Our Sporting Heroes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fight Record Tom Mccormick (Dundalk)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Tom McCormick (Dundalk) Active: 1911-1915 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 53 contests (won: 42 lost: 9 drew: 2) Fight Record 1911 Private Walker WRSF1 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Bill Mansell (Hounslow) WRSF3 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Albert Bayton (Sheffield) WRSF2 Source: Larry Braysher (Boxing Historian) Apr 6 Pte. O'Keefe (Essex Regt) WRTD2(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 613, 614 and 616 (Inter-Allied Lightweight competition 1st series) Apr 8 Seaman Gray (HMS Formidable) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 613, 614 and 616 (Inter-Allied Lightweight competition 3rd series) Apr 10 Seaman White (HMS Patrol) WKO(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 611 and 612 (Inter-Services Lightweight competition semi-final) Apr 10 Sapper Jack O'Neill (Gloucester) LPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/04/1911 pages 611 and 612 (Inter-Services Lightweight competition final) Oct 18 Pte. Teale (Hussars) WPTS(3) Portsmouth Source: Boxing 28/10/1911 (Army and Navy Welterweight Championship 1st series) Oct 19 Cpl. Hutton (Stratford) LPTS(3) Portsmouth Source: Boxing 28/10/1911 (Army and Navy Welterweight Championship 2nd series) 1912 Jan 15 Bill Mansell (Hounslow) WRSF3(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 20/01/1912 page 291 Jan 20 Cpl. Hutton (Stratford) WRSF6(10) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 27/01/1912 pages 320, 321 and 322 Referee: B Meadows Jan 24 Charlie Milestone (Chester) WPTS(15) Manchester Regt. -

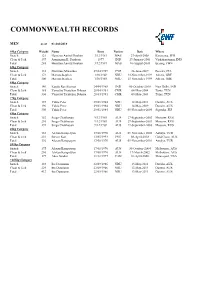

Commonwealth Records

COMMONWEALTH RECORDS MEN as at 01-Jul-2018 56kg Category Weight Name Born Nation Date Where Snatch 121 Hamizan Amirul Ibrahim 3/12/1981 MAS 27-April-2008 Kanazawa, JPN Clean & Jerk 147 Arumagam K. Pandyan 1977 IND 17-January-2001 Vishakapatnam, IND Total 265 Hamizan Amirul Ibrahim 3/12/1981 MAS 10-August-2008 Beijing, CHN 62kg Category Snatch 133 Dimitrios Minasides 29/04/1989 CYP 26-June-2009 Pescara, ITA Clean & Jerk 172 Marcus Stephen 1/10/1969 NRU 23-November-1999 Athens, GRE Total 300 Marcus Stephen 1/10/1969 NRU 23-November-1999 Athens, GRE 69kg Category Snatch 146 Katulu Ravi Kumar 24/04/1988 IND 06-October-2010 New Delhi, IND Clean & Jerk 185 Vencelas Tientchen Dabaya 28/04/1981 CMR 04-May-2004 Tunis, TUN Total 330 Vencelas Tientchen Dabaya 28/04/1981 CMR 04-May-2004 Tunis, TUN 77kg Category Snatch 157 Yukio Peter 29/01/1984 NRU 12-May-2011 Darwin, AUS Clean & Jerk 196 Yukio Peter 29/01/1984 NRU 14-May-2009 Darwin, AUS Total 350 Yukio Peter 29/01/1984 NRU 09-November-2005 Sigatoka, FIJ 85kg Category Snatch 182 Sergo Chakhoyan 9/12/1969 AUS 27-September-2003 Moscow, RUS Clean & Jerk 210 Sergo Chakhoyan 9/12/1969 AUS 27-September-2003 Moscow, RUS Total 392 Sergo Chakhoyan 9/12/1969 AUS 27-September-2003 Moscow, RUS 94kg Category Snatch 182 Alexan Karapetyan 17/08/1970 AUS 09-November-2001 Antalya, TUR Clean & Jerk 216 Steven Kari 13/05/1993 PNG 08-April-2018 Gold Coast, AUS Total 392 Alexan Karapetyan 17/08/1970 AUS 09-November-2001 Antalya, TUR 105kg Category Snatch 175 Alexan Karapetyan 17/08/1970 AUS 30-October-2004 Melbourne, -

