CIVIL WAR at 150

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2021 Community Services Directory

United Way of Northern Shenandoah Valley Community Services Directory 2019-2021 Visit us on the web at: www.unitedwaynsv.org @UWNSV 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Letter ............................................................................................................ 3 Alphabetical Index. ..................................................................................................... 4-10 Alphabetical Listing of Service Organizations ........................................................ 11-174 Toll-Free Directory .............................................................................................. 175-178 Service Index (Listings by Categories) ............................................................... 179-186 Listing of Food Pantries ...................................................................................... 187-190 Listing of Public Schools ..................................................................................... 191-195 2 United Way of Northern Shenandoah Valley COMMUNITY SERVICES DIRECTORY 2019-2021 Dear Neighbors: Across our region, medical emergencies, financial crises, and housing insecurities force families to make tough choices every day. The ability to meet basic needs, including access to safe housing, adequate food and medical care, provides stability for our community. Hundreds of nonprofits across our region are working to address these needs. This Community Resource Directory is a comprehensive guide to area non-profits and services. It contains information on over -

Confederate Forces at the Same Time

CHICAGO CIVIL WAR ROUNDTABLE SHENANDOAH VALLEY – 1864 Shenandoah Valley Map 1864 CHICAGO CIVIL WAR ROUNDTABLE SHENANDOAH VALLEY – 1864 Page 1 of 83 Table of Contents Shenandoah Valley Map 1864 ...................................................................................................................... 0 Shenandoah 1864 by Jonathan Sebastian .................................................................................................... 3 Lower Shenandoah Valley ............................................................................................................................. 9 Army of the Shenandoah ............................................................................................................................ 10 Army of the Valley....................................................................................................................................... 11 Maps ........................................................................................................................................................... 12 Overview Shenandoah Valley Campaigns May-June 1864 ..................................................................... 12 Battle of New Market Map 1 .................................................................................................................. 13 Battle of New Market Map 2 .................................................................................................................. 14 Battle of New Market Map 3 ................................................................................................................. -

General John Daniel Imboden Copyright

General John Daniel Imboden copyright: Lawrence J. Fleenor, Jr. June 2001 Big Stone Gap, Va. Few people are as of great an importance to the history of far Southwest Virginia as John D. Imboden. He and a few others transformed that region from the poverty stricken isolation of the post Civil War period into the modern industrial age. John Daniel Imboden was born on his family plantation near Staunton, Virginia on Feb. 16, 1823, the son of George William and Isabella Wunderlich Imboden. He attended Washington College, now called Washington and Lee, and after graduation taught school while he read law. After passing the bar, he opened a law office in Staunton, and used this as a base for his election twice to the General Assembly. After the bombardment of Fort Sumter President Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the rebellion of the southern states. Virginia called a secession convention instead, and Imboden was elected as a delegate to it, and voted for secession. He returned to Staunton where he used his prestige to raise the volunteer Staunton Artillery, and became its Captain. Together they fought at First Manassas, where he supported General Bee, who gave Stonewall Jackson his nickname during this battle. Later he captured the U. S. Arsenal at Harper's Ferry, and again demonstrated his recruiting abilities by raising the Partisan Rangers, which became the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry, and with which he fought at Cross Keys, New Market, and at Port Republic under Stonewall Jackson. He was on Early's Washington campaign. In January 1863 he became a Brigadier General and lead a raid into West Virginia where he cut the B & O Railroad, and confiscated the thousands of cattle and horses from local farmers which enabled Lee to take his Army of Northern Virginia into the Gettysburg Campaign. -

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A. Miller, ]r. '50A The contributions of Virginia Military Institute alumni in Confed dent. His class standing after a year-and-a-half at the Institute was erate service during the Civil War are well known. Over 92 percent a respectable eighteenth of twenty-five. Sharp, however, resigned of the almost two thousand who wore the cadet uniform also wore from the corps in June 1841, but the Institute's records do not Confederate gray. What is not commonly remembered is that show the reason. He married in early November 1842, and he and thirteen alumni served in the Union army and navy-and two his wife, Sarah Elizabeth (Rebeck), left Jonesville for Missouri in others, loyal to the Union, died in Confederate hands. Why these the following year. They settled at Danville, Montgomery County, men did not follow the overwhelming majority of their cadet where Sharp read for the law and set up his practice. He was comrades and classmates who chose to support the Common possibly postmaster in Danville, where he was considered an wealth and the South is not difficult to explain. Several of them important citizen. An active mason, he was the Danville delegate lived in the remote counties west of the Alleghenies where to the grand lodge in St. Louis. In 1859-1860 he represented his citizens had long felt estranged from the rest of the state. Citizens area of the state in the Missouri Senate. Sharp's political, frater of the west sought to dismember Virginia and establish their own nal, and professional prominence as well as his VMI military mountain state. -

