Bor N to Bo X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fight Record Tom Mccormick (Dundalk)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Tom McCormick (Dundalk) Active: 1911-1915 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 53 contests (won: 42 lost: 9 drew: 2) Fight Record 1911 Private Walker WRSF1 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Bill Mansell (Hounslow) WRSF3 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Albert Bayton (Sheffield) WRSF2 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Apr 6 Pte. O'Keefe (Essex Regt) WRTD2(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 613, 614 and 616 (Inter-Allied Lightweight competition 1st series) Apr 8 Seaman Gray (HMS Formidable) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 613, 614 and 616 (Inter-Allied Lightweight competition 3rd series) Apr 10 Seaman White (HMS Patrol) WKO(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 611 and 612 (Inter-Services Lightweight competition semi-final) Apr 10 Sapper Jack O'Neill (Gloucester) LPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 611 and 612 (Inter-Services Lightweight competition final) Oct 18 Pte. Teale (Hussars) WPTS(3) Portsmouth Source: Boxing 28/10/1911 (Army and Navy Welterweight Championship 1st series) Oct 19 Cpl. Hutton (Stratford) LPTS(3) Portsmouth Source: Boxing 28/10/1911 (Army and Navy Welterweight Championship 2nd series) 1912 Jan 15 Bill Mansell (Hounslow) WRSF3(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 20/01/1912 page 291 Jan 20 Cpl. Hutton (Stratford) WRSF6(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 27/01/1912 pages 320, 321 and 322 Referee: B Meadows Jan 24 Charlie Milestone (Chester) WPTS(15) Manchester Regt. -

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre Lewisham Library, 199-201 Lewisham High Street, London SE13 6LG The following items were received from Mrs Gillian Lindsay: Introduction W. (William) Howard Robinson was a noted representative artist and portrait painter of the early twentieth century. He was born on 3 November 1864 in Inverness-shire and attended Dulwich College from 1876 to 1882. He followed his father, William Robinson, into the Law and after a brief legal career studied Art at the Slade School under Sir Simeon Solomon. His professional career as a portrait painter began circa 1910 when his interest in the sport of fencing led him to sketch all the leading fencers of the day, these sketches were reproduced in the sporting publication “The Field” leading to further commissions for portraits with a sporting theme. He became well-known for his sketches and portraits of figures in the sporting world such as Lord Lonsdale, Chairman of the National Sporting Club. His two best known paintings were “An Evening at the National Sporting Club” (1918) and “A Welsh Victory at the National Sporting Club” (1922). This first painting was of the boxing match between Jim Driscoll and Joe Bowker, it took Robinson four years to complete and contained details of 329 sporting celebrities. The second painting commemorated the historic boxing match between Jimmy Wilde and Joe Lynch that took place on 31 March 1919 and shows the Prince of Wales entering the ring to congratulate the victor, the first time that a member of the royal family had done so. -

Fight Record Tom Thomas (Wales)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Tom Thomas (Wales) Active: 1905-1911 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 22 contests (won: 20 lost: 2) Fight Record 1905 Jan 28 Harry Shearing (Walthamstow) WKO3(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Jul 22 Seaman Dunstan (Portsmouth) WRTD3(15) Queens Street Hall, Cardiff Source: Mirror of Life (Welsh Middleweight Title) Referee: JT Hulls combined purse £50 £25 a side Dunstan described as Navy Middle Champion - 4oz gloves 1906 Feb 24 Billy Edwards (Australia) WKO3(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Referee: JT Hulls junior Promoter: Harry Jacobs Mar 31 Bill Cockayne (Kentish Town) WRTD2(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Referee: Brummy Meadows Promoter: Harry Jacobs Apr 9 Pte. Casling (Grenadier Gds.) WKO1(10) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life Referee: JH Douglas Apr 26 P.O. Jim McDonald (RN) WRTD2(6) Tower, London Source: Sporting Life McDonald Navy Champion in 1905 and 1906 May 28 Pat O'Keefe (Canning Town) WPTS(20) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life O'Keefe was British Middleweight Champion 1906 and 1914-16 and 1918-19. Referee: JH Douglas 1908 Apr 30 Mike Crawley (Limehouse) WKO5(10) West End School of Arms, Marylebone Source: Sporting Life Referee: HG Mankin Jun 1 Tiger Smith (Merthyr) WKO4(20) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (British Middleweight Title) -

