Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HHH Collections Management Database V8.0

HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER NY-334 Extending 11.2 miles from West 72nd Street to Bronx-Westchester NY-334 border New York New York County New York WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER No. NY-334 LOCATION: The Henry Hudson Parkway extends from West 72nd Street in New York City, New York, 11.2 miles north to the beginning of the Saw Mill River Parkway at Westchester County, New York. The parkway runs along the Hudson River and links Manhattan and Bronx counties in New York City to the Hudson River Valley. DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1934-37 DESIGNERS: Henry Hudson Parkway Authority under direction of Robert Moses (Emil H. Praeger, Chief Engineer; Clinton F. Loyd, Chief of Architectural Design); New York City Department of Parks (William H. Latham, Park Engineer); New York State Department of Public Works (Joseph J. Darcy, District Engineer); New York Central System (J.W. Pfau, Chief Engineer) PRESENT OWNERS: New York State Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Parks and Recreation; Metropolitan Transit Authority; Amtrak; New York Port Authority PRESENT USE: The Henry Hudson Parkway is part of New York Route 9A and is a linear park and multi-modal scenic transportation corridor. Route 9A is restricted to non-commercial vehicles. Commuters use the parkway as a scenic and efficient alternative to the city’s expressways and local streets. Visitors use it as a gateway to Manhattan, while city residents use it to access the Hudson River Valley, located on either side of the Hudson River. -

New York Central RR High

West Side TKThe rise ? and fall of Manhattan s High Line by Joe Greenstein 1934: nearly complete, the two-track High Line will lift trains out of nearby Tenth Avenue. New York Central © 201 Kalmbach Publishing Co. This material may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. www.TrainsMag.com itm r* .. : 1 . 1 4tl * * ': 1* *'::. ,. * j ** % t * * m ? " '' % * m > wmg m ': ** ' f<P 4 5$ :f/Y ? \ if -\ fi n '% ft 2001: wildflowers grace the moribund High Line Al above Long Island's car yard at 30th Street. silent, an old rail road viaduct still winds its State-of-the-art St. John's Park Terminal way down Manhattan's West anchored the south end of the High Line. Side. Once a bustling New York Central freight line, it hasGhostlynot seen a train for 20 and of the railbank a federal to this years, conservancy, preserve unique vestige of Man most New Yorkers barely notice the program that converts unused rail hattan's industrial past. Indeed, in view drab structure. But the "High Line" has rights-of-way to recreational trails, with of recent catastrophic events here, the sparked an impassioned debate between the understanding that railroads may idea of paying homage to the city's it is an his reclaim them. In to those who think important someday opposition transportation history has taken on a is the Chelsea torical legacy worth preserving, and this idea Property Owners new poignancy. "It's a once-in-a-lifetime those who view it as an ugly impedi Group, which views the High Line as a opportunity," he said. -

Urban Catalyst Francin Supervised Research Project Submitted to Prof

URBAN CATALYST KATE-ISSIMA FRANCIN URBAN CATALYST Supervised Research Project Submitted to Prof. Raphaël Fichler School of Urban Planning McGill University May 2015 Cover page: Pathway on High Line in West Chelsea, between West 24th and West 25th Streets, looking South. Source: Iwan Baan,High Line Section 2 (2011) URBAN CATALYST By Kate-Issima Francin Supervised Research Project Submitted to: Professor Raphaël Fichler In partial fulfillment of the Masters of UrbanPlanning degree School of Urban Planning McGill University May 2015 ABSTRACT Figure 1. Section of High Line Park: Gansevoort Slow Stair i Source: Iwan Baan,The High Line Section 1, (2009). Land suitable for development has become be used, and the urban catalyst strategy as increasingly scarce and expensive in most a means of improving the physical conditions post-industrial North American and Euro- of an area, spurring urban change at a larger pean cities. As a result, underutilized areas scale and therefore improving the quality of that had previously been overlooked have life of individuals. The study concludes that become important assets in the urban de- well-thought and well-designed urban cat- velopment process, and planners must find alysts can promote quality urban design by alternative to traditional urban transformation connecting the old and the new, improving approaches which relied on massive public place identity, and stimulating more coher- investments. Urban catalysts appear to be ent development. Urban catalysts should be interesting tools to improve the quality of the at the core of a collaborative and integrated built environment, and hence, the quality of planning and design process. -

