Were Any of the Founders Deists?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyman Trumbull: Author of the Thirteenth Amendment, Author of the Civil Rights Act, and the First Second Amendment Lawyer

KOPEL (1117–1192).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/2/16 4:20 PM Lyman Trumbull: Author of the Thirteenth Amendment, Author of the Civil Rights Act, and the First Second Amendment Lawyer David B. Kopel* This Article provides the first legal biography of lawyer and Senator Lyman Trumbull, one of the most important lawyers and politicians of the nineteenth century. Early in his career, as the leading anti-slavery lawyer in Illinois in the 1830s, he won the cases constricting and then abolishing slavery in that state; six decades later, Trumbull represented imprisoned labor leader Eugene Debs in the Supreme Court, and wrote the Populist Party platform. In between, Trumbull helped found the Republican Party, and served three U.S. Senate terms, chairing the judiciary committee. One of the greatest leaders of America’s “Second Founding,” Trumbull wrote the Thirteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Act, and the Freedmen’s Bureau Act. The latter two were expressly intended to protect the Second Amendment rights of former slaves. Another Trumbull law, the Second Confiscation Act, was the first federal statute to providing for arming freedmen. After leaving the Senate, Trumbull continued his fight for arms rights for workingmen, bringing Presser v. Illinois to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1886, and Dunne v. Illinois to the Illinois Supreme Court in 1879. His 1894 Populist Party platform was a fiery affirmation of Second Amendment principles. In the decades following the end of President James Madison’s Administration in 1817, no American lawyer or legislator did as much as Trumbull in defense of Second Amendment. -

Ideals of American Life Told in Biographies and Autobiographies Of

MEN OF MAKK IN CONNECTICUT Men of Mark in Connecticut IDEALS OF AMERICAN LIFE TOLD IN BIOG- RAPHIES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES OF EMINENT LIVING AMERICANS EDITED BY COLONEL N. G. OSBORN M EDITOK "NEW HAVEN JOURNAL AND COURIER" VOLUME II WILLIAM R. GOODSPEED HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 1906 Copyright 1904 by B. F. Johnson [uLIBKARYofOONef-JESSj Two Copies nhcui^j. AFK 14 1908 The Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, Hartford, Conn. MEN OF MARK IN CONNECTICUT Col, N. G. Osborn, Editor-in-Chief ADVISORY BOARD HON. WILLIAM S. CASE . Hartfobd JIIBGE OF SI7FKBI0B COUBT HON. GEORGE S. GODAED Hartford STATE lilBBABIAK HON. FREDERICK J. KINGSBURY, LL.D. Waterbukt MEMBER CORPORATION TALE UNIVEESITr CAPTAIN EDWARD W. MARSH . Bridgeport TREASUEEB PEOPLE'S SAVINGS BANK COL. N. G. OSBORN New Haven editor new haten begisteb HON. HENRY ROBERTS Hartford EX-OOyEBNOR. HON. JONATHAN TRUMBULL Norwich T.TBBARTAN FT7BLIC LIBRARY WILLIAM KNEELAND TOWNSEND TOWNSEND, JUDGE WILLIAM KNEELAND, of the United States Circuit Court, comes of a family that long has held a prominent place in the university town of New Haven, where he was born June 12th, 1848. He is the son of James Mulford and Maria Theresa Townsend. He was fond of his books and of the companionship of good friends as well, and youthful characteristics have remained constant. Gradu- ated from Yale in 1871, in a class that gave not a few eminent men to the professions, he continued his studies in the Yale Law School, along the line which nature seemed to have marked out for him. In 1874 he received the degree of LL.B, and immediately was admitted to the bar in New Haven County, and entered upon the practice of his pro- fession. -