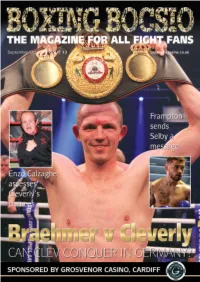

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

Fight Record Young Joseph

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Young Joseph (Aldgate) Active: 1903-1914 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 108 contests (won: 69 lost: 20 drew: 18 other: 1) Fight Record 1903 Nov 28 Darkey Haley (Leytonstone) DRAW(8) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Record Book 1910 Dec 14 Darkey Haley (Leytonstone) WPTS(10) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Record Book 1910 1905 Jan 23 Bert Adams (Spitalfields) W Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Mirror of Life (9st 2lbs competition 1st series) Mar 6 Dick Lee (Kentish Town) WPTS(10) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life (9st 2lbs competition final) Referee: Victor Mansell Mar 20 Alf Reed (Canning Town) WPTS(10) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life Referee: JH Douglas Apr 8 Johnny Summers (Canning Town) WPTS(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Summers was British Featherweight Champion claimant 1906 and British Lightweight Champion 1908-09 and British and British Empire Welterweight Champion 1912-14. Referee: Lionel Draper May 1 Joe Fletcher (Camberwell) DRAW(15) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life Match made at 9st 8lbs Joseph 9st 8lbs Fletcher 9st 7lbs Referee: JH Douglas £50 a side May 27 Alf Reed (Canning Town) DRAW(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Referee: Lionel Draper Promoter: Harry Jacobs and Jack Woolf Jul 15 George Moore (Barking) DRAW(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Mirror of Life Referee: Joe Minden Aug 5 Seaman Arthur Hayes (Hoxton) WPTS(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Mirror of Life Hayes boxed for the British Featherweight Title 1910. -

Fight Record Jim Sullivan (Bermondsey)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Jim Sullivan (Bermondsey) Active: 1901-1920 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 70 contests (won: 46 lost: 17 drew: 7) Fight Record 1901 Dec 2 Billy Gordon (USA) WRTD2(10) Ginnetts Circus, Newcastle Source: Newcastle Daily Journal 1904 Dec 31 Tom Hackett (Bermondsey) WKO2(4) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Mirror of Life (9st 6lbs novice competition semi-final) Referee: Dave Finsberg Promoter: Harry Jacobs 1905 Jan 7 Bill Mansell (Hounslow) LRTD1(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Mirror of Life (9st 6lbs novice competition final) Promoter: Harry Jacobs May 1 Pte. Spain (Irish Gds.) WRTD1(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (10st 8lbs novice competition 1st series) Referee: JH Douglas May 8 Fred Blackwell (Drury Lane) WRTD2(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (10st 8lbs novice competition semi-final) Referee: JH Douglas May 8 Tom Slater (Southwark) WKO1(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (10st 8lbs novice competition 2nd series) Referee: JH Douglas May 8 Jim Jackson (Kentish Town) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (10st 8lbs novice competition final) Referee: JH Douglas 1906 Feb 1 Bill Shettle (Wandsworth) WRSF2(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (10st 4lbs novice competition 2nd series) Referee: Tom Scott Feb 1 Tom Slattery (Blackfriars) -

BOXING the BOUNDARIES: Prize Fighting, Masculinities, and Shifting Social and Cultural Boundaries in the United State, 1882-1913

