Uga Lab Series 3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

Cherokee Archaeological Landscapes As Community Action

CHEROKEE ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPES AS COMMUNITY ACTION Paisagens arqueológicas Cherokee como ação comunitária Kathryn Sampeck* Johi D. Griffin Jr.** ABSTRACT An ongoing, partnered program of research and education by the authors and other members of the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians contributes to economic development, education, and the creation of identities and communities. Landscape archaeology reveals how Cherokees navigated the pivotal and tumultuous 16th through early 18th centuries, a past muted or silenced in current education programs and history books. From a Cherokee perspective, our starting points are the principles of gadugi, which translates as “town” or “community,” and tohi, which translates as “balance.” Gadugi and tohi together are cornerstones of Cherokee identity. These seemingly abstract principles are archaeologically detectible: gadugi is well addressed by understanding the spatial relationships of the internal organization of the community; the network of relationships among towns and regional resources; artifact and ecofact traces of activities; and large-scale “non-site” features, such as roads and agricultural fields. We focus our research on a poorly understood but pivotal time in history: colonial encounters of the 16th through early 18th centuries. Archaeology plays a critical role in social justice and ethics in cultural landscape management by providing equitable access by * Associate Professor, Illinois State University, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Campus Box 4660, Normal, IL 61701. E-mail: [email protected] ** Historic Sites Keeper, Tribal Historic Preservation Office, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Qualla Boundary Reservation, P.O. Box 455, Cherokee, NC 28719, USA. História: Questões & Debates, Curitiba, volume 66, n.2, p. -

The Common Field Mississippian Site(23SG100), As Uncovered by the 1979 Mississippi River Flood Richard E

The Common Field Mississippian Site(23SG100), as Uncovered by the 1979 Mississippi River Flood Richard E. Martens Two of the pictures I took during an early visit to the he Common Field site occurs near the bluffs in the site are shown in Figure 1. The first shows Mound A, the TMississippi River floodplain 3 km south of St. Gen- largest of the six then-existing mounds. The nose of my evieve and approximately 90 km south of St. Louis. It is brand-new 1980 Volkswagen parked on the farm road is a large Mississippian-period site that once had as many as in the lower right corner of the picture. The second photo eight mounds (Bushnell 1914:666). It was long considered shows the outline of a burned house structure typical of to be an unoccupied civic-ceremonial center because very many evident across the site. Although it has been noted few surface artifacts were found. This all changed due that many people visited the site shortly after the flood, I to a flood in December 1979, when the Mississippi River did not meet anyone during several visits in 1980 and 1981. swept across the Common Field site. The resulting erosion I subsequently learned that Dr. Michael O’Brien led removed up to 40 cm of topsoil, exposing: a group of University of Missouri (MU) personnel in a [a] tremendous quantity of archaeological material limited survey and fieldwork activity in the spring of 1980. including ceramic plates, pots and other vessels, articu- The first phase entailed aerial photography (black-and- lated human burials, well defined structural remains white and false-color infrared) of the site. -

