How New York's Public Housing Fails the City's New Poor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have a Happy Halloween!

Vol. 34, No. 10 First Class U.S. Postage Paid — Permit No. 4119, New York, N.Y. 10007 October 2004 THIRD ANNUAL KIDS’ WALK IN THE BRONX Modernization Project at Whitman/Ingersoll music, and dance to greet the One of NYCHA’s Largest Capital Improvement Projects young walkers, warm them up and cheer them on along their mile and a half trek around the track. Then, after a healthful lunch, games and activities filled the afternoon, along with educational and informational materials and face painting by Harborview Arts Center Artist-Consultant and pro- fessional clown Mimi Martinez. “Do you want to have this kind of fun next summer?” NYCHA Vice Chairman Earl Andrews, Jr. asked the assembled young peo- ple. After the loud and unsurpris- ing positive response, Mr. Andrews promised that NYCHA would do everything it could to find the funds to make Kids’ Walk On August 13th, NYCHA’s Chairman Tino Hernandez joined res- happen again. That message was idents and elected officials for a tour through Ingersoll Houses, reinforced by Board Member highlighting four model apartments. Shown here (front row, left Young residents from NYCHA’s Summer Camp program pre- JoAnna Aniello, Deputy General to right) are Whitman Houses Resident Association President pare for their one-and-a-half mile walk in Van Cortlandt Park. Manager for Community Opera- Rosalind Williams, Ingersoll Relocation Vice-Chairwoman Gloria tions Hugh B. Spence, Assistant Collins, Ingersoll Relocation Committee Member Janie Williams, By Allan Leicht Deputy General Manager for Ingersoll Relocation Committee Chairwoman Veronica Obie, ids’ Walk 2004, NYCHA’s third annual summer children’s Community Operations Michelle and Ingersoll Houses Resident Association President Dorothy walkathon to promote physical recreation and combat obesity Pinnock, and Director of Citywide Berry. -

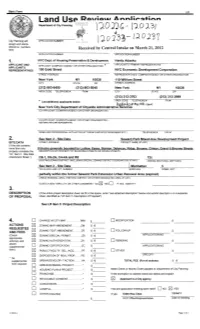

Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION B

Chapter 2, Section A: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION The project site is located in the Borough of Manhattan and includes the median malls on Allen Street between Delancey Street and East Broadway and on Pike Street between East Broadway and South Streets (sees Figure 2A-1). The Proposed Project would reconstruct the median mall sections to provide public green space, recreational space, and amenities, would improve the overall visual character of Allen and Pike Streets between Delancey and South Streets, and would serve as a gateway to the East River Esplanade from interior blocks. This section considers existing land use, zoning, and public land use policies for the project site and the surrounding 400-foot study area. Land use issues associated with the Proposed Project include potential changes in local land uses and neighborhood land use patterns. Zoning and public policy issues include the compatibility of the proposed modifications to the median malls with existing zoning and public policies. PRINCIPAL CONCLUSIONS As described below, this analysis concludes that the Proposed Project would be in keeping with and supportive of existing land uses in the study area, and that it would be consistent with zoning and public policy for the area. Overall, the Proposed Project would not result in any significant adverse impacts to land use, zoning or public policy. B. EXISTING CONDITIONS LAND USE PROJECT SITE The project site includes the Allen and Pike Street malls and the adjacent travel lanes. The Allen Street malls are located between Delancey Street and East Broadway. The Pike Street malls are located between East Broadway and South Street. -

