Sterna Hirundo Linneaus Common Tern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Change in Common Tern (Sterna Hirundo) Nest Site Selection to Minimize Construction Related Disturbance

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Fish & Wildlife Publications US Fish & Wildlife Service 9-2019 Promoting Change in Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) Nest Site Selection to Minimize Construction Related Disturbance. Peter C. McGowan Jeffery D. Sullivan Carl R. Callahan William Schultz Jennifer L. Wall See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usfwspubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Fish & Wildlife Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Fish & Wildlife Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Peter C. McGowan, Jeffery D. Sullivan, Carl R. Callahan, William Schultz, Jennifer L. Wall, and Diann J. Prosser Table 2. The caloric values of seeds from selected Bowler, P.A. and M.E. Elvin. 2003. The vascular plant checklist for the wetland and upland vascular plant species in adjacent University of California Natural Reserve System’s San Joaquin habitats. Freshwater Marsh Reserve. Crossosoma 29:45−66. Clarke, C.B. 1977. Edible and Useful Plants of California. Berkeley, Calories in CA: University of California Press. Calories per Gram of seed 100 Grams Earle, F.R. and Q. Jones. 1962. Analyses of seed samples from 113 Wetland Vascular Plant Species plant families. Economic Botanist 16:221−231. Ambrosia psilolstachya (4.24 calories/g) 424 calories Ensminger, A.H., M.E. Ensminger, J.E. Konlande and J.R.K. Robson. Artemisia douglasiana (3.55 calories/g) 355 calories 1995. The Concise Encyclopedia of Foods and Nutrition. -

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Sterna Hirundo Linnaeus, 1758

Sterna hirundo Linnaeus, 1758 AphiaID: 137162 COMMON TERN Gnathostomata (Infrafilo) > Tetrapoda (Superclasse) > Laridae (Familia) Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Mai. 02 2013 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Mai. 04 2013 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 1 Jorge Araújo da Silva / Nov. 09 2011 Facilmente confundível com: Sternula albifrons Chlidonias niger Andorinha-do-mar-anã Gaivina-preta Sterna sandvicensis Garajau-comum Estatuto de Conservação Principais ameaças 2 Sinónimos Gaivina, Garajau (Madeira e Açores) Sterna fluviatilis Naumann, 1839 Referências Sepe, K. 2002. “Sterna hirundo” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed November 30, 2018 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sterna_hirundo/ BirdLife International. 2018. Sterna hirundo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22694623A132562687. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018 2.RLTS.T22694623A132562687.en original description Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata. Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae. ii, 824 pp., available online athttps://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.542 [details] additional source Cattrijsse, A.; Vincx, M. (2001). Biodiversity of the benthos and the avifauna of the Belgian coastal waters: summary of data collected between 1970 and 1998. Sustainable Management of the North Sea. Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs: Brussel, Belgium. 48 pp. [details] basis of record van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: the Importance of Artificial Sites

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: The Importance of Artificial Sites Jeremy J. Hatch Terns are familiar coastal birds in Massachusetts, nesting widely, but they are most numerous from Plymouth southwards. Their numbers have fluctuated over the years, and the history of the four principal species was compiled by Nisbet (1973 and in press). Two of these have nested in Boston Harbor: the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and the Least Tern (S. albifrons). In the late nineteenth century, the numbers of all terns declined profoundly throughout the Northeast because of intensive shooting of adults for the millinery trade (Doughty 1975), reaching their nadir in the 1890s (Nisbet 1973). Subsequently, numbers rebounded and reached a peak in the 1930s, declined again to the mid-1970s, then increased into the 1990s under vigilant protection (Blodget and Livingston 1996). In contrast, the first terns to nest in Boston Harbor in the twentieth century were not reported until 1968, and there are no records from the 1930s, when the numbers peaked statewide. For much of their subsequent existence the Common Terns have depended upon a sequence of artificial sites. This unusual history is the subject of this article. For successful breeding, terns require both an abimdant food supply and nesting sites safe from predators. Islands in estuaries can be ideal in both respects, and it is likely that terns were numerous in Boston Harbor in early times. There is no direct evidence for — or against — this surmise, but one of the former islands now lying beneath Logan Airport was called Bird Island (Fig. 1) and, like others similarly named, may well have been the site of a tern colony in colonial times. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Mute Swan (Cygnus Olor) ERSS

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2011 Revised, November 2018, March 2019 Web Version, 8/16/2019 Photo: Nolasco Diaz. Licensed under CC BY-SA. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cisne_por_la_noche.jpg. (11/28/2018). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range According to GISD (2018), Cygnus olor is native to Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Europe, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Korea, Democratic People's Republic Of Korea, Republic Of Latvia, Lithuania, Republic Of Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia And Montenegro, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom. 1 From BirdLife International (2018): “NATIVE Extant (breeding) Kazakhstan; Mongolia; Russian Federation (Eastern Asian Russia); Turkmenistan Extant (non-breeding) Afghanistan; Armenia; Cyprus; Iran, Islamic Republic of; Iraq; Korea, Republic of; Kyrgyzstan; Spain Extant (passage) Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Extant (resident) Albania; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Croatia; Czech Republic; Greece; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Liechtenstein; Luxembourg; Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of; Montenegro; Netherlands; Russian Federation; Serbia; Slovenia; Switzerland; Turkey; United Kingdom Extant Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; China; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; -

California Least Tern (Sternula Antillarum Browni)

California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation u.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, California September 2006 5-YEARREVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1 1.1. REVIEWERS 1 1.2. METHODOLOGY USED TO COMPLETE THE REVIEW: 1 1.3. BACKGROUND: 1 2. REVIEW ANALYSIS 2 2.1. ApPLICATION OF THE 1996 DISTINCT POPULATION SEGMENT (DPS) POLICY 2 2.2. RECOVERY CRITERIA 2 2.3. UPDATED INFORMATION AND CURRENT SPECIES STATUS 5 2.4. SyNTHESIS 22 3. RESULTS 22 3.1. RECOMMENDED CLASSIFICATION 22 3.2. NEW RECOVERY PRIORITY NUMBER 22 3.3. LISTING AND RECLASSIFICATION PRIORITY NUMBER, IF RECLASSIFICATION IS RECOMMENDED 23 4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIONS 23 5.0 REFERENCES •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 11 5-YEAR REVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1. Reviewers Lead Region: Diane Elam and Mary Grim, California-Nevada Operations Office, 916- 414-6464 Lead Field Office: Jim A. Bartel, Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Service, 760-431-9440 1.2. Metnodoiogy used to complete the review: This review was compiled by staffofthe Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office (CFWO). The review was completed using documents from office files as well as available literature on the California least tern. 1.3. Background: 1.3.1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: The notice announcing the initiation ofthis 5-year review and opening ofthe first comment period for 60 days was published on July 7, 2005 (70 FR 39327). A notice reopening the comment period for 60 days was published on November 3, 2005 (70 FR 66842). -

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

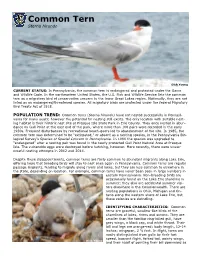

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management.