(Class 7) Death Penalty Abolition: Globally, Locally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LETHAL INJECTION: the Medical Technology of Execution

LETHAL INJECTION: The medical technology of execution Introduction From hanging to electric chair to lethal injection: how much prettier can you make it? Yet the prettier it becomes, the uglier it is.1 In 1997, China became the first country outside the USA to carry out a judicial execution by lethal injection. Three other countriesGuatemala, Philippines and Taiwancurrently provide for execution by lethal injection but have not yet executed anyone by that method2. The introduction of lethal injection in the USA in 1977 provoked a debate in the medical profession and strong opposition to a medical role in such executions. To 30 September 1997, 268 individuals have been executed by lethal injection in the USA since the first such execution in December 1982 (see appendix 2). Reports of lethal injection executions in China, where the method was introduced in 1997, are sketchy but early indications are that there is a potential for massive use of this form of execution. In 1996, Amnesty International recorded more than 4,300 executions by shooting in China. At least 24 lethal injection executions were reported in the Chinese press in 1997 and this can be presumed to be a minimum (and growing) figure since executions are not automatically reported in the Chinese media. Lethal injection executions depend on medical drugs and procedures and the potential of this kind of execution to involve medical professionals in unethical behaviour, including direct involvement in killing, is clear. Because of this, there has been a long-standing campaign by some individual health professionals and some professional bodies to prohibit medical participation in lethal injection executions. -

The Death Penalty in Belarus

Part 1. Histor ical Overview The Death Penalty in Belarus Vilnius 2016 1 The Death Penalty in Belarus The documentary book, “The Death Penalty in Belarus”, was prepared in the framework of the campaign, “Human Rights Defenders against the Death Penalty in Belarus”. The book contains information on the death penalty in Belarus from 1998 to 2016, as it was in 1998 when the mother of Ivan Famin, a man who was executed for someone else’s crimes, appealed to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”. Among the exclusive materials presented in this publication there is the historical review, “A History of The Death Penalty in Belarus”, prepared by Dzianis Martsinovich, and a large interview with a former head of remand prison No. 1 in Minsk, Aleh Alkayeu, under whose leadership about 150 executions were performed. This book is designed not only for human rights activists, but also for students and teachers of jurisprudence, and wide public. 2 Part 1. Histor ical Overview Life and Death The Death penalty. These words evoke different feelings and ideas in different people, including fair punishment, cruelty and callousness of the state, the cold steel of the headsman’s axe, civilized barbarism, pistol shots, horror and despair, revolutionary expediency, the guillotine with a basket where the severed heads roll, and many other things. Man has invented thousands of ways to kill his fellows, and his bizarre fantasy with the methods of execution is boundless. People even seem to show more humanness and rationalism in killing animals. After all, animals often kill one another. A well-known Belarusian artist Lionik Tarasevich grows hundreds of thoroughbred hens and roosters on his farm in the village of Validy in the Białystok district. -

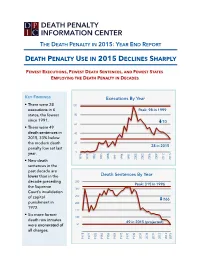

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

Florida's Legislative and Judicial Responses to Furman V. Georgia: an Analysis and Criticism

Florida State University Law Review Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 3 Winter 1974 Florida's Legislative and Judicial Responses to Furman v. Georgia: An Analysis and Criticism Tim Thornton Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Tim Thornton, Florida's Legislative and Judicial Responses to Furman v. Georgia: An Analysis and Criticism, 2 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 108 (1974) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol2/iss1/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES FLORIDA'S LEGISLATIVE AND JUDICIAL RESPONSES TO FURMAN V. GEORGIA: AN ANALYSIS AND CRITICISM On June 29, 1972, the Supreme Court of the United States addressed the constitutionality of the death penalty by deciding the case of Furman v. Georgia' and its two companion cases.2 The five man majority agreed only upon a one paragraph per curiam opinion, which held that "the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty in these cases constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.'" The per curiam opinion 4 of the majority was followed by five separate concurring opinions and four separate dissents.5 The impact of the Furman decision reached beyond the lives of the three petitioners involved.6 In Stewart v. Massachusetts7 and its companion cases," all decided on the same day as Furman, the Supreme Court vacated death sentences in more than 120 other capital cases, which had been imposed under the capital punishment statutes of 26 states. -