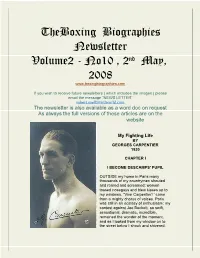

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume2 - No10 , 2Nd May, 2008

TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume2 - No10 , 2nd May, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My Fighting Life BY GEORGES CARPENTIER 1920 CHAPTER I I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL OUTSIDE my home in Paris many thousands of my countrymen shouted and roared and screamed; women tossed nosegays and blew kisses up to my windows. "Vive Carpentier! ' came from a mighty chorus of voices. Paris was still in an ecstasy of enthusiasm; my contest against Joe Beckett, so swift, sensational, dramatic, incredible, remained the wonder of the moment, and as I looked from my window on to the street below I shook and shivered. My father, a man of Northern France hard, stern, unemotional clutched the hand of my mother, whose eyes were streaming wet. Albert, also my two other brothers arid sister made a strange group. They were transfixed. Francois Descamps was pale; his ferret-like eyes blinked meaninglessly. Only my dog, Flip, now I come to think of it all understood for he gave himself over to howls of happiness. This day of unbounded joy so burnt itself into my mind that I shall remember it for all time. "Georges, mon ami," exclaimed my father, " no such moment did I ever think would come into our lives." And I understood. My life, as I look back upon it, has been a round of wonders. -

Print Layout 1

Lotteries 11/21/06 4:17 PM Page i LOTTERIES BEYOND FORTUNES Lotteries 11/21/06 4:17 PM Page ii ii Lotteries 11/21/06 4:17 PM Page iii LOTTERIES BEYOND FORTUNES N. SUGALCHAND JAIN, B.A SUGAL & DAMANI 6/35, W.E.A. Karol Bagh New Delhi - 110 005 iii Lotteries 11/21/06 4:17 PM Page iv © Sugal & Damani, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. This book contains information on a wide range of matters related to lottery, some of which depends upon interpretation of law. The information given in the book is not an exhaustive account of statutory requirements and should not be regarded as a complete or authoritative statement of law. The author accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of information that is variable in nature or opinion on the law expressed herein. The author accepts no liability for any loss or damage of any nature whether resulting from negligence or otherwise, however caused, arising from reliance by any person on the statements / information contained in this book. First published, 2005 Second Edition, 2006 Published by 'C' Wing, Kapil Tower, IV Floor Sugal & Damani 45, Dr. Ambedkar Road No.11, Ponnappa Lane Near Sangam Bridge Triplicane Pune - 411 001 Chennai - 600 094 Phone: 020 3987 1500 South India Phone : 044 - 2848 1354 / 2848 1366 1554, Sant Dass Street E-mail: [email protected] Clock Tower [email protected] Ludhiana - 141 008 Phone: 0161 2745 448 Price : Rs. -

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre Lewisham Library, 199-201 Lewisham High Street, London SE13 6LG The following items were received from Mrs Gillian Lindsay: Introduction W. (William) Howard Robinson was a noted representative artist and portrait painter of the early twentieth century. He was born on 3 November 1864 in Inverness-shire and attended Dulwich College from 1876 to 1882. He followed his father, William Robinson, into the Law and after a brief legal career studied Art at the Slade School under Sir Simeon Solomon. His professional career as a portrait painter began circa 1910 when his interest in the sport of fencing led him to sketch all the leading fencers of the day, these sketches were reproduced in the sporting publication “The Field” leading to further commissions for portraits with a sporting theme. He became well-known for his sketches and portraits of figures in the sporting world such as Lord Lonsdale, Chairman of the National Sporting Club. His two best known paintings were “An Evening at the National Sporting Club” (1918) and “A Welsh Victory at the National Sporting Club” (1922). This first painting was of the boxing match between Jim Driscoll and Joe Bowker, it took Robinson four years to complete and contained details of 329 sporting celebrities. The second painting commemorated the historic boxing match between Jimmy Wilde and Joe Lynch that took place on 31 March 1919 and shows the Prince of Wales entering the ring to congratulate the victor, the first time that a member of the royal family had done so. -

The Hand-Book to Boxing;

FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION NOTES: This document is an attempt at a faithful transcription of the original document. Special effort has been made to ensure that original spelling (this includes what may be typographical errors such as the 1776 reference on pp29 which should, apparently, be 1766 or pp39 where June 10 appears twice and should, at a guess, be July 10 in the second appearance, and, my favorite, July 40, on pp46), line-breaks, and vocabulary are left intact, and when possible, similar fonts have been used. However, it contains original formatting and image scans. All rights are reserved except those specifically granted herein. Of particular note in this reproduction is the unusual (by today’s standards) selection of page and font size. The page size is, in the original 6” x 10” with a font approximately 9 point for large portions of the book. Reproducing it in 6x9 with smaller top and bottom margins with hand tweaked font, paragraph, and line spacings, I have tried to recaptured the original personality of the book. However, this can make it difficult to read. Be assured that this was maintained in order to keep the “flavor” of the original text but it can be taxing on the eyes. LICENSE: You may distribute this document in whole, provided that you distribute the entire document including this disclaimer, attributions, transcriber forewords, etc., and also provided that you charge no money for the work excepting a nominal fee to cover the costs of the media on or in which it is distributed. You may not distribute this document in any for-pay or price- metered medium without permission. -