July-2017-Nycha-Journal-En.Pdf

VOL. 47 NO. 5 JULY 2017 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 4 8 NextGen Digging in at Less energy, Neighborhoods Coney Island more comfort Breaking Ground on a New Future Al-tabar Hudgins SAFETY IS HIS MISSION Al-tabar Hudgins Is Walking the Talk MARINER’S HARBOR RESIDENT Al-tabar Hudgins, 23, is a young man with a mission to spread the word to his N JUNE 19, NYCHA launched con- Hurricane Sandy and other emergencies. peers about keeping themselves and struction work at Ocean Bay (Bayside) Residents will not have to move while their communities safe. O Apartments in Far Rockaway, a their apartments are being renovated, As a member of the Mayor’s Office of development that houses 3,700 residents. which should take about three years in total, Criminal Justice’s (MOCJ) Peer Leader- Under U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban instead of the 20 years it would have taken to ship Committee for the past three years, Development (HUD)’s Rental Assistance complete this work without PACT. Mr. Hudgins has been getting people Demonstration (RAD) program—known as “Through PACT, we are able to provide talking about gun violence. Peer leaders Permanent Affordability Commitment Togeth- our residents with the necessary repairs while are NYCHA residents under the age of er (PACT) in New York City—a new public- also preserving public housing for future 24 who receive training to become ad- private partnership will provide $325 million generations,” NYCHA Chair and CEO Shola vocates and activists for peace in their to renovate the development’s 24 buildings. -

NYCHA Celebrates Elliott-Chelsea Affordable Housing Opening by Zodet Negrón Close to Her Parents in NYCHA, but She Ew Construction in Manhattan’S Has Her Own Place

First-Class U.S. Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 NYCHA Vol. 42 No. 4 www.nyc.gov/nycha May 2012 NYCHA Celebrates Elliott-Chelsea Affordable Housing Opening By Zodet Negrón close to her parents in NYCHA, but she ew construction in Manhattan’s has her own place. NChelsea neighborhood received “I am happy to be able to stay in the great cheers from those who attended same neighborhood and have great new a ribbon-cutting ceremony on AprilJourna 3. neighbors in a nice, quiet brand-new l NYCHA Chairman John B. Rhea was building that I can afford,” said Vargas, a joined by Mathew Wambua, Com- single mother of two. “When I found out missioner of the NYC Department of I had all the requirements to qualify for Housing Preservation and Development this apartment, I was thrilled.” (HPD), Marc Jahr, President of the New Ms. Vargas describes her new living York City Housing Development Cor- situation as a totally different experience Nydia Mata, a former resident of Fulton Houses, stands in her kitchen with her son, Aidyn Mieles, and poration (HDC), and representatives of from NYCHA, and she is thankful to get her niece, Olivia Rodriguez, at the new Elliott-Chelsea affordable housing complex. Artimus Construction and Citi Commu- the opportunity to be there. nity Capital for the formal ribbon-cutting Nydia Mata, also a former resident of worked hard for this and now I have my opment was funded through public and ceremony of the Elliott-Chelsea, which the Fulton Houses, shares those senti- independence.” private partnerships, and is located on has 168 units of affordable housing for ments and also is glad to call Elliott- To date, 19 former NYCHA residents land that previously was used as a park- low- to middle-income families, includ- Chelsea her new home.“I used to live have moved into the new development ing lot by NYCHA for Elliott and Chelsea ing former NYCHA residents. -

Community Involvement in Redevelopment After the Expiration of Urban Renewal Plans

Renewing Renewal: Community Involvement in Redevelopment After the Expiration of Urban Renewal Plans A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Preservation COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning by Caroline Thompson May 2020 Abstract Communities impacted by urban renewal in the mid-twentieth century were largely unable to stop the changes brought to their neighborhoods. The plans that operationalized urban renewal remained in place for over 40 years, with significant legislative, legal, and financial effort required to make any alterations. In New York City, many of the urban renewal areas and their governing plans have since expired, ushering in market-driven development and neighborhood changes. This thesis uses a mixed-methods approach to analyze the subsequent built environment changes and to explore community involvement through case studies of redevelopment in the former Seward Park Extension Urban Renewal Area (SPEURA) and Two Bridges Urban Renewal Area (TBURA). While many lots remain unchanged since the urban renewal era, those that have changed reflect local development preferences or the results of major rezonings. The case studies reveal the wide variety of methods of community involvement in site redevelopment, with implications for future participation in redevelopment in the city. Key words: urban renewal, participation, Two Bridges, Essex Crossing, Large-Scale Developments ii Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... -