Episode 210: Prelude to Cedar Creek Week of October 12-October 18

Episode 210: Prelude to Cedar Creek Week of October 12-October 18, 1864 When Ulysses Grant took over command of all United States armies, he devised a plan to totally annihilate the Confederacy from multiple directions. While Grant and George Meade attacked Robert E. Lee and pushed him back toward Richmond, William Tecumseh Sherman would invade Georgia, Nathaniel Banks would attack Mobile, Alabama and Franz Sigel would invade the Shenandoah Valley, the Confederacy’s “breadbasket”. The Valley Campaign did not start well for the Union as Sigel’s troops were defeated at New Market in May by a Confederate army that included VMI cadets. Sigel was replaced by David Hunter. Hunter resumed the offensive in early June and pushed the Confederates all the way up the valley to Lexington, where Hunter burned most of the VMI campus. Hunter then turned his sites on Lynchburg, but he was headed off there by reinforced Confederate troops under Jubal Early. On June 18, Hunter withdrew into West Virginia. Robert E. Lee, concerned about the lack of supplies and food that would result from Union control of the valley, ordered Early to go on the offensive. He also wanted Early to provide a diversion to relieve the pressure Lee was feeling from Grant’s offensive. Early moved down the valley with little Union opposition and in early July moved into Maryland, defeating a Union force at Frederick. From there he actually reached the outskirts of Washington, DC, fighting a battle that concerned Abraham Lincoln so much that he watched it in person. Not being able to make more progress, Early withdrew back into Virginia, where he defeated the Union again near Winchester at the Second Battle of Kernstown. -

German Immigrants in the Civil War”

“Social Studies / History Activity” “Impact of German Immigrants in the Civil War” Background "I goes to fight mit Sigel" was the rallying cry of Unionist German immigrants during the Civil War. It was in Missouri that ethnic prejudice and political rivalry between immigrants and native-born citizens of the state led to military action. In the 1840s and '50s, many German citizens left their homes in Europe seeking freedom and democracy in America. Thousands began their new lives in St. Louis, where they established a strong cultural identity, founding German language newspapers and social organizations. Yet Germans realized that in order to be accepted by their fellow Americans they would have to assimilate to American (or English) traditions and practices. German Americans also developed strong anti-slavery and pro-Union views, believing that free labor and democracy were in direct conflict with the traditions of the South and the southern desire to expand slavery into the territories. When the Republican Party chose Abraham Lincoln as its candidate in 1860, the politically active St. Louis Germans comprised nearly all of Lincoln's support in Democratic Missouri. Many of their fellow citizens, immigrants from Tennessee and Kentucky, viewed the German immigrants with suspicion. As the Civil War approached, a rift existed between the state's slaveholders who supported the Democratic Party, and the commercially minded German Republicans of metropolitan St. Louis. Labeled as "Dutchmen" (the English corruption of Deutsche) by the non-Germans of Missouri, they were subject to prejudice that would ultimately have significant effects on the course of the Civil War. -

