Understanding Practice: a Pilot to Compare Mathematics Educators’ and Special Educators’ Use of Purposeful Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Count: Evaluation of a Pilot Early Mathematics Program in Low

Let’s Count: Evaluation of a Pilot Early Mathematics Program in Low Socioeconomic Locations in Australia Bob Perry Ann Gervasoni Charles Sturt University Australian Catholic University <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Sue Dockett Charles Sturt University <[email protected]> The Let’s Count pilot early mathematics program was implemented in five early childhood educational contexts across Australia during 2011. The program used specifically formulated materials and workshops to enlist the assistance of early childhood educators to work with parents and other family members of children in their settings to help develop these children’s awareness, confidence and skills in early mathematics. The pilot program was evaluated by the authors of this paper using a multi-methods approach. The evaluation was focused on the success of the Let’s Count program in bringing early childhood educators, parents and other family members together, to enhance children’s mathematical engagement, learning outcomes and dispositions. Let’s Count is a new early mathematics program commissioned by The Smith Family to assist parents and other family members to help their young children aged 3-5 years notice, explore and talk about powerful mathematical ideas in ways that develop positive dispositions to learning as well as mathematical knowledge and skills. It relies on parents and other family members providing the opportunities for the children to engage with, talk about, and document the mathematics in their everyday lives, and to extend it in ways that are relevant to them. Let’s Count is not a mathematics teaching program. However, it does involve early childhood educators in the role of advisers to parents and family members of the children in their settings. -

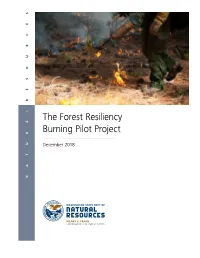

The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project

R E S O U C The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project December 2018 N A T U R L The Forest Resiliency Burning Pilot Project Report to the Legislature December 2018 Prepared by Washington State Department of Natural Resources and Washington Prescribed Fire Council Cover photo by © John Marshall. ii Executive Summary More than 100 years of fire suppression and land management practices have severely degraded Eastern Washington’s fire-adapted dry forests. Without the regular, low-intensity fires that created their open stand structure and resiliency, tree density has increased and brush and dead fuels have accumulated in the understory. The impact of these changes in combination with longer fire seasons have contributed to back-to-back record-breaking wildfire years, millions spent in firefighting resources and recovery, danger to our communities, and millions of acres of severely burned forest. Forest resiliency burning, also called prescribed fire or controlled burning, returns fire as an essential ecological process to these forests and is an effective tool for reducing fuels and associated risk of severe fires. Forest experts have identified 2.7 million acres of Central and Eastern Washington forests in need of restoration (Haugo et al. 2015). The agency’s 20-year Forest Health Strategic Plan addresses the need to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration treatments, which includes the use of prescribed fire. Successful implementation of prescribed fire in dry forest ecosystems faces a number of challenges, primarily unfavorable weather conditions, smoke management regulations, and some public opposition. Recognizing these challenges, the urgent need for large-scale forest restoration, and the usefulness and benefits of prescribed fire, the Legislature passed Engrossed Substitute House Bill (ESHB) 2928. -

Whole Crops Harvest Pilot Report Full-6

Supporting small-scale farmers to prevent in-field food loss. Hannah M. Semler, Whole Crops, Founder >>>> Introduction Across Maine’s foodshed, an estimated 25 million pounds of edible produce is left unharvested in fields.1 With more than 8,000 farms in Maine, the volume per crop is not easily visible, its value is not quantifiable, and the food systems that could absorb it such as processing for institutional kitchens, and donations programs, are underdeveloped or underincentivized. For more fresh nutritious produce to make it out of the field, a harvest-to-order, glean-to-donate concurrent Whole Crops Harvest (WCH) model is suggested in this pilot project report as an on-farm food loss prevention program. To create a secure market system that will warrant the efforts described in this report, of in-field measurement systems, online platform marketing tools, processing infrastructure and coordinated distribution systems, a larger statewide and regional approach is needed. The WCH Pilot was designed to support the USDA Local Food Promotions Project Grant “Scaling for Growth in the Greater Portland Area” with an opportunity to work with existing surplus production left in fields to de-risk the food systems solutions that were being tested by project partners. In fact, what the pilot illustrated was the need for a student agricultural workforce development effort to emerge statewide, reintroducing farm skills as an essential component of higher education and generational food security as a whole. 2 In Maine 65% of farms earn less than $10,000 per year. Many of these farms are extremely efficient in utilizing almost everything in the field, while others are learning the systems as new and beginning farmers. -