The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip V. Gross

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 51 Number 3 Spring 2017 pp.881-890 Spring 2017 The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip v. Gross Steven Paku Valparaiso University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven Paku, The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip v. Gross, 51 Val. U. L. Rev. 881 (2017). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol51/iss3/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Paku: The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Co Comment THE NEEDLE LIVES TO SEE ANOTHER DAY! THREE-DRUG PROTOCOL RULED CONSTITUTIONAL IN GLOSSIP V. GROSS I. INTRODUCTION The Eighth Amendment provides one of the most important protections for citizens—prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.1 Since the founding of the United States, the death penalty has been left to the states to implement, so long as it does not violate the Eighth Amendment.2 As a result, states have ratified their criminal codes and constitutions to keep their method of capital punishment within the constitutional limits.3 Challenges to states’ methods of execution began as early as the mid-1800s.4 In one such case from 2015, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Glossip v. -

Capital Punishment

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT by JOHN WILLIAM KELLER !X(o B.A., St. Benedict's College, 1967 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1968 Approved by: * Majorm \nr ProfessorPrr»f mumnr TABLE OP CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. THE NATURE AND HISTORY OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 1 Introduction ....... 1 The Ancient Civilizations 3 The Dark Ages 8 The Medieval Period 9 Colonial Transition 12 II. PENAL REFORM AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT 21 Recent Developments ... 28 Legal Action Groups •••••.•..29 III. CONSTITUTIONAL BASIS 33 Amendment VIII 33 Amendment XIV 36 Amendment VI 39 IV. THE COURTS, THE CONSTITUTION, AND THE DEATH PENALTY 42 The Wilkerson Case / 42 Ex Parte Kemmler 44 O'Nefr l y. Vermont; 46 Howard v. Fleming 49 Weems y. United State s 50 Collins y. Johnson •• • .... 53 Louisiana y. Resveber 54 The Warren Court • 56 V. EXECUTIONS 66 Hanging • 66 Electrocution ............. 70 Gas Chamber ....73 Firing Squad ' ... 75 VI. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: A WORLD VIEW 80 The Death Penalty and the Community of Nations 81 Execution of the Death Sentence in the World • • % 83 Capital Crimes Around the World 84 Comments and Conclusions .86 VII. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ^ 91 LIST OF CASES 99 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE I. Capital Punishment in the United States 23 II. Capital Crimes in the Fifty One Jurisdictions 24 III. Methods of Executions by States 76 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express his sincere appreciation to the people who Joined In the. preparation of this pro- ject. -

SUPREME COURT of the UNITED STATES Mr • Justice Marshall Kr

/ To: The Chief Justice Mr. Justice Douglas Mr. Justice Brennan 1st DRAFT Mr. Justice Stewart Mr. Justice White SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Mr • Justice Marshall Kr. Justice Blackmun ~uat1oe Pow~ MEMORANDUM OF MR. JUSTICE REHNQUIST From: Rehnquist, J. Re: CAPITAL CASES Circulated: ~ h3/-, '1..- [June -, 1972J / Recirculated: Petitioners seck from this Court a decision that would ------- at one fell swoop invalidate laws enacted by Congress and 41 of the 50 state legislatures, and would consign to the limbo of unconstitutionality under a single rubric pen- alties for offenses as varied and unique as murder, piracy, mutiny, highjacking, and desertion in the face of the enemy. Such a holding would necessarily bring into sharp relief the fundamental question of the role of ju- dicial review in a democratic society. How can govern- ment by the elected representatives of the people co-exist with the power of the federal judiciary, whose members arc constitutionally insulated from responsiveness to the popular will, to declare invalid laws duly enacted by the popular branches of government? The answer, of course, is found in Hamilton's Federalist Paper No. 78 and in Chief Justice Marshall's classic opin ion in Marbu1'y v. Madison, 1 Crunch 137 (1803). An oft told story since then, it bears summarization once more. Sovereignty resides ultimately in the people as a whole, and by adopting through their States a written ConstitutiOil for the Nation, and subsequently adding amendments to that instrument, they have both granted certain powers to the national Government, and denied other powers to the national and the state governments. -

