Directing Margaret Atwood's the Penelopiad in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenge of the Maids' Gyn/Affection in Margaret Atwood's

Vol. 7 (2015) | pp. 19-34 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_AMAL.2015.v7.47697 ‘CLOSE AS A KISS’: THE CHALLENGE OF THE MAIDS’ GYN/AFFECTION IN MARGARET ATWOOD’S THE PENELOPIAD GERARDO RODRÍGUEZ SALAS UNIVERSIDAD DE GRANADA [email protected] https://sites.google.com/site/gerardougr Article received on 14.01.2015 Accepted on 02.09.2015 ABSTRACT Margaret Atwood’s novella The Penelopiad (2005) seemingly celebrates Penelope’s agency in opposition to Homer’s myth in The Odyssey. However, the twelve murdered maids steal the book to suggest the possibility of what Janice Raymond calls gyn/affection, a female bonding based on the logic of emotion that, in Atwood’s revision, verges on Kristevan abjection, the sinister and the fantastic, and serves a cathartic effect not only in the maids but also in the reader. This essay aims to question the generally accepted empowerment of Atwood’s Penelope and celebrates the murdered maids as the locus of emotion, where marginal aspects of gender and class merge to weave a powerful metaphorical tapestry of popular and traditionally feminized literary genres that, in plunging into and embracing the semiotic realm, ultimately solidify into an eclectic but compact alternative tradition of women’s writing and myth-making. KEYWORDS Margaret Atwood, Penelopiad, Myth, Odyssey, Female friendship, gyn/affection, hetero-reality. ‘CERCANAS COMO UN BESO’: EL DESAFÍO DE LA AFECTIVIDAD FEMENINA DE LAS DONCELLAS EN THE PENELOPIAD DE MARGARET ATWOOD RESUMEN La novela de Margaret Atwood, The Penelopiad (2005), celebra en apariencia la agencia de Penélope frente al mítico personaje femenino de la versión de Homero. -

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10 Issue No Date Main Articles Workroom Process ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 1 Apr-Jun 1999 Luton - Ascot Shoot - Sean Barratt Feathers - Dawn Bassam -Trade Shows - Fashion Museums & Dillon Wallwork ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 2 Jul-Sep 1999 Paris – Marie O’Regan – Royal Ascot Working with crinn with - Student Shows – Geoff Roberts Frederick Fox ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 3 Oct-Nov 1999 Hat Designer of the Year ’99 - Block Making with Men in Hats, shoot – Trade Fairs Serafina Grafton-Beaves ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2000 Mitzi Lorenz – Philip Treacy couture Working with sinamay (1) show Paris – Florence – Bridal shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page – Trades Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 5 Apr-Jun 2000 Coco Chanel – Trade Fairs Working with sinamay (2) Dagmara Childs – Knits Shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page - Trade Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 6 Jul-Sep 2000 Luton shoot – Royal Ascot Working with -

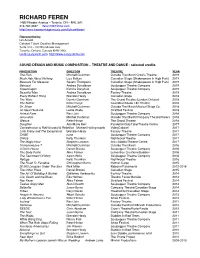

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, on – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected]

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, ON – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected] http://www.haemorrhage-music.com/richard-feren/ Represented by: Ian Arnold Catalyst Talent Creative Management Suite 310 - 100 Broadview Ave Toronto, Ontario Canada M4M 3H3 [email protected] http://www.catalysttcm.com SOUND DESIGN AND MUSIC COMPOSITION – THEATRE AND DANCE - selected credits PRODUCTION DIRECTOR THEATRE YEAR The Flick Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Crow’s Theatre 2019 Much Ado About Nothing Liza Balkan Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Measure For Measure Severn Thompson Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Betrayal Andrea Donaldson Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Copenhagen Katrina Darychuk Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Beautiful Man Andrea Donaldson Factory Theatre 2019 Every Brilliant Thing Brendan Healy Canadian Stage 2018 The Wars Dennis Garnhum The Grand Theatre (London Ontario) 2018 The Nether Peter Pasyk Coal Mine/Studio 180 Theatre 2018 Dr. Silver Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Musical Stage Co. 2018 An Ideal Husband Lezlie Wade Stratford Festival 2018 Animal Farm Ravi Jain Soulpepper Theatre Company 2018 Jerusalem Mitchel Cushman Outside The March/Company Theatre/Crow’s 2018 Silence Peter Hinton The Grand Theatre 2018 Daughter Ann-Marie Kerr Pandemic/QuipTake/Theatre Centre 2017 Confederation & Riel/Scandal & Rebellion Michael Hollingsworth VideoCabaret 2017 Little Pretty and The Exceptional Brendan Healy Factory Theatre 2017 CAGE none Soulpepper Theatre Company 2017 Unholy Kelly Thornton -