Airline and Business Jet Pilot Demand Outlook

Airline and Business Jet Pilot Demand Outlook 10-year view 2020 Update FOREWORD The civil aviation industry will require more than 260,000 new pilots over the next decade. Dear aviation colleagues, Today, our industry is facing unprecedented challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic is profoundly impacting day to day life, slowing down the global economy, and causing widespread disruption. The sudden drop in air travel demand has hindered the industry’s record growth trajectory. The consensus is that the road to recovery will span over several years. As the global aviation community looks ahead, many of us have acknowledged that our industry will have to overcome several funda- mental challenges. First and foremost, it is important to understand the ripple effects of the pandemic on the aviation industry. In March-April 2020, travel restrictions and border closures caused an abrupt decline in passenger air travel. Airlines and operators around the world have adjusted their operations to align with lower demand. Thousands of pilots have been furloughed in recent months. Many of them have pivoted to other professions and might not want to resume their pilot careers. On the one hand, airlines and operators have reduced the pilot workforce to offset the financial impact of the pandemic. On the other hand, data indicates that the industry will face significant challenges in the upcoming years to meet the demand for pilots. Despite the short-term decline in the number of active pilots, analysis shows that the civil aviation industry will require more than 260,000 new pilots over the next decade. As air travel resumes progressively over the next several years, the industry will experience upward mandatory retirement and attrition rates. -

A Quantitative Evaluation of Pilot-In-The-Loop Flying Tasks Using Power Frequency and NASA TLX Workload Assessment

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2014 A Quantitative Evaluation of Pilot-in-the-Loop Flying Tasks Using Power Frequency and NASA TLX Workload Assessment Antonio Gemma Moré University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Moré, Antonio Gemma, "A Quantitative Evaluation of Pilot-in-the-Loop Flying Tasks Using Power Frequency and NASA TLX Workload Assessment. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2739 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Antonio Gemma Moré entitled "A Quantitative Evaluation of Pilot-in-the-Loop Flying Tasks Using Power Frequency and NASA TLX Workload Assessment." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Engineering Science. Borja Martos, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Peter Solies, Steve Brooks Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) A Quantitative Evaluation of Pilot-in-the-Loop Flying Tasks Using Power Frequency and NASA TLX Workload Assessment A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Antonio Gemma Moré May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Antonio Gemma Moré All rights reserved ii DEDICATIONS I dedicate the work that follows to my grandfather Anthony Enrico Gemma. -

The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot

The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot Another way to describe “The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot” would be: “How to Overcome the Premise Pilot Blues.” A premise pilot literally establishes the premise of the show. Often they’re expository—it’s Maia’s first day at Diane’s law firm; the first time Mulder and Scully are working together; the day Cookie gets out of prison; when Walt decides he’s going to cook meth and potentially deal drugs. Premise pilots generally reset everything. When they work well, the creators take their time establishing the introduction into the world. We get the launch of the series in a nuanced, layered, slow burn way. I’m more satisfied by a pilot that has depth; there’s time for me to get to know the characters before throwing me into a huge amount of plotting. For me, character is always more important than plot. Once the characters are established, I’ll follow them anywhere. In 1996, when John Guare, the smart, prolific, outside-the-box playwright and screenwriter, published his first volume of collected works, he wrote a preface for the book The War Against the Kitchen Sink. One of the things Guare was rallying against was that desperate perceived need for realism, such as of drab objects in plays, when they could only ever be a construct. More interested in inner realities, !1 he grew curious in musicals, because there is no fourth wall. The actors interact with the audience, and Guare was intrigued by the connection between the audience and the actors on stage. -

DNA Collection in a Social Science Study: a Pilot Study of Peer Impacts on Attitudes and Drinking Behavior