Yfj. HAS TWO GAMES VERY FAST and CHASES WILLARD SEVENTH CAVALET on CREDIT STRING CARRIES a PUNCH for TITLE MATCH to MEET TRAIN PASO Will a M P Team, by TORK, Dec

S-'- 1 LIFE 10 iL rA5U tltKALU UK I J, KHUKJbA IUIN ana UUIUOOK TRYING TO GET TUB GAME. CODY BASEBALL Kin M'PflRTIflP indoor sports OF THE GANG. BY "TAD FULTD SBEST FOOTBALL i ftoAiT" OF BIG BOXERS ARRANGED FOR TEAM TO VISIT LIKES WORK OF TCE of , AT MIGHT ii i TODAY, GHHISTIIUIS DHf GITYSATURDAYBENNY LEONARD wmm ' smoke 'l .iWM Her sota nK "Will Clash Cantonment Nine Will En - Veteran Referee Declares! Would Undoubtedly Defeat Cavalry Teams AtK Pad - '". gage Fort Bliss in Final j That Lightweight King fi! ?yT"C"GUT- All Contenders for the at Stadium in Afternoon Two Games of Series. Is the Best Ever. I Heavyweight Title. of Holiday. i Yfj. HAS TWO GAMES VERY FAST AND CHASES WILLARD SEVENTH CAVALET ON CREDIT STRING CARRIES A PUNCH FOR TITLE MATCH TO MEET TRAIN PASO will A M P team, By TORK, Dec. .Fred Ful football enthusiasts OODTS crack baseball JACK VBIOCK. on I recently trimmed the Ft. YORK, Dec. 20. Mc 1ST ton has shown himself to be not be left oat In the cold Kid heavyweight In E" spite th" Bliss nine In two decisive battles Partland, recognized in the the best the Christmas dar in of country, barring champion, and Bliss-Cod- y return on the cantonment diamond, will in-- v N"east as one of the best of pres tbe calling off of the if V.' 11 any of again game, arrange 1 .ae HI Paso Saturday and Sunday ent day referees, has advanced a new lard has intention as a contest has been Ie fon tl i n g his title the Minneaotan cavalry regi- s f t en oon, and a combined front of argument to substantiate the con between the Serenth , the logical opponent. -

Fight Record Tom Thomas (Wales)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Tom Thomas (Wales) Active: 1905-1911 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 22 contests (won: 20 lost: 2) Fight Record 1905 Jan 28 Harry Shearing (Walthamstow) WKO3(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Jul 22 Seaman Dunstan (Portsmouth) WRTD3(15) Queens Street Hall, Cardiff Source: Mirror of Life (Welsh Middleweight Title) Referee: JT Hulls combined purse £50 £25 a side Dunstan described as Navy Middle Champion - 4oz gloves 1906 Feb 24 Billy Edwards (Australia) WKO3(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Referee: JT Hulls junior Promoter: Harry Jacobs Mar 31 Bill Cockayne (Kentish Town) WRTD2(6) Wonderland, Whitechapel Source: Sporting Life Referee: Brummy Meadows Promoter: Harry Jacobs Apr 9 Pte. Casling (Grenadier Gds.) WKO1(10) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life Referee: JH Douglas Apr 26 P.O. Jim McDonald (RN) WRTD2(6) Tower, London Source: Sporting Life McDonald Navy Champion in 1905 and 1906 May 28 Pat O'Keefe (Canning Town) WPTS(20) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life O'Keefe was British Middleweight Champion 1906 and 1914-16 and 1918-19. Referee: JH Douglas 1908 Apr 30 Mike Crawley (Limehouse) WKO5(10) West End School of Arms, Marylebone Source: Sporting Life Referee: HG Mankin Jun 1 Tiger Smith (Merthyr) WKO4(20) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Sporting Life (British Middleweight Title) -

