Tasmanian College of the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Ways of Seeing': the Tasmanian Landscape in Literature

THE TERRITORY OF TRUTH and ‘WAYS OF SEEING’: THE TASMANIAN LANDSCAPE IN LITERATURE ANNA DONALD (19449666) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2013 ii iii ABSTRACT The Territory of Truth examines the ‘need for place’ in humans and the roads by which people travel to find or construct that place, suggesting also what may happen to those who do not find a ‘place’. The novel shares a concern with the function of landscape and place in relation to concepts of identity and belonging: it considers the forces at work upon an individual when they move through differing landscapes and what it might be about those landscapes which attracts or repels. The novel explores interior feelings such as loss, loneliness, and fulfilment, and the ways in which identity is derived from personal, especially familial, relationships Set in Tasmania and Britain, the novel is narrated as a ‘voice play’ in which each character speaks from their ‘way of seeing’, their ‘truth’. This form of narrative was chosen because of the way stories, often those told to us, find a place in our memory: being part of the oral narrative of family, they affect our sense of self and our identity. The Territory of Truth suggests that identity is linked to a sense of self- worth and a belief that one ‘fits’ in to society. The characters demonstrate the ‘four ways of seeing’ as discussed in the exegesis. ‘“Ways of Seeing”: The Tasmanian Landscape in Literature’ considers the way humans identify with ‘place’, drawing on the ideas and theories of critics and commentators such as Edward Relph, Yi-fu Tuan, Roslynn Haynes, Richard Rossiter, Bruce Bennett, and Graham Huggan. -

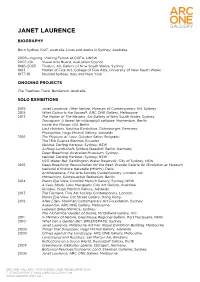

Janet Laurence

JANET LAURENCE BIOGRAPHY Born Sydney 1947, Australia. Lives and works in Sydney, Australia. 2008–ongoing Visiting Fellow at COFA, UNSW 2007–09 Visual Arts Board, Australian Council 1996–2005 Trustee, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1993 Master of Fine Art, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales 1977–81 Studied Sydney, Italy and New York ONGOING PROJECTS The Treelines Track, Bundanon, Australia. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Janet Laurence: After Nature, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney 2018 What Colour is the Sacred?, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne 2017 The Matter of The Masters, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Transplant: A forest for chlorophyll collapse, Momentum, Berlin Inside the Flower, IGA Berlin Lost Habitats, Nautilus Exhibition, Oldenburger, Germany Phytophilia, Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide 2016 The Pleasure of Love, October Salon, Belgrade The 13th Cuenca Biennial, Ecuador Habitat, Darling Harbour, Sydney, NSW Auftrag Landschaft, Schloss Biesdorf, Berlin, Germany Deep Breathing, Australian Musueum, Sydney. Habitat, Darling Harbour, Sydney, NSW H2O Water Bar, Paddington Water Reservoir, City of Sydney, NSW 2015 Deep Breathing: Resuscitation for the Reef, Grande Galerie de l’Evolution at Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Paris. Antrhopocene, Fine Arts Society Contemporary, London, UK Momentum, Kuntsquartier Bethanien, Berlin 2014 Plants Eye View, Dominik Mersch Gallery, Sydney, NSW. A Case Study, Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, Austrlaia. Residue, Hugo Mitchell Gallery, Adelaide. 2013 The Ferment, Fine Art Society Contemporary, London. Plants Eye View, Cat Street Gallery, Hong Kong. 2012 After Eden, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney. Avalanche, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne. Fabeled, BREENSPACE, Sydney. The Alchemical Garden of Desire, McClelland Gallery, VIC. -

