AMA Journal of Ethics® November 2016, Volume 18, Number 11: 1067-1069

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flourishing of Transgender Studies

BOOK REVIEW The Flourishing of Transgender Studies REGINA KUNZEL Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies Edited by A. Finn Enke Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. 260 pp. ‘‘Transgender France’’ Edited by Todd W. Reeser Special issue, L’Espirit Createur 53, no. 1 (2013). 172 pp. ‘‘Race and Transgender’’ Edited by Matt Richardson and Leisa Meyer Special issue, Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011). 147 pp. The Transgender Studies Reader 2 Edited by Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura New York: Routledge, 2013. 694 pp. For the past decade or so, ‘‘emergent’’ has often appeared alongside ‘‘transgender studies’’ to describe a growing scholarly field. As of 2014, transgender studies can boast several conferences, a number of edited collections and thematic journal issues, courses in some college curricula, and—with this inaugural issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly—an academic journal with a premier university press. But while the scholarly trope of emergence conjures the cutting edge, it can also be an infantilizing temporality that communicates (and con- tributes to) perpetual marginalization. An emergent field is always on the verge of becoming, but it may never arrive. The recent publication of several new edited collections and special issues of journals dedicated to transgender studies makes manifest the arrival of a vibrant, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly * Volume 1, Numbers 1–2 * May 2014 285 DOI 10.1215/23289252-2399461 ª 2014 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/tsq/article-pdf/1/1-2/285/485795/285.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 286 TSQ * Transgender Studies Quarterly diverse, and flourishing interdisciplinary field. -

Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color Maureen Grace White University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Maureen Grace, "Resiliency Factors Among Transgender People of Color" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/182 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Psychology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT RESILIENCY FACTORS AMONG TRANSGENDER PEOPLE OF COLOR by Maureen G. White The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. Shannon Chavez-Korell Much of the research on transgender individuals has been geared towards identifying risk factors including suicide, HIV, and poverty. Little to no research has been conducted on resiliency factors within the transgender community. The few research studies that have focused on transgender individuals have made little or no reference to transgender people of color. This study utilized the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach to examine resiliency factors among eleven transgender people of color. -

Transgender Health Care Exclusions from CWRU’S Health Care Plans (2013)

Health Insurance Coverage for Transgender Related Healthcare: Introduction, Impact and Recommendations for CWRU Prepared by: Liz Roccoforte, Director, CWRU LGBT Center Definitions: Transgender: An umbrella term that refers to a broad range of gender identities and gender expressions. Basically, the term transgender refers to many identities and expressions that fall outside the “traditional” norms of gender. This is not a diagnostic term, and does not imply a medical or psychological condition. (adapted from http://transhealth.ucsf.edu) Transsexual : Transsexual is one of the gender identities that falls underneath the broader category of “transgender.” This term most often applies to individuals who seek hormonal (and often, but not always) surgical treatment to modify their bodies so they may live full time as members of the sex category opposite to their birth-assigned sex. (adapted from http://transhealth.ucsf.edu ) Introduction: “Transgender Related Health Care” refers to medical benefits relating to transgender individuals. Generally, this care refers to the coverage of procedures, surgeries and hormones associated with medical gender transition. Often, individuals seeking this kind of healthcare identify as transsexual. However, not all people seeking this care identify specifically as transsexual, but still meet the criteria for transition related care, therefore the broader term “transgender” is often used instead of “transsexual.” This health care coverage also refers to the coverage of healthcare needs that are not directly related to medical gender transition, but impacted by it. Currently, all CWRU employee health care plans explicitly exclude transgender related health care as a covered benefit. • Specifically, current employees seeking coverage for medical procedures, visits and pharmaceuticals, required for medical gender transition, are denied coverage by insurance. -

