2012 Erin Cassidy Pinkston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Sarles Resume

Bob Sarles [email protected] (415) 305-5757 Documentary I Got A Monster Editor. True crime feature documentary. Directed by Kevin Abrams. Alpine Labs. The Nine Lives of Ozzy Osbourne Producer, editor. An A&E documentary special. Osbourne Media. Born In Chicago Co-director, Editor. Feature documentary. Shout! Factory/Out The Box Records. Mata Hari The Naked Spy Editor. Post Production Producer. Feature documentary. Red Spoke Films. BANG! The Bert Berns Story Co-director (with Brett Berns), editor. Theatrically released feature documentary. Sweet Blues: A Film About Mike Bloomfield Director, Editor. Produced by Ravin’ Films for Sony Legacy. Moon Shot Editor. Documentary series produced for Turner Original Productions and aired on TBS. Peabody Award recipient. Two Primetime Emmy nominations: editing and outstanding documentary. The Story of Fathers & Sons Editor. ABC documentary produced by Luna Productions. Unsung Editor. Documentary television series produced by A.Smith & Company for TV One. Behind The Music Producer and Editor. Documentary television series produced by VH1. Digital Divide Series Editor. PBS documentary series produced by Studio Miramar. The True Adventures of The Real Beverly Hillbillies Editor. Feature documentary. Ruckus Films. Wrestling With Satan Co-Producer, editor. Feature documentary. Wandering Eye Productions. Feed Your Head Director, editor. Documentary film produced for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland. Yo Cip! Director, Editor. Documentary short. A Ravin’ Film for Cipricious Productions. Produced by Joel Peskin. Coldplay Live! At The Fillmore Director, editor. Television series episode produced by BGP/SFX. Take Joy! The Magical World of Tasha Tudor Editor. Documentary. Aired on PBS. Spellbound Prods. Teen People Presents 21 Stars Under 21 Editor. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

WE Tv ANNOUNCES AMBITIOUS SLATE of UNSCRIPTED

WE tv ANNOUNCES AMBITIOUS SLATE OF UNSCRIPTED ORIGINALS FOR 2014/15, INCLUDING A PILOT OF “CHARLIE SHEEN’S BAD INFLUENCE” – A NEW RELATIONSHIP-BASED COMPETITION SHOW – ALONGSIDE NEW AND RETURNING SERIES New Shows “Match Made in Heaven” and “Mystery Millionaire” Join WE tv’s Growing Line-Up of Fan Favorites Starring Kendra Wilkinson-Baskett, Tamar Braxton and David Tutera Popular “Marriage Boot Camp” Franchise Returns with an All-New Reality Stars Edition Featuring JWoww, Trista & Ryan Sutter and More WE tv’s First Scripted Series, “The Divide,” Premieres This July NEW YORK, NY – April 10, 2014 – WE tv today announced an ambitious slate of unscripted original programming for 2014/15 including a one-hour pilot of “Charlie Sheen’s Bad Influence,” a fun, relationship-based competition show. The network also greenlit the new series “Match Made In Heaven,” “Mystery Millionaire” and “David Tutera’s CELEBrations” and renewed the popular shows “Kendra on Top,” “Marriage Boot Camp” and the “Braxton Family Values” spinoff “Tamar & Vince,” further strengthening WE tv’s line-up of unscripted programming focused on strong, relatable characters set against the backdrop of dramatic, real-life situations. In addition to the network’s growing unscripted efforts, WE tv will debut its first original scripted series, “The Divide,” this July. WE tv is off to a solid start in 2014. Its newest breakout hit “SWV Reunited” averaged 1.2 million viewers and the popular docu-series “Mary Mary” is currently delivering 1.1 million viewers per episode. On Thursday nights, WE tv ranks as a top women’s network due to its successful line-up of original programming, and the network has significantly expanded its social media following and presence over the last year. -