DNA Collection in a Social Science Study: A Pilot Study of Peer Impacts on Attitudes and Drinking Behavior Jonathan K. Daw 1 , Hedwig Lee 1 , Amy Lucas 1 , Craig Owen 1 , and Emily McKendry- Smith 1 1 Department of Sociology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC 27599 • Key Words: DNA collection, saliva, genetic studies, social survey • Direct correspondence to: Guang Guo, CB#3210, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3210. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT. We report the experiences and participation rates of a pilot study (involving 200 individuals) of college drinking behavior incorporating both web survey and DNA collection components. Of the eligible sample, 78% completed the web survey, and 83.2% of those submitted DNA samples, for an overall participation rate of 64.9%. No evidence of lower participation rates along gender or racial/ethnic lines was observed, although there is some suggestive evidence of different levels of participant comfort with the process by race/ethnicity. Our experiences indicate that genetic data can be successfully collected for social science studies. We provide details of experiences in the data collection process and offer recommendations to inform future endeavors in DNA collection. 2 Social scientists today increasingly acknowledge and investigate the potential role of biological factors in relevant social processes (Committee on Population 2001; HERNANDEZ et al. 2006). Studies incorporating genetic variation into the study design – whether implicitly through twin studies, or explicitly through the use of molecular genetic information – hold the potential to separate the roles of social and biological factors in human behaviors of interest to sociologists. -

112508NU-Ep512-Goldenrod Script

“Jacked” #512/Ep. 91 Written by Don McGill Directed by Stephen Gyllenhaal Production Draft – 10/30/08 Rev. FULL Blue – 11/6/08 Rev. FULL Pink – 11/11/08 Rev. Yellow – 11/13/08 Rev. Green – 11/17/08 Rev. Goldenrod – 11/25/08 (Pages: 48.) SCOTT FREE in association with CBS PARAMOUNT NETWORK TELEVISION, a division of CBS Studios. © Copyright 2008 CBS Paramount Network Television. All Rights Reserved. This script is the property of CBS Paramount Network Television and may not be copied or distributed without the express written permission of CBS Paramount Network Television. This copy of the script remains the property of CBS Paramount Network Television. It may not be sold or transferred and must be returned to: CBS Paramount Network Television Legal Affairs 4024 Radford Avenue Administration Bldg., Suite 390, Studio City, CA 91604 THE WRITING CREDITS MAY OR MAY NOT BE FINAL AND SHOULD NOT BE USED FOR PUBLICITY OR ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT FIRST CHECKING WITH TELEVISION LEGAL DEPARTMENT. “Jacked” Ep. #512 – Production Draft: Rev. Goldenrod – 11/25/08 SCRIPT REVISION HISTORY COLOR DATE PAGES WHITE 10/30/08 (1-58) REV. FULL BLUE 11/6/08 (1-58) REV. FULL PINK 11/11/08 (1-59) REV. YELLOW 11/13/08 (1,3,4,6,10,11,17,18,19, 21,25,27,29,30,30A,40,42, 47,49,49A,50,51,53,55, 55A,56,56A,57,59,60.) REV. GREEN 11/17/08 (3,6,19,21,35.) REV. GOLDENROD 11/25/08 (48.) “Jacked” Ep. #512 – Production Draft: Rev. FULL Pink – 11/11/08 CAST LIST DON EPPES CHARLIE EPPES ALAN EPPES DAVID SINCLAIR LARRY FLEINHARDT AMITA RAMANUJAN COLBY GRANGER LIZ WARNER TIM KING BUCKLEY LEN WALSH JACK SHULER/HAWAIIAN SHIRT GUY CAITLIN TODD BUS DRIVER MOTHER BUS TECH N.D. -

Pilots and Pilotage in District Three Massachusetts

995 CMR: PILOT COMMISSIONERS 995 CMR 4.00: PILOTS AND PILOTAGE IN DISTRICT THREE MASSACHUSETTS Section 4.01: Purpose, Authority and Scope 4.02: Definitions 4.03: Public Information and Access 4.04: Number of Commissions 4.05: Types of Commissions 4.06: Application for Pilot Commissions 4.07: Application for Transit Pilot Commission 4.08: Application for Warrant Pilot Commission 4.09: Application for Full Branch Pilot Commission 4.10: Prior Maritime Experience 4.11: Veteran's Sea Time Credit 4.12: Examination Transit Pilot and Warrant Pilot Commissions 4.13: Examination Full Branch Pilot 4.14: Licenses and Certificates 4.15: Health and Medical Examination 4.16: Commissions 4.17: Restrictions on Commissions 4.18: Duties of Pilots 4.19: Pilot Organization 4.20: Pilot Boats 4.21: Pilot Boarding Areas 4.22: Bonds of Pilots 4.23: Reports to Commissioner 4.24: Miscellaneous 4.25: Emergency Waiver 4.01: Purpose, Authority and Scope (1) 995 CMR 4.00 is promulgated by the Deputy Commissioner for Massachusetts Pilot District Three pursuant to M.G.L. c. 103, §§ 3 and 21. 995 CMR 4.00 is intended to promote the safety of navigation in Massachusetts Pilot District Three, avoid interruption to navigation within the area and to prevent damage to the marine environment and other coastal natural resources of the region. (2) The Commissioner shall exercise all authority as provided in M.G.L. c. 103. (3) 995 CMR 4.00 applies to and is binding upon persons who are authorized to and who actually perform pilotage services upon the waters of District Three in Massachusetts under M.G.L. -