Opening the Door Transgender People National Center for Transgender Equality

opening the door the opening The National Center for Transgender Equality is a national social justice people transgender of inclusion the to organization devoted to ending discrimination and violence against transgender people through education and advocacy on national issues of importance to transgender people. www.nctequality.org opening the door NATIO to the inclusion of N transgender people AL GAY AL A GAY NATIO N N D The National Gay and Lesbian AL THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, L Task Force Policy Institute ESBIA C BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS is a think tank dedicated to E N FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE research, policy analysis and TER N strategy development to advance T ASK FORCE F greater understanding and OR equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual T and transgender people. RA N by Lisa Mottet S G POLICY E and Justin Tanis N DER www.theTaskForce.org IN E QUALITY STITUTE NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY this page intentionally left blank opening the door to the inclusion of transgender people THE NINE KEYS TO MAKING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ORGANIZATIONS FULLY TRANSGENDER-INCLUSIVE by Lisa Mottet and Justin Tanis NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE National CENTER FOR TRANSGENDER EQUALITY OPENING THE DOOR The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedicated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender -

Crossdressing Cinema: an Analysis of Transgender

CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Major Subject: Communication CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Josh Heuman Aisha Durham Committee Members, Kristan Poirot Terence Hoagwood Head of Department, James A. Aune August 2012 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT Crossdressing Cinema: An Analysis of Transgender Representation in Film. (August 2012) Jeremy Russell Miller, B.A., University of Arkansas; M.A., University of Arkansas Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joshua Heuman Dr. Aisha Durham Transgender representations generally distance the transgender characters from the audience as objects of ridicule, fear, and sympathy. This distancing is accomplished through the use of specific narrative conventions and visual codes. In this dissertation, I analyze representations of transgender individuals in popular film comedies, thrillers, and independent dramas. Through a textual analysis of 24 films, I argue that the narrative conventions and visual codes of the films work to prevent identification or connection between the transgender characters and the audience. The purpose of this distancing is to privilege the heteronormative identities of the characters over their transgender identities. This dissertation is grounded in a cultural studies approach to representation as constitutive and constraining and a positional approach to gender that views gender identity as a position taken in a specific social context. -

10 Tips for Working with Transgender Patients

Introduction to the transgender community MEDICAL PROTOCOLS The World Professional Association for Gender identity is our internal understanding of Transgender Health (WPATH) publishes our own gender. We all have a gender identity. Standards of Care for the treatment of The term “transgender” is used to describe people gender identity disorders, available at whose gender identity does not correspond to their www.wpath.org. These internationally rec- birth-assigned sex and/or the stereotypes asso- ognized protocols are flexible guidelines ciated with that sex. A transgender woman is a designed to help providers develop individ- woman who was assigned male at birth and has ualized treatment plans with their patients. 10 Tips for Working a female gender identity. A transgender man is a man who was assigned female at birth and has a Another resource is the Primary Care Proto- with Transgender male gender identity. col for Transgender Patient Care produced by Center of Excellence for Transgender Patients For many transgender individuals, the lack of con- Health at the University of California, San An information and resource publication gruity between their gender identity and their Francisco. You can view the treatment birth sex creates stress and anxiety that can lead protocols at www.transhealth.ucsf.edu/ for health care providers to severe depression, suicidal tendencies, and/or protocols. These protocols provide accu- increased risk for alcohol and drug dependency. rate, peer-reviewed medical guidance on Transitioning - the process that many transgen- transgender health care and are a resource der people undergo to bring their outward gender for providers and support staff to improve expression into alignment with their gender iden- treatment capabilities and access to care tity - is for many medically necessary treatment for transgender patients. -

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

Concealed Or Denied Pregnancy

Concealed or denied pregnancy Finlay F1, Marcer H1, Baverstock A2 1Child Health Department, Newbridge Hill, Bath BA1 3QE 2Paediatric Department, Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton TA1 5DA Review Article Word Count 2,491 References 21 Concealed or denied pregnancy Finlay F, Marcer H, Baverstock A Introduction A 23 year old lady presented in labour with a concealed pregnancy. An ambulance was called to her home but unfortunately the baby died following complications secondary to delivery. ‘Rapid Response Procedures’ were set in motion and subsequent actions focused on appropriate physical and psychological care for the mother, along with multi agency safeguarding discussions. On reflection this case posed some interesting and challenging questions including -How common is a concealed pregnancy? What are the characteristics of women who have a concealed pregnancy? What are the risks/outcomes for the mother and the baby? And perhaps the biggest dilemma, what is the appropriate response from health professionals when a concealed or denied pregnancy is suspected? Due to the challenges we faced in managing this case we undertook a literature review to try to answer some of these questions Literature review Definitions A concealed pregnancy is described as one in which a woman knows that she is pregnant but does not tell anyone, or those who are told collude and conceal the fact from health professionals. A denied pregnancy is when a woman is unaware of, or unable to accept the fact that she is pregnant. Although the woman may be intellectually aware that she is pregnant she may continue to think, feel and behave as though she is not. -