Star Wars: the Fascism Awakens Representation and Its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia

STAR WARS: THE FASCISM AWAKENS 7 Star Wars: The Fascism Awakens Representation and its Failure from the Weimar Republic to the Galactic Senate Chapman Rackaway University of West Georgia Whether in science fiction or the establishment of an earthly democracy, constitutional design matters especially in the realm of representation. Democracies, no matter how strong or fragile, can fail under the influence of a poorly constructed representation plan. Two strong examples of representational failure emerge from the post-WWI Weimar Republic and the Galactic Republic’s Senate from the Star Wars saga. Both legislatures featured a combination of overbroad representation without minimum thresholds for minor parties to be elected to the legislature and multiple non- citizen constituencies represented in the body. As a result both the Weimar Reichstag and the Galactic Senate fell prey to a power-hungry manipulating zealot who used the divisions within their legislature to accumulate power. As a result, both democracies failed and became tyrannical governments under despotic leaders who eventually would be removed but only after wars of massive casualties. Representation matters, and both the Weimer legislature and Galactic Senate show the problems in designing democratic governments to fairly represent diverse populations while simultaneously limiting the ability of fringe groups to emerge. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of representative democracies. A poor evil is for good men to do nothing.” constitutional design can even lead to tyranny. – Edmund Burke (1848) Among the flaws most potentially damaging to a republic is a faulty representational “So this is how liberty dies … with structure. Republics can actually build too thunderous applause.” - Padme Amidala (Star much representation into their structures, the Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith, 2005) result of which is tyranny as a byproduct of democratic failure. -

Hat Makers with Attitude - Nytimes.Com

Hat Makers With Attitude - NYTimes.com HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Log In Register Now Help Search All NYTimes.com WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS FASHION & STYLE DINING & WINE HOME & GARDEN WEDDINGS/CELEBRATIONS T MAGAZINE Millinery Madness: Hat Makers With Attitude Log in to see what your friends are sharing Log In With Facebook on nytimes.com. Privacy Policy | What’s This? What’s Popular Now Backlash by the With Extra Bay: Tech Riches Anchovies, Alter a City Deluxe Whale Watching Morgan White, Derek John, Justin Smith Hat-makers with attitude: Piers Atkinson, House of Flora and J Smith Esq. By ROBB YOUNG Published: October 3, 2011 They are not the sort of hat makers whose idea of topping off an outfit RECOMMEND involves a charming little cloche or a cozy beret. Some are hell-raising TWITTER provocateurs while others are more like cheeky jesters full of LINKEDIN merrymaking and mischief. A few are die-hard design intellectuals, SIGN IN TO E-MAIL and at least one literally blurs the boundaries between hats and the PRINT hair that they cover. But one thing that unites this motley crew of SINGLE PAGE modern milliners is that “restraint” and “simplicity” are not part of their vocabularies. REPRINTS SHARE “To borrow a phrase from the stylist The Collection: A Fashion Simon Foxton, ‘There’s nothing worse App for the iPad A one-stop than a jaunty trilby,”’ says Fred Butler, destination for an exuberant British accessories Times fashion coverage and the designer who got her big break when latest from the Lady Gaga’s stylist, Nicola Formichetti, commissioned the runways. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Rhubarb Festival

