Militants and the Media: Partners in Terrorism? William R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Our Fans, Our Friends, and Our Families

CredCred its its Written & Designed by: Shane Lacy Hensley Additional Material by: John Hopler & Matt Forbeck Editing: Matt Forbeck Layout: Matt Forbeck & Shane Lacy Hensley Front Cover Art: Paolo Parente Back Cover Art: Brian Snoddy Logos: Ron “Voice o’ Death” Spencer & Charles Ryan Graphic Design: Hal Mangold & Charles Ryan Interior Art: Thomas Biondolillo, Mike Chen, Jim Crabtree, Kim DeMulder, Paul Daly, Marcus Falk, Mark Dos Santos, Tom Fowler, James Francis, Darren Friedendahl, Tanner Goldbeck, Norman Lao, Ashe Marler, MUTT Studios, Posse Parente, Matt Roach, Jacob Rosen, Mike Sellers, Kevin Sharpe, Jan Michael Sutton, Matt Tice, George Vasilakos & Loston Wallace Advice & Suggestions: Paul Beakley, Barry Doyle, Keith & Ana Eichenlaub, John & Joyce Goff, Michelle Hensley, Christy Hopler, Jay Kyle, Steven Long, Ashe Marler, Jason Nichols, Charles Ryan, Dave Seay, Matt Tice, Maureen Yates, Dave “Coach” Wilson & John Zinser Special Thanks to: All the folks who supported Deadlands: our fans, our friends, and our families. Pinnacle Entertainment Group, Inc. Deadlands, Weird West, Wasted West, Hell on www.peginc.com Earth, the Deadlands logo, the Pinnacle Starburst, and the Pinnacle logo are Trademarks Dedicated to: of Pinnacle Entertainment Group, Inc. Caden. © 1Pinnacle Entertainment Group, Inc. All Rights Who’s raised a little Hell on Earth of his own. Reserved. ™ Table o’ Contents Chapter Chapter Three: Chapter Five: One: The The Stuff Blowin’ Things Prospector’s Heroes Are All to Hell............... 8 1 Story.................................5 Made Of ................... 2 5 Movement ......................................... 84 A History Lesson ........................7 One: Concept ................................ 25 Tests o’ Will ................................... 86 The Last War .................................. 9 Two: Traits ...................................... 28 Shootin’ Things ......................... 87 The Wasted West .................... -

112508NU-Ep512-Goldenrod Script

“Jacked” #512/Ep. 91 Written by Don McGill Directed by Stephen Gyllenhaal Production Draft – 10/30/08 Rev. FULL Blue – 11/6/08 Rev. FULL Pink – 11/11/08 Rev. Yellow – 11/13/08 Rev. Green – 11/17/08 Rev. Goldenrod – 11/25/08 (Pages: 48.) SCOTT FREE in association with CBS PARAMOUNT NETWORK TELEVISION, a division of CBS Studios. © Copyright 2008 CBS Paramount Network Television. All Rights Reserved. This script is the property of CBS Paramount Network Television and may not be copied or distributed without the express written permission of CBS Paramount Network Television. This copy of the script remains the property of CBS Paramount Network Television. It may not be sold or transferred and must be returned to: CBS Paramount Network Television Legal Affairs 4024 Radford Avenue Administration Bldg., Suite 390, Studio City, CA 91604 THE WRITING CREDITS MAY OR MAY NOT BE FINAL AND SHOULD NOT BE USED FOR PUBLICITY OR ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT FIRST CHECKING WITH TELEVISION LEGAL DEPARTMENT. “Jacked” Ep. #512 – Production Draft: Rev. Goldenrod – 11/25/08 SCRIPT REVISION HISTORY COLOR DATE PAGES WHITE 10/30/08 (1-58) REV. FULL BLUE 11/6/08 (1-58) REV. FULL PINK 11/11/08 (1-59) REV. YELLOW 11/13/08 (1,3,4,6,10,11,17,18,19, 21,25,27,29,30,30A,40,42, 47,49,49A,50,51,53,55, 55A,56,56A,57,59,60.) REV. GREEN 11/17/08 (3,6,19,21,35.) REV. GOLDENROD 11/25/08 (48.) “Jacked” Ep. #512 – Production Draft: Rev. FULL Pink – 11/11/08 CAST LIST DON EPPES CHARLIE EPPES ALAN EPPES DAVID SINCLAIR LARRY FLEINHARDT AMITA RAMANUJAN COLBY GRANGER LIZ WARNER TIM KING BUCKLEY LEN WALSH JACK SHULER/HAWAIIAN SHIRT GUY CAITLIN TODD BUS DRIVER MOTHER BUS TECH N.D. -

