Fig.1 Fig.2 Fig.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Defence and Emergency Management Group Committee Meeting Held on 30/08/2017

Auckland Tsunami Community Exposure Analysis R.J. Woods A. E. Lewis GNS Science Consultancy Report 2017/74 May 2017 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to Auckland Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of or reliance on any contents of this report by any person other than Auckland Council and shall not be liable to any person other than Auckland Council, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. Use of Data: Date that GNS Science can use associated data: April 2017 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Woods, R.J.; Lewis, A. E., 2017. Auckland Tsunami Community Exposure Analysis, GNS Science consultancy report 2017/74. 48 p. Project Number 470W1369 Confidential 2017 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. IV 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 2.0 SCENARIOS .....................................................................................................2 2.1.1 Day and Night Scenarios ......................................................................... 2 2.1.2 Fine, Summer Day Scenario ................................................................... 2 2.1.3 Tsunami Inundation Scenario .................................................................. 2 3.0 METHODOLOGY -

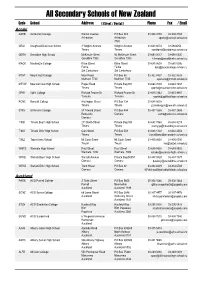

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Community Urban Restoration & Ed Guide

Community Urban Restoration & Education LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE Guide VOLCANO TO SEA PROJECT Community Urban Restoration and Education Guide: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lessons learnt from the Volcano to Sea Project This guide has been produced by NZ Landcare Trust, Published by NZ Landcare Trust, May 2015 as part of the Volcano to Sea Project, funded by the Ministry for the Environment and also generously ISBN 978-0-9941066-5-0 (print) supported by Auckland Council. ISBN 978-0-9941066-6-7 (pdf) We would like to acknowledge project partners such NZ Landcare Trust as the Howick Local Board, Hauraki Gulf Forum, PO Box 4305 Sustainable Coastlines, Iwi (Ngai Tai ki Tamaki Tribal Hamilton 3247 Trust), the Enviroschools Foundation, local schools www.landcare.org.nz and the numerous business and community groups 0800 526 322 that helped out with so many different education, awareness-raising, litter clean-up and planting events. Written by: Heidi Clark and Karen Denyer Edited by: James Barnett, NZ Landcare Trust It is important to highlight that the Auckland Council provided professional, hands-on and financial Graphic Design: Abby Davidson, NZ Landcare Trust support to the project through various initiatives and Photography: NZ Landcare Trust unless otherwise departments. The following areas all deserve to be credited within document recognised for their involvement: Local and Sports Parks South, Sustainable Catchments, Wai Care, Enviroschools and the Stormwater team. A catchment project of this size truly requires everyone working together and NZ Landcare Trust would like This project was funded by the Ministry for the to sincerely thank every organisation, contractor and Environment’s Community Environment Fund. -

New Network for East Auckland Consultation and Decisions Report

New Network for East Auckland Consultation and Decisions Report Contents 1. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Background and Strategic Context ................................................................................................. 3 4. The Decision-Making Process ......................................................................................................... 4 5. Consultation Overview ..................................................................................................................... 5 5.1 Pre-Consultation ......................................................................................................................... 5 5.2 Consultation Period .................................................................................................................... 5 5.3 Post-Consultation Activity ......................................................................................................... 6 6. Public Engagement .......................................................................................................................... 6 6.1 Stakeholder Engagement ........................................................................................................... 6 6.2 Consultation Brochure .............................................................................................................. -

