Contemporary American Playwriting the Issue of Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F

CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F Brooklyn, NY 11217 Phone: (718)636-7484 Cell: (917)697-9533 Website: <www.macwellman.com> Email: [email protected] STAGE PRODUCTIONS : ANNIE SALEM [TEAM musical version]. Royal Court, London UK, 2015. Sundance, Utah, 2015. Ars Nova, New York, 2016 Vassar College, Poughkeepsie NY, 2019. PHAETHON. CSC Greek Festival, New York, 2015. THE OFFENDING GESTURE. Virginia Tech/Under St Marks, New York, 2014. Brooklyn College, New York, 2014 Jack, Brooklyn, NY, 2015. NYU, New York, 2015. Prelude 15, New York, 2015. The Tank/Connelly Theater, New York, 2016. Son of Semele Ensemble, L.A., 2017. 9 DEVILS (Kuki). 3LD, New York, 2013. WU WORLD WOO. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2013. 1 Sleeping Weazel, Boston MA, 2013. HORROCKS (AND TOUTATIS TOO) Proposition series at the New Museum, New York, 2013. St Francis College, Brooklyn NY, 2013. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2013. Sleeping Weazel, Boston MA, 2013. 3 2's; or AFAR. Little Theater at Dixon Place, New York, 2011. Dixon Place, New York, 2011. Central Academy of Drama, Beijing China, 2014 MUAZZEZ. Tribeca Lighting/ Chocolate Factory, New York, 2011. Prelude 11, New York, 2011. Great Plains Theatre Conference, Omaha NE, 2012. Fisher Center, BAM, Brooklyn NY 2012. Fusebox Festival, Austin TX, 2013. PS 122 (COIL), Chocolate Factory, New York, 2014. DOCTOR RAVENELLO; OR 1965 UU. Theater Lang, New York, 2008. HotINK, NYU, New York, 2008. The Chocolate Factory, 2008. Proctor’s, Schenectady, 2008. NINE DAYS FALLING. Stuck Pigs/ Performing Lines, Melbourne Australia, 2007. BEFORE THE BEFORE AND BEFORE THAT (Twas the Night Before ...) Chelsea Art Museum and The Flea, New York, 2006. -

YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30Pm

#BAMNextWave #YouUsWeAll Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30pm Running time: one hour & 20 minutes, no intermission Music by Shara Worden Text, direction, and design by Andrew Ondrejcak B.O.X. (Baroque Orchestration X) Season Sponsor: Leadership support for opera at BAM provided by Aashish & Dinyar Devitre Endowment funding has been provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Opera and Music-Theater Major support for opera at BAM provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust YOU US WE ALL CAST HOPE Shara Worden VIRTUE Helga Davis LOVE Martin Gerke DEATH Bernhard Landauer TIME Carlos Soto B.O.X. ENSEMBLE A Continuo/Rythm Section Theorbo, artistic direction Pieter Theuns Harpsichord, organ Anthony Romaniuk Baroque harp Jutta Troch Drums, percussion Mattijs Vanderleen An Alta Capella of Winds Cornett, flutes Lambert Colson Cornett, trumpet Jon Birdsong Sackbut (baroque trombone) Liza Malamut A Consort of Viols Treble viol, bass viol Liam Byrne Bass viol Pieter Vandeveire Violone Christine Sticher PRODUCTION CREDITS Stage, light, costume, projection design Andrew Ondrejcak Choreographer Seth Stewart Williams Production dramaturg Anne Seiwerath Executive producer/tour management ArKtype/Thomas O. Kriegsmann Production manager/lighting director Davison Scandrett Production stage manager Valerie Oliveiro Assistant stage manager Nina Segal Video design consultant Andrew Bauer Video supervisor Tei Blow Co-lighting design Lutz Deppe Co-costume design Zane Philstrom Assistant director Cecile Tonizzo Sound design David Schnirman/Hear No Evil Wig design Rick Gradone Make-up design Marco Campos Assistant, costumes and wardrobe Baille Younkman Assistant, costumes Julie Michaels Production assistant Veerle Van Rossom YOU US WE ALL is commissioned by B.O.X. -