February 2021 Meeting Highlights

BRUNSWICK CIVIL WAR ROUND TABLE MEETING – March 3 , 2021 “SIGEL & BRECKINRIDGE: LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP FROM THE BATTLE OF NEW MARKET” SPEAKER: Sarah Kay Bierle “If your actions inspire others to dream of more, learn more, do more and become more, you are a leader.” John Quincy Adams Some historians and writers make hasty claims about the meaning of battles, the competency of generals, and leadership. They make their statements as if handing down the unvarnished word from on high. Sarah Kay Bierle presented a refreshing change of pace with her conclusions about leadership of Generals Franz Sigel and Breckenridge. In her honesty she admitted that their leadership qualities were those that appealed to her. Her modesty and earnestness earned our trust and her effective use of the Zoom platform our admiration. Much fought over during the Civil War, the Shenandoah Valley drew Sigel and Breckenridge together so that Sigel could deny the Valley’s victuals and soldiers to Lee in Richmond, and Breckenridge could retain the supplies and reinforce Lee. Both men came with a history. Sigel, a German immigrant respected by the German community, came with a German military academy background, a firm belief in education, experience as a writer and recruiter who attracted many soldiers from the German-American community, and experience in numerous battles where he lost, but successfully lead orderly retreats, no small feat in the heat of battle. He could both organize units and lead them in training. Decisive decisions, not so much. He repeatedly lost encounters such as the German rebellion he fought for in Europe, the second Battle of Bull Run, Chancellorsville, and the Valley versus Stonewall Jackson. -

Friedrich Franz Karl Hecker, 1811–1881 Part II Kevin Kurdylo

Volume 19 No 2 • Summer 2010 Friedrich Franz Karl Hecker, 1811–1881 Part II Kevin Kurdylo As the 150th anniversary of the begin- was convinced that the contract of ning of the Civil War approaches, we the Union could not be broken by a will examine the role German-born minority of states,2 and he believed immigrants played during that histori- firmly that each man should take cal era. The first section of this article on Friedrich Hecker (Spring 2010) his place according to his abilities. examines his career in Europe before Because he felt Sigel was the more he came to this country. This section experienced and competent soldier, focuses on his activities in America. he was prepared to do his part as an infantryman if need be. There were ealizing that Lincoln’s elec- others, including some of his promi- tion as president meant an nent German-American friends, end to compromise on the who felt Hecker should lead his own Rissue of slavery, southern states began troops. to secede from the Union in the first In May of 1861, without Hecker’s months of 1861. Propelled by the knowledge (though capitalizing on same strong beliefs he held during his reputation), recruitment had be- the Revolution of 1848, the fifty-year- gun in Chicago for what was called Colonel Friedrich Hecker old Hecker answered Lincoln’s call the 1st Hecker Jäger [Hunter] Regi- to arms, and he crossed the Missis- ment, later known as the 24th Illinois and not enough privates, and a severe sippi River by rowboat to join Francis Volunteers, and Hecker was offered discipline problem, the latter exac- (Franz) Sigel’s 3rd Missouri Volunteer command of this regiment with the erbated by friction between Hecker Regiment—as a private.1 Hecker rank of colonel. -

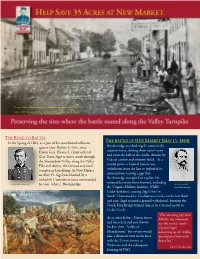

THE ROAD to BATTLE in the Spring of 1864, As a Part of His Coordinated

Town of New Market, looking south from the crossroads at the center of town, circa 1860. Courtesy New Market Area Library. THE ROAD TO BATTLE HE ATTLE OF EW ARKET AY In the Spring of 1864, as a part of his coordinated offensive T B N M (M 15, 1864) against Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army, Breckinridge attacked Sigel’s numerically superior force, driving them out of town Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered Gen. Franz Sigel to move south through and onto the hills to the north. Attacks by Federal cavalry and infantry failed. At a the Shenandoah Valley along the Valley Pike and destroy the railroad and canal crucial point, a Federal battery was withdrawn from the line to replenish its complex at Lynchburg. At New Market on May 15, Sigel was blocked by a ammunition, leaving a gap that Breckinridge was quick to exploit. He makeshift Confederate force commanded ordered his entire force forward, including Union Gen. Franz Sigel by Gen. John C. Breckinridge. Confederate Gen. the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) John C. Breckinridge “Lions of the Hour” by Keith Rocco, courtesy Tradition Studios Cadet Battalion, causing Sigel’s line to break. Threatened by Confederate cavalry on his left flank and rear, Sigel ordered a general withdrawal, burning the North Fork Bridge behind him as he retreated north to Cedar Creek. “This morning [at] New As so often before, Union forces Market, my command had been defeated and thrown met the enemy, under back in their “Valley of General Sigel, Humiliation,” but events would advancing up the Valley, take a dramatic turn weeks later and defeated him with with the Union victory at heavy loss.” Piedmont and the subsequent - John C. -