BOXING THE BOUNDARIES: Prize Fighting, Masculinities, and Shifting Social and Cultural Boundaries in the United State, 1882-1913 BY C2010 Jeonguk Kim Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________ Chairperson __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ Date defended: ___July 8__2010_________ The Dissertation Committee for Jeonguk Kim certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BOXING THE BOUNDARIES: Prize Fighting, Masculinities, and Shifting Social and Cultural Boundaries in the United States, 1882-1913 Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Date defended: _______________________ ii Abstract Leisure and sports are recently developed research topics. My dissertation illuminates the social meaning of prize fighting between 1882 and 1913 considering interactions between culture and power relations. My dissertation understands prize fighting as a cultural text, structured in conjunction with social relations and power struggles. In so doing, the dissertation details how agents used a sport to construct, reinforce, blur, multiply, and shift social and cultural boundaries for the construction of group identities and how their signifying -

Fight Record Harry Reeve

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Harry Reeve (Plaistow) Active: 1910-1934 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 167 contests (won: 90 lost: 53 drew: 22 other: 2) Fight Record 1910 Sep 22 Spike Wallis WKO1(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 01/10/1910 page 752 (9st 4lbs novice competition 1st series) Sep 24 Harry Selleg (Peckham) W(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 01/10/1910 page 752 (9st 4lbs novice competition 2nd series) Oct 1 Pte. Saunders (Royal Irish Rifles) W(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 08/10/1910 page 774 (9st 4lbs competition 3rd series) Oct 13 Harry French (Spitalfields) WRSF1(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 22/10/1910 page 817 (9st 4lbs novice competition semi-final) Oct 15 Young Riley (Haggerston) LRSF6(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 22/10/1910 pages 817 and 821 (9st 4lbs novice competition final) Nov Dick Cartwright (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Record published in Boxing News in the 1960s Nov Bill Bennett (Dublin) WRSF2 The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Record published in Boxing News in the 1960s 1911 Tom Leary (Woolwich) LPTS Source: Brian Strickland (Boxing Historian) Fred Davidson DRAW Source: Brian Strickland (Boxing Historian) Jan 14 Mark Barrett (Lambeth) WRTD4(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 21/01/1911 page 303 Mar 13 Dick Cartwright (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 18/03/1911 pages 498 and 499 May -

The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information I

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information i The Cambridge Companion to Boxing While humans have used their hands to engage in combat since the dawn of man, boxing originated in ancient Greece as an Olympic event. It is one of the most popular, controversial, and misunderstood sports in the world. For its advocates, it is a heroic expression of unfettered individualism. For its critics, it is a depraved and ruthless physical and commercial exploitation of mostly poor young men. This Companion offers engaging and informative chapters about the social impact and historical importance of the sport of boxing. It includes a comprehensive chronology of the sport, listing all the important events and per- sonalities. Chapters examine topics such as women in boxing, boxing and the rise of television, boxing in Africa, boxing and literature, and boxing and Hollywood fi lms. A unique book for scholars and fans alike, this Companion explores the sport from its inception in ancient Greece to the death of its most celebrated fi gure, Muhammad Ali. Gerald Early is Professor of English and African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. He has written about boxing since the early 1980s. His book, The Culture of Bruising , won the 1994 National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. He also edited The Muhammad Ali Reader and Body Language: Writers on Sports . His essays have appeared several times in the Best American Essays series. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information ii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information iii THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BOXING EDITED BY GERALD EARLY Washington University, St. -

Fight Record Joe Beckett (Southampton)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Joe Beckett (Southampton) Active: 1912-1923 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 59 contests (won: 47 lost: 11 drew: 1) Fight Record 1912 Jan 29 Seaman McMullen DRAW(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 03/02/1912 page 338 Feb 3 Albert Croucher (Southampton) WPTS(6) Palace Theatre, Southampton Source: Boxing 10/02/1912 page 370 Promoter: Will Murray Feb 15 L/Cpl. Dyer (Gloucester Regt) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight competition 1st series) Referee: E Zerega Feb 15 Pte. Bancroft (RAMC) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight competition 2nd series) Referee: E Zerega Feb 19 Young Pughey (Brighton) LPTS4(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight novice competition 3rd series) Referee: JH Douglas extra round Mar 4 Seaman Nicholls (Southampton) WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 09/03/1912 page 470 Apr 22 Pte. Ponsford (RMLI) WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 27/04/1912 page 638 Apr 29 Fred Ball (Mile End) WRSF3(6) Dome, Brighton Source: Boxing 11/05/1912 page 44 Jun 10 Jim Hearne (Marylebone) WPTS(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/06/1912 page 157 Referee: G T Dunning Sep 30 Sid Broadbent WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 05/10/1912 page 546 Oct 14 Albert Lawner (Battersea) WKO4(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 19/10/1912 pages 593 and 594 Nov 18 Packey Mahoney (Ireland) LKO2 National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 23/11/1912 page 89 Mahoney boxed for the British Heavyweight Title 1913. -