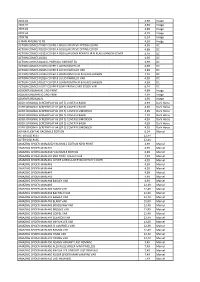

Bookexpress Catalogue by Publisher

BookExpress Catalogue Sorted by publisher ( Financial Awareness Corp. ) File generated 09/19/21 Title Author ISBN Pub Subj Price Bd Date Wealthy Barber Returns Chilton, David 9780968394748 5313 Busi $ 19.95 PB Smart Risk Wong, Maili 9781599326023 5319 Busi $ 36.00 CL Frontlist titles in Bold Page: 1 of 97 BookExpress Catalogue Sorted by publisher ( Aona Books ) File generated 09/19/21 Title Author ISBN Pub Subj Price Bd Date Rest, Play, Grow MacNamara, Deborah 9780995051201 5321 Chca $ 19.99 PB Frontlist titles in Bold Page: 2 of 97 BookExpress Catalogue Sorted by publisher ( Andrews & McMeel Canada ) File generated 09/19/21 Title Author ISBN Pub Subj Price Bd Date 2022 Cartoons from the New Yorker Day Conde Nast 9781524863326 A&M Cal $ 20.99 DK Frontlist titles in Bold Page: 3 of 97 BookExpress Catalogue Sorted by publisher ( Thomas Allen & Son Limited ) File generated 09/19/21 Title Author ISBN Pub Subj Price Bd Date ABC's of Black History, The Cortez, Rio ; Semmer, 9781523507498 ALL Chpi $ 19.95 CL Afterlife Alvarez, Julia 9781643751368 ALL Fict $ 22.95 PB Barnyard Bath! Boynton, Sandra 9780761147183 ALL Chyr $ 13.95 BJ Barnyard Dance Boynton, Sandra 9781563054426 ALL Chbd $ 10.95 BH Bath Time! Boynton, Sandra 9780761147084 ALL Chil $ 13.95 BJ Beautiful Oops! Saltzberg, Barney 9780761157281 ALL Chaa $ 22.95 CL Belly Button Book Boynton, Sandra 9780761137993 ALL Chbd $ 10.95 BH Book of Awakening, The Nepo. Mark 9781590035009 ALL Insp $ 26.95 PB Dinosnores Boynton, Sandra 9781523508136 ALL Chbd $ 10.95 BH Eight Dates Gottman & Gottman 9781523504466 ALL Relat $ 34.95 CL Electrical Code Simplified Knight, P.S. -

Focus on Destruction KAPUTT: the Academy of Destruction at Tate Modern, October 2017 a Response by Mary Paterson

Focus on Destruction KAPUTT: The Academy of Destruction at Tate Modern, October 2017 A response by Mary Paterson For six days in the summer of 2011, thousands of young people rioted across England. In London, Manchester and the West Midlands they broke into shops, looted property and set buildings ablaze. The riots began on 6th August and effervesced until the 11.th By 13th August, over 3,000 people had been arrested. In time, more than 2,000 people were sent to jail for damaging property, rioting and encouraging others. A mother of two got five months behind bars for receiving a pair of stolen shorts, although she had been asleep while the looting took place. Local police tweeted in celebration of her sentence. I watched the riots radiate round the country like nerve pain and wondered what was going to change. The answer came quickly: nothing. This surge in activity, this violent outburst, this unpredicted eruption of unspoken feeling would change not a single thing in the fabric of our public space. Instead, it would be suppressed with force, punishment and silence from the political class about the reasons the riots took place. It would be met, in other words, by a surge of activity: a violent outburst, an unpredicted eruption of power, grinding the lives of the rioters under the heel of the state. This is the story of destruction in our society: destructive energy is always negative (rioting) unless it is wielded by people in power (government crackdown); when it’s wielded by people in power, of course, it’s called something like ‘order’, or ‘the national interest’, or ‘austerity’. -