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

On the Downtown Scene

ON MAC THE SCENEDOWNTOWN WELLMAN 36 | The Dramatist pp36-41 Feature D.indd 36 3/31/12 5:45 PM Annie Baker: What were some of your favorite Mac Wellman is a shows this past season and why? teacher who changed Mac Wellman: Hmm. Definitely Erin Court- ney’s A Map Of Virtue and, surprisingly, our Brook- my life. He is one of lyn College/Classic Stage Company Weasel Festival of last August (four plays based on the the smartest and most mystery novels of Norbert Davis – the favorite mystery writer of Ludwig Wittgenstein) by Caitlin generous writers I have Brubaker, Alexandra Collier, Ariel Stess, and Sara Farrington with brilliant direction by Brubaker & ever known; maybe Sarah Rasmussen. Also, I very much liked Thomas Bradshaw’s Burning and Young Jean Lee’s Untitled one of the smartest and Feminist Show. And, of course, Sybil Kempson’s splendid Secret Death Of Puppets, Julia Jarcho’s generous ever to exist. Dreamless Land, and Away Uniform by Tina Satter. AB: What do these (apparently very different) Since he is an avid theatre writers share? theatregoer and a lover MW: An attitude towards story-telling that is very different from the norm in our theatre in of new work, I asked These States. Often their plays operate like a game of three-dimensional chess: characters him for his take on who are firmly located in one apparent world suddenly find themselves in a situation that is the 2011/12 season in drastically elsewhere (A Map of Virtue for in- stance); or we as an audience find ourselves so downtown NYC theatre. -

Chapter 1 Introduction: Improper Naming

Notes Chapter 1 Introduction: Improper Naming 1. The allusion of Ru, Vi, and Flo to the flowers adorning Ophelia (described in Hamlet Act IV Scenes v and vii) is probably more than a coincidence, as an early version of the play held in the Beckett Collection at Reading University Library suggests that Beckett originally called the characters Viola, Rose, and Poppy. 2. In Kane’s slightly earlier plays – Blasted (showcased in 1993), Phaedra’s Love (produced in 1996), and Cleansed (produced in April 1998) – they are given names. The characters in Crave (produced in August 1998) are referred to only by letters (C, M, B, A); and in the posthumously produced 4.48 Psychosis (2000), there are no character names. The ‘I’ that speaks throughout 4.48 Psy- chosis is singular but split: three performers speak the ‘I’, arguably reflecting a triad voiced by the ‘I’ itself: ‘Victim/ Perpetrator/ Bystander’ (Kane, 2001, p. 231). 3. These insights derive in part from a response from Vogel by email to my question about the name ‘Anna’. 4. Prefiguring Lehmann, Bonnie Marranca states, in her introduction to the three-text collection The Theatre of Images (a work each by Robert Wilson, Lee Breuer, and Richard Foreman), that ‘value came to be increasingly placed on performance with the result that the new theatre never became a literary theatre, but one dominated by images – visual and aural. This is the single most important feature of contemporary American theatre’ (Marranca, p. ix). 5. Mac Wellman, ‘Writers’ Bloc’, Village Voice 18 May 2004, retrieved: www.villagevoice.com (para 6 of 9). -

Emerson's Moving Assignments

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Committing to the Waves: Emerson's Moving Assignments Karinne Keithley Syers Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/295 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COMMITTING TO THE WAVES: EMERSON'S MOVING ASSIGNMENTS by KARINNE KEITHLEY SYERS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 KARINNE KEITHLEY SYERS All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy. _____Professor Joan Richardson________ ___________________ __________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _____Professor Mario DiGangi_________ ___________________ __________________________________ Date Executive Officer _____Professor Ammiel Alcalay________ _____Professor Wayne Koestenbaum____ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract COMMITTING TO THE WAVES: EMERSON'S MOVING ASSIGNMENTS by Karinne Keithley Syers Adviser: Joan Richardson Committing to the Waves: Emerson's Moving Assignments reads Ralph Waldo Emerson as a writer of assignments for living and working whose senses can be taken up across a wide array of creative and exploratory fields. Shifting between an interdisciplinary array of contexts ranging from philosophy and poetics to dance, performance, and somatic movement experiments, I join the practical sense of creative inquiry embodied in these fields to the abstract images of Emerson's assignments. -

Mac Wellman and the Language Poets: Chaos Writing and the General Economy of Language

Spring 2010 69 Mac Wellman and the Language Poets: Chaos Writing and the General Economy of Language Keith Appler Shake the flour can, get the particles. You lift the rod one inch too far, and the core’s crazy, you’re plastered on account of the ceiling. —Mac Wellman’s Cellophane By the time Marjorie Perloff would write the foreword to the 2001 Cellophane: Plays by Mac Wellman, she would note that, in addition to Bertolt Brecht, Samuel Beckett, Sam Shepard, and Harold Pinter, Mac Wellman also “recalls . the language poets–Bruce Andrews, Charles Bernstein, Steve McCaffery–who are his contemporaries.”1 Wellman, a prolific experimental playwright, has corresponded with Bernstein at least since 1977,2 and among Wellman’s extensive bicoastal associates is the Language poet Douglas Messerli, founder of Sun and Moon Press of Los Angeles. Wellman, described as a “language” writer by New York Times reviewer Mel Gussow in 1990,3 is identified as aLanguage poet in 2008 by Helen Shaw in her foreword to Wellman’s third major play collection. Shaw writes that Wellman “has been the deconstructionists’ mountaintop; he has read the very choppy tablets given down by the Black Mountain gang and the Language Poets (he is one). But he also returns to us [in the theatre] with their message.”4 Shaw’s identification of Wellman as a Language poet in no way diminishes his importance in the theatre, although his first plays were radio plays adapted from his poetry, and his dramatic works, always off-beat, suggest his “poetical” preoccupation with producing unconventional and emphatically non-didactic effects through linguistic and theatrical means. -

CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F

CURRICULUM VITAE MAC WELLMAN 220 Berkeley Place, 2F Brooklyn, NY 11217 Phone: (718)636-7484 Cell: (917)697-9533 Website: <www.macwellman.com> Email: [email protected] STAGE PRODUCTIONS : 3 2's; or AFAR. Dixon Place, New York, 2011. MUAZZEZ. Tribeca Lighting/ Chocolate Factory, New York, 2011/12. DOCTOR RAVENELLO; OR 1965 UU. Theater Lang, New York, 2008. HotINK, NYU, New York, 2008. The Chocolate Factory, 2008. Proctor’s, Schenectady, 2008. NINE DAYS FALLING. Stuck Pigs/ Performing Lines, Melbourne Australia, 2007. BEFORE THE BEFORE AND BEFORE THAT (Twas the Night Before ...) Chelsea Art Museum and The Flea, New York, 2006. Apollinaire Theater Company, Chelsea MA, 2008. 2 SEPTEMBER. Trinity Rep, Providence RI, 2000. Bay Area Playwrights’ Festival, San Francisco CA, 2002 Undermain Theater, Dallas TX, 2004. The Flea theater, New York, 2006. BRING A WEASEL AND A PINT OF YOUR OWN BLOOD (OR: PSYCHOLOGY). Great Plains Theater Conference, Omaha NE, 2006. Theater Outlet, Allentown PA, 2006. Stanford University, Palo Alto CA, 2007. Café Mao, Beijing China, 2009. LEFT GLOVE. Great Plains Theater Conference, Omaha NE, 2006. Five Myles, New York, 2007. THE INVENTION OF TRAGEDY. Write/ Act, NYU, New York, 2005. Classic Stage Company, New York, 2005. Write/Act, NYU, New York, 2007. Classic Stage Company, New York, 2007. Classic Stage Company, New York, 2009. THE DIFFICULTY OF CROSSING A FIELD. Baylor University, Waco TX, 1998. A.C.T., San Francisco CA, 1999. A.C.T./Theater Artaud, San Francisco CA, 2002. Ridge Theater/ Montclair State University, NJ 2006. University of Texas, Austin TX, 2010. Ridge Theater/Virginia Tech, Blackwater VA, 2011. -

Young Jean Lee's Theater Company

wexner center for the arts THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESENTS world premiere Wexner Center Artist Residency Award Project Young Jean Lee’s Theater Company STRAIGHT WHITE MEN THU–SAT, APR 10–12 | 8 pm SUN, APR 13 | 2 pm Performance Space 2013–14 PERFORMING ARTS SEASON world premiere Thank you for Wexner Center Artist Residency Award Project Young Jean Lee’s Theater Company joining us at tonight’s STRAIGHT WHITE MEN THU–SAT, APR 10–12 | 8 pm performance. SUN, APR 13 | 2 pm Performance Space STRAIGHT WHITE MEN is a production by a nonprofit real estate organization Special thanks to all Wexner Center Young Jean Lee’s Theater Company. It dedicated to expanding the supply of long- was commissioned by the Wexner Center term, affordable rehearsal and studio space members and sponsors. Your support makes for the Arts at The Ohio State University; for NYC artists. Center Theatre Group, Los Angeles; This presentation of Young Jean Lee’s this event possible. steirischer herbst festival, Graz; Les Theater Company’s STRAIGHT WHITE MEN spectacles vivants—Centre Pompidou, is made possible with funding by the Paris; Festival d’Automne à Paris; and The The Wexner Center for the Arts is your one-stop New England Foundation for the Arts’ Public Theater, New York. National Theater Project, with lead source for everything in the contemporary arts. Funding support for the creative funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Come back and check out our groundbreaking development of STRAIGHT WHITE Foundation. Additional support is provided MEN was provided by the Doris Duke by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

