encourage better preparation for future fires; and continue to support fire affected communities and individuals by telling their stories. “Listeners are encouraged to tune-in or come along to these broadcasts across the day as we highlight the extraordinary resilience of the communities affected and share the highs and lows 10 years on,” concluded Dina. Event Details: • Breakfast, 5.30 – 7.45am: Marysville, Rotunda in the park – All Welcome Jacinta Parsons and Sami Shah invite you to join them from Marysville as they start the day of live broadcasts. • Mornings, 8.30 – 12 noon: Strathewen Primary School – All Welcome Jon Faine will revisit the community from Strathewen and their rebuilt local Primary School. • Myf Warhurst program, presented by Meshel Laurie: Melbourne Museum Melbourne Museum’s commemorative activation From The Heart presents personal stories behind 12 objects from the state bushfire collection, a Tree of Remembrance, and a series of photographs on loan from Department of Environment, Land and Water Protection. -

Pen International Writers in Prison Committee Caselist

PEN INTERNATIONAL WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE CASELIST January-December 2013 PEN International Writers in Prison Committee 50/51 High Holborn London WC1V 6ER United Kingdom Tel: + 44 020 74050338 Fax: + 44 020 74050339 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.pen-international.org PEN INTERNATIONAL CHARTER The P.E.N. Charter is based on resolutions passed at its International Congresses and may be summarised as follows: P.E.N. affirms that: 1. Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. 2. In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion. 3. Members of P.E.N. should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. 4. P.E.N. stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. P.E.N. declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. -

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter's Plays

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter’s Plays through the Lens of Arabic Plays from Egypt and Syria Hekmat Shammout A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine how far the political plays of Harold Pinter reflect the Arabic political situation, particularly in Syria and Egypt, by comparing them to several plays that have been written in these two countries after 1967. During the research, the comparative study examined the similarities and differences on a theoretical basis, and how each playwright dramatised the topic of political violence and aggression against oppressed individuals. It also focussed on what dramatic techniques have been used in the plays. The thesis also tries to shed light on how Arab theatre practitioners managed to adapt Pinter’s plays to overcome the cultural-specific elements and the foreignness of the text to bring the play closer to the understanding of the targeted audience. -

Investing in Audiences – ABC Annual Report 2017 – Volume 1

INVESTING IN VOLUME I AUDIENCES ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Gordon Churchill as Maki in The Warriors Australian Broadcasting Corporation New South Wales – Ultimo ABC Ultimo Centre New South Wales – Ultimo 700 Harris Street, Ultimo NSW 2007 GPO Box 9994, Sydney NSW 2001 Tel. +61 2 8333 1500 abc.net.au ABC Ultimo Centre 700 Harris Street Ultimo NSW 2007 GPO Box 9994 Sydney NSW 2001 Tel. +61 2 8333 1500 abc.net.au 6 October 2017 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for Communications and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present the Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2017. The Report is prepared in accordance with the requirements of Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983, and was approved by a resolution of the Board on 25 September 2017. It provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance in relation to its legislative mandate and against the backdrop of the seismic change in the media sector. The editorial theme of this year’s report – Investing In Audiences – demonstrates the absolute focus of the Corporation on delivering outstanding services and programming. In line with its Charter remit, the ABC is committed to maximising its investment in quality content across its platforms and programs, ensuring that we are part of the lives of all Australians. This is how we repay the community for the loyalty and trust it places in the national broadcaster. Yours sincerely Justin Milne Chairman i We make content for all Australians, about all Australians. -

PEN International Impact and Learning Report 2015 to 2019

PEN INTERNATIONAL IMPACT AND LEARNING REPORT 2015 - 2019 On the Frontline Defending Freedom of Expression and Promoting Literature Cover image: During PEN International Congress in Pune, India in 2018, delegates joined local students on a public wari travelling three kilometres over three hours in celebration of global languages. PEN is grateful to its many Overview 1 individual supporters and volunteers who make its 2015 to 2019 work possible including Swedish International 13 Development Cooperation Supporting Agency (Sida), PEN Writers at Risk Publishers, Writers and Readers Circles, International Cities of Refuge Network Challenging 29 (ICORN), the Norwegian Structural Threats Ministry of Foreign Affairs, United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF), Clifford Strengthening 40 Chance, Fritt Ord and Evan Civil Society Cornish Foundation 55 PEN International Looking forward: Unit A - Koops Mill Mews 162-164 Abbey Street London SE1 2AN PEN International United Kingdom PEN International promotes literature and freedom of 2020 to 2023 expression and is governedby the PEN Charter and the principles it embodies: unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations. Founded in 1921, PEN International connects an international community of writers from its Secretariat in London. It is a forum where writers meet freely to discuss their work; it is also a voice speaking out for writers silenced in their own countries. Through Centres in over 100 countries, PEN operates on five continents. PEN International is a non-political organisation which holds Special Consultative Status at the UN and Associate Status at UNESCO. International PEN is a registered charity in England and Wales with registration number 1117088.