Title Author Description Copies Available

Title Author Description Copies Available Everybody sing along—because it's time to do-si-do in the barnyard with a high-spirited animal crew! From Boynton on Board, the bestselling series of board books, here is BARNYARD DANCE, with Sandra Boynton's twirling pigs, fiddle- Barnyard Dance! Sandra Boynton playing cows, and other unforgettable animals. Extra-big, extra-fat, and extra-fun, BARNYARD DANCE features lively 2 rhyming text and a die-cut cover that reveals the wacky characters inside. Guaranteed to get kids and adults stomping their feet. Giraffes Can't Dance is a touching tale of Gerald the giraffe, who wants nothing more than to dance. With crooked knees and thin legs, it's harder for a giraffe than you would think. Gerald is finally able to dance to his own tune when he gets some Giraffes Can't Dance Giles Andreae 2 encouraging words from an unlikely friend. With light-footed rhymes and high-stepping illustrations, this tale is gentle inspiration for every child with dreams of greatness. Beep! Beep! Beep! Meet Blue. A muddy country road is no match for this little pick up--that is, until he gets stuck while pushing a dump truck out of the muck. Luckily, Blue has made a pack of farm animal friends along his route. And they're Little Blue Truck Alice Schertle willing to do whatever it takes to get their pal back on the road. With a text full of truck sounds and animal noises to read 1 Board Books aloud, here is a rollicking homage to the power of friendship and the rewards of helping others. -

Unite Or Divide?

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Elizabeth A. Cole and Judy Barsalou In November 2005, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), with assistance from the Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs (CCEIA), hosted a three-day conference, “Unite or Divide? The Challenges of Teaching History in Societies Emerging from Violent Conflict.” Participants included 28 teachers, education ministry officials, academic historians, transitional justice experts, Unite or Divide? and social scientists from around the world; approximately one-third are current or former Institute grantees. The conference explored how divided societies recovering from The Challenges of Teaching History in violent conflict can teach the conflict’s history, so as not to re-ignite it or contribute to future cycles of violence and Societies Emerging from Violent Conflict to participate in a larger process of social reconstruction and reconciliation. Organizers included Judy Barsalou (vice president of USIP’s Grant and Fellowship Program) and Elizabeth A. Cole (assistant director of TeachAsia at the Asia Summary Society and former director of the History and the Politics of Reconciliation Program at CCEIA). • In deeply divided societies, contending groups’ historical narratives—especially the official versions presented most often in state-run schools—are intimately connected to the groups’ identities and sense of victimization. Such narratives are often contra- The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace, dictory and controversial. History taught in schools is highly susceptible to simplified which does not advocate specific policy positions. -

Project Nur, El FIC 150 "I Love My Air Fryer" Keto Diet Recipe Book

TITLE AUTHOR Categ Pesos 'life' Project Nur, El FIC 150 "i Love My Air Fryer" Keto Diet Recipe Book: From Veggie Frittata to ClassicDillard, MinSamCKB 410 (Nearly) Teenage Girl's Guide to (Almost) Everything Coombes, SharieYAN 200 #lovemutts: A Mutts Treasury McDonnell, CGNPatrick 480 1-2-3, You Love Me Jill HowarthKIDS 200 1, 2, 3 To The Zoo: A Counting Book Carle, Eric/ KIDSCarle, Eric 200 1,000 Facts about Ancient Egypt Honovich, NancyJNF 360 10 Fat Turkeys Deas, Rich JUV 170 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric JUV 220 10 Practice Tests for the Sat, 2020 Edition: Extra Preparation to Help AchieveThe Princeton a STU Review 600 10% Happier Revised Edition: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, ReducedHarris, DanStressSEL Wi 410 100 Christmas Wishes: Vintage Holiday Cards from the New York PublicNew Library York PublicREL Library 440 100 Drives, 5,000 Ideas: Where to Go, When to Go, What to Do, WhatYogerst, to See JoeTRV 600 100 Inventions That Made History DK PublishingJNF 410 100 stories day 21 morgan cassJUV 290 100 Weight Loss Bowls: Build Your Own Calorie-Controlled Diet Plan Whinney, HeatherCKB 480 1000 Animals revised ANI 360 1000 Dot-To-Dot: Masterpieces Pavitte, ThomasKIDS 360 1000 Things Under the Sea Revised NAT 360 1001 Animals To Spot Brocklehurst,JUV Ruth/ Gower, 240 Ter 1001 Quotations to Enlighten, Entertain, and Inspire Arp, Robert REF 440 101 Dalmatians Coloring Book: Coloring Book for Kids and Adults 50 IllustrationsOrneo, JulianaCRA 170 102 Dalmatians and Madagascar Escape 2 Africa Coloring Book: 2 in Westfild,1 Coloring Angela BooCRA 150 104-Story Treehouse: Dental Dramas & Jokes Galore! Griffiths, AndyJUV 340 11/22/63 King, StephenFIC 480 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos Peterson, JordanPSY B 630 13 Things Mentally Strong Parents Don't Do Intl Amy Morin FAM 440 13 Things Mentally Strong Women Don't Do: Own Your Power, ChannelMorin, Your Amy ConfidencSEL 440 13-Story Treehouse book 1 Griffiths, AndyKIDS 200 1356.. -