Junior Olympians

I Saw It In ... Nashville N The News N THURSDAY • JULY 26, 2012 • Issue 60 • 2 Sections • 14 Pages • In Howard County, Arkansas since 1878 • USPS 371-540 • 75 cents IN BRIEFt School facing 12 percent cut in federal funds Fourth CHARLES GOODIN bers Monday during their regular gress fails to pass a budget with ditionally disadvantaged students. Managing Editor meeting. $1.2 trillion in cuts and opts instead “If we undergo a 12 percent cut Friday Graham said the reduction could to increase the federal debt by the that means you’re either gonna NASHVILLE - The school district come as part of sequestration same amount. eliminate your federal programs singing could face cuts in federal funding brought about by the Budget Con- Locally, Graham said that means or pay for them with local money,” as high as 12 percent in the coming trol Act of 2011, which requires a large reduction in Title I spend- Graham explained. scheduled school year, Superintendent Doug automatic budget cuts for each ing, which is usually geared toward To prepare for the cuts, Graham Graham warned school board mem- department in the event that con- improving the achievement of tra- See FUNDS / Page 6 Liberty Bap- tist Church will host its regular 4th Friday Sing- ing July 27 at 6:30 p.m. A pot- Nashville luck supper will be served. For more informa- wins best tion call 870- 451-3389. water award DEWAYNE HOLLOWAY Beneit Sports Editor dinner NASHVILLE – Public Works Director Larry Dunaway an- this nounced that Nashville was awarded the best drinking weekend water in Arkansas as he re- ported on several projects in There will be the water and street depart- a benefit meal ments during the monthly city for Onie and council meeting held Tues., Heath Morris. -

06 9-3-13 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 3, 2013 Monday Evening September 9, 2013 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Shark Tank Mistresses Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 6 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 12 KBSH/CBS How I Met Two Men 2 Broke G Big Bang Under the Dome Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC Million Second Ninja Warrior Siberia Local Tonight Show w/Leno J. Fallon FOX Bones Local Cable Channels A&E Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage AMC Lord of the Rings Lord of the Rings ANIM Wildman Wildman Gator Boys Gator Boys Wildman Wildman Gator Boys CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Live Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Live DISC To Be Announced Fast N' Loud To Be Announced Fast N' Loud To Be Announced DISN Camp Rock Jessie Good Luck Austin Jessie Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News Hello 13 Going on 30 Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 World Series World Series Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann FAM The Siste The Princess Diaries The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Kung Fu Panda Kung Fu Panda HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunt Intl Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST American Pickers American Pickers American Pickers God, Guns God, Guns American Pickers LIFE A Sister's Nightmare She Made Them Do It A Sister's Nightmare Listings: MTV Teen Mom 3 Teen Mom 3 Teen Mom 3 Teen Mom 3 NICK Awesome Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se The Nanny The Nanny Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI The Bourne Ultimatum Quantum of Solace For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail TBS Fam. -

1-2 Front CFP 7-2-12.Indd

Page 2 Colby Free Press Monday, July 2, 2012 Area/State Weather Kansas schools expect less money Briefly Firm collecting for From “SCHOOLS,” Page 1 school year is 11.2 percent,” She reported the school dis- each. Milk prices will stay the said Harrison. “This equals $575 trict’s preliminary cash summary same. victims of Colorado fire More students are completing of the base state aid for Colby and year-end balance estimates • Decided that activity fees Toni Lindberg and HomeLand Re- high school than ever before and Schools.” to the school board, saying the and textbook fees for the 2012- alty and Auction are taking nonperish- Kansas schools have the high- This projection is $743 mil- general fund’s average balance 13 school year will remain the able donations for families affected by est college prep test scores and lion below the available revenue is about $6.194 million and same. Harrison said they were the Waldo Canyon Fire in Colorado participation rates on record. for fi scal year 2013, Tallman 2011-12 estimated expenditures both increased last year. Springs. A trailer will be stopping in Harrison said adult education reported. The drop is caused are $6.189 million. • Agreed to a request from Colby early Wednesday morning to col- attainment is at an all-time high, by expiration of the 1 percent DeYoung added that although Jarrod Spencer on behalf of the lect supplies and deliver them to the vic- with expanded opportunities sales tax increase enacted under her report shows the fund bal- Thomas County Ministerial Al- tims. -