WEST CHELSEA HISTORIC DISTRICT Designation Report

WEST CHELSEA HISTORIC DISTRICT Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission July 15, 2008 Cover: Terminal Warehouse Company Central Stores (601 West 27th Street) (foreground), Starrett-Lehigh Building (601 West 26th Street) (background), by Christopher D. Brazee (2008). West Chelsea Historic District Designation Report Essay researched and written by Christopher D. Brazee & Jennifer L. Most Building Profiles & Architects’ Appendix by Christopher D. Brazee & Jennifer L. Most Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Stephen F. Byrns Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Joan Gerner Elizabeth Ryan Roberta Brandes Gratz Roberta Washington Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS WEST CHELSEA HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP........................................................................... 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 2 WEST CHELSEA HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ......................................................... 2 SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 4 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE WEST CHELSEA HISTORIC DISTRICT .................................................................................................................. -

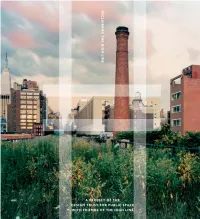

Reclaiming the High Line Is a Project of the Design Trust for Public Space, with Friends of the High Line

Reclaiming the High Line is a project of the Design Trust for Public Space, with Friends of the High Line. Design Trust Fellow: Casey Jones Writer: Joshua David Editor: Karen Hock Book design: Pentagram Design Trust for Public Space: 212-695-2432 www.designtrust.org Friends of the High Line: 212-606-3720 www.thehighline.org The Design Trust project was supported in part by a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. Printed by Ivy Hill Corporation, Warner Music Group, an AOL Time Warner Company. Cover photograph: “An Evening in July 2000” by Joel Sternfeld Title page photograph by Michael Syracuse Copyright 2002 by the Design Trust for Public Space, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechan- ical means without written permission from the Design Trust for Public Space, Inc. ISBN: 0-9716942-5-7 RECLAIMING THE HIGH LINE A PROJECT OF THE DESIGN TRUST FOR PUBLIC SPACE WITH FRIENDS OF THE HIGH LINE 1 1 . Rendering of the High Line 2 C ONTENTS FOREWORD 4 by New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg HIGH LINE MAP AND FACT SHEET 6 INTRODUCTION 8 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PUBLIC REUSE 17 Why Save the High Line? Recommendations for a Preserved, Reused High Line HISTORY OF THE HIGH LINE 44 Early Rail Transit West Side Improvement Decline of Rail Commerce The Call for Trail Reuse EXISTING CONDITIONS 56 Current Use Maintenance/Structural Integrity PHYSICAL CONTEXT 58 Zoning Surrounding Land Use Upcoming Development COMPETING OWNERSHIP PLANS 70 Demolition Efforts by Chelsea Property Owners Reuse Efforts by Friends of the High Line Political Climate EVALUATION OF REUSE OPTIONS 74 Demolition/Redevelopment Transit Reuse Commercial Reuse Open Space Reuse Moving Forward THE HIGH LINE AND THE CITY AS PALIMPSEST 82 by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers BIBLIOGRAPHY 84 PROJECT PARTICIPANTS 86 3 New York City would be unlivable without its parks, trees, and open spaces. -

Semiar 2 Research Paper

Rachel Ferrier Integrated Seminar 2 Professor Bakalarz 4/18/16 Research Paper “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”1 This quote by Jane Jacobs reveals the ever-changing cities based on its residents. Over the past 10 years2, the neighborhood of Chelsea in New York City has had an increase in gentrification, or a lack of diversity in the area, which began around the start of the construction of the High Line - a once historic elevated train track that is now a park that runs from 14th Street to 34th Street along 10th Avenue in Chelsea. Besides the art galleries, commercial businesses, and restaurants, it has been claimed that this increase in gentrification was caused by the construction of the High Line. Chelsea is known for its sustainability in historic architecture, using older buildings as modern day commercial chain stores and restaurants, and a prime example of this sustainability is the High Line. My proposed question is why specifically is the High Line considered a facet of Chelsea’s gentrification and what about the High Line contributed to the gentrification? The name "Chelsea" was chosen by Chelsea’s first landowner, Thomas Clarke, and named after the Royal Hospital Chelsea, a retirement home for soldiers in London, 1 Jacobs, Jane. “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” Random House, New York. 1961. 2 Anonymous former Chelsea resident. Interview by the author. Chelsea, New York City, N.Y. April 10th, 2016. England. The neighborhood continued to grow from this point for about thirty years, with many single family households and row houses. -

[email protected]

Volume 33 Spring–Summer 2004 Numbers 2–3 High Line n New York City a project is under way to save a historic built one of the largest transportation networks in North viaduct, all that remains of Manhattan’s only all-freight America, held two rail routes into Manhattan. In 1871 he con- railway. Now known as the High Line, it runs for 20 city solidated passenger operations on the east side, culminating at I blocks along the western edge of lower Manhattan Grand Central Depot, and dedicated the west-side line to freight. through the Chelsea neighborhood and the Gansevoort The West Side Freight Line was 13 miles long and ran between Meat Market district. Once an area of factories and warehouses, Spuyten Duyvil, just north of Manhattan, and St. John’s Park, Chelsea is now a vibrant neighborhood mixing art galleries and south of Canal Street. artists’ studios with residential lofts. The Gansevoort Meat It soon developed dense traffic even though it operated under Market, the city’s most recently designated historic district, still severe handicaps, the greatest of which were a lack of space for contains many meat processing businesses now interspersed with freight yards and the need to locate much of the track on Tenth nightclubs and restaurants. With the shadow of the High Line and Eleventh avenues. When the tracks were laid in the 1840s, overhead, these neighborhoods retain an industrial grittiness that much of the land was open fields. By the 1920s, the trains were many find appealing. sharing the avenues with pedestrians, horsedrawn wagons, and After merging several smaller railroads in the automobiles, and the conflicts became intolerable. -

Manhattan West Is Essentially a New City, a Remarkable, Multifaceted Neighborhood That’S Been Created There

Welcome to Manhattan West Manhattan West is a thriving community made up of state-of-the-art custom-designed office space, experiential retail, abundant green space, an amenity-rich residential tower and boutique, urban-format hotel. 2 The Lifeline of New York City Once home of the notorious “Death Avenue” rail lines and the Tenth Avenue Cowboys that kept pedestrians safe from these trains, the far west side entered the 20th century as a Wild West Industrial Landscape. The Hudson River Railroad gave way to the High Line in the 1930s and was known as “The Life Line of New York” – the route through which valuable raw materials were transported into Manhattan 3 The Lifeline of New York City In 2019, the innovators and tastemakers have replaced the industrialists of the 19th and 20th centuries as the next business titans. Manhattan West will usher in a return of the west side as the lifeline of New York City, bringing together thought-leadership, innovative retail, activated outdoor spaces and providing a platform for organizations to reach their highest potential 4 The Nexus of New York’s Night Out The rezoning of the Theater District along with the redevelopment of Chelsea Piers into an entertainment and recreation complex has Transformed the West Side Into a Destination for Experience. Manhattan West is positioned at the epicenter of experiences from arts to athletics. Uniquely positioned as the connection point between the theater district, the High Line, the Chelsea art galleries, the Culture Shed and Madison Square Garden, Manhattan West will be the destination for all of the audiences attending these events. -

The High Line: the Long and Winding Road

The High Line: The Long and Winding Road By Jerry Gottesman, founder and chairman of Edison Properties This is the story of how close one of the New York City’s most popular public spaces came to never existing. People began strolling along a small section of the High Line in the spring of 2008, and what was once a decaying, desolate viaduct is today a beautifully landscaped park that stretches 1.5 miles along Tenth Avenue in New York City. In just a short time, it has been transformed into an enormously popular public space, one that has helped revitalize a neighborhood in one of the world’s great cities and draws five million people annually. The historic plaques posted strategically on the High Line focus on the days when it was a functioning and useful way to move milk, meat, produce, and raw and manufactured goods by rail from the industrial west side of Manhattan to outlying areas. But no plaque tells what transpired from the time the last train operated in 1980 to the time two young men launched an advocacy group in 1999 that successfully turned the High Line into a public space. Why am I giving this account? Mainly so my grandchildren might learn from my experience. The High Line’s history will always be part of New York City’s lore, but in large part, it is also the untold story of political maneuverings, backroom deals, patience and persistence, and good fortune. Built to Move It begins in 1847, the year the original Madison Square Garden was built, when the City of New York authorized street-level railroad tracks down Manhattan’s west side to ship freight. -

