The Korean American Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YALE-NUS SYLLABUS for AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE THEATER of the 1960’S and 1970’S

YALE-NUS SYLLABUS FOR AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE THEATER OF THE 1960’s AND 1970’s YHU 3304, Spring semester, 2019 Mondays and Thursdays, 9am-10:30am Room Y-CR9 Professor Joan MacIntosh [email protected] Office hours by appointment only, Mondays, after class. Additionally, there will be a mid-semester conference with each student and an end-of-the-year conference with each student, to give and receive feedback. These will be scheduled within the semester time, and will not infringe on either the Spring Break or the end of the year Reading Period. COURSE OVERVIEW This seminar course will explore the American Avant-Garde Theatre of the 1960’s and 1970’s, and its enduring significance. It will include an examination of the political, social, economic, and aesthetic events that led to its beginnings, and will follow the journey of its passionate creativity and diversity of expression, as well as the political upheavals and the cultural revolution that were inextricably a part of it. Readings will include the work of Gertrude Stein, Allen Ginsberg, The Living Theatre, The Open Theater, The Performance Group, Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Company, Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Mabou Mines, and others. We will also read 1968, Environmental Theatre, Be Here Now, Towards a Poor Theatre, and selected historical overviews. We will explore each group’s vision, body of work, dynamics, and relation and significance to their world. In line with this, students will write about these theatre companies, and create their own live performances and work, based on the readings, possible films, and discussions. -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

Contemporary American Playwriting the Issue of Legacy

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PLAYWRITING The Issue of Legacy Jason Grote, Caridad Svich, and Anne Washburn in conversation with Ken Urban espite proclamations to the contrary, there is a surge of new writing in the American theatre. Not plays masquerading as films or TV shows, but seri- ous plays written by writers with a passionate commitment to the stage. DBut since this new generation of theatre artists is less centralized than previous ones, working in cities and towns across the U.S., it is hard to talk about a specific movement or scene. For those working in New York City, Off-Off Broadway no longer adequately describes the theatre that these playwrights create. Such writers do not want to be defined in relation to Broadway, for Broadway ceased to be a venue for adventurous new writing decades ago. This conversation is an attempt by four playwrights to define some of the identifying characteristics and concerns of this new writing. The starting point is the issue of legacy: How do the historical avant-garde, the Language Playwrights of the 1970s and 80s (Mac Wellman, Jeffrey Jones, Len Jenkin), and the classics influence contemporary playwriting? To gain a better sense of what is happening now, it proves beneficial to look back. The conversation featured Jason Grote, Caridad Svich, and Anne Washburn. Jason Grote is the recipient of the 2006 P73 Playwriting Fellowship and co-chair of the SoHo Rep Writer/Director Lab. He is writing The Wal-Mart Plays for the Working Theater in New York. Caridad Svich is a resident playwright at New Dramatists and editor of Trans-Global Readings: Crossing Theatrical Boundaries and Divine Fire: Eight Contemporary Plays Inspired by the Greeks. -

BRBL 2016-2017 Annual Report.Pdf

BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report Cover: Yale undergraduate ensemble Low Strung welcomed guests to a reception celebrating the Beinecke’s reopening. contributorS The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library acknowledges the following for their assistance in creating and compiling the content in this annual report. Articles written by, or adapted from, Phoenix Alexander, Matthew Beacom, Mike Cummings, Michael Morand, and Eve Neiger, with editorial guidance from Lesley Baier Statistics compiled by Matthew Beacom, Moira Fitzgerald, Sandra Stein, and the staff of Technical Services, Access Services, and Administration Photographs by the Beinecke Digital Studio, Tyler Flynn Dorholt, Carl Kaufman, Mariah Kreutter, Mara Lavitt, Lotta Studios, Michael Marsland, Michael Morand, and Alex Zhang Design by Rebecca Martz, Office of the University Printer Copyright ©2018 by Yale University facebook.com/beinecke @beineckelibrary twitter.com/BeineckeLibrary beinecke.library.yale.edu SubScribe to library newS messages.yale.edu/subscribe 3 BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report 4 From the Director 5 Beinecke Reopens Prepared for the Future Recent Acquisitions Highlighted Depth and Breadth of Beinecke Collections Destined to Be Known: African American Arts and Letters Celebrated on 75th Anniversary of James Weldon Johnson Collection Gather Out of Star-Dust Showcased Harlem Renaissance Creators Happiness Exhibited Gardens in the Archives, with Bird-Watching Nearby 10 344 Winchester Avenue and Technical Services Two Years into Technical -