The Governors of Connecticut, 1905 >>

'tbe TWENTIETH GOVERNOR of CONNECTICUT •was the second JONATHAN TRUMBULL A son of the famous " war governor" born in Lebanon, graduated from Harvard Col lege, and a member of the General Assem bly at the outbreak of the Revolution — He entered the conflict and was chosen private secretary and first aid to General Washing ton, becoming second speaker of the House of Representatives, a member of the United States Senate, and governor of Connecticut for eleven consecutive years JONATHAN T RUMBULL, 2nd HE s econd Jonathan Trumbull was one of the governors of this c ommonwealth that acquired a national reputation. Born at L ebanon, on March 26, 1740, he was the second son of Jonathan Trumbull, the famous "war governor." He prepared for and entered Harvard College in 1 755 at the age of fifteen years. • While a college student he had a reputation for scholarly ability that followed him throughout his career. Whene h was graduated with honors in 1 759, a useful and patri otic career was predicted by his friends. Settling in Lebanon, Trum bull was soon elected a member of the General Assembly, and was in that body when the Revolutionary War opened. He immediately entered into the conflict with the same strong spirit of determination which characterized his life afterward. The Continental Congress appointed Trumbull paymaster-general of the northern department of the Colonial army under General Washington. This position he filled with such thorough satisfaction to the commander-in-chief, that in 1781 Trumbull was selected to succeed Alexander Hamilton as private secretary and first aid to Major General Washington. -

SUSQUEHANNAH SETTLERS Hartford Connecticut State Library

CO}DCTICUT ARCHIVES SUSQUEHANNAH SETTLERS SEC0} SERIES, 1771-1797 WESTERN LANDS SECOND SERIES, 1783-1819 ONE VOLUME AND INDEX Hartford Connecticut State Library 1944 Note Among the Connecticut Archives are files of the General Assembly up to 1820. About 1845 Sylvester Judd, author of the History of Hadley, Massa- chusetts, selected and arranged documents from these files up to the year 1790 in one hundred and twenty-two volumes. The documents from 170 through 180 were transferred from the office of the Secretary of State when our new State Library and Supreme Court building was occupied. It is principally from the last mentioned documents that the material on Susquehannah Settlers and Western Lands, Second Seri, was taken, with the addition of a few documents of the earlier period, omitted by Mr. Judd from the First Series. The earliest date in the material on Susquehannah Settlers is May 1771, on a resolve which concerns the collecting of evidence in regard to Connecticut’s title to lands west of the Delaware River; and the latest date is October 1797, on a resolve authorizing the comptroller to draw an order in favor of commissioners for-receiving the college grant. The earliest date in the material on Western Lands is January i785, on a resolve concerning cession of this state’s rights to the Western Lands to the United States; and the latest date is May 1819, on an act relative to the books, records and papers of the late Connecticut Land Company. There are one hun- dred and sixty-ne documents in the Second Series of Susquehannah Settlers and Western Lands. -

The Governors of Connecticut, 1905

ThegovernorsofConnecticut Norton CalvinFrederick I'his e dition is limited to one thousand copies of which this is No tbe A uthor Affectionately Dedicates Cbis Book Co George merriman of Bristol, Connecticut "tbe Cruest, noblest ana Best friend T €oer fia<T Copyrighted, 1 905, by Frederick Calvin Norton Printed by Dorman Lithographing Company at New Haven Governors Connecticut Biographies o f the Chief Executives of the Commonwealth that gave to the World the First Written Constitution known to History By F REDERICK CALVIN NORTON Illustrated w ith reproductions from oil paintings at the State Capitol and facsimile sig natures from official documents MDCCCCV Patron's E dition published by THE CONNECTICUT MAGAZINE Company at Hartford, Connecticut. ByV I a y of Introduction WHILE I w as living in the home of that sturdy Puritan governor, William Leete, — my native town of Guil ford, — the idea suggested itself to me that inasmuch as a collection of the biographies of the chief executives of Connecticut had never been made, the work would afford an interesting and agreeable undertaking. This was in the year 1895. 1 began the task, but before it had far progressed it offered what seemed to me insurmountable obstacles, so that for a time the collection of data concerning the early rulers of the state was entirely abandoned. A few years later the work was again resumed and carried to completion. The manuscript was requested by a magazine editor for publication and appeared serially in " The Connecticut Magazine." To R ev. Samuel Hart, D.D., president of the Connecticut Historical Society, I express my gratitude for his assistance in deciding some matters which were subject to controversy. -