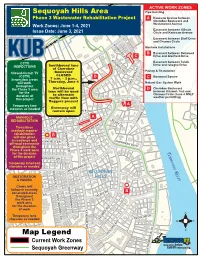

Sequoyah Hills Area Map Legend

NORTH BELLEMEADE AVE ACTIVE WORK ZONES Sequoyah Hills Area Pipe-bursting Phase 3 Wastewater Rehabilitation Project A Kenesaw Avenue between Cherokee Boulevard and Work Zones: June 1-4, 2021 Westerwood Avenue Easement between Hillvale Issue Date: June 3, 2021 KINGSTON PIKE Circle and Kenesaw Avenue Easement between Bluff Drive and Cheowa Circle BOXWOOD SQ Manhole Installations B Easement between Dellwood C Drive and Glenfield Drive KITUWAH TRL CCTV Easement between Talahi Southbound lane Drive and Iskagna Drive INSPECTIONS EAST HILLVALE TURN of Cherokee Paving & Restoration Closed-Circuit TV BoulevardWEST HILLVALE TURN CLOSED (CCTV) D C Boxwood Square Inspection crews 7 a.m. – 3 p.m., will work Thursday, June 4 Natural Gas System Work throughout LAKE VIEW DR the Phase 3 area Northbound D Cherokee Boulevard for the lane will be used between Kituwah Trail and to alternate Cheowa Circle (June 4 ONLY duration of weather permitting) this project traffic flow with flaggers present Temporary lane A closures as needed WOODHILLGreenway PL will remain openHILLVALE CIR MANHOLE A BLUFF DR REHABILITATION CHEOWA CIR Trenchless DELLWOOD DR manhole repairs/ OAKHURST DR KENESAW AVE TOWANDArehabilitation TRL B will take place in roadwaysSCENIC DR and GLENFIELD DR CHEROKEE BLVD off-road easements throughout the Phase 3 work zone Tennessee River for the duration of this project KENILWORTH DR Temporary lane/road closures as needed ALTA VISTA WAY WINDGATE ST ISKAGNA DR WOODLAND DR SEQUOYAH RESTORATION HILLS & PAVING Crews will EAST NOKOMIS CIR follow in recently B excavated areas WEST NOKOMIS CIR throughoutSAGWA DR TALAHI DR the Phase 3 work area SOUTHGATE RD for the duration of work KENESAW AVE TemporaryBLUFF VIEW RD lane closures as needed KEOWEE AVE TUGALOO DR W E S Map LegendAGAWELA AVE TALILUNA AVE Current Work Zones Sequoyah Greenway CHEROKEE BLVD. -

The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1923 The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763 David P. Buchanan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, David P., "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1923. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by David P. Buchanan entitled "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in . , Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: ARRAY(0x7f7024cfef58) Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) THE RELATIONS OF THE CHEROKEE Il.J'DIAUS WITH THE ENGLISH IN AMERICA PRIOR TO 1763. -

The Savannah River System L STEVENS CR

The upper reaches of the Bald Eagle river cut through Tallulah Gorge. LAKE TOXAWAY MIDDLE FORK The Seneca and Tugaloo Rivers come together near Hartwell, Georgia CASHIERS SAPPHIRE 0AKLAND TOXAWAY R. to form the Savannah River. From that point, the Savannah flows 300 GRIMSHAWES miles southeasterly to the Atlantic Ocean. The Watershed ROCK BOTTOM A ridge of high ground borders Fly fishermen catch trout on the every river system. This ridge Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers, COLLECTING encloses what is called a EASTATOE CR. SATOLAH tributaries of the Savannah in SYSTEM watershed. Beyond the ridge, LAKE Northeast Georgia. all water flows into another river RABUN BALD SUNSET JOCASSEE JOCASSEE system. Just as water in a bowl flows downward to a common MOUNTAIN CITY destination, all rivers, creeks, KEOWEE RIVER streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands SALEM and other types of water bodies TALLULAH R. CLAYTON PICKENS TAMASSEE in a watershed drain into the MOUNTAIN REST WOLF CR. river system. A watershed creates LAKE BURTON TIGER STEKOA CR. a natural community where CHATTOOGA RIVER ARIAIL every living thing has something WHETSTONE TRANSPORTING WILEY EASLEY SYSTEM in common – the source and SEED LAKEMONT SIX MILE LAKE GOLDEN CR. final disposition of their water. LAKE RABUN LONG CREEK LIBERTY CATEECHEE TALLULAH CHAUGA R. WALHALLA LAKE Tributary Network FALLS KEOWEE NORRIS One of the most surprising characteristics TUGALOO WEST UNION SIXMILE CR. DISPERSING LAKE of a river system is the intricate tributary SYSTEM COURTENAY NEWRY CENTRALEIGHTEENMILE CR. network that makes up the collecting YONAH TWELVEMILE CR. system. This detail does not show the TURNERVILLE LAKE RICHLAND UTICA A River System entire network, only a tiny portion of it. -

NINETY SIX to ABOUT YOUR VISIT Ninety Six Was Designated a National Historic National Historic Site • S.C

NINETY SIX To ABOUT YOUR VISIT Ninety Six was designated a national historic National Historic Site • S.C. site on August 16, 1976. While there Is much archaeological and historical study, planning and INDIANS AND COLONIAL TRAVELERS, A development yet to be done In this new area of CAMPSITE ON THE CHEROKEE PATH the National Park System, we welcome you to Ninety Six and Invite you to enjoy the activities which are now available. FRONTIER SETTLERS, A REGION OF RICH This powder horn is illustrated with the only known LAND, A TRADING CENTER AND A FORT map of Lieutenant Colonel Grant's 1761 campaign The mile-long Interpretive trail takes about FOR PROTECTION AGAINST INDIAN against the Cherokees. Although it is unsigned, the one hour to walk and Includes several strenuous ATTACK elaborate detail and accuracy of the engraving indicate that the powder horn was inscribed by a soldier, grades. The earthworks and archaeological probably an officer, who marched with the expedition. remains here are fragile. Please do not disturb or damage them. RESIDENTS OF THE NINETY SIX DISTRICT, A Grant, leading a force of 2,800 regular and provincial COURTHOUSE AND JAIL FOR THE ADMINI troops, marched from Charlestown northwestward along The site abounds In animal and plant life, STRATION OF JUSTICE the Cherokee Path to attack the Indian towns. An including poisonous snakes, poison oak and Ivy. advanced supply base was established at Ninety Six. We suggest that you stay on the trail. The Grant campaign destroyed 15 villages in June and July, 1761. This operation forced the Cherokees to sue The Ninety Six National Historic Site Is located PATRIOTS AND LOYALISTS IN THE REVOLU for peace, thus ending the French and Indian War on the on Highway S.C. -

To Jocassee Gorges Trust Fund

Jocassee Journal Information and News about the Jocassee Gorges Summer/Fall, 2000 Volume 1, Number 2 Developer donates $100,000 to Jocassee Gorges Trust Fund Upstate South Carolina developer Jim Anthony - whose things at Jocassee with the interest from development Cliffs at Keowee Vineyards is adjacent to the Jocassee the Trust Fund. Gorges - recently donated $100,000 to the Jocassee Gorges Trust “We are excited about Cliffs Fund. Communities becoming a partner with the “The job that the conservation community has done at Jocassee DNR on the Jocassee project,” Frampton Gorges has really inspired me,” said Anthony, president of Cliffs said. “Although there is a substantial Communities. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be here at amount of acreage protected in the the right time and to be able to help like this. We’re delighted to Jocassee Gorges, some development play a small part in maintaining the Jocassee Gorges tract.” around it is going to occur. The citizens John Frampton, assistant director for development and national in this state are fortunate to have a affairs with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, said developer like Jim Anthony whose Anthony’s donation will “jump-start the Trust Fund. This will be a conservation ethic is reflected in his living gift, because we will eventually be able to do many good properties. In the Cliffs Communities’ developments, a lot of the green space and key wildlife portions are preserved and enhanced. Jim Anthony has long been known as a conservationist, and this generous donation further illustrates his commitment to conservation and protection of these unique mountain habitats.” Approved in 1997 by the S.C. -

Jocassee Journal Information and News About the Jocassee Gorges

Jocassee Journal Information and News about the Jocassee Gorges www.dnr.sc.gov Fall/Winter 2020 Volume 21, Number 2 Wildflower sites in Jocassee Gorges were made possible by special funding from Duke Energy’s Habitat Enhancement Program. (SCDNR photo by Greg Lucas) Duke Energy funds colorful Jocassee pollinator plants Insects and hummingbirds South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) Jocassee Gorges Project Manager Mark Hall flocked to wildflower sites approached the HEP committee in 2019 with a proposal Several places within the Jocassee Gorges received a to establish wildflower patches throughout Jocassee Gorges colorful “facelift” in 2020, thanks to special funding through to benefit “pollinator species.” Pollinator species include Duke Energy’s Habitat Enhancement Program (HEP). bats, hummingbirds, bees, butterflies and As part of the Keowee-Toxaway relicensing other invertebrates that visit wildflowers and agreement related to Lakes Jocassee and Keowee, subsequently distribute pollen among a wide Duke Energy collects fees associated with docks range of fruit-bearing and seed-bearing plants. and distributes the monies each year for projects The fruits and seeds produced are eventually consumed within the respective watersheds to promote wildlife habitat by a host of game and non-game animals. Pollinator species improvements. Continued on page 2 Mark Hall, Jocassee Gorges Project land manager, admires some of the pollinator species that were planted in Jocassee Gorges earlier this year. (SCDNR photo by Cindy Thompson) Jocassee wildflower sites buzzing with life Continued from page 1 play a key role in the complex, ecological chain that is the is a very important endeavor. Several additional miles of foundation for diverse vegetation within Jocassee Gorges. -