Myrrh NPR I129 This Newsletter Is Dedicated to the Nucry of Jim

International Boxing Research Organization Myrrh NPR i129 This newsletter is dedicated to the nucry of Jim Jacobs, who was not only a personal friend, but a friend to all boxing his- torians. Goodbye, Jim, I'll miss you. From: Tim Leone As the walrus said, "The time has come to talk of many things". This publication marks the 6th IBRO newsletter which has been printed since John Grasso's departure. I would like to go on record by saying that I have enjoyed every minute. The correspondence and phone conversations I have with various members have been satisfing beyond words. However, as many of you know, the entire financial responsibility has been paid in total by yours truly. The funds which are on deposit from previous membership cues have never been forwarded. Only four have sent any money to cover membership dues. To date, I have spent over $6,000.00 on postage, printing, & envelopes. There have also been a quantity of issues sent to prospective new members, various professional groups, and some newspapers.I have not requested, nor am I asking or expecting any re-embursement. The pleasure has been mine. However; the members have now received all the issues that their dues (sent almost two years ago) paid for. I feel the time is prudent to request new membership dues to off-set future expenses. After speaking with various members, and taking into consideration the post office increase April 1, 1988, a sum of $20.00, although low to the point of barely breaking even, should be asked for. -

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: Click Nationality: British

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: click Nationality: British Birthplace: Edinburgh, Scotland Hometown: Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom Born: 1945-06-28 Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7½″ Reach: 178 Manager: Eddie Thomas Trainer: Gil Clancy 1965 ABA featherweight champion International Boxing Hall of Fame Bio Further Reading: The Tartan Legend: The Autobiography http://www.stv.tv/info/sportExclusive/20070618/Ken_Buchanan_interview_180607 Ken Buchanan was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 28 June 1945, to p a r e n t s Tommy and Cathie. both of whom were very supportive of their son's sporting ambitions throughout his early life. However, it wa s Ken's aunt, Joan and Agnes, who initially encouraged the youngster's enthusiasm for boxing. In 1952. the pair were shopping for Christmas presents for Ken and his cousin. Robert Barr. when they saw a pair of boxing gloves and it occurred to them that the two boys often enjoyed some playful sparring together. So. at the age of seven, the young Buchanan received his first pair of boxing gloves. It was another casual act, this time by father Tommy that sparked young Ken's interest in competitive boxing. One Saturday, when the family had finished shopping, Tommy took his son to the cinema to see The Joe Louis Story and Ken decided he'd like to join a boxing club. Tommy agreed. and the eight-year-old joined one of Scotland's best clubs. the Sparta. Two nights a week, alongside 50 other youths, young Ken learned how to box and before long he had won his first medal – with a three-round points win in the boys' 49lb (three stone seven pound) division. -

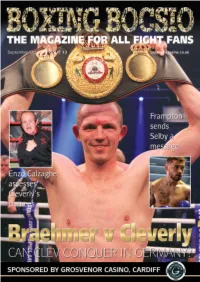

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

HLETIC GAME! CARPENTIER's [This Sicene Will Be Enacted Just Before Bell for Firist Round J!BRONX BOYS RETAIN IN

f Q 4 THE: NEW YORK HERALE), SUNDAY, JUNE 12, 1921. O ' AT THIv CAM1>S OK rHE BICr BOXERS - ATHLETIC GAME! CARPENTIER'S [This Sicene Will Be Enacted Just Before Bell for Firist Round j!BRONX BOYS RETAIN IN. Y.A.C.Ath/efes in VIGORj P.S.A.L. TEAM TITLE\ Junior Championshiv TOBGTESTEDJULY2 <kr I Continued First i r .... I I..^im/iAccfnl Ii» HftfnnH ll iuwti'v ff from Page. New Junior Metropolitan Ability of Challenger to Games at the field carrying: before It a cloud of j Sur-j Championship of A. A. U. » rive Jolts Will Be dust that lasted all during the contests, Champions Heavy Brooklyn Field. This wind slowed up most of the races. 100 > «Rn IIASll-UrKini Prin<-rtnn 11.,I I Definitely Settled. vrrsily. surely handicapped their efforts. 220 1 V CI> Ht'N.Yonhass, r.lrnior A. / >$ Pupils of Public School No. 37 of Th< Y'AICD Itl N.Stesrnson, Prince Princeton took things right In hand I'nlt entity. Bronx successfully defended ihelr tearr by getting both first and second in the 880 Y'AICD itl N.Parker, St. < liristop DEMPSEY SUKE TO LAND the annual field ant 100 A. « titular honors In yards dash with McKIm and T-leber- Mil.I. Itl N .flrennu, New York A. C. track champlonelps of the P. S. A. L. ai man, who outclassed their competitors. THK/.r. Mil i: Itl V.Kick. Princeton. The I .'U Y Athletic Field Th< tlrne of 10 2-5 seconds into the wind Altl> III ItlH.KS.Zunter, N.