Intertidal Life of the Tamaki Estuary and Its Entrance, Auckland July 2005 TP373

Intertidal Life of the Tamaki Estuary and its Entrance, Auckland July 2005 TP373 Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication No. 373, 2008 ISSN 1175-205X(Print) ISSN 1178-6493 (Online) ISBN 978-1-877483-47-9 Intertidal life of the Tamaki Estuary and its Entrance, Auckland Bruce W. Hayward1 Margaret S. Morley1,2 1Geomarine Research, 49 Swainston Rd, St Johns, Auckland 2c/o Auckland War Memorial Museum, Private Bag 92 018, Auckland Prepared for Auckland Regional Council Envrionmental Research 2005 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Auckland Regional Council Approved for ARC publication by: _____________________________ Grant Barnes 21 July 2008 Recommended Citation: Hayward, B. W; Morley, M.S (2005). Intertidal life of the Tamaki Estuary and its entrance, Auckland. Prepared for Auckland Regional Council. Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication Number 373. 72p Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction 3 2.1 Study Area 3 2.2 Rock Types Along the Shore 6 2.3 Origin and Shape of the Tamaki Estuary 6 2.4 Previous Work 7 2.4.1 Ecological Surveys 7 2.4.2 Introduced Species 7 2.4.3 Environmental Pollution 8 2.4.4 Geology 9 2.5 Tamaki Estuary Steering Committee 9 3 Methodology 10 3.1 Survey Methodology 10 3.2 Biodiversity and Specimens 10 4 Intertidal Habitats and Communities 11 4.1 Salt Marsh and Salt Meadow 11 4.2 Mangrove Forest 11 4.3 Seagrass Meadows 12 4.4 Sublittoral Seaweed Fringe 12 4.5 Estuarine Mud 12 4.6 Shelly Sand Flats 12 4.7 Shell Banks and Spits -

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1 Chapter 6 — Heritage CONTENTS This chapter is presented as follows: 6.1 Introduction This outlines how heritage is defined and the statutory context of this chapter. 6.2 Resource Management Issues This outlines the significant resource management issues relating to heritage resources within the City. 6.3 Objectives This sets out the overall desired environmental outcomes for the heritage resources of the City. 6.4 Policies This describes how Council intends to ensure that the objectives for the City’s heritage resources are met. An explanation of the policies is given. A summary of the range of methods that are used to implement each policy is also included. 6.5 Heritage Strategy The strategy summarises the overall approach to managing the City’s natural and cultural heritage resources. 6.6 Implementation This broadly describes the regulatory and non-regulatory methods used to implement the policies for the management of the City’s heritage resources. 6.7 Anticipated Environmental Results This outlines the environmental outcomes anticipated from the implementation of the policies and methods as set out in the Heritage Chapter. 6.8 Procedures for Monitoring This outlines how Council will monitor the effectiveness of the Heritage provisions. Manukau Operative District Plan 2002 Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 2 6.9 Rules — Activities This sets out in an Activity Table the permitted and discretionary activities for the scheduled heritage resources of the City. 6.10 Rules – Matters for Control: Controlled Activities 6.11 -

Commercial Member Directory

Commercial Member Directory Barfoot & Thompson Commercial 34 Shortland Street +64 9 3076300 [email protected] Auckland, 1140 www.barfoot.co.nz Title Name Email Phone # Commercial Referral Coordinator John Urlich [email protected] +64 21395396 Commercial Broker in Charge Peter Thompson [email protected] +64 9 3075523 Certifications Applies Service Tiers Applies ALC Commercial Division/Office BOMA Dedicated Commercial Agent(s) Build-to-suit Resi-Mercial Agent(s) CCIM CPM Lease negotiation SIOR Service Types Applies Network Affiliations Applies Hotel / Resort CBRE CORFAC Industrial CRESA Investment CW/DTZ Land / Agricultural JLL Knight Frank Landlord Rep NAI Leasing Newmark TCN Service Types Applies Logistics Medical Office Multi-Family Office Property Management Retail Tenant Rep City State / Province Country Ahuroa NZL Albany NZL Albany Heights NZL Alfriston NZL Algies Bay NZL Ararimu NZL Ardmore NZL Arkles Bay NZL Army Bay NZL Auckland NZL Avondale NZL Awhitu NZL Bay Of Islands NZL Bay View NZL Bay of Plenty NZL Bayswater NZL Bayview NZL Beach Haven NZL Beachlands NZL Belmont NZL Big Bay NZL Birkdale NZL Birkenhead NZL Birkenhead Point NZL Bland Bay NZL Blockhouse Bay NZL Bombay NZL Botany Downs NZL City State / Province Country Broadwood NZL Brookby NZL Browns Bay NZL Buckland NZL Bucklands Beach NZL Burswood NZL Cable Bay NZL Campbells Bay NZL Canterbury NZL Castor Bay NZL Central Otago NZL Chatswood NZL City Centre NZL Clarks Beach NZL Clendon Park NZL Clevedon NZL Clover Park NZL Coatesville NZL Cockle -