Saturday Morning, Sept. 28

SATURDAY MORNING, SEPT. 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sat (N) (cc) College Football. (N) (Live) 2/KATU 2 2 5:00 CBS This Morning: Saturday Lucky Dog (N) Dr. Chris Pet Vet Recipe Rehab (N) Garden Time All In With Laila Game Changers Paid Paid Lucas Oil Off Road Racing (Taped) 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) (TVG) (N) (TVG) (TVG) Ali (N) (TVG) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Sunrise at 7:00 The Chica Show LazyTown (cc) Tree Fu Tom Justin Time English Premier League Soccer Swansea City AFC vs Arsenal FC. (N) Red Bull Signa- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) AM (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (Live) (cc) ture Series (N) Sesame Street The Flower Show. Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) SciGirls (cc) Cyberchase Fetch! With Ruff The Victory Gar- P. Allen Smith’s Sewing With It’s Sew Easy 10/KOPB 10 10 Stinky tries to relax. (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVG) (TVY) Ruffman (TVY) den Light. (TVG) Garden Home Nancy (TVG) (TVG) Good Day Oregon Saturday (N) MLB Player Poll MLB Pregame (cc) MLB Baseball (TVG) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVG) (TVG) Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Atmosphere for Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Miracles w/ The Lads TV (cc) Auto B. Good (cc) Come on Over God Rocks! (cc) Monstertruck Mary Rice Hop- Lassie (cc) Davey and Goliath Ishine Knect (cc) Mike’s Inspiration VeggieTales (cc) 3-2-1 Penguins! 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) (cc) (TVY7) (TVY) Adventures kins (TVG) (TVY) (TVG) Station (TVY) (cc) (TVY7) Paid Paid Adventures Rescue Heroes Sonic X (cc) Bolts & Blip The Spectacular Justice League Dragon Ball Z Kai B-Daman Cross- Yu-Gi-Oh! (cc) Yu-Gi-Oh! ZEXAL 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVY) (TVY7) (TVY7) Spider-Man Unlimited (TVY7) fire (N) (TVY7) (TVY7) Paid Paid Live Life and Win! Pets.TV (cc) Jack Hanna’s Into EA Sports Game Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 49/KPDX 13 13 (N) (TVG) (TVG) the Wild Time Paid Paid Criminal Minds Victims of the Criminal Minds Kevin thinks Gar- Criminal Minds Pay It Forward. -

Ibland Måste Jag Också Få Vara Lite Drama”

”Ibland måste jag också få vara lite drama” En genreanalys av Svenska Hollywoodfruar Av: Jon Wächter Handledare: Carina Guyard Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för kultur och lärande Kandidat/Magisteruppsats 15 hp Ämne | Medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap Vårterminen 2016 1 Sammanfattning Titel: “Ibland måste jag också få vara lite drama” – En genreanalys av Svenska Hollywoodfruar. Engelsk Titel: “Sometimes I need to be a little drama too” – A genre analysis of Swedish Hollywood wives. Författare: Jon Wächter Handledare: Carina Guyard Termin: Vårterminen 2016 Svenska Hollywoodfruar är en av Sveriges mest populära reality-serier. Serien följer de svenska Hollywoodfruarna och ger en inblick i deras glamourösa lyxlivsvardag men hur porträtteras egentligen kvinnorna som karaktärer med avseende på deras femininet? För det är just de svenska Hollywoodfruarna som skall porträtteras. Snarare än deras vardag är det framförallt fruarna som personer i rollen som hemmafru, f.d. hemmafru eller helt enkelt som kvinna som skall avspeglas i serien. Vidare undersöker jag handlingen i Svenska Hollywoodfruar skildras med avseende på genrens anspråk på realism? Och hur har serien förändrats från första till senaste säsongen? Dessa är frågor jag ämnar besvara genom att göra en genre analys av valda avsnitt av den första och senaste säsongen av Svenska Hollywoodfruar. Till min hjälp för att göra denna analys har jag i huvudsak använt mig av två teoretiska inriktningar: postfeminism (för att undersöka karaktärer och musik) samt diverse teorier om realism (för att undersöka handling samt kamera). Jag har även studerat tidigare forskningsartiklar som berör kvinnor och television, främst med koppling till den amerikanska versionen av Svenska Hollywoodfruar vid namn Real Housewives. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