Captain Louis De Freycinet

*Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 1 CAPTAIN LOUIS DE FREYCINET AND HIS VOYAGES TO THE TERRES AUSTRALES *Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 3 HORDERN HOUSE rare books • manuscripts • paintings • prints 77 VICTORIA STREET POTTS POINT NSW 2011 AUSTRALIA TEL (61-2) 9356 4411 FAX (61-2) 9357 3635 [email protected] www.hordern.com CONTENTS Introduction I. The voyage of the Géographe and the Naturaliste under Nicolas Baudin (1800-1804) Brief history of the voyage a. Baudin and Flinders: the official narratives 1-3 b. The voyage, its people and its narrative 4-29 c. Freycinet’s Australian cartography 30-37 d. Images, chiefly by Nicolas Petit 38-50 II. The voyage of the Uranie under Louis de Freycinet (1817-1820) Brief history of the voyage a. Freycinet and King: the official narratives 51-54 b. Preparations and the voyage 55-70 c. Freycinet constructs the narrative 71-78 d. Images of the voyage and the artist Arago’s narrative 79-92 Appendix 1: The main characters Appendix 2: The ships Appendix 3: Publishing details of the Baudin account Appendix 4: Publishing details of the Freycinet account References Index Illustrated above: detail of Freycinet’s sketch for the Baudin atlas (catalogue no. 31) Illustrated overleaf: map of Australia from the Baudin voyage (catalogue no. 1) INTRODUCTION e offer for sale here an important on the contents page). To illuminate with knowledge collection of printed and original was the avowed aim of each of the two expeditions: Wmanuscript and pictorial material knowledge in the widest sense, encompassing relating to two great French expeditions to Australia, geographical, scientific, technical, anthropological, the 1800 voyage under Captain Nicolas Baudin and zoological, social, historical, and philosophical the 1817 voyage of Captain Louis-Claude de Saulces discoveries. -

Tasmania History, Art & Landscape Featuring the Glover Prize

TASMANIA HISTORY, ART & LANDSCAPE FEATURING THE GLOVER PRIZE MARCH 4-11, 2021 TOUR LEADER: ROBERT VEEL TASMANIA Overview HISTORY,\ ART & LANDSCAPE Tasmania has a distinctive history, culture and landscape which makes it quite different from Australia’s other states and territories. This tour offers Tour dates: March 4-11, 2021 a unique itinerary which combines the island’s well-known attractions with sites of particular interest to travellers with a strong interest in history and Tour leader: Robert Veel the arts. Staying in Launceston, Freycinet and Hobart, with day trips to surrounding areas, we visit historic homes and gardens and travel though Tour Price: $4,895 per person, twin share stunning landscapes. Art lovers are well catered for, with an in-depth look at colonial artist John Glover including the platinum access to the opening Single Supplement: $1,090 for sole use of night cocktail party and prize giving ceremony of the annual Glover Prize double room (subject to availability), and a visit to the renowned Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) on the Derwent River near Hobart. Booking deposit: $1000 per person Tasmania was one of the first places to be settled, and this is reflected in Recommended airline: Qantas or Virgin the fine early colonial architecture, with many towns and homesteads dating from the 1830s and 40s. It was also a place of social Maximum places: 20 experimentation in the 1800s, when convicts were sent from England to be improved in Tasmania as artisans, farmers and craftspeople. Side by side with this experimentation was the absolute inhumanity of places like Itinerary: Launceston (3 nights), Freycinet Macquarie Harbour. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 483:117

Vol. 483: 117–131, 2013 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 30 doi: 10.3354/meps10261 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Variation in the morphology, reproduction and development of the habitat-forming kelp Ecklonia radiata with changing temperature and nutrients Christopher J. T. Mabin1,*, Paul E. Gribben2, Andrew Fischer1, Jeffrey T. Wright1 1National Centre for Marine Conservation and Resource Sustainability (NCMCRS), Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Tasmania 7250, Australia 2Biodiversity Research Group, Climate Change Cluster, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2007, Australia ABSTRACT: Increasing ocean temperatures are a threat to kelp forests in several regions of the world. In this study, we examined how changes in ocean temperature and associated nitrate concentrations driven by the strengthening of the East Australian Current (EAC) will influence the morphology, reproduction and development of the widespread kelp Ecklonia radiata in south- eastern Australia. E. radiata morphology and reproduction were examined at sites in New South Wales (NSW) and Tasmania, where sea surface temperature differs by ~5°C, and a laboratory experiment was conducted to test the interactive effects of temperature and nutrients on E. radiata development. E. radiata size and amount of reproductive tissue were generally greater in the cooler waters of Tasmania compared to NSW. Importantly, one morphological trait (lamina length) was a strong predictor of the amount of reproductive tissue, suggesting that morphological changes in response to increased temperature may influence reproductive capacity in E. radiata. Growth of gametophytes was optimum between 15 and 22°C and decreased by >50% above 22°C. Microscopic sporophytes were also largest between 15 and 22°C, but no sporophytes developed above 22°C, highlighting a potentially critical upper temperature threshold for E. -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