Militants and the Media: Partners in Terrorism?

Indiana Law Journal Volume 53 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 1977 Militants and the Media: Partners in Terrorism? William R. Catton Jr. Washington State University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Communications Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Catton, William R. Jr. (1977) "Militants and the Media: Partners in Terrorism?," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 53 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol53/iss4/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MILITANTS AND THE MEDIA: PARTNERS IN TERRORISM? WILLIAM R. CATTON, JR.* In March, 1977 in the Canary Islands, a KLM 747 and a Pan American 747 landed at Tenerife. They had been diverted from another airport where terrorist happened then to be interfering with flight operations. As the two jumbo jets prepared to resume their transoceanic flights, they collided on the foggy runway. Five hundred and eighty-one innocent traverlers met death in the firey mishap. That record toll for a commercial aviation disaster could have come four years earlier. In 1973 a comparable number of airline passengers might have been blasted out of the Italian sky to publicize grievances not necessarily shared by any of them but passionately felt by one of the groups of frustrated people so ubiquitous in the modem world. -

The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2013 The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace Randal Sean Harrison Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Communication Commons Copyright 2013 Randal Sean Harrison Recommended Citation Harrison, Randal Sean, "The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace", Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2013. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/666 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Communication Commons THE PROBLEMATIC OF PRIVACY IN THE NAMESPACE By Randal Sean Harrison A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In Rhetoric and Technical Communication MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Randal Sean Harrison This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Rhetoric and Technical Communication. Department of Humanities Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Daryl Slack Committee Member: Dr. Patty Sotirin Committee Member: Dr. Diane Shoos Committee Member: Dr. Charles Wallace Department Chair: Dr. Ronald Strickland I dedicate this work to my family for loving and supporting me, and for patiently bearing with a course of study that has kept me away from home far longer than I’d wished. I dedicate this also to my wife Shreya, without whose love and support I would have never completed this work. 4 Table of Contents Chapter 1. The Problematic of Privacy ........................................................................ 7 1.1 Privacy in Crisis ................................................................................................ -

![Alpha [Yearbook] 1939 Bridgewater State Teachers College](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5123/alpha-yearbook-1939-bridgewater-state-teachers-college-5245123.webp)