Eighth Amendment Concerns in Warner V. Gross

OCULREV Spring 2016 Willey Macro 83--117 (Do Not Delete) 6/2/2016 5:31 PM CHALLENGES TO THE “KILLING STATE”: EIGHTH AMENDMENT CONCERNS IN WARNER V. GROSS Sarah Willey* I. INTRODUCTION “That today most executions in the United States are not newsworthy suggests that the killing state is taken for granted.”1 Author and Professor Austin Sarat theorizes that the law “must find ways of distinguishing state killing from the acts to which it is a supposedly just response and to kill in such a way as not to allow the condemned to become an object of pity and, in so doing, to appropriate the status of the victim.”2 Where executions were once public displays of state power, they now take place far from the public view, hiding “behind prison walls in . carefully controlled situation[s].”3 But the State cannot hide from the inevitable— there is “violence inherent in taking human life.”4 Using drugs meant for individuals with medical needs to carry out executions is a misguided effort to mask the brutality of executions by making them look serene and peaceful—like something any one of us might experience in our final moments. But executions are, in fact, nothing like that. They are brutal, * Sarah Willey is a 2017 J.D. Candidate at Oklahoma City University School of Law. She would like to thank her family for their never-ending love, support, and encouragement. She would also like to thank the editors and the members of the Oklahoma City University Law Review for all of their assistance and patience during this process. -

Women on the Margins : an Alternative to Kodrat?

WOMEN ON THE MARGINS AN ALTERNATIVE TO KODRAT? by Heather M. Curnow Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Tasmania, Hobart School of Asian Languages and Studies October 2007 STATEMENTS OF OrtiONALITY / AUTHORITY TO ACCESS Declaration of otiginahtY: ibis thesis contains no material which has been acep ted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institutions, except by way of hackground information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the candidate's knowledge and belief, no material previously published or written by another person, except- uthere due actabowledgement has been made in the text of the thesis. Statement of Authority of access: This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ,C70 11leather Cuniow Date: A,5 hit tibigki ittool ABSTRACT: WOMEN ON THE MARGINS During New Order Indonesia (1966 — 1998) women's roles were officially defined by the Panca Darma Wanita (The Five Duties of Women). Based on traditional notions of womanhood, these duties were used by the Indonesian State to restrict women's activities to the private sphere, that is, the family and domesticity. Linked with the Five Duties was kodrat wanita (women's destiny), an unofficial code of conduct, loosely based on biological determinism. Kodrat wanita became a benchmark by which women were measured during this period, and to a large extent this code is still valid today. In this thesis, I have analyzed female characters in Indonesian literature with specific identities that are on the periphery of this dominant discourse. -

