De Lacey, Alex. 2020. 'Wot Do U Call It? Doof Doof': Articulations Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics

LEXICON Volume 5, Number 1, April 2018, 84-94 Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics Tessa Zelyana Hidayat*, Rio Rini Diah Moehkardi Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research examines semantic changes and also the associative patterns of slang, focusing primarily on common topics, i.e., people and drugs. The data were slang terms taken from the lyrics of hip-hop/rap songs sung by four singers, two from the U.S.A and two from the U.K. A total of 105 slang terms were found, 45 of which belong to the people category and 16 to the drugs category in the American hip-hop/rap song lyrics, and in the British hip-hop/rap song lyrics, 26 of which belong to the people category and 18 to the drugs category. Bitch and nigga were found to be the most frequently used slang terms in the people category. In terms of semantic changes, broadening, amelioration, and narrowing were found, and in terms of associative patterns, effect, appearance, way of consuming, constituent, and container associative patterns were found. In addition, a new associative pattern was found, i.e., place of origin. Keywords: associative patterns, people and drugs slang, semantic change, slang. mislead people outside their group. Then, the INTRODUCTION usage of Cant began to slowly develop. Larger “This party is just unreal!” Imagine a person groups started to talk Cant in their daily life. It saying this sentence in the biggest New Year’s Eve was even used for entertainment purposes, such as party in his/her town, with the largest crowd, the in literature. -

The Talent House: First-Look Images Revealed East London Dance and Ud’S Vibrant New Creative Hub in the Heart of Stratford’S Sugar House Island Opening This Autumn

THE TALENT HOUSE: FIRST-LOOK IMAGES REVEALED EAST LONDON DANCE AND UD’S VIBRANT NEW CREATIVE HUB IN THE HEART OF STRATFORD’S SUGAR HOUSE ISLAND OPENING THIS AUTUMN Thursday 25 March 2021: To mark the lease completion and start of our fit-out, East London Dance and UD are delighted to reveal first-look images of The Talent House, a vibrant new creative hub on Sugar House Island in Stratford that will bring the two organisations together under one roof. With high-performance professional facilities spanning across three floors housed in a historic warehouse with a modern extension, The Talent House is purpose-built to facilitate and encourage the passions and aspirations of dance and music artists, supporting young people and local communities on every step of their creative journey. Designed by Waugh Thistleton with internal design by award-winning architect Katy Marks, from Citizens Design Bureau, and located within a new development by Vastint UK, the building comprises two dance studios, five music production/recording studios, a live room and two vocal booths, a large flexible rehearsal/events space and a tech lab for education and training. The design brief also includes a shared area for building users and members, including a canteen and co-working space, and a central atrium functioning as the main reception of The Talent House and as a space for dance jams and informal gigs. This new permanent home will enable East London Dance and UD, long-standing champions of the next generation of artists, entrepreneurs and creative leaders, to support even more outstanding but under-represented talent - developing their skills, nurturing confidence and helping to build careers. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

With Alcohol

Faculty of Health Sciences National Drug Research Institute An ethnographic study of recreational drug use and identity management among a network of electronic dance music enthusiasts in Perth, Western Australia Rachael Renee Green This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University September 2012 i Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ………………………... ii Abstract This thesis explores the social contexts and cultural significance of amphetamine- type stimulant (ATS) and alcohol use among a social network of young adults in Perth, Western Australia. The study is positioned by the “normalisation thesis” (Parker et al . 1998), a body of scholarly work proposing that certain “sensible” forms of illicit drug use have become more culturally acceptable or normal among young people in the United Kingdom (UK) population since the 1990s. Academic discussion about cultural processes of normalisation is relevant in the Australian context, where the prevalence of illicit drug use among young adults is comparable to the UK. This thesis develops the work of Sharon Rødner Sznitman (Rødner, 2005, 2006; Rødner Sznitman, 2008), who argued that normalisation researchers have neglected the “micro-politics that drug users might be engaged in when trying to challenge the stigma attached to them” (Rødner Sznitman, 2008, pp.456-457). Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted among ‘scenesters’ – members of a social network that was based primarily on involvement in Perth’s electronic dance music (EDM) ‘scene’. -

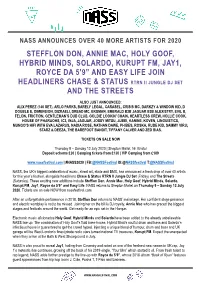

Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo

NASS ANNOUNCES OVER 40 MORE ARTISTS FOR 2020 STEFFLON DON, ANNIE MAC, HOLY GOOF, HYBRID MINDS, SOLARDO, KURUPT FM, JAY1, ROYCE DA 5’9” AND EASY LIFE JOIN HEADLINERS CHASE & STATUS RTRN II JUNGLE DJ SET AND THE STREETS ALSO JUST ANNOUNCED: ALIX PEREZ (140 SET), ARLO PARKS, BARELY LEGAL, CARASEL, CRISIS MC, DARKZY & WINDOW KID, D DOUBLE E, DIMENSION, DIZRAELI, DREAD MC, EKSMAN, EMERALD B2B JAGUAR B2B ALEXISTRY, EVIL B, FELON, FRICTION, GENTLEMAN’S DUB CLUB, GOLDIE LOOKIN’ CHAIN, HEARTLESS CREW, HOLLIE COOK, HOUSE OF PHARAOHS, IC3, INJA, JAGUAR, JOSSY MITSU, JUBEI, KANINE, KOVEN, LINGUISTICS, MUNGO’S HIFI WITH EVA LAZARUS, NADIA ROSE, NATHAN DAWE, PHIBES, ROSKA, RUDE KID, SAMMY VIRJI, STARZ & DEEZA, THE BAREFOOT BANDIT, TIFFANY CALVER AND ZED BIAS. TICKETS ON SALE NOW Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020 | Shepton Mallet, Nr. Bristol Deposit scheme £30 | Camping tickets from £130 | VIP Camping from £189 www.nassfestival.com | #NASS2020 | FB:@NASSFestival IG:@NASSfestival T:@NASSfestival NASS, the UK's biggest celebration of music, street art, skate and BMX, has announced a fresh drop of over 40 artists for this year’s festival, alongside headliners Chase & Status RTRN II Jungle DJ Set (Friday) and The Streets (Saturday). These exciting new additions include Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo, Kurupt FM, Jay1, Royce da 5’9” and Easy Life. NASS returns to Shepton Mallet on Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020. Tickets are on sale NOW from nassfestival.com After an unforgettable performance in 2018, Stefflon Don returns to NASS’ mainstage. Her confident stage presence and electric wordplay is not to be missed. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Lab on a Chip Systems for Biochemical Analysis, Biology and Synthesis

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Lab on a Chip Systems for Biochemical Analysis, Biology and Synthesis Towards Simple, Scalable Microfabrication Technologies Based on COC and LTCC Miguel Berenguel Alonso Tesi Doctoral Programa de Doctorat en Qu´ımica Directors: Mar Puyol and Juli´anAlonso Chamarro Departament de Qu´ımica Facultat de Ci`encies 2017 Mem`oriapresentada per aspirar al Grau de Doctor per Miguel Berenguel Alonso Vist i plau Mar Puyol Juli´anAlonso Chamarro Professora Agregada Catedr`atic Departament de Qu´ımica Departament de Qu´ımica Bellaterra, 6 de Juny de 2017 iii The present dissertation was carried out with the following financial support: CTQ2009-12128 Nuevas plataformas microflu´ıdicaspara la miniaturizaci´on de sistemas (bio)anal´ıticos integrados e intensificaci´onde procesos de producci´onde nanomateriales. Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovaci´on,co- funded by FEDER. 2009SGR0323 Convocat`oriade suport als Grups de Recerca de Catalunya. Departament d'Universitats, Recerca i Societat de la Informaci´o,Gen- eralitat de Catalunya. FI-DGR 2012 Pre-doctoral scholarship FI-DGR granted by the Ag`enciade Gesti´od'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Generalitat de Catalunya, and co-funded by the ESF. -

2010 Shorter University Lady Hawks Volleyball

2010 SHORTER UNIVERSITY LADY HAWKS VOLLEYBALL WE MEAN BUSINESS. TABLE OF CONTENTS / QUICK FACTS Introduction ................................................. 3-13 School Information Quick Facts .............................................. 3 Location .................................... Rome, Georgia The New U ............................................. 4-5 Founded ................................................ 1873 Winthrop-King Centre ................................ 6-7 Enrollment ............................................ 2,900 President, Dr. Harold E. Newman .................. 8-9 President .......................... Dr. Harold E. Newman Director of Athletics, Bill Peterson .............. 10-11 Director of Athletics .........................Bill Peterson We Mean Business .................................. 12-13 Nickname .......................................Lady Hawks Colors ..................................Royal Blue & White Season Preview ........................................... 14-19 Affiliation ...................................NAIA Division I 2010 Outlook ....................................... 14-15 Conference..............Southern States Athletic (East) 2010 Schedule .......................................... 16 2010 SSAC East Opponents ........................... 17 Home Court ........................Winthrop-King Centre 2010 Rosters ............................................ 18 Capacity ............................................... 2,500 2010 Media Roster ..................................... 19 Athletic -

Hip-Hop Is My Passport! Using Hip-Hop and Digital Literacies to Understand Global Citizenship Education

HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Teaching and Educational Policy – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton Hip-hop has exploded around the world among youth. It is not simply an American source of entertainment; it is a global cultural movement that provides a voice for youth worldwide who have not been able to express their “cultural world” through mainstream media. The emerging field of critical hip-hop pedagogy has produced little empirical research on how youth understand global citizenship. In this increasingly globalized world, this gap in the research is a serious lacuna. My research examines the intersection of hip-hop, global citizenship education and digital literacies in an effort to increase our understanding of how urban youth from two very different urban areas, (Detroit, Michigan, United States and Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) make sense of and construct identities as global citizens. This study is based on the view that engaging urban and marginalized youth with hip-hop and digital literacies is a way to help them develop the practices of critical global citizenship. Using principled assemblage of qualitative methods, I analyze interviews and classroom observations - as well as digital artifacts produced in workshops - to determine how youth define global citizenship, and how socially conscious, global hip-hop contributes to their definition Copyright by AKESHA MONIQUE HORTON 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful for the wisdom and diligence of my dissertation committee: Michigan State University Drs.