2020 22, – Festival sponsor FEBRUARY 12 FEBRUARY Buddies in Bad Times Theatre presents THE RHUBARB FESTIVAL Rhubarb2020-Brochure-V5.indd 1 2020-01-20 12:15 PM About Rhubarb Canada’s longest-running new works festival transforms Buddies into a hotbed of experimentation, with artists exploring new possibilities in theatre, dance, music, and performance art. Back this year for its 41st edition, Rhubarb is the place to see the most adventurous ideas in performance and to catch your favourite artists venturing into uncharted territory. Buddies in Bad Times Theatre is situated on the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee, the Anishinaabe, and the Wendat, and the treaty territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit. We acknowledge them and any other Nations who care for the land (acknowledged and unacknowledged, recorded and unrecorded) as the past, present and future caretakers of this land, referred to as Tkaronto (“Where The Trees Meet The Water”; “The Gathering Place”). Buddies is honoured to be a home for queer, trans and 2-Spirit artists on these storied and sacred lands that have been stewarded by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years before the arrival of colonial settlers. Rhubarb2020-Brochure-V5.indd 2 2020-01-20 12:15 PM A Message from the Curatorial Collective An entire continent is on fire, Facebook’s immovable ad policy now determines truth in politics, and this country’s ongoing project of genocide continues. The inexorable truth of democracy? Progress comes slowly. But, this is Rhubarb. And for the 41st festival, we begin with an offering. Of and for the future. -

Buddies in Bad Times Announces Programming for 2016/17 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, APRIL 19, 2016 Media Contact: Mark Aikman [email protected] 416.975.9130 x40 BUDDIES IN BAD TIMES ANNOUNCES PROGRAMMING FOR 2016/17 SEASON BUDDIESINBADTIMES.COM/SEASON – TICKETS ON SALE NOW TORONTO: April 19, 2016. Artistic Director Evalyn Parry announced an exciting line up for Buddies in Bad Times Theatre’s 2016/17 Season today. Parry’s first programmed season presents a series of engaging, timely productions that invite new conversations and perspectives onto Buddies stage. The season includes a queer spin on a hit improv comedy, the world premiere of a multidisciplinary project developed in the Buddies Residency Program, and a community-driven theatre project directed by Parry. The company also welcomes back a number of guest companies throughout the season. In announcing the season, Parry remarks: “I am thrilled to present a season that’s full of risky new creation, in conversation with classics of the modern stage. For me, queer theatre is about challenging form as well as content: finding new ways for our theatre to engage with and reflect our community. I look forward to inviting the community onto our stage – both literally and figuratively – this season.” Following sold out runs across North America, Rebecca Northan brings her hit show Blind Date to Buddies to kick off the mainstage season in September. Blind Date pairs a sexy clown with a willing audience member for a 90-minute, improvised show, starting with the titular blind date, then skillfully maneuvering through the evening in a “perfect marriage of theatre and comedy”. This re-imagined version of the play, being developed specifically for Buddies by Northan in collaboration with Evalyn Parry, explores queer romance for the first time. -

Another Penelope: Margaret Atwood's the Penelopiad

Monica Bottez ANOTHER PENELOPE: MARGARET ATWOOD’S THE PENELOPIAD Keywords: epic; quest; hybrid genre; indeterminacy; postmodernism Abstract: The paper sets out to present The Penelopiad as a rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey with Penelope as the narrator. Using the Homeric intertext as well as other Greek sources collected by Robert Graves in his book The Greek Myths and Tennyson‟s “Ulysses,” it evidences the additions that the new narrative perspective has stimulated Atwood to imagine. The Penelopiad is read as propounding a new genre, the female epic or romance where the heroine’s quest is analysed on analogy with the traditional romance pattern. The paper dwells on the contradictory and parody- like versions of events and characters embedded in the text: has Penelope been the perfect patient devoted wife, a cunning lustful pretender, or the High Priestess of an Artemis cult? In conclusion, the reader can never know the truth, being tied up in the utterly puzzling indeterminacy of meaning specific to postmodernism. The title of Margaret Atwood‟s novella makes the reader expect a rewriting of Homer‟s Odyssey, which is precisely what the author does in order to enrich it with new interpretations; since myths and legends are the repository of our collective desires, fears and longings, their actuality can never be exhausted: Atwood has used mythology in much the same way she has used other intertexts like folk tales, fairy tales, and legends, replaying the old stories in new contexts and from different perspectives – frequently from a woman‟s point of view – so that the stories shimmer with new meanings. -