Concourse Mott Haven Melrose

Neighborhood Map ¯ Gerard Avenue 161 Bronx Bronx Railroad Bx41SBS e 199 County Hall Morrisania Air Rights g E 161 Street Criminal Park 908 d Bx6SBS Houses 897 ri Courthouse of Justice B Bx6SBS E 161 Street E 161 Street 271 Lou Gehrig Bx6SBS Bx6 331 m 3186 357 a Plaza Bx6SBS Bx6 SBS 399 D E 161 Street s Bx6SBS b E 161 Street m 58 86 Macombs o 868 Melrose c Bx6 Bx6 Dam Park a Job Center 860 M 161 St SBS Yankee Stadium Joseph Yancey 2 888 3158 861 Track and Field 860 859 863 Bx6 159 Park Avenue301 355 SBS CourtlandtAv 357 199 MelroseAv Bx6 Bx41SBS E 159 Street Concourse Village West E 160 Street Bx6 SBS Ruppert Place Gerard Avenue Bx6 Bx6 Walton Avenue Morrisania Macombs River Avenue Air Rights 828 83 Houses 3142 830 835 129 832 Dam Park 840 E 158 Street Bronx County Courthouse 821 835 Rainbow Block 301 90 Social Security 347 Association Garden 826 349 1 100 161 Concourse Plaza 828 Administration 399 199 3 River Avenue E 159 Street M E 158 Street a j Macombs Dam Bridge o 828 198 r D 800 3114 e River Avenue 273 813 808 e 805 E 157 St Parks 804 g 811 Family and a E 15 The Bat 8 Stre Friends Garden n 28 Smokestack et 295 355 E 272 798 399 800 401 x 131 p E 157 Street E 158 Street r 71 e s 118 s Morrisania Courtlandt Avenue 122 784 Concourse Village w 798 Air Rights Association a River Avenue Houses Garden y Parks 790 775 773 772 Concourse Village West E 153 Street Grand Concourse 355 Yankees-E 153 St CourtlandtAvenue 399 401 85 Metro-North Railroad Concourse E 157 Street MelroseAvenue 3076 773 201 Concourse VillageEast Jackson Houses 269 Park -

Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection (R0167)

Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection (R0167) Collection Number: R0167 Collection Title: Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection Dates: No date Creator: Unknown Abstract: The Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection contains photocopies of an unsigned memoir recounting the battle of Carthage in Jasper County, Missouri that took place on July 5, 1861. Contextual evidence indicates that the author might have been Archy Thomas, a soldier in the Missouri State Guard from Carollton, Missouri. Collection Size: 0.01 cubic foot (1 folder) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Rolla. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection (R0167); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Rolla [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Rolla]. Donor Information: The collection was donated to the University of Missouri by Susan F. Deatherage on May 20, 1983 (Accession No. RA0178). Related Materials: Additional materials related to the Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection can be found in the following collections: John T. Buegel Civil War Diary (C1844) (R0167) Carthage, Missouri Civil War Battle Collection Page 2 Processed by: Processed by John F. -

JAMES BRECKINRIDGE by Katherine Kennedy Mcnulty Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute A

JAMES BRECKINRIDGE by Katherine Kennedy McNulty Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF AR.TS in History APPROVED: Chairman: D~. George Green ShacJ;i'lford br. James I. Robertson, Jr. Dr. Weldon A. Brown July, 1970 Blacksburg, Virginia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to thank many persons who were most helpful in the writing of this thesis. Special thanks are due Dr. George Green Shackelford whose suggestions and helpful corrections enabled the paper to progress from a rough draft to the finished state. of Roanoke, Virginia, was most generous in making available Breckinridge family papers and in showing t Grove Hill heirlooms. The writer also wishes to thank of the Roanoke Historical Society for the use of the B' Ln- ridge and Preston papers and for other courtesies, and of the Office of the Clerk of the Court of Botetourt County for his help with Botetourt Records and for sharing his knowledge of the county and the Breckinridge family. Recognition is also due the staffs of the Newman Library of V.P.I.S.U., the Alderman Library of the University of Virginia, the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, and to the Military Department of the National Archives. Particular acknowledgment is made to the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia which made the award of its Graduate Fellowship in History at V.P.I.S.U. Lastly, the writer would like to thank her grandfather who has borne the cost of her education, and her husband who permitted her to remain in school and complete this degree.