Analysis of the Airline Pilot Shortage

Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research Analysis of the Airline Pilot Shortage Victoria Crouch Abstract The pilot shortage in the United States currently affects airlines and pilots drastically. The airlines have been forced to implement new solutions to recruit and retain pilots. These solutions include dramatic pay raises and cadet programs. One of the most significant causes of the pilot shortage is the aviation industry’s rapid growth. Other factors include the aging pilot popula- tion and high flight training costs. In addition, regional airlines, a major source of pilots for major airlines, have a historically low pay rate, which deters pilots from wanting to work for them. This situation is compounded by a lack of hiring in the 2000s for various reasons. The effects of the pilot shortage include decreased flights, loss of revenue, and closing of some re- gional airlines. Airlines have implemented various solutions aimed at increasing the number of pilots. These include an increased pay rate, job pathway programs through universities, and guaranteed interviews or jobs. The solutions proposed will likely prove their effectiveness in minimizing the pilot shortage over the next decade. Note: This research was correct prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has affected the airline industry. 92 Spring 2020 Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research A global pilot shortage currently affects not only pilots but also their employ- ers. As a result, commercial airlines are forced to ground aircrafts because there are not enough pilots to fly them. Analysts project that the airlines will be short 8,000 pilots by 2023 and 14,139 pilots by 2026 (Klapper and Ruff-Stahl, 2019). -

Bark-Char Methods

MASTER'S THESIS RELEASE I authorize the University of Kentucky Libraries to reproduce this thesis in whole or in part for purposes of research. Signed:______________________________________ Date:________________________________________ 1 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Above all I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mary Arthur, for her incredible support and confidence in me. I also thank Dr. David Loftis and Rex Mann (co PI's) for their efforts in developing this study of the long term effects of landscape scale prescribed fire which was made possible through a grant funded by the USDA – USDI Joint Fire Science Program. I would like to thank the Daniel Boone National Forest and Morehead District personnel, particularly David Manner, Mike Colgan, and David Mertz, for their work in conducting the prescribed fires. I am indebted to Jeff Lewis for his help in setting out fuel moisture sticks, pyrometers, and recording fire weather. I greatly appreciated the suggestions I received from my committee members, Dr. Lynne Reiske- Kinney and Dr. Paul Kalisz. Thank you to everyone who worked on this project and helped me collect field data and process samples particularly: Stephanie, Beth, Autumn, Peter, Daniel, Bethany, Claudia, Eric A., and Jessi. Thanks to Millie Hamilton for helping us stay organized, equipped, and putting up with all my samples. Many thanks to Jessi Lyons for her help during the final semester of field work and data processing. It's nice knowing that I'm leaving the project in good hands. Thanks and good luck to my colleague Stephanie Green; I've enjoyed working and getting to know her over the past 2 years. -

Report to Congressional Armed Services Committees on Initiatives for Mitigating Military Pilot Shortfalls

REPORT TO CONGRESSIONAL ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEES ON INITIATIVES FOR MITIGATING MILITARY PILOT SHORTFALLS Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness January 16, 2019 The estimated cost of this report for the Department of Defense is approximately $113,000.00 in Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019. This includes $0 in expenses and $113,000.00 in Department labor. RefID: 8-6DDC5D6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 1 Background ............................................................................................................... 5 The Military Services .............................................................................................. 5 The Commercial Aviation Industry ........................................................................ 9 Seven Reporting Elements ................................................................................... 10 1: Viability of and Resource Requirements for Increasing Aviator Production .. 10 2 & 3: Manning Requirements and Aircraft Fleet Capacity Review ................... 13 4 & 5: Quality of Service and Quality of Life Initiatives ..................................... 18 6: Dedicated Flying Career Track ......................................................................... 22 7: Partnerships for Pilot Production Synergies ..................................................... 23 Conclusion ..............................................................................................................