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

Connecticut Project Helper

Connecticut Project Helper Resources for Creating a Great Connecticut Project From the Connecticut Colonial Robin and ConneCT Kids! Connecticut State Symbols Famous Connecticut People Connecticut Information and Facts Famous Connecticut Places Connecticut Outline Map Do-it-Yourself Connecticut Flag Six Connecticut Project Ideas Connecticut Postcard and more…. www.kids.ct.gov What Makes a Great Connecticut Project? You! You and your ability to show how much you have learned about Connecticut. So, the most important part of your project will not be found in this booklet. But, we can help to give you ideas, resources, facts, and information that would be hard for you to find. Some students are good at drawing and art, some students are good at writing reports, and some students are good at crafts and other skills. But that part of the project will be only the beginning. A great Connecticut Project will be the one where you have become a Connecticut expert to the best of your abilities. Every State in the United States has a special character that comes from a unique blend of land, people, climate, location, history, industry, government, economy and culture. A great Connecticut Project will be the one where you can answer the question: "What makes Connecticut special?" In addition to this booklet, you should look for Connecticut information in your school library or town library. There are many online resources that can be found by doing internet searches. The more you find, the easier it will be to put together that Great Connecticut Project! The Connecticut Project Helper is produced and distributed by The ConneCT Kids Committee, and is intended for educational purposes only. -

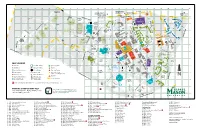

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science FEATURE: WORTH NOTING USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library 19.1. and Archival Science portal Danielle Mihram and Curtis Fletcher publication, abstract: USC Digital Voltaire, a digital, multimodal critical edition of autograph letters, aims to combine the traditional scope of humanities inquiry with the affordancesfor and methodologies of digital scholarship, and to support scholarly inquiry at all levels, beyond the disciplines associated with Voltaire and the Enlightenment. Digital editing, and digital editions in particular, will likely expand in the next few decades as a multitude of assets become digitized and made available as online collections. One important question is: What role will librarians and archivists play in this era? USC Digital Voltaire points in one possible, creativeaccepted direction. and Voltaire’s Autograph Letters at USC edited, t the University of Southern California (USC) Special Collections Department, researchers can findcopy 31 original (autograph) letters and four poems covering the years 1742 to 1777 by Voltaire, the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, A1694–1778. Voltaire’s clear writing style, humor, and sharp intelligence made him one of the greatest writers of the French Enlightenment, a period of intellectual ferment in the late 17th and the 18th centuries. His correspondents included other leading figures of the Enlightenment,reviewed, such as the mathematician and philosopher Jean le Rond d’Alembert; Frederick II (Frederick the Great), king of Prussia; and Madame de Pompadour, the mistresspeer of King Louis XV of France. Voltaire’s voluminous correspondence currently comprisesis over 22,000 published letters, of which 16,136 are by Voltaire.1 The correspon- dence offers a multifaceted, private, and, at times, moving expression of the writer’s mss.innermost thoughts and feelings, through epistolary exchanges. -

Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 25 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 1997 1-1-1997 Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R. Grodin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph R. Grodin, Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety, 25 Hastings Const. L.Q. 1 (1997). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol25/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety By JOSEPH R. GRODIN* Most people, at least most lawyers, are aware that of the trilogy of rights made famous by the Declaration of Independence-life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness-only the first two made it into the Federal Con- stitution, felicity giving way, in the Fifth Amendment's due process clause, to a more sober concern for the rights of property.1 What most people, even most lawyers, are less likely to know is that fully two thirds of the state constitutions contain provisions which either declare the right of per- sons to pursue happiness or (along with safety) to actually "obtain" it. Scholars, as well as lawyers, have tended to ignore these state consti- tutional provisions, apparently regarding them as little more than pious echoes of the Declaration.