Fight Record Johnny Basham (Newport)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Johnny Basham (Newport) Active: 1907-1929 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 101 contests (won: 76 lost: 17 drew: 8) Fight Record 1907 Jan 5 W Murphy (Newport) LRSF2 Newport Barracks, Monmouth Source: Sporting Life (7st competition semi-final) Referee: Harry Wheeler(Cardiff) 1908 Young Murphy LKO2 Newport Source: Johnny Basham biography by Alan Roderick Mar 6 Hunter (Newport) WRTD2(6) RFA Barracks, Newport Source: Sporting Life Apr 9 Lamprey WKO2(6) Barracks, Newport Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) 1909 Jun 10 T Scrivens WKO1(6) Tredegar Hall, Newport Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) Jul 9 E Thomas W(6) Tredegar Hall, Newport Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) Oct 18 Boxer Ryan WKO3 Campbell-Bannerman Hall, Newport Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) 1910 Jan 1 Fred Dyer (Cardiff) LRTD4(10) Drill Hall, Newport Source: Boxing 08/01/1910 page 459 Dyer boxed for the World Middleweight Title 1915. Referee: GT Dunning combined purse £20 £25 a side Jan 31 Badger Brien (Cardiff) LKO3 Badminton Club, Cardiff Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) Feb 12 Never Jones (Newport) WRSF10(15) Campbell-Bannerman Hall, Newport Source: Patrick White (Boxing Historian) (Monmouthshire Featherweight Title) Referee: Lew Morgan Promoter: Llew Morgan & Charlie Thomas combined purse £10 £5 a side Mar 2 Billy McKeiver (Chepstow) WKO3(8) Church Boys House, Chepstow Source: -

Boxer Died from Injuries in Fight 73 Years Ago," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 28, 2010

SURVIVOR DD/MMM /YEA RESULT RD SURVIVOR AG CITY STATE/CTY/PROV COUNTRY WEIGHT SOURCE/REMARKS CHAMPIONSHIP PRO/ TYPE WHERE CAUSALITY/LEGAL R E AMATEUR/ Richard Teeling 14-May 1725 KO Job Dixon Covent Garden (Pest London England ND London Journal, July 3, 1725; (London) Parker's Penny Post, July 14, 1725; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Teeling, Pro Brain injury Ring Blows: Manslaughter Fields) killing: murder, 30th June, 1725. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17250630-26. Covent Garden was a major entertainment district in London. Both men were hackney coachmen. Dixon and another man, John Francis, had fought six or seven minutes. Francis tired, and quit. Dixon challenged anyone else. Teeling accepted. They briefly scuffled, and then Dixon fell and did not get up. He was carried home, where he died next day.The surgeon and apothecary opined that cause of death was either skull fracture or neck fracture. Teeling was convicted of manslaughter, and sentenced to branding. (Branding was on the thumb, with an "M" for murder. The idea was that a person could receive the benefit only once. Branding took place in the courtroom, Richard Pritchard 25-Nov 1725 KO 3 William Fenwick Moorfields London England ND Londonin front of Journal, spectators. February The practice12, 1726; did (London) not end Britishuntil the Journal, early nineteenth February 12,century.) 1726; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), Richard Pro Brain injury Ring Misadventure Pritchard, killing: murder, 2nd March, 1726. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17260302-96. The men decided to settle a quarrel with a prizefight.