Mothering and Work/ Mothering As Work

A YORK UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION MOTHERING AND WORK/ MOTHERING AS WORK Fallminter 2004 Volume6, Number 2 $15 Featuring articles by JaneMaree Maher, Debra Langan, Lorna Turnbull, Merlinda Weinberg, Alice Home, Naomi Bromberg Bar-Yam, Chris Bobel, Kate Connolly, Maryanne Dever and Lise Saugeres, Corinne Rusch-Drutz, Orit Avishai, Susan Schalge, Kelly C. Walter Carney and many more ... Mothering and Work/ Mothering as Work FalVWinter 2004 Volume 6, Number 2 Founding Editor and Editor-in-Chief Andrea O'Reilly Advisory Board Patricia Bell-Scott, Mary Kay Blakely, Paula Caplan, Patrice DiQuinzio, Miriam Edelson, Miriam Johnson, Carolyn Mitchell, Joanna Radbord, Sara Ruddick, Lori Saint-Martin Literary Editor Rishma Dunlop Book Review Editor Ruth Panofsb Managing Editor Cheryl Dobinson Guest Editorial Board Katherine Bischoping Deborah Davidson Debra Langan Andrea O'Reilly Production Editor Luciana Ricciutelli Proofreader Randy Chase Association for Research on Mothering Atkinson Faculty of Liberal and Professional Studies, 726 Atkinson, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON M3J 1P3 Tel: (416) 736-2100 ext. 60366 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.yorku.ca~crm TheJournal of the Association for Research on Mothering (ISSN 1488-0989) is published by The Association for Research on Mothering (ARM) The Association for Research on Mothering (ARM)is the first feminist organization devoted specifically to the topics of mothering and motherhood. ARM is an association of scholars, writers, activists, policy makers, educators, parents, and artists. ARM is housed at Atkinson College, York University, Toronto, Ontario. Our mandate is to provide a forum for the discussion and dissemination of feminist, academic, and community grassroots research, theory, and praxis on mothering and motherhood. -

Alice in Wonderland Set & Costume

Alice in Wonderland Set & costume For more information about Alice in Wonderland set & costume rental contact Production Manager Josh Neckels at 541 485 3992. [email protected] 1 SET PIECES 2 pieces Backdrop with scrim center for projection 1 center small piece backdrop (plays up stage of 2 piece back drop) Grass units 5 Doors (1 with pyro, 3 with Alice photos) 1 Key hole Revolving Alice Photo Boat w. punt oar Mushroom 3 Rose briar units 1 large tea pot Mock Turtle set piece Falling cards 2 COSTUMES Father William Fat suit, pants, shirt, waistcoat, jacket, mask Young Man Pants, shirt, jacket hat Caterpillar Black unitard caterpillar costume 3 COSTUMES The Mock Turtle Shirt, pants, soft sculpture shell, mask Gryphon Yellow/brown unitard with wings & tail, 1/2 mask with beak 2 Lobsters Red unitard (door movers) blue jackets, pink lobster head & pink claws 4 COSTUMES The Mad Hatter Pants, shirt, jacket, socks, top hat The Dormouse red/brown unitard, mask The March Hare Yellow unitard, Jacket, mask Tea Table Soft sculpture tea table with tea pot, cups & saucers (dancers under table with elastic support "wear table" ) 5 COSTUMES Fish Footmen Black unitards, jackets, masks The Cook Tights, dress, hat, nose piece The Duchess Tights, Dress, mask 6 COSTUMES Dodo Blue unitard and large foam body piece Mouse Grey unitard, mask Eaglet Green/yellow unitard with wings, mask 7 COSTUMES Eaglet Green/yellow unitard with wings, mask Duck White unitard with wings, mask Marten Blue unitard with tail, mask 8 COSTUMES Flamingos Pink unitards with wings, -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible.