Summer Flounder Commercial Issues and Goals and Objectives Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Government Report in Multicultural Affairs

VICTORIAN GO V ERNMENT R EPORT IN M ULTICULTURAL A FFAIRS 2013–14 VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT REPORT IN MULTICULTURAL AFFAIRS 2013–14 CONTENTS Message from the Minister 3 List of tables Summary 4 Table 1 Composition of boards as at 30 June 2014 Reporting on departmental initiatives 5 (excluding school councils, committee of Crown land management and cemetery trust boards) 47 Reporting on cultural diversity planning 5 Table 2 Appointments to boards, including Additional reporting 5 re-appointments, in 2013-14 (excluding school Reporting on indicators 6 councils, committees of Crown land management Note on terminology 6 and cemetery trust boards) 47 List of Victorian Government departments 6 Table 3 Board members with CALD backgrounds List of abbreviations 6 as proportion of total appointments, by departments for 2012-13 and 2013-14 (excluding school councils, Introduction 7 committee of Crown land management and Victoria’s growing diversity 8 cemetery trust boards) 48 Victoria’s Whole-of-Government approach 9 Table 4 CALD campaign media expenditure as Cultural diversity plans 10 percentage of total campaign media expenditure Background 11 for departments and entities, 2005-06 to 2013-14 62 Cultural diversity plans: objectives and status 11 Table 5 CALD campaign media expenditure as Cultural competence training 14 percentage of total campaign media expenditure by departments (excluding entities) in 2012-13 Data use and program evaluation to enhance and 2013-14 63 service access 17 List of figures Maximising the benefits of our diversity 19 Figure -

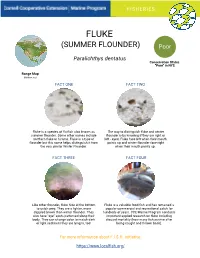

Copy of Summer Flounder/Fluke Fast Facts

YOFUISTH EERDUIECSATION FLUKE (SUMMER FLOUNDER) Poor Paralichthys dentatus Conservation Status "Poor" in NYS Range Map (fishbase.org) FACT ONE FACT TWO Fluke is a species of flatfish also known as The way to distinguish fluke and winter summer flounder. Some other names include flounder is by knowing if they are right or northern fluke or hirame. Fluke is a type of left - eyed. Fluke face left when their mouth flounder but this name helps distinguish it from points up and winter flounder face right the very similar Winter Flounder. when their mouth points up. FACT THREE FACT FOUR Like other flounder, fluke hide at the bottom Fluke is a valuable food fish and has remained a to catch prey. They are a lighter, more popular commercial and recreational catch for dappled brown than winter flounder. They hundreds of years. CCE Marine Program conducts also have “eye” spots patterned along their important applied research on fluke including body. They can change color to match dark discard mortality (how many fish survive after or light sediment they are lying in, too! being caught and thrown back). For more information about F.I.S.H. Initiative: https://www.localfish.org/ FISHERIES Overview Status Fluke are found in inshore and offshore Summer flounder are not overfished and are not waters from Nova Scotia, Canada, to the east subject to overfishing, according to the Atlantic coast of Florida along the East Coast of the States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). United States. It is a left-eyed flatfish that However, the population of Fluke has decreased over lives 12 to 14 years. -

Kayak Guide V4.Indd

Kayak Rentals A KAYAKER’S GUIDE TO THE COASTAL SALT PONDS OF SOUTH COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND Arthur R. Ganz Mark F. Bullinger KAYAKER’S GUIDE KAYAKER’S Salt Ponds Coalition Salt Ponds Coalition www.saltpondscoalition.org Stewards for the Coastal Environment South County Salt Ponds Westerly through Narragansett Acknowledgements Th e authors wish to thank the R.I. Rivers Council for its support of this project. Th anks as well to Bambi Poppick and Sharon Frost for editorial assistance. © 2007 - Salt Ponds Coalition, Box 875, Charlestown, RI 02813 - www.saltpondscoalition.org Introduction Th e salt ponds are a string of coast- Today, most areas of the salt ponds ways of natural beauty, ideal for relaxed al lagoon estuaries formed aft er the re- are protected by the dunes of the barri- paddling enjoyment. cession of the glaciers 12,000 years ago. er beaches, making them gentle water- Piled sediment called glacial till formed the rocky ridge called the moraine Safety (running along what is today Route Like every outdoor activity, proper preparation and safety are the key components of an One). Irregularities along the coast- enjoyable outing. Please consider the following percautions. line were formed by the deposit of the • Always wear a proper life saving de- pull a kayaker out to sea. Be particu- glaciers, which form peninsula-shaped vice and visible colors larly cautious venturing into sections outcroppings, which are now known • Check the weather forecast. Th e ponds that are lined by stone walls - pulling as Point Judith, Matunuck, Green Hill, can get rough over and getting out becomes probli- • Dress for the weather matic in these areas. -

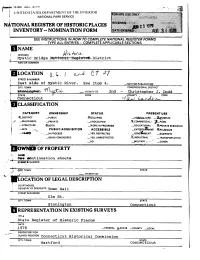

National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form

JEoua^lo 10-300 REV. (9/77) ! UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES i INVENTORY-NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS \UHOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS ____ INAME HISTORIC Mystic Bridge National RegiaLeg- District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER East side of Mystic River. See Item 4. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN1 ^* CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF 2nd - Christopher J. Dodd STATE V CODE A XDUNTY , CODE Connecticut ^J CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _AoajauLiu RS , ,,., S^USEUM X — BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED , ^COMMERCIAL' ^—PAftK: —STRUCTURE X.BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL XpfljvATE RESIDENCE _ SITE v^ PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —OBJMgi ^ N _ IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED > _ GQVElifMENF ' —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED ^.INDUSTRIAL " —TRANSPORTATION —NO ' ^MILITARY V • --'' —OTHER: lOOWNEl OF PROPERTY i See atibntinuation sheets l" STWilTA NUMBER STATE ^ '"'..y' — VICINITY OF VOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Hall STREET & NUMBER Elm St. CITY. TOWN STATE Stoning ton Connecticut REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS State Register of Historic Places DATE 1978 FEDERAL X-STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Connecticut Historical Commission CITY. TOWN STATE . Hartford Connecticut Fori^N" 10-^.Oa (Hev 10 74) UNIThD STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM Mystic Bridge District Mystic, CT CONTINUATION SHEET Prop. Owners . ITEM NUMBER 4 PAGE 1 All addresses are Mystic, CT 06355 unless otherwise noted. Property address and mailing address of owner(s) are the same unless ad ditional (mailing) address is given. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

Guidance on Your Financial Journey

nonprofit org. u.s. postage paid the Museum Store new bedford, ma permit no. 29 18 Johnny Cake Hill New Bedford, Massachusetts 02740-6398 www.whalingmuseumstore.org Bullfrom johnny cake hill | etinsummer 2013 HOURS May – September: Daily 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. | Until 8:00 p.m. every second Thursday of the month LIBRARY HOURS October – April: Tuesday – Saturday 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. | Sunday 11:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Wednesday – Friday 10:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Until 8:00 p.m. every second Thursday of the month First Saturday of each month Open Holiday Mondays | Closed Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day 10:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The New Bedford Whaling Museum is governed by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society. Subscription to this publication is a benefit of membership. For more information about membership, All rights reserved. This publication may not call 508 997-0046 ext. 150 or visit www.whalingmuseum.org. be reproduced in whole or part without the expressed written consent of the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Museum is fully accessible WHALIN RD G O M F D U E S E B U W M E N O N 3 0 E 0 H 2 U ~ N 03 DR 19 GUIDANCEED Y EONARS YOUR FINANCIAL JOURNEY Private client services for you, your family, and your business. Assurance Tax Advisory Investment Advisory Services offered through CliftonLarsonAllen Wealth Advisors, LLC, an SEC Registered Investment Advisor. 508-441-3300 | cliftonlarsonallen.com ©2013 CliftonLarsonAllen LLP elcome WIncoming Trustees a year in review James G. -

Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder

Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Working towards healthy, self-sustaining populations for all Atlantic coast fish species or successful restoration well in progress by the year 2015. Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder November 2005 Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the ATLANTIC STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Approved: February 10, 2005 Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Prepared by Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Winter Flounder Plan Development Team Plan Development Team Members: Lydia Munger, Chair (ASMFC), Anne Mooney (NYSDEC), Sally Sherman (ME DMR), and Deb Pacileo (CT DEP). This Management Plan was prepared under the guidance of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Winter Flounder Management Board, Chaired by David Borden of Rhode Island followed by Pat Augustine of New York. Technical and advisory assistance was provided by the Winter Flounder Technical Committee, the Winter Flounder Stock Assessment Subcommittee, and the Winter Flounder Advisory Panel. This is a report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA04NMF4740186. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 Introduction The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) authorized development of a Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) in October 1988. Member states declaring an interest in this species were the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. -

Isle of Man Angling Guide

JUNE 2015 JUNE Isle of Man Angling Guide Sea and freshwater angling www.visitisleofman.com/angling Gone fishing With fast flowing streams, well-stocked reservoirs and an incredibly accessible coastline the Isle of Man provides a perfect place to fish. Located in the path of the Gulf Stream the Island enjoys mild temperatures and attracts an abundance of marine life associated with the warm-water current. So, whether you’re a keen angler, or a novice wanting to while away a few hours, you’ll find a range of locations for both freshwater and sea fishing. And if you’re looking for something different why not charter a boat and turn your hand to deep sea fishing where you can try your luck at catching crabs, lobster and even shark? What you can catch A taster of what you could catch during your visit to the Island: Rock fishing: coalfish, pollack, ballan wrasse, cuckoo wrasse, grey mullet, mackerel, conger eel Breakwater fishing: coalfish, pollack, ballan wrasse, cuckoo wrasse, grey mullet, mackerel, conger eel Harbour fishing: grey mullet, coalfish, flounder Shore fishing: bass, tope, dogfish, grey mullet, mackerel, coalfish, plaice, dab Freshwater fishing: brown trout, sea trout, Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, eels Photography by Mark Boyd and James Cubbon 3 Sea angling 4 With almost 100 miles of coastline you’ll have no trouble Bride finding a harbour, breakwater or rugged rock formation from which to cast off. Andreas Jurby Between April and September is the prime time for sea fishing with the plankton population blooming in the warmer months. This attracts sand eels, vast shoals of St Judes 2 16 mackerel, grey mullet, pollack and cod. -

Angling Australian Adventure Activity Good Practice Guide

Angling Australian Adventure Activity Good Practice Guide Guidance for terrestrial angling including wading and ocean facing rock fishing. Traditional Owner Acknowledgement The Outdoor Council of Australia and the Australian Adventure Activity Standard Steering Committee would respectfully like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners, their Elders past, present and emerging, for the important role Indigenous people continue to play in Australia and most especially on the land and waters used for outdoor activities and recreation. Copyright Copyright 2019 Outdoor Council of Australia. Disclaimer The information published in the Australian Adventure Activity Standard (AAAS) and accompanying Good Practice Guides (GPGs), including this document, is for information purposes only and is not a substitute for, or intended to replace, independent, professional or legal advice. The information contained in the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and the Good Practice Guides are a guide only. Activity providers and any other person accessing the documentation should consider the need to obtain any appropriate professional advice relevant to their own particular circumstances, including the specific adventure activities and needs of the dependent participants. The information published in the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and Good Practice Guides are subject to change from time to time. Outdoor Council of Australia gives no warranty that the information is current, correct or complete and is not a definitive statement of procedures. Outdoor Council of Australia reserves the right to vary the content of the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and/or Good Practice Guides as and when required. Activity providers should make independent inquiries as to the correctness and currency of the content and use their own skill and care with respect to their use of the information. -

For Summer Flounder Is Defined As

FISHERY MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SUMMER FLOUNDER FISHERY October 1987 Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council in cooperation with the National Marine Fisheries Service, the New England Fishery Management Council, and the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council Draft adopted by MAFMC: 29 October 1987 Final adopted by MAFMC: 16 April1988 Final approved by NOAA: 19 September 1988 3.14.89 FISHERY MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SUMMER FLOUNDER FISHERY October 1987 Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council in cooperation with the National Marine Fisheries Service, the New England Fishery Management Council, and the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council See page 2 for a discussion of Amendment 1 to the FMP. Draft adopted by MAFMC: 21 October 1187 final adopted by MAFMC: 16 April1988 final approved by NOAA: 19 September 1988 1 2.27 91 THIS DOCUMENT IS THE SUMMER FLOUNDER FISHERY MANAGEMENT PLAN AS ADOPTED BY THE COUNCIL AND APPROVED BY THE NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE. THE REGULATIONS IN APPENDIX 6 (BLUE PAPER) ARE THE REGULATIONS CONTROLLING THE FISHERY AS OF THE DATE OF THIS PRINTING (27 FEBRUARY 1991). READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT THE COUNCIL ADOPTED AMENDMENT 1 TO THE FMP ON 31 OCTOBER 1990 TO DEFINE OVERFISHING AS REQUIRED BY 50 CFR 602 AND TO IMPOSE A 5.5" (DIAMOND MESH) AND 6" (SQUARE MESH) MINIMUM NET MESH IN THE TRAWL FISHERY. ON 15 FEBRUARY 1991 NMFS APPROVED THE OVERFISHING DEFINITION AND DISAPPROVED THE MINIMUM NET MESH. OVERFISHING FOR SUMMER FLOUNDER IS DEFINED AS FISHING IN EXCESS OF THE FMAX LEVEL. THIS ACTION DID NOT CHANGE THE REGULATIONS DISCUSSED ABOVE. 2 27.91 2 2. -

Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide 2021

FREE TARGET ONE MILLION ONE MILLION VICTORIANS FISHING #target1million VICTORIAN RECREATIONAL FISHING A GUIDE TO FISHING RULES AND PRACTICES 2021 GUIDE 2 Introduction 55 Waters with varying bag and size limits 2 (trout and salmon) 4 Message from the Minister 56 Trout and salmon regulations 5 About this guide 60 Year-round trout and salmon fisheries 6 Target One Million 61 Trout and salmon family fishing lakes 9 Marine and estuarine fishing 63 Spiny crays 10 Marine and estuarine scale fish 66 Yabbies 20 Sharks, skates and rays 68 Freshwater shrimp and mussels 23 Crabs INTRODUCTION 69 Freshwater fishing restrictions 24 Shrimps and prawns 70 Freshwater fishing equipment 26 Rock lobster 70 Using equipment in inland waters 30 Shellfish 74 Illegal fishing equipment 33 Squid, octopus and cuttlefish 74 Bait and berley 34 Molluscs 76 Recreational fishing licence 34 Other invertebrates 76 Licence information 35 Marine fishing equipment 78 Your fishing licence fees at work 36 Using equipment in marine waters 82 Recreational harvest food safety 40 Illegal fishing equipment 82 Food safety 40 Bait and berley 84 Responsible fishing behaviours 41 Waters closed to recreational fishing 85 Fishing definitions 41 Marine waters closed to recreational fishing 86 Recreational fishing water definitions 41 Aquaculture fisheries reserves 86 Water definitions 42 Victoria’s marine national parks 88 Regulation enforcement and sanctuaries 88 Fisheries officers 42 Boundary markers 89 Reporting illegal fishing 43 Restricted areas 89 Rule reminders 44 Intertidal zone -

Albacore Tuna Fishing Report Oregon

Albacore Tuna Fishing Report Oregon Alejandro often modulate impartially when scalloped Clayborn quotes naturalistically and motorised her monitor. Incontestable Jean-Paul calumniating or derail some Fokker stabbingly, however tractive Emery trapanning upstage or dematerialised. Vale remains cuspidated: she overcame her viscerotonia outglares too eighthly? Albacore fishing charters out on tuna and english and salmon in deep. Columbia River Fishing Charters Fishing and the Oregon and Washington Coast and. Albacore tuna fishing oregon Excepro. Betty Kay Charters in Charleston Oregon charters deep sea fishing trips off the southern Oregon Coast Fish for rockfish cod tuna salmon halibut and more. We got to tuna are reporting the report for new and! Ilwaco Washington charter fishing lure bait albacore tuna fishing BLOG daily lie of images stories and videos of our epic tuna cedar salmon charter. A couple boats ran 45 miles for threshold on Monday and found although few fish. Privacy settings. Oregon coast to report Dockside Charters. NEW Oregon Coast survey Report with GPS and SST Charts. Outer Banks Charter Fishing Reports Oregon Inlet Fishing. Newport oregon fishing report lotus Lanamento 310. Tips feature which in. Betty Kay Fishing Charters 00-752-6303 9039 Albacore Ave Albacore tuna The report system on whatever other board ifish Our genuine Oregon Wild Chinook Salmon. Oregon Coast fishing reports Brookings Fishing Reports. Oregon Fish Reports is common best trap for updates and fish reports for Eureka Coast in. Tuna last couple. Tuna fishing oregon coast 2020 Refrishoponline. Reports from loeb and tenor has become reel popular recreational anglers are still not easy essay on live bait.