Descendants of Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico

Descendants of Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico Generation 1 1. SMALLPOX CONJURER OF1 TELLICO . He died date Unknown. He married (1) AGANUNITSI MOYTOY. She was born about 1681. She died about 1758 in Cherokee, North Carolina, USA. He married (2) APRIL TKIKAMI HOP TURKEY. She was born in 1690 in Chota, City of Refuge, Cherokee Nation, Tennessee, USA. She died in 1744 in Upper Hiwasssee, Tennessee, USA. Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico and Aganunitsi Moytoy had the following children: 2. i. OSTENACO "OUTACITE" "USTANAKWA" "USTENAKA" "BIG HEAD" "MANKILLER OF KEOWEE" "SKIAGUSTA" "MANKILLER" "UTSIDIHI" "JUDD'S FRIEND was born in 1703. He died in 1780. 3. ii. KITEGISTA SKALIOSKEN was born about 1708 in Cherokee Nation East, Chota, Tennessee, USA. He died on 30 Sep 1792 in Buchanan's Station, Tennessee, Cherokee Nation East. He married (1) ANAWAILKA. She was born in Cherokee Nation East, Tennessee, USA. He married (2) USTEENOKOBAGAN. She was born about 1720 in Cherokee Nation East, Chota, Tennessee, USA. She died date Unknown. Notes for April Tkikami Hop Turkey: When April "Tikami" Hop was 3 years old her parents were murdered by Catawaba Raiders, and her and her 4 siblings were left there to die, because no one, would take them in. Pigeon Moytoy her aunt's husband, heard about this and went to Hiawassee and brought the children home to raise in the Cherokee Nation ( he was the Emperor of the Cherokee Nation, and also related to Cornstalk through his mother and his wife ). Visit WWW. My Carpenter Genealogy Smallpox Conjurer of Tellico and April Tkikami Hop Turkey had the following child: 4. -

Proquest Dissertations

Recalling Cahokia: Indigenous influences on English commercial expansion and imperial ascendancy in proprietary South Carolina, 1663-1721 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Wall, William Kevin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:16:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/298767 RECALLING CAHOKIA: INDIGENOUS INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH COMMERCIAL EXPANSION AND IMPERIAL ASCENDANCY IN PROPRIETARY SOUTH CAROLINA, 1663-1721. by William kevin wall A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES PROGRAM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 UMI Number: 3205471 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3205471 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

Vegetative Buffer Requirements: an Overview Oconee County Municipal Code 38-11.1

OCONEE COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA VEGETATIVE BUFFER REQUIREMENTS: AN OVERVIEW OCONEE COUNTY MUNICIPAL CODE 38-11.1 UPDATED JULY, 2017 OCONEE COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT This buffer is intended to protect water ance shall occur below the silt fence unless it quality, maintain natural beauty, and limit is deemed necessary by a certified arborist to secondary impacts of new development remove diseased trees. that may negatively affect the lifestyles of Dead trees may be removed with the ap- proval of the zoning administrator. those living near the lakeshore and the general enjoyment of the lakes by all citi- No trees larger than six-inch caliber at zens. four feet from the ground shall be re- moved unless certified to be a hazard by a A natural vegetative buffer shall be estab- registered forester or arborist. lished on all waterfront parcels of Lakes Jocassee and Keowee within 25 feet from Trees may be limbed up to 50 percent of the full pond level. Those parcels not meet- their height. A removal plan shall be sub- ing this criteria shall be exempt from this mitted for approval. standard. A view lane of no more than 15 percent of Full pond level is, 800 feet above mean sea the buffer area shall be permitted in the level on Lake Keowee, and 1,110 feet above natural buffer area (see back of this page). mean sea level on Lake Jocassee. Impervious surface no greater than 20 per- cent of the allowed view lane area is permit- The buffer shall extend to a depth of 25 feet ted.