Alpha [Yearbook] 1939 Bridgewater State Teachers College

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State Yearbooks Campus Journals and Publications 1939 Alpha [Yearbook] 1939 Bridgewater State Teachers College Recommended Citation Bridgewater State Teachers College. (1939). Alpha [Yearbook] 1939. Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/yearbooks/39 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. wmm HlHMMlHBill » H *-•* 0:M 4T J \*&*L i?% £?*' *' w$ p P p 1 «U ^% w >*a '" .«• , . :, , ^^MaO K&W 1 ** T f^LflfcT^... •U 3fc~ — 1A V^ III 1 I I iff :;:::"" ^ ' u^.JBlte * ; § v 1^'*«ypj t. **^0,%* : " • : l«w - : , nn ** 1 ^ jf. * ' w « 'C-kM^ if J»> ^., fro* <&**«*- r John J. Kelly President ALPHA 1939 PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENTS OF THE STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE BRIDGEWATER • MASSACHUSETTS VOLUME NO. XLI Dedication to Martha M. Burnell To Miss Burnell, former principal of the Training School, we lovingly dedicate this forty-first volume of Alpha. Her life and personality have been and will continue to be an inspiration to all of us with whom she came in contact. We commemorate the various phases of her work by appro- priate plates for divisions of activities and organizations recorded in our book. To the Alpha Board: My teaching began in the State of Maine in the autumn months of 1887, after receiving my diploma from the Gorham State Normal School; thence on to a country school in the mountains of New Hampshire, and soon to Concord, its capital. During my short principalship of the Rumford School in Concord, I conceived the idea of further study, and was directed to the Bridgewater State Normal School—that glowing forge of education where Albert Gardner Boyden was principal. -

Title Author Description Copies Available

Title Author Description Copies Available Discover a world full of color in this delightful board book inspired by the works of legendary children's book author and A Little Book About Colors Leo Lionni's Friends 1 illustrator Leo Lionni. With sturdy pages and engaging artwork, this colorful book is perfect for boys and girls ages 0 to 3. Everybody sing along—because it's time to do-si-do in the barnyard with a high-spirited animal crew! From Boynton on Board, the bestselling series of board books, here is BARNYARD DANCE, with Sandra Boynton's twirling pigs, fiddle- Barnyard Dance! Sandra Boynton playing cows, and other unforgettable animals. Extra-big, extra-fat, and extra-fun, BARNYARD DANCE features lively 3 rhyming text and a die-cut cover that reveals the wacky characters inside. Guaranteed to get kids and adults stomping their feet. Giraffes Can't Dance is a touching tale of Gerald the giraffe, who wants nothing more than to dance. With crooked knees and thin legs, it's harder for a giraffe than you would think. Gerald is finally able to dance to his own tune when he gets some Giraffes Can't Dance Giles Andreae 3 encouraging words from an unlikely friend. With light-footed rhymes and high-stepping illustrations, this tale is gentle inspiration for every child with dreams of greatness. Beep! Beep! Beep! Meet Blue. A muddy country road is no match for this little pick up--that is, until he gets stuck while pushing a dump truck out of the muck. Luckily, Blue has made a pack of farm animal friends along his route. -

20XX #1 4,99 Image 20XX #2 4,99 Image 20XX #3 4,99

20XX #1 4,99 Image 20XX #2 4,99 Image 20XX #3 4,99 Image 20XX #4 4,99 Image 20XX #6 6,24 Image A MAN AMONG YE #3 4,99 Image ACTION COMICS #1007 COVER A REGULAR STEVE EPTING COVER 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1010 COVER A REGULAR STEVE EPTING COVER 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1023 COVER A REGULAR JOHN ROMITA JR & KLAUS JANSON COVER 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1024 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1024 L PARRILLO VARIANT ED 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1025 COVER A JOHN ROMITA JR 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1025 COVER B LUCIO PARRILLO VAR 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1026 COVER A JOHN ROMITA JR & KLAUS JANSON 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1026 COVER B LUCIO PARRILLO VAR 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1027 COVER A JOHN ROMITA JR & KLAUS JANSON 4,99 DC ACTION COMICS #1027 COVER B GARY FRANK CARD STOCK VAR 6,24 DC ADVENTUREMAN #1 2ND PRINT 4,99 Image ADVENTUREMAN #2 2ND PRINT 4,99 Image ADVENTUREMAN #4 4,99 Image ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #1 (OF 5) COVER A BALBI 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #2 (OF 5) COVER A BALBI 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #2 (OF 5) COVER B SIMONSON 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #3 (OF 5) COVER A BALBI 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #3 (OF 5) COVER B SIMONSON 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #4 (OF 5) COVER A BALBI 4,99 Dark Horse ALIEN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY #4 (OF 5) COVER B SIMONSON 4,99 Dark Horse ALPHA FLIGHT #1 FACSIMILE EDITION 6,24 Marvel ALTER EGO #165 12,44 ALTER EGO #166 12,44 AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #252 FACSIMILE EDITION NEW PRINT 4,99 Marvel AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #31 4,99 Marvel AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #347 FACSIMILE EDITION