1976 – Vol 1 #1 Jan 22, 1978: Letter from BM to Lee Breuer & Ruth Re

1976 – Vol 1 #1 Jan 22, 1978: Letter from BM to Lee Breuer & Ruth re: Shaggy Dog Animation Booklet Mabou Mines’ – “The Red Horse Animation” Photograph “Deafman Glance” Small flier Mabou Mines “New work and old work” at Paula Cooper Gallery Photo Mabou Mines “Shaggy Dog Animation” by Johan Elbers Photo Mabou Mines “Red Horse” photo by Roberta Neiman Essay How We Work: Mabou Mines by Lee Breur 1976 - Vol 1 #2 Flier The Wooster Group “Lava.” Flier Hotel for Criminals Flier Ontological-Hysteric Theatre “Pandering to the Masses: Misrepresentation.” Flier Ontological-Hysteric Theatre “The Cure” Flier Ontological-Hysteric Theatre “Rhoda In Potatoland” Flier Richard Foreman’s “Zomboid!” Flier Ontological-Hysteric Theatre “Here it comes! Historic collaboration!” Photo “Vertical Mobility” credit: Babette Mangolte Photo “pandering to the masses” credit: Babette Mangolte “How to write a play” Foreman (1st page) 1977 Vol II #2 Sontag Interview Photo Susan Sontag credit: Jill Krementz Vol II #3 Erwin Piscator + pictures in article. Vol III #2 Wooster Group, rumstick road p80-81 Photo Nayatt School (1978) cred Clem Fiori Photo Rumstick road (1977) Credit Mary Gearheart. Spalding Gray on the phone with his mother’s psychiatrist; with Bruce Porter in the sound booth and Libby Howes in the background. Photo “the Emperor Jones” directed by Elizabeth LeCompte (left to right) Willem Dafoe, Dave Shelley in shadow) Brussels, April 1996 Photo The Wooster Group “Brace Up!” Dir. Elizabeth LeCompte Cred. Paula Court Photo the Wooster Group “LSD… Just the High points” Dir. Elizabeth LeCompte cred. Nancy Campbell 10/11 (display copy) 1979 *1957-58 Cage class at NS P23 The New Humanism P.70 Art in Culture Photatron p.84 (the highlights) + picture of J. -

The Korean American Context

Exploding Stereotypes Inside and Out: The Theatre of Young Jean Lee and Issues of Gender and Racial Identity Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Seunghyun Hwang, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Chan Park Copyright by Seunghyun Hwang 2010 Abstract Young Jean Lee is a playwright and director who has worked in New York City since 2002. She founded the Young Jean Lee's Theatre Company in 2003 where she produced a number of her own plays. She can be classified as a "1.5 generation" Asian American playwright who has added her particular voice about diasporic Asian woman’s issues to American theatre. Her creative and artistic interests were not limited to academic reading and writing, but expanded to live theatre and performance. Her works thematically involve the daily issues and interaction among contemporary American people. In her theatrical works, Young Jean Lee challenges the audience to rethink the nature of race or gender stereotypes in the USA through her trajectory of reconsidering these stereotypes. This thesis focuses on two of her most recent and controversial works, Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven (2006) and The Shipment (2008). Chapter 1 provides a brief overview of Asian American theatre history and specifically situates Lee’s work within a context of Korean American playwrights since 1990s where they appeared for the first time in any significant number. The next two chapters analyze Lee's multiple narratives of race, culture, and diaspora, and her attempt to deconstruct and explode ever present and recycled stereotypes of Asian Americans and African Americans. -

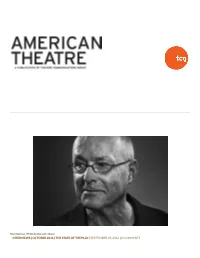

An Outlier Tracing His Own Orbit

You’re accessing a premium article on AmericanTheatre.org. You have 4 premium articles remaining. Please SUBSCRIBE or LOG IN to access unlimited premium articles. Mac Wellman. (Photo by Bronwen Sharp) INTERVIEWS | OCTOBER 2016 | THE STATE OF THE PLAY | SEPTEMBER 20, 2016 | 0 COMMENTS Mac Wellman: An Outlier Tracing His Own Orbit Mac Wellman: An Outlier Tracing His Own Orbit How this dedicated follower of no fashion and avatar of alternatives to the well-made play keeps it weird. BY ELIZA BENT Soon after I nished my playwriting MFA at Brooklyn College, a play of mine had a production that caused me more woe than delight. Was this kind of disappointment what my new career would entail? Why had I just spent years on an MFA? In the wake of the show’s closing, I found myself turning over these questions in my mind at the Great Plains Theatre Conference, where my former Brooklyn College teacher Mac Wellman was giving workshops and responding to plays. One day as we walked from a particularly tasty supper toward an evening performance, I opened up to Wellman about my private doubts. I gave a short speech that concluded with me stammering: “I just don’t know if I want to be a playwright anymore.” It was twilight, and Wellman was dressed in a black Japanese silk jacket with a lime green Kokopelli pin and a dark denim sherman’s hat. We were walking slowly—ambling, really. As I began to formulate further remarks, I simultaneously anticipated Wellman interrupting me with a rallying cry to carry on and buck up—with the pep talk I was subconsciously shing for.