1-2 Front CFP 8-9-12.Indd

Page 2 Colby Free Press Thursday, August 9, 2012 Area/State Weather Man leads chase Briefly College seeks input on strategic plan through Colby Colby Community College is seeking community comments on a proposed fi ve-year strategic plan. Anyone who’s residential blocks. He turned From “CHASE,” Page 1 interested is encouraged to read the plan west on Sixth, north again and on the college’s web site, www.colbycc. fi red at the man, apparently west on Eighth, a dead end. He edu, and e-mail comments to President missing, near the U.S. 83-U.S someone got on to the Kyle Steve Vacik at steve.vacik@colbycc. 40 junction. Railway tracks and tried to drive edu by Friday, Aug. 17. For information, The man drove north on U.S. west from K-25. call Debbie Schwanke at 460-5411. 83 with at least four troopers About a block west of the close behind. Speeds ranged highway crossing, he left the from 100 to 130 mph, slowing tracks and tried to get back to a Once a Month Lunch as the driver avoided traffi c. Of- street. His car was boxed in by coming up on Saturday fi cers reported that the man ap- trees, and he abandoned it. Offi - Once a Month Lunch will be served peared to be reaching under the cers found him under a pickup. from 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Saturday seat or in the back seat, like he Troopers, deputies and city of- in the basement of the Colby Presbyteri- was trying to fi nd a weapon. -

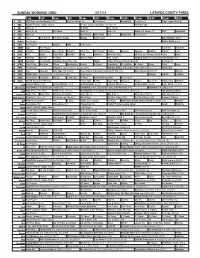

Sunday Morning Grid 5/11/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/11/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Major League Fishing 4 NBC English Premier League Soccer Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) Å PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) World of X Games (N) NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Mrs. Doubtfire ››› 13 MyNet Paid Program Men in Black ››› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program Transform. Transform. 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Train Your Dog 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Omni 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Tango & Cash ›› (1989) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de España 2014. Bedtime Stories ›› (2008) Adam Sandler. (PG) Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Peg Dinosaur Easy Yoga: The Secret Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) Masterpiece Mystery! Å Mystery 52 KVEA Fútbol Inglés: Manchester City vs West Ham United Paid Program Enfoque Noodle LazyTown 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

S Potluck Dinner Party’ Producer Sallyann Salsano Talks

‘Martha & Snoop’s Potluck Dinner Party’ Producer SallyAnn Salsano Talks About Her Hit Reality TV Shows & Possible ‘Jersey Shore’ Revival Interview by Lori Bizzoco. Written by Delaney Gilbride. The queen of reality TV, SallyAnn Salsano, has taken VH1 by storm and is back and better than ever! The self-made American television producer is the CEO and president of 495 Productions, which launched in 2006 and has been a success ever since. Salsano has produced a number of widely-loved television shows, including MTV’s Jersey Shore with its equally successful spin-off Snooki & JWoww. The entrepreneur has also produced popular reality TV series such as Friendzone, Party Down South, Blue Collar Millionaires, and the new VH1 show that everyone has been raving about, Martha & Snoop’s Potluck Dinner Party. Celebrity Interview with Reality TV Producer SallyAnn Salsano In our recent celebrity interview, Salsano opens up about the idea behind her latest project. She had collaborated with VH1 in the hopes of creating a new, unique show that viewers would fall in love with — and boy, did they! When speaking about the birth of Martha & Snoop’s Potluck Dinner Party, Salsano says the new president at VH1 asked her what kind of show she had been dying to create. She answered the question with an immediate response: “I would love to do a crazy, energetic celebrity cooking show,” which everyone at VH1 jumped right on board with. When going back and forth about who they wanted to co-star in the show, Salsano tells us she asked the room, “Why are we even discussing other people? I think Martha Stewart and Snoop Dogg would be the best show ever.” Related Link: Celebrity Interview: ‘Ex Isle’ Executive Producer SallyAnn Salsano Talks Reality TV After discussing the idea with the world-renowned chef, 495 Productions reached out to the rapper, but when they called him, he had already known about the show through Stewart.