Curriculum Vitae MARK RODDA

Curriculum Vitae MARK RODDA EDUCATION 1999 Bachelor of Arts (Fine Art) (Honours), Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology 1994 Bachelor of Fine Art (Painting), University of Tasmania, Launceston SOLO EXHIBITION 2017 Ephemeral Archipelago, Estuary Lookout, Gallery 9, Sydney 2015 Flora with Fauna, Gallery 9, Sydney 2015 Nature vs Nurture, Sanderson Contemporary, Auckland 2014 Lairs of the Haunted, Utopian Slumps, Melbourne 2013 Shoeglaze, Gallery 9, Sydney 2012 Autumn Landscapes, Utopian Slumps, Melbourne 2011 Mark Rodda + Jake Walker, Utopian Slumps stall, Auckland Art Fair 2011 Sleeping Giants, Utopian Slumps, Melbourne 2010 Tidal River, 24hr Art, NT Centre for Contemporary Art, Darwin 2010 Phantom Lords, Seventh, Melbourne 2009 Tidal River, Kings ARI, Melbourne 2008 True Game Systems, (in collaboration with Utopian Slumps and Buro North), Next Wave Festival, Federation Square, Melbourne 2007 The Inland Sea (with Jake Walker), Utopian Slumps, Melbourne 2007 Under A Tungsten Star, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne 2007 Four Short Films, Video Lounge, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney 2005 Monsters & Their Treasure, Bus, Melbourne 2005 Fortress, Westspace Inc. Melbourne 2004 New Instruction in Lawlessness, Tcb inc art, Melbourne 2004 Evil Twin, Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts, Melbourne 2002 2D Game Scenarios, Mass gallery, Melbourne 1995 Deliberate Mistakes and Planned Spontaneity Gallery Two, Launceston GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 Tom Crago’s Materials, (contributing artist), NGV Triennial, Melbourne 2017 Stockroom -

R-M-Mcgivern-Catalogue-2019.Pdf

23 November 2019 to 1 February 2020 ii Nicholas Aplin Kate Beynon Amber Boardman Angela Brennan Janet Burchill Dord Burrough Penelope Cain Hamish Carr Kevin Chin Nadine Christensen Dale Cox Nicola Dickson Fernando do Campo Briell Ellison Josh Foley Juan Ford Betra Fraval Deanne Gilson Helga Groves Stephen Haley Katherine Hattam Euan Heng Sophia Hewson Miles Howard-Wilks Deborah Klein Kate Kurucz Emma Lindsay Tony Lloyd Dane Lovett Simon MacEwan Jordan Marani Sam Martin Andrew Mezei Luke Pither Kenny Pittock Victoria Reichelt Mark Rodda Evangelos Sakaris Kate Shaw Shannon Smiley Julian Aubrey Smith Jacqui Stockdale Camilla Tadich Jelena Telecki Sarah Tomasetti Message from Maroondah City Councillors The inaugural R & M McGivern Prize was held in 2003 and since this time has grown to become a prestigious national painting prize attracting artists from all over the country. Well-regarded Australian artists such as Martin King, Rose Nolan and Rosslynd Piggott have each been significant recipients of this award. Submissions to the R & M McGivern Prize this year were of outstanding range and quality, with a record number of 450 entries. Thank you to all of the artists who entered. We are honoured to have three distinguished judges for this year’s prize: Charlotte Day, Director, Monash University Museum of Art; Ryan Johnston, Director, Buxton Contemporary; Penny Teale, Bunjil Place Gallery Curator. The winning recipient of the Prize receives $25,000, and the work is acquired by Council to become part of the Maroondah City Council Art Collection. This is a distinguished collection maintained by Council for the enjoyment of the Maroondah community and wider audiences. -

Iconic Lands: Wilderness As a Reservation Criterion for World Heritage

ICONIC LANDS Wilderness as a reservation criterion for World Heritage Mario Gabriele Roberto Rimini A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Environmental Studies University of New South Wales April 2010 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude goes to the Director of the Institute of Environmental Studies, John Merson, for the knowledge and passion he shared with me and for his trust, and to the precious advice and constant support of my co-supervisor, Stephen Fortescue. My family, their help and faith, have made this achievement possible. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….…...…… 8 Scope and Rationale.………………………………………………………………………….…...…………. 8 Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Methodology…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Structure…………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 23 CHAPTER II The Wilderness Idea ……………………………………………………………………........ 27 Early conceptions …………………………………………………………………………………………..... 27 American Wilderness: a world model …………………………………………………….....………………. 33 The Wilderness Act: from ideal to conservation paradigm …………………………………........…………. 43 The values of wilderness ……………………………………………………………………….…………… 48 Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………….…………. 58 CHAPTER III Wilderness as a conservation and land management category worldwide …………......... 61 The US model: wilderness legislation in Canada, New Zealand and Australia …………………………… 61 Canada: a wilderness giant ………………………………………………………………………..…........... -