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

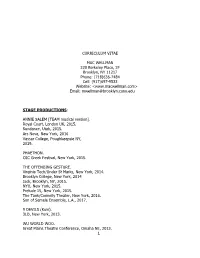

1 CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F

CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F Brooklyn, NY 11217 Phone: (718)636-7484 Cell: (917)697-9533 Website: <www.macwellman.com> Email: [email protected] STAGE PRODUCTIONS : ANNIE SALEM [TEAM musical version]. Royal Court, London UK, 2015. Sundance, Utah, 2015. Ars Nova, New York, 2016 Vassar College, Poughkeepsie NY, 2019. PHAETHON. CSC Greek Festival, New York, 2015. THE OFFENDING GESTURE. Virginia Tech/Under St Marks, New York, 2014. Brooklyn College, New York, 2014 Jack, Brooklyn, NY, 2015. NYU, New York, 2015. Prelude 15, New York, 2015. The Tank/Connelly Theater, New York, 2016. Son of Semele Ensemble, L.A., 2017. 9 DEVILS (Kuki). 3LD, New York, 2013. WU WORLD WOO. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2013. 1 Sleeping Weazel, Boston MA, 2013. HORROCKS (AND TOUTATIS TOO) Proposition series at the New Museum, New York, 2013. St Francis College, Brooklyn NY, 2013. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2013. Sleeping Weazel, Boston MA, 2013. 3 2's; or AFAR. Little Theater at Dixon Place, New York, 2011. Dixon Place, New York, 2011. Central Academy of Drama, Beijing China, 2014 MUAZZEZ. Tribeca Lighting/ Chocolate Factory, New York, 2011. Prelude 11, New York, 2011. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2012. Fisher Center, BAM, Brooklyn NY 2012. Fusebox Festival, Austin TX, 2013. PS 122 (COIL), Chocolate Factory, New York, 2014. DOCTOR RAVENELLO; OR 1965 UU. Theater Lang, New York, 2008. HotINK, NYU, New York, 2008. The Chocolate Factory, 2008. Proctor’s, Schenectady, 2008. NINE DAYS FALLING. Stuck Pigs/ Performing Lines, Melbourne Australia, 2007. BEFORE THE BEFORE AND BEFORE THAT (Twas the Night Before ...) Chelsea Art Museum and The Flea, New York, 2006. -

The Creative Application of Extended Techniques for Double Bass in Improvisation and Composition

The creative application of extended techniques for double bass in improvisation and composition Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Volume Number 1 of 2 Ashley John Long 2020 Contents List of musical examples iii List of tables and figures vi Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historical Precedents: Classical Virtuosi and the Viennese Bass 13 Chapter 2: Jazz Bass and the Development of Pizzicato i) Jazz 24 ii) Free improvisation 32 Chapter 3: Barry Guy i) Introduction 40 ii) Instrumental technique 45 iii) Musical choices 49 iv) Compositional technique 52 Chapter 4: Barry Guy: Bass Music i) Statements II – Introduction 58 ii) Statements II – Interpretation 60 iii) Statements II – A brief analysis 62 iv) Anna 81 v) Eos 96 Chapter 5: Bernard Rands: Memo I 105 i) Memo I/Statements II – Shared traits 110 ii) Shared techniques 112 iii) Shared notation of techniques 115 iv) Structure 116 v) Motivic similarities 118 vi) Wider concerns 122 i Chapter 6: Contextual Approaches to Performance and Composition within My Own Practice 130 Chapter 7: A Portfolio of Compositions: A Commentary 146 i) Ariel 147 ii) Courant 155 iii) Polynya 163 iv) Lento (i) 169 v) Lento (ii) 175 vi) Ontsindn 177 Conclusion 182 Bibliography 191 ii List of Examples Ex. 0.1 Polynya, Letter A, opening phrase 7 Ex. 1.1 Dragonetti, Twelve Waltzes No.1 (bb. 31–39) 19 Ex. 1.2 Bottesini, Concerto No.2 (bb. 1–8, 1st subject) 20 Ex.1.3 VerDi, Otello (Act 4 opening, double bass) 20 Ex. -