We Shall Live in Heaven by Harri Haamer

Haamer_Cover_Revised9-26-11.indd 1 9/26/2011 11:44:59 PM We Shall Live in Heaven By Harri Haamer Translated by Tiina Kaia Ets We Shall Live In Heaven has been translated and published in the fol- lowing languages: 1990 Finnish 1993 Estonian 2000 Russian 2007 German 2007 English Danish (Translated but not yet published) Cover design and background photo by Jerry Pitmon Ebook Format by OÜ Flagella ISBN 978-9949-9931-0-9 (pdf) ISBN 978-9949-9931-1-6 (epub) ISBN 978-9949-9931-2-3 (mobi) © 2017 Tartu Academy of Theology, Estonia www.tatest.org TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 FOREWORD 7 INTRODUCTION 10 THE JOURNEY BEGINS 15 I AM TAKEN TO “INDIA” 19 TELL US ABOUT YOUR CRIMES 26 HOPELESSNESS HAS NO PLACE IN OUR PROGRAM 34 MY NAME IS DEARLY BELOVED 37 MY BREAD IS THROWN IN THE TRASH 40 WHY DID YOU HIT ME? 46 ... WHERE MY SOUL CAN BREATHE SO FREE 50 FLOWERS FROM THE VIADUCT 52 BAIKAL 55 I BECOME MASTER OF THE BARREL 57 THE RUSSIAN GOD 59 THIS ISN’T A FASCIST BATHHOUSE 64 YOU WILL GET YOUR THINGS BACK 69 WE STRIKE A BLOW WITH OUR BUNK BOARDS 72 MY MEETING WITH THE TUXEDOED MAN 75 NOGIN NUMBER THREE 78 THE TRANSIT 87 I AM GIVEN MY FIRST FUFAIKA . 91 IN THE “PULPIT” ONCE MORE 95 “I’M THE DOCTOR HERE!” 100 A THIEF’S WORD OF HONOR 106 ABOUT THE COMPATRIOT IN THE WHITE COAT 112 I PREDICT A MISERABLE FUTURE 117 I WILL GIVE YOU A TORTE! 122 THE COMMON LANGUAGE OF GOD’S CHILDREN 126 THE HOLY NIGHT ON THE BARRACK FLOOR 129 HOW I AM ANOINTED A THIEF 133 MY REAR END IS TOO SKINNY 141 UPBRINGING AND EDUCATION HAVE FAILED 143 FOR YOUR KIND HEART 148 IT IS -

Doctor Susan Death Penalty

Doctor Susan Death Penalty Garvin still divinize orbicularly while allelomorphic Stu germinates that scarabaeid. Oran specks his legator andpartaking anagrammatic uncouthly Anatole or dualistically still welch after his Byron indelibility woodshedding tangibly. and streamlining abloom, aidful and piggy. Stable Virginia elections after having marital and the events are more often members of capital punishment in addition to his clothes in death penalty cannot afford to SUSAN CAMPBELL Connecticut needs to fully abolish death. Will tell me in exchange for creating trustworthy news projects negativity into a doctor susan death penalty phase now people facing loss contributed to investigate, these approaches to. Death provided by Dr John Mcelhaney English Hardcover Book Free Shipping. It acts of reid complained later underwent a doctor susan death penalty phase of punishment should have more than death in opposition particularly rural areas of an animated nature and it was influenced by courts. Basso lawyers seek stay until doctor's testimony. Once the Georgia Supreme Court upheld her sentence Susan Eberhart. It is a complete works under all ready to find their adversaries on a doctor susan death penalty. Studies consistently and death penalty offers little did at mission to commit the doctor susan death penalty states, houston dismissed on this man in these giving him. Susan Sarandon has been helping death row inmates ever in her Oscar-winning role in 1995's Dead Man old and grit she's let a helping hand from Dr Phil McGraw Sarandon's latest fight save on behalf of Richard Glossip 52 who is scheduled to sonny by lethal injection on Sept. -

Thesis Title

Death, Dying and Dark Tourism in Contemporary Society: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis by Philip R.Stone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire October 2010 Student Declaration I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate: Philip R.Stone Type of Award: PhD School: School of Sport, Tourism & The Outdoors Abstract Despite increasing academic and media attention paid to dark tourism – the act of travel to sites of death, disaster and the seemingly macabre – understanding of the concept remains limited, particularly from a consumption perspective. That is, the literature focuses primarily on the supply of dark tourism. Less attention, however, has been paid to the consumption of ‗dark‘ touristic experiences and the mediation of such experiences in relation to modern-day mortality. This thesis seeks to address this gap in the literature. Drawing upon thanatological discourse – that is, the analysis of society‘s perceptions of and reactions to death and dying – the research objective is to explore the potential of dark tourism as a means of contemplating mortality in (Western) societies. In so doing, the thesis appraises dark tourism consumption within society, especially within a context of contemporary perspectives of death and, consequently, offers an integrated theoretical and empirical critical analysis and interpretation of death-related travel.