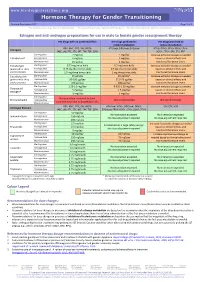

Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 for Personal Use Only

www.hiv-druginteractions.org Hormone Therapy for Gender Transitioning Revised September 2017 Page 1 of 2 For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. For personal use only. Not for distribution. Estrogen and anti-androgen preparations for use in male to female gender reassignment therapy HIV drugs with no predicted effect HIV drugs predicted to HIV drugs predicted to inhibit metabolism induce metabolism RPV, MVC, DTG, RAL, NRTIs ATV/cobi, DRV/cobi, EVG/cobi ATV/r, DRV/r, FPV/r, IDV/r, LPV/r, Estrogens (ABC, ddI, FTC, 3TC, d4T, TAF, TDF, ZDV) SQV/r, TPV/r, EFV, ETV, NVP Starting dose 2 mg/day 1 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Estradiol oral Average dose 4 mg/day 2 mg/day based on clinical effects and Maximum dose 8 mg/day 4 mg/day monitored hormone levels. Estradiol gel Starting dose 0.75 mg twice daily 0.5 mg twice daily Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 0.75 mg three times daily 0.5 mg three times daily based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 1.5 mg three times daily 1 mg three times daily monitored hormone levels. Estradiol patch Starting dose 25 µg/day 25 µg/day* Increase estradiol dosage as needed (preferred for >40 y Average dose 50-100 µg/day 37.5-75 µg/day based on clinical effects and and/or smokers) Maximum dose 150 µg/day 100 µg/day monitored hormone levels. Starting dose 1.25-2.5 mg/day 0.625-1.25 mg/day Increase estradiol dosage as needed Conjugated Average dose 5 mg/day 2.5 mg/day based on clinical effects and estrogen† Maximum dose 10 mg/day 5 mg/day monitored hormone levels. -

Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People

Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People: Best Practices for Front-line Health Care Staff Updated Fall 2016 NATIONAL LGBT HEALTH EDUCATION CENTER A PROGRAM OF THE FENWAY INSTITUTE INTRODUCTION Front-line staff play a key role in creating a health care environment that responds to the needs of trans- gender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) people. Everyone, no matter their gender identity or expres- sion, appreciates friendly and courteous service. In addition, TGNC people have unique needs when in- teracting with the health care system. First and fore- most, many TGNC people experience stigma and dis- crimination in their daily lives, including when seeking health care. In light of past adverse experiences in health care settings, many fear being treated disre- spectfully by health care staff, which can lead them to delay necessary health care services. Additionally, the names that TGNC people use may not match those listed on their health insurance or medical records. Mistakes can easily be made when talking with pa- tients as well as when coding and billing for insurance. Issues and concerns from TGNC patients often arise at the front desk and in waiting areas because those are the first points of contact for most patients. These issues, however, are almost always unintentional and can be prevented by training all staff in some basic principles and strategies. This document was devel- oped as a starting point to help train front-line health care employees to provide affirming services to TGNC patients (and all patients) at their organization. What’s Inside Part 1 Provides background information on TGNC people and their health needs. -

Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis OCTOBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12695 Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction Nick Drydakis Anglia Ruskin University, University of Cambridge and IZA OCTOBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12695 OCTOBER 2019 ABSTRACT Trans People, Transitioning, Mental Health, Life and Job Satisfaction For trans people (i.e. people whose gender is not the same as the sex they were assigned at birth) evidence suggests that transitioning (i.e.