Where to Catch Your Bus in the City

Where to catch your bus in the city Ferries depart here for: Birkenhead, Northcote Pt, Britomart Transport Centre Bayswater, Devonport, Bledisloe Jellicoe Half Moon Bay (weekends) Downtown Ferry Terminal Wharf Wharf Ferries depart here for: Quay St Quay St Waiheke Island, Half Moon Bay (weekdays) 703HSBC 710 713 715 Freyberg 716 717 745 750 Gore St Ferries depart here for: Captain West Harbour, 755 756 757Marsden767 Tyler St Wharf Pine Harbour Cook 7010 Queen Wharf769 7024 WharfElizabeth Station Te Ara Tahuhu Walkway Ferries depart here for: Queens Square Plaza Takutai Gulf Harbour, Downtown Commerce St Britomart Station 7026 Square Stanley Bay Wharf Shopping Centre Queen St Lower Albert St Galway St 500 501 502 511 Tooley St 7012 7046 t 512 522 532 550 S MERCURE PIER HOTEL t ey l 625 635 551 552 595 S PIER 1 n r 7018 i e PIER PIER 2 Customs St W 645 655 Customs StT E 703 710 713 m 4 3 u 715 716 717 Pl Ferry Building 745 750 755 1018 Quay St 756 757 767 Quay 769 7302 Price HSBC St Waterhouse t EAST Coopers Tyler St S Queen Britomart Elizabeth a r Transport t Square o S p Centre a 635 T Downtown ua AMP Shopping Galway St h r 645 gi C Centre Centre hu Vector n u a h a 655 T Arena M Customs St West Customs St East West DFS Galleria E mi 7140 Plaza C ly o F The Railway mm t 500 501 7182 Pl o Quay S r West t Oaks Campus Ln er Residence 502 511 Mills Lane ore c G Wolfe St e Lumley B Centre 512 522 e Te Taou Cr St ach R Fort St 532 550 d Exchange Ln Deloitte St A rt nz ne Centre o ac Ave Vero 551 552 h Cr La ANZ Stamford S u ls Centre Plaza -

We Are the Readers Choice

Times Media MEDIA KIT We are the readers choice CN 0 CN 0 CN 0 A Awards 202 A Awards 202 A Awards 202 Publishers of SOUTH EAST | FRANKLIN East design Auckland Settling In build App FREE! ruralliving.co.nz July/August 2020 Voted best magazine www.ruralliving.co.nz CN 0 A Awards 202 Rural Living is directed at small block owners – suits and gumboots people who may work in the city but live in the country as well as catering to the new urban estates, IONE CUSSEN: Rural Living is renowned for its diverse ON TIME’S SIDE content. Readers can expect light hearted humour, topical farming and horticultural Spotlight on STOCK HIS news and coverage of town and country PATUMAHOE TRADE – YOUNG themes with local personalities in the mix. GLENBROOK: WHERE THE FARMER MIGHTYMICROS EYES GROW... FUTURE www.ruralliving.co.nz Rural Living — July/August 2020 — 1 DISTRIBUTION RLJuly-Aug 2020.indd 1 15/07/2020 3:29:21 PM Delivered to RD 1,2,3 and 4 rural lifestyle properties in the greater Franklin district and beyond – Pokeno to Drury/Karaka and Clevedon to Waiuku as well as to drop boxes throughout the districts regional townships CN 0 including their key community of Pukekohe. A Awards 202 Printed ADVERTISING RATES distribution SIZE CASUAL 6 ISSUE 12 ISSUE RATE RATE RATE 15,000 Double Page Spread $2500 $1625 $1500 Full Page $1490 $968 $894 1/2 Page $990 $742 $594 Digital 1/3 Page $795 $625 $450 subscribers 1/4 Page $595 $446 $392 1/8 Page $395 $295 $221 3,500 Dining Guide $390 $195 Directory – Double $295 $221 $195 Directory – Single $195 $146 $97 DEADLINES: Booking deadlines Design / Artwork FREE are on the 5th of each month; for Photographer per hour on request content requiring creative input, the 10th of each month; print- Hyperlink FREE ready content can be supplied Rates are per issue, GST exclusive and non-commission bearing. -

Alfriston College Aorere College Botany Downs Secondary College

Alfriston College Aorere College Botany Downs Secondary College Bucklands Beach Intermediate School Destiny School Drury School Elim Christian College Howick College Howick Intermediate School Macleans College Manurewa High School Manurewa Intermediate School Maraetai Beach School Otahuhu Intermediate School Pukekohe High School Randwick Park School Saint Kentigern College Somerville Intermediate School Tyndale Park Christian School 1 CONVENOR’S REPORT It gives me great pleasure to be associated with the 2009 MIT Manukau Science and Technology Fair. This is our fifteenth year as a full Regional Fair and we continue the tradition of previous years enthusiastically. For many students the fair provides a platform outside of the confines of the classroom to explore an area of interest. Past award winning participants all agree that their participation and achievements in the fair have helped them to secure a variety of scholarships and prizes, as well as boosting their applications for places in restricted courses at tertiary institutions. The successful award winners tonight represent the best of hundreds of projects in our region from nineteen participating schools. The committee and judges have been very impressed with both the high standard of presentation of work and the ingenious and innovative nature of the investigations undertaken by students. Each exhibit represents hours of toil which often extends over a number of weeks. These projects are in most cases the result of considerable input and guidance from parents and teachers.To produce work of this calibre requires a high quality of teaching and learning – I believe that the work shown here tonight reflects very favourably on the sort of good learning that is taking place in Manukau City classrooms. -

Probabilistic Hazard Analysis and Modelling of Tsunami Inundation for the Auckland Region from Regional Source Tsunami

Probabilistic Hazard Analysis and Modelling of Tsunami Inundation for the Auckland Region from Regional Source Tsunami Philip Gillibrand William Power Emily Lane Xiaoming Wang Julian Sykes Hannah Brackley Jade Arnold Prepared for Auckland Regional Council © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the client. Such permission is to be given only in accordance with the terms of the client's contract with NIWA and GNS. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. By National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd 10 Kyle Street, Riccarton, Christchurch 8011, P O Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand Phone +64‐3‐348 8987, Fax +64‐3‐348 5548, www.niwa.co.nz and Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences Ltd PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Phone +64‐4‐570 14444, Fax +64‐4‐570 4600, www.gns.cri.nz NIWA Client Report: CHC2010‐102 GNS Consultancy Report 2010/200 NIWA Project: ARC10502 GNS Project No.: 410W1164 August 2010 Reviewed by: Released by: Name: Scott Stephens Name: Graham Fenwick Position Scientist Coastal Hydrodynamics Position Assistant Regional Manager Organisation: NIWA Organisation: NIWA Date: October 2010 Date: October 2010 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction 3 3 Methods 5 3.1 Regional source tsunami hazard estimation at the 2500 year ARI 84‐percentile level and selection of stochastic scenario ensemble for inundation modelling 5 3.2 Unit Source Modelling: The COMCOT model 12 3.3 Inundation Modelling 13 3.3.1 The Inundation Model: RiCOM 14 3.3.2 The Inundation Grid 14 3.3.3 COMCOT – RiCOM Comparison 15 3.4 Probabilistic Analysis of Inundation 19 3.4.1 Monte Carlo simulation of Annual Exceedance Probabilities excluding tides.