Friends of Tasman Island Newsletter

1 FRIENDS OF TASMAN ISLAND NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2012 No 10 A few words from the President to commemorate the Sesqui centenary of Thinking of Xmas presents? It’s that time of the Tasmania. Delivering the mail to Tasman Island year already! The 2013 Lighthouses of Tasmania footage is about 17 minutes in. calendar is now on sale. This year stunning images http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_ of lighthouses at the Iron Pot, Tasman and Deal detailpage&v=Ds0HCTNxl4w Islands, Eddystone Point, Low Head, Mersey Bluff, Table Cape, Cape Sorell, Cape Tourville I hope you enjoy the last FoTI newsletter for and Rocky Cape. 2012 which also features some history of the Thanks to sponsorship from the Cascade island, albeit on slightly less serious notes Brewery Company, Australian Maritime Systems but equally informative! As always thanks to and Tasmania 40o South, the Lighthouses Dee for design and layout. And thanks to our of Tasmania calendar is our major annual contributors: Mike Jenner, Leslie Johnston fundraiser. For only $20 + postage you can (courtesy Elaine Bell), Karl Rowbottom, Bob and purchase this magnificent, limited edition Penny Tyson, Chris Creese and Erika. Please calendar and know that you are helping to contact FoTI if you have a story you would like to support ongoing work on Tasman Island! share about Tasman Island. Special mention also to our hardworking Have a safe and happy summer break and may Calendar Committee, particularly Erika Shankley 2013 shine for all of us. for another captivating foreword and interesting captions and the many hours she spent along Carol Jackson with Tim Kingston and Pat Murray in the FoTI President selection of the images. -

The Art of Elizabeth Quay, MRA, Perth

• • • • THE ART OF • ELIZABETH • QUAY • • 1 6 / Penny Bovell 9 / The Deadly Dozen: Aurora Abraham, Rod Collard, James Egan, Sandra Egan, Sharyn Egan, Peter Farmer II, Peter Farmer III, Kylie Graham, Biara Martin, Cheryl Martin, John Walley & Theresa Walley 13 / Christian de Vietri 16 / Pamela Gaunt 19 / Simon Gauntlett & Matthew Ngui 22 / Stuart Green 25 / Sandra Hill & Jenny Dawson 28 / Eveline Kotai 31 / Laurel Nannup 35 / Anne Neil in collaboration with Dr Richard Walley & John Walley 38 / Jon Tarry. 2 The contribution Noongar artists have made to Elizabeth Quay Artists view the with both permanent and temporary artworks is especially world differently. meaningful and welcome. A unique partnership between the MRA and the Whadjuk people – the traditional owners of the Derbal Yerrigan (Swan River) and of the land on which Elizabeth Quay sits - presented an opportunity for cultural authenticity. Artists create visual experiences that intrigue, inspire, amuse and It was clear to the MRA at a very early stage of development perhaps even confuse, but which are never humdrum. Outside that the prominent position and high use of Elizabeth Quay of galleries, in the public realm they can influence urban design would provide the perfect opportunity to share Noongar history in surprising ways, making thought provoking artworks that and culture with the wider community. creatively activate space. Public art is intended to generate interaction. The success of This book is a glimpse into the world of each of the artists the Elizabeth Quay artworks can be measured at least in part who designed or made artworks for Elizabeth Quay, the highly by the constant flow of ‘selfies’ being taken around all of them, visible and popular waterfront development that connects and the obvious joy of children having fun with artworks in play Perth city with the Swan River. -

Nowhere Else on Earth

Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values Environment Tasmania is a not-for-profit conservation council dedicated to the protection, conservation and rehabilitation of Tasmania’s natural environment. Australia’s youngest conservation council, Environment Tasmania was established in 2006 and is a peak body representing over 20 Tasmanian environment groups. Prepared for Environment Tasmania by Dr Karen Parsons of Aquenal Pty Ltd. Report citation: Parsons, K. E. (2011) Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values. Report for Environment Tasmania. Aquenal, Tasmania. ISBN: 978-0-646-56647-4 Graphic Design: onetonnegraphic www.onetonnegraphic.com.au Online: Visit the Environment Tasmania website at: www.et.org.au or Ocean Planet online at www.oceanplanet.org.au Partners: With thanks to the The Wilderness Society Inc for their financial support through the WildCountry Small Grants Program, and to NRM North and NRM South. Front Cover: Gorgonian fan with diver (Photograph: © Geoff Rollins). 2 Waterfall Bay cave (Photograph: © Jon Bryan). Acknowledgements The following people are thanked for their assistance The majority of the photographs in the report were with the compilation of this report: Neville Barrett of the generously provided by Graham Edgar, while the following Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the additional contributors are also acknowledged: Neville University of Tasmania for providing information on key Barrett, Jane Elek, Sue Wragge, Chris Black, Jon Bryan, features of Tasmania’s marine