Zoning Text Amendment (ZR Sections 74-743 and 74-744) 3

UDAAP PROJECT SUMMARY Site BLOCK LOT ADDRESS Site 1 409 56 236 Broome Street Site 2 352 1 80 Essex Street Site 2 352 28 85 Norfolk Street Site 3 346 40 (p/o) 135-147 Delancey Street Site 4 346 40 (p/o) 153-163 Delancey Street Site 5 346 40 (p/o) 394-406 Grand Street Site 6 347 71 178 Broome Street Site 8 354 1 140 Essex Street Site 9 353 44 116 Delancey Street Site 10 354 12 121 Stanton Street 1. Land Use: Publicly-accessible open space, roads, and community facilities. Residential uses - Sites 1 – 10: up to 1,069,867 zoning floor area (zfa) - 900 units; LSGD (Sites 1 – 6) - 800 units. 50% market rate units. 50% affordable units: 10% middle income (approximately 131-165% AMI), 10% moderate income (approximately 60-130% AMI), 20% low income, 10% senior housing. Sufficient residential square footage will be set aside and reserved for residential use in order to develop 900 units. Commercial development: up to 755,468 zfa. If a fee ownership or leasehold interest in a portion of Site 2 (Block 352, Lots 1 and 28) is reacquired by the City for the purpose of the Essex Street Market, the use of said interest pursuant to a second disposition of that portion of Site 2 will be restricted solely to market uses and ancillary uses such as eating establishments. The disposition of Site 9 (Block 353, Lot 44) will be subject to the express covenant and condition that, until a new facility for the Essex Street Market has been developed and is available for use as a market, Site 9 will continue to be restricted to market uses. -

Resolution by Community Board 3

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] Alysha Lewis-Coleman, Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager September 2018 Vote Sheet Executive Committee no vote necessary Land Use, Zoning, Public & Private Housing Committee 1. Approval of previous month's minutes approved by committee 2. Borough President / Councilmember: Presentation on Text Amendment requiring Special Permit to modify Two Bridges LSRD VOTE: TITLE: Support for Council Member Chin and Manhattan Borough President Brewer's Text Amendment requiring a special permit to modify the Two Bridges Large Scale Residential Development (LSRD) WHEREAS, Council Member Margaret Chin and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer have filed an amendment to the New York City Zoning Resolution concerning Article VII, Chapter 8 (Special Regulations Applying to Large-Scale Residential Developments); and WHEREAS, the proposed zoning text amendment includes a provision requiring a special permit for modifications to the existing Two Bridges LSRD in Manhattan Community District 3; and WHEREAS, the requirement of a special permit for modifications to the Two Bridges LSRD would ensure that proposed changes to the underlying site planning and zoning controls that govern the LSRD would go through Uniform Land Use Review Procedures (ULURP), and be subject to review by the public, Community Board 3, the Manhattan Borough President, as well as review and approval by the New York City Council; -