History of Towson University's MFA in Theatre Arts Program

Towson University: College of Fine Arts and Communication M.F.A. in Theatre Arts History of Towson University’s M.F.A. in Theatre Arts Program The MFA Program in Theatre Arts at Towson University started in 1994 under the leadership of Juanita Rockwell. In its 20‐year history, the program has engaged in a number of ambitious projects (originated by both students and faculty), presented over 60 theatre projects and performance pieces and received a number of outside accolades for these endeavors. Students and alumni have worked with a variety of professional artists and have also gone on to create theatre companies of their own. They have also taught at a number of colleges and universities, and have embarked on successful professional careers at institutions around the country. Tours MFA productions have toured to international festivals in Bulgaria, Slovakia, Egypt, Poland and Hungary. National tours of shows have included trips to Boston, New York City, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago, and Austin, Texas. In the summer of 2009, a group of MFA students did a Study Abroad Program to Wroclaw, Poland. There they attended the Grotowski Institute’s festival, “The World as a Place of Truth,” a celebration of the life and work of the famous Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski. The students also participated in a five‐day, six‐hours‐a‐day workshop with Teatr ZAR, the in‐house theatre company at the Grotowski Institute. In the summer of 2011, the program presented a showcase at the ToRoNaDa Space in New York City. The two‐week showcase, entitled Modicums, includes The Natasha Plays; Return to Sender by Shannon McPhee; The Title Sounded Better in French by Lola B. -

The-Vandal.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMPSON artistic director CAROL OSTROW producing director BETH DEMBROW managing director presents the world premiere of THE VANDAL written by HAMISH LINKLATER directed by JIM SIMPSON DAVID M. BARBER set design BRIAN ALDOUS lighting design CLAUDIA BROWN costume design BRANDON WOLCOTT sound design and original music MICHELLE KELLEHER stage manager EDWARD HERMAN assistant stage manager CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) Man...........................................................................................................................Zach Grenier Woman...............................................................................................................Deirdre O’Connell Boy...........................................................................................................................Noah Robbins CREATIVE TEAM Playwright...........................................................................................................Hamish Linklater Director.......................................................................................................................Jim Simpson Set Design..............................................................................................................David M. Barber Lighting Design.........................................................................................................Brian Aldous Costume Design......................................................................................................Claudia Brown Sound Design and Original -

Korean Dance and Pansori in D.C.: Interactions with Others, the Body, and Collective Memory at a Korean Performing Arts Studio

ABSTRACT Title of Document: KOREAN DANCE AND PANSORI IN D.C.: INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS, THE BODY, AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY AT A KOREAN PERFORMING ARTS STUDIO Lauren Rebecca Ash-Morgan, M.A., 2009 Directed By: Professor Robert C. Provine School of Music This thesis is the result of seventeen months’ field work as a dance and pansori student at the Washington Korean Dance Company studio. It examines the studio experience, focusing on three levels of interaction. First, I describe participants’ interactions with each other, which create a strong studio community and a women’s “Korean space” at the intersection of culturally hybrid lives. Second, I examine interactions with the physical challenges presented by these arts and explain the satisfaction that these challenges can generate using Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of “optimal experience” or “flow.” Third, I examine interactions with discourse on the meanings and histories of these arts. I suggest that participants can find deeper significance in performing these arts as a result of this discourse, forming intellectual and emotional bonds to imagined people of the past and present. Finally, I explain how all these levels of interaction can foster in the participant an increasingly rich and complex identity. KOREAN DANCE AND PANSORI IN D.C.: INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS, THE BODY, AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY AT A KOREAN PERFORMING ARTS STUDIO By Lauren Rebecca Ash-Morgan Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Dr. Robert C. Provine, Chair Dr. -

What's a Sijo?

What’s a Sijo? Poet Hwang Jin-I, 1506–1560, (there’s a K-drama about her!) often wrote sijo half in aristocratic Chinese, and half in Korean Sijo (pronounced she-joe) is a traditional Korean form of hanja used by women even though it was suppressed by the poetry. The earliest known one was written in the 14th scholar officials. Take this one, for example, where the first half century. Sijo are three lines long, each line 14–16 syllables. of each line is in Chinese, the second half in Korean: One type of sijo, called sijo chang, is sung so slowly, it has been called the “slowest song in the world.” Can you sense where the languages change? Sijo began as a sly political weapon. They were written at Jade Green Stream, don’t boast so proud first in classical Chinese by Yangban, the male aristocrats of the Korean ruling class, who were typically military officials of your easy passing through these blue hills. and civil servants. These writers disguised the political Once you have reached the broad sea, points they wanted to make by using nature poetry. By to return again will be hard. the 18th century, times had changed, sijo were written by While the Bright Moon fills these empty hills, everyone, and in Korean. why not pause? Then go on, if you will. —Hwang Jin-i, translation by David McCann Make your own Sijo! Use the word bank to fill in the blanks. old tiger forest hide listen annoy fly river magpie teeth stalk regal green wince stones be legs wing on parent dance powerful gull deer drink snow play crane bear water teach leaves baby ugly clouds hungry palace fight grow eat maple stripes in rain field love tall hare run of gawk So, the ___________ growled, you’ve come to ___________: animal or person verb Seok Mo Ro-in the ________ emperor __________ , locked in his __________.