Preserving the Former IRT Powerhouse

Preserving the Former IRT Powerhouse A Preservation Plan Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Historic Preservation placeholder Preserving the Former IRT Powerhouse A Preservation Plan 2009 Department of Historic Preservation of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Historic Preservation at Columbia University. Studio Advisor: Kate WOOD Studio Group: Gillian CONNELL Emilie EVANS Justin GREENAWALT Kate HUSBAND Tom RINALDI Barbara ZAY http://www.arch.columbia.edu/hp/ Preserving the Former IRT Powerhouse Preserving the Former IRT Powerhouse is a project of the Department of Historic Preservation of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Historic Preservation at Columbia University. Director: Andrew Scott Dolkart Studio Advisor: Kate Wood Studio Group: Gillian Connell Emilie Evans Justin Greenawalt Kate Husband Tom Rinaldi Barbara Zay http://www.arch.columbia.edu/hp/ Copyright 2009 by the Department of Historic Preservation of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Historic Preservation at Columbia University Opposite: The former IRT powerhouse viewed from the corner of Eleventh Avenue and West 58th Street, May 2009. Image Credits pp. 8-9: 1) Cudahy / Under the Sidewalks of New York; 2) New York in Pictures; 3) Power Plant Engineering; 4) MTA; 5) Architecture; 6) Interborough Rapid Transit; 7) NYPL; 8) NYPL; 9) NY Regional Plan 1931; 10) Friends of the High Line; 11) MSN Live Maps; 12) T. Rinaldi; 13) nycsubway.org; 14) West Side Highway DEIS 1974; 15) ConEdison / LPC; 16) Buttenweiser / Waterbound; 17) wikipedia.org / Arnold Reinhold; 18) Jasper Goldman / MAS; 19) T. Rinaldi; 20) Friends of the High Line Image Credits p. 10: 1) Metropolitan Railway E96th St. plant, The Electrical Engineer; 2) Manhattan Railway E74th St. -

Chapter 7: Historic Resources

Special West Chelsea District Rezoning and High Line Open Space EIS CHAPTER 7: HISTORIC RESOURCES A. INTRODUCTION The proposed action would not result in significant adverse impacts to archaeological resources; however, it has the potential to result in unmitigated significant adverse impacts to S/NR-eligible architectural resources due to demolition, conversions/expansions and/or construction-related activity. In addition, as described in Chapter 6, “Shadows,” the proposed action would result in unmitigated significant adverse shadow impacts to two architectural resources. This chapter assesses the potential effect of the proposed action on historic architectural and archaeological resources. The CEQR Technical Manual identifies historic resources as districts, buildings, structures, sites, and objects of historical, aesthetic, cultural, and archaeological importance. This includes designated NYC Landmarks; properties calendared for consideration as landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC); properties listed on the State/National Registers of Historic Places (S/NR) or contained within a district listed on or formally determined eligible for S/NR listing; properties recommended by the New York State Board for listing on the S/NR; National Historic Landmarks; and properties not identified by one of the programs listed above, but that meet their eligibility requirements. As discussed below, several designated and eligible historic resources and portions of three designated historic districts are located either within, or in the vicinity of, the proposed action area. Because the proposed action would generate development that could result in new in-ground disturbance and construction of a building type not currently permitted in the affected area, the proposed action has the potential to affect archaeological and architectural resources. -

October 18, 2019 Sarah Carroll, Chair Landmarks Preservation

CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD FOUR 330 West 42nd Street, 26th floor New York, NY 10036 tel: 212-736-4536 fax: 212-947-9512 www.nyc.gov/mcb4 BURT LAZARIN Chair JESSE R. BODINE District Manager October 18, 2019 Sarah Carroll, Chair Landmarks Preservation Commission Municipal Building, 9th floor One Centre Street New York, NY 10007 Re: 261 Eleventh Avenue – Terminal Warehouse Building Certificate of Appropriateness for Proposed Renovation & Modification Dear Chair Carroll: DistrictOn the Manager recommendation of its Chelsea Land Use Committee, following a duly noticed public hearing at the Committee's meeting on September 16, 2019, Manhattan Community Board 4 (CB4), at its regularly scheduled meeting on October 2, 2019, voted, by a vote of 35 in favor, 0 opposed, 1 abstaining, and 1 present but not eligible to vote, to recommend, with conditions, the approval of an application to the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) for a Certificate of Appropriateness for the proposed restoration and conversion of the Terminal Warehouse building into a modern office building with ground-floor retail. The Board’s conditions, set out in detail below, are largely based on its desire to see a more accurate, historic restoration of the eastern end of the building to balance the more modern restoration of the rest of the building. The Building The building, bounded by Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues and West 27th and West 28th Streets, is within the West Chelsea Historic District. It was built in 1891 as 25 separate “Stores,” with the odd-numbered Stores, 1 through 23, on West 27th Street and the even-numbered Stores, 2 through 26, on West 28th Street.