NYCHA Journal.Qxd

First-Class U. S . Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 Vol. 39, No. 7 www.nyc.gov/nycha JULY 2009 From a High-Rise to the Highest Court Sonia Sotomayor, President Obama’s Nominee for Supreme Court Justice By Heidi Morales IF YOU'RE A NATIVE NEW YORKER form part of the highest court. OR PERHAPS A FAN OF THE NEW For the past 11 years, she has YORK YANKEES, THE NAME SONIA been a judge on the United SOTOMAYOR MAY HAVE SOUNDED States Court of Appeals for FAMILIAR TO YOU EVEN BEFORE the Second Circuit, based in SHE BECAME PRESIDENT BARACK New York City. OBAMA’S NOMINEE FOR U.S. Ms. Sotomayor, who is of Puerto Rican descent, was born SUPREME COURT JUSTICE. In 1995 in 1954 and grew up in the New Judge Sotomayor became as York City Housing Authority's legendary as baseball hall-of- (NYCHA's) Bronxdale Houses. famers for ending a long baseball Bronxdale Houses, located in the strike by ruling against owners in Bruckner section of the Bronx, DAY ONE (from left) NYCHA Board Member Margarita López, Deputy General Manager for favor of players. According to has 28 seven-story buildings with Ms. Sotomayor, the owners Finance Felix Lam, Citywide Council of Presidents Chair Reggie Bowman, NYCHA Chair John B. 1,496 apartments. Bronxdale is Rhea and City Council Member Alan Gerson at the Rutgers Houses in Manhattan on Chair were trying to destroy the labor home to approximately 3,500 Rhea’s first day on the job. residents. A modern, high-tech Community Center opened its NEW CHAIR VISITS FIVE BOROUGHS ON doors on the grounds of this development back in 2007, and offers educational and recre- WHIRLWIND, FIRST-DAY MEET-AND-GREET ational activities for children and By Howard Silver adults of the development and the surrounding community. -

Rutgers Slip

Phase 1A Archaeological Documentary Study Rutgers Slip Between Cherry and South Streets New York, New York Prepared for: Lower Manhattan Development Corporation One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor New York, NY 10006 Prepared by: AKRF, Inc. 440 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10016 May 2009 Management Summary SHPO Project Review Number: 06PR06649 LPC Project Review Number: HUD/106-M Involved Agencies: New York City Department of Parks and Recreation Lower Manhattan Development Corporation Phase of Survey: Phase 1A Archaeological Documentary Study Project Location: Rutgers Slip between Cherry and South Streets Minor Civil Division: 06101: Manhattan County: New York County Location Information: Survey Area Length: Approximately 375 feet (114.3 meters) Survey Area Width: Approximately 45 feet (13.7 meters) Number of Acres Surveyed: Approximately .4 USGS 7.5 Minute Quadrangle Map: Brooklyn Report Author: Elizabeth D. Meade, RPA Date of Report: May 2009 Table of Contents 1: Introduction A. Project Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 1 B. Research Goals and Methodology ................................................................................................................... 1 C. Site File Research Results ............................................................................................................................... 2 2: Environmental Setting A. Geology and Topography ............................................................................................................................... -

Testimony of State Senator Daniel Squadron Regarding the Draft Annual Plan 2013 for the New York City Housing Authority, July 25, 2012

RANKING MEMBER INVESTIGATIONS AND GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS THE SENATE SOCIAL SERVICES DANIEL SQUADRON STATE OF NEW YORK COMMITTEES SENATOR, 25TH DISTRICT CODES CONSUMER PROTECTION CORPORATIONS, AUTHORITIES & COMMISSIONS FINANCE JUDICIARY TRANSPORTATION TESTIMONY OF STATE SENATOR DANIEL SQUADRON REGARDING THE DRAFT ANNUAL PLAN 2013 FOR THE NEW YORK CITY HOUSING AUTHORITY, JULY 25, 2012. My name is Daniel Squadron and I represent the 25th Senate District in the New York State Senate. My district includes the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Vinegar Hill, Fulton Ferry, Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens and Gowanus, and the Manhattan neighborhoods of Tribeca, Battery Park City, the Lower East Side, Chinatown, the Financial District, Little Italy, SoHo and the East Village. Thank you for the opportunity to testify at this hearing. Among the New Yorkers that I represent are the residents of 24 New York City Housing Authority Developments, spanning the Lower East Side, East Village, Willamsburg, and Chinatown. The Manhattan part of my district includes the Bernard Baruch Houses, Marianna Bracetti Houses, Pedro Albizu Campos, East 4th Street Rehab, First Houses, Samuel Gompers Houses, Rafael Hernandez Houses, Fiorello H. LaGuardia Houses, Lower East Side I, II, and III, Lower East Side Rehab, Max Meltzer Tower, Jacob Riis Houses, Henry Rutgers Houses, Seward Park Extension, Alfred E. Smith Houses, Two Bridges, Vladeck Houses, Lillian Wald Houses, and 45 Allen Street. In Brooklyn, I represent three developments: the Taylor Street-Wythe Avenue Houses, Williams Plaza, and Independence Towers. My constituents experience firsthand the challenges described by the New York City Alliance to Preserve Public Housing, and that is why I generally support the recommendations listed in the Alliance’s NYCHA FY 2013 Draft Annual Plan Position Statement. -

Manhattan Location Address Program Status Closed

Grand St. Settlement COVID-19 Response and Status by Site Accurate as of March 16, 2020, 3:00pm Manhattan Location Address Program Status Closed. Staff working Early Head Start remotely. Afterschool Teen Center, Project SOL (LGBTQ Closed. Staff working Program) remotely. Computer Clubhouse Closed. Food distribution started. Tele-cosultation for Grand Coalition of Seniors Gompers Houses social services. Most 80 Pitt Street Community Center 80 Pitt Street 10002 staff working remotely. English as a Second Language Suspended Classes Group screening and workshops cancelled. Benefits Assistance: Benefits Modified schedules for Screening, Tax Preparation, Legal remote consultation Assistance, Financial Counseling only. Remote tax prep continues. Admin: Human Resources & IT Working remotely. Health, wellness and social services Closed until further for seniors notice. Tele- Vision Urban consultation for social Essex Crossing Community Center 175 Delancey Street 10002 Mencius Society for the Arts: services. Staff working remotely Executive Offices with staggered onsite schedule if needed. Modified for distance Job training program learning. GrandLo Café 168 Broome Street 10002 Closed until further Café notice. Closed until further Baruch Naturally Occurring Baruch Houses Baruch Elder Services Team for notice. Phone contact Retirement Community (NORC) 72 Columbia Street 10002 Senior Residents and tele-consultation for social services. Closed. Staff reporting on 3/17, 3/18, 3/19. Manhattan Child & Family Center Baruch Houses Afterwards, staff Head Start Head Start 294 Delancey Street 10002 working remotely and providing distance learning. Closed. Staff reporting Baruch Houses Manhattan Child & Family Center Child Care on 3/17, 3/18, 3/19. 300 Delancey Street 10002 Afterwards, staff working remotely and providing distance learning. -

THE CITY of NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4Th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 - [email protected]

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] Jamie Rogers, Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager FY'19 Capital Priorities 1. New K-8 school at Essex Crossing (DOE) Explanation: Eighty-five percent of Community School District 1 schools share a building with one or more schools, resulting in reduced access to gym, arts and enrichment, science labs, and acceptable hours for school lunch. With 1,000 new apartments slated for Essex Crossing by 2024, as well as the proposed development of over 3,000 additional units of housing in the Two Bridges neighborhood, there is a need for a new K through 8th grade school at Essex Crossing site 5. 2. Funding to continue constructing new park at Pier 42 (DPR) Explanation: This will be a destination park that will provide waterfront access with various amenities needed by the community. 3. Funding to construct remaining 7 malls of Allen Pike St Malls (DPR) Explanation: Six malls have been completed and seven malls remain to be reconstructed. This is a highly visible location, and currently unreconstructed malls attract garbage and derelict bikes. This has a negative impact on local businesses and does not address the lack of amenities needed by the community and tourists. Additionally, $2 million has been allocated for the Delancey Street Comfort Station. If this project does not move ahead, the Parks Department should reallocate the funding to the remaining malls. 4. Vladeck I and II: Mailboxes (NYCHA) Explanation: Upgrades to mailboxes will help ensure secure ease of access and privacy for NYCHA residents.