Ian Robert James Jack 1923–2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L. Foster AG® [email protected] Origins of Scottish Surnames Surnames are said to have begun to be used by Scottish nobility at the direction of King Malcolm Ceannmor in about 1061. William L. Kirk, Jr. “Introduction to the Derivation of Scottish Surnames,” Clan Macrae (1992), http://www.clanmacrae.ca/documents/names.htm “In some Highland areas, though, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century, and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.” “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Types of Scottish Surnames Location-Based Surnames Some people were named for localities. For example, the surname “Murray from the lands of Moray, and Ogilvie, which, according to Black, derives from the barony of Ogilvie in the parish of Glamis, Angus. Tenants might in turn assume, or be given, the name of their landlord, despite having no kinship with him.” Sometimes surnames referred to a specific topographical feature of the landscape such as a river, a loch, a hill, etc. Some examples might include: Names that contain 'kirk' (as in Kirkland, or Selkirk) which means 'church' in Gaelic; 'Muir' or names that contain it (means 'moor' in Gaelic); A name which has 'Barr' in it (this means 'hilltop' in Gaelic). “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Occupational Surnames A significant amount of surnames come from occupations. So a smith became known as Smith or Gow (Gaelic for smith), a tailor became Tailor/Taylor, a baker was Baxter, a weaver was Webster, etc. “Surnames,”ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Descriptive Surnames “Nicknames were 'descriptional' ie. -

Claire Roberts Name: Ian Young Title: Professor Present Position And

Witness Statement Ref. No. 178/2 NAME OF CHILD: Claire Roberts Name: Ian Young Title: Professor Present position and institution: Professor of Medicine and Director of The Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast Previous position and institution: [As at the time of the child’s death] Membership of Advisory Panels and Committees: [Identify by date and title all of those between January 1995-August 2012] Previous Statements, Depositions and Reports: [Identify by date and title all those made in relation to the child’s death] OFFICIAL USE: List of previous statements, depositions and reports attached: Ref: Date: 096-007-039 Statement to the PSNI 091-010-060 4th May 2006 Deposition to the Coroner WS-178/1 14th Sep 2012 Inquiry Witness Statement 1 INQ - CR WS-178/2 Page 1 Response to reports of Dr.R MacFaul on Claire Roberts Professor Ian S.Young The purpose of this report is to respond to incorrect statements made by Dr MacFaul in relation to fluid management of Claire in 1996, which subsequently translate through to criticisms of the information given to Claire’s parents in 2004. I wish to highlight major factual errors in his original report, repeated throughout, which he corrects inadequately and to a limited extent in his supplementary report. Despite this limited correction, Dr MacFaul fails to withdraw criticisms based on the major factual errors which he has made. Factual errors in Dr.MacFaul’s report: Throughout his report Dr MacFaul repeatedly refers to the following information from the major paediatric textbook (Forfar and Arneil) in support of his statements and criticisms. -

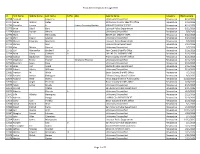

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Boys & Girls 1950 the Top 100 Names: 1950 Boys Girls 1 John

Boys & Girls 1950 The top 100 names: 1950 Boys Girls By rank Alphabetically By rank Alphabetically 1 John Adam 70 1 Margaret Agnes 10 2 James Adrian 97= 2 Elizabeth Aileen 72 3 William Alan 13 3 Mary Alexandra 53= 4 Robert Alasdair 86= 4 Catherine Alice 53= 5 David Alastair 47 5 Anne Alison 40 6 Thomas Albert 66 6 Linda Angela 84= 7 Alexander Alexander 7 7 Helen Ann 13 8 George Alfred 78 8 Patricia Anna 88= 9 Ian Alistair 31 9 Irene Anne 5 10 Brian Alister 94= 10 Agnes Annette 86 11 Andrew Allan 25 11 Kathleen Annie 29 12 Michael Andrew 11 12 Jean Audrey 92= 13 Alan Angus 48= 13 Ann Avril 88= 14 Peter Anthony 44 14 Maureen Barbara 27 15 Charles Archibald 40 15 Janet Brenda 47 16 Ronald Arthur 53 16 Sandra Bridget 100= 17 Gordon Bernard 65 17 Sheila Carol 30 18 Kenneth Brian 10 18 Christine Carole 99 19 Douglas Bruce 64 19 Jane Caroline 52 20 Joseph Bryan 86= 20 Marion Catherine 4 21 Donald Cameron 89= 21 Moira Christina 26 22 Edward Charles 15 22 Isabella Christine 18 23 Colin Christopher 50 23 Joan Doreen 61 24 Hugh Colin 23 24 June Dorothy 31 25 Allan Daniel 33 25 Frances Edith 84= 26 Richard David 5 26 Christina Eileen 33 27 Francis Denis 68 27 Barbara Elaine 58= 28 Patrick Dennis 52 28 Jennifer Eleanor 44 29 Raymond Derek 30 29 Annie Elizabeth 2 30 Derek Desmond 97= 30 Carol Ellen 55 31 Alistair Donald 21 31 Dorothy Evelyn 36 32 Henry Douglas 19 32 Susan Fiona 45 33 Daniel Duncan 38 33 Eileen Frances 25 34 Norman Edward 22 34 Sarah Georgina 67 35 Neil Eric 42 35 Joyce Gillian 92= 36 Iain Ernest 79= 36 Evelyn Grace 58= 37 Graham Francis -

Match Results 2019

Match List 2019 Last Name First Name Institution Specialty Abernethy Jane Hosp of the Univ of PA Medicine-Primary Aepli Savannah Pennsylvania Hospital Medicine-Preliminary Aepli Savannah Johns Hopkins Hosp-MD Anesthesiology Altaffer Ana Luiza Childrens Hosp-Philadelphia-PA Pediatrics Andersen Tomas Pennsylvania Hospital Medicine-Preliminary Andersen Tomas Scheie Eye Inst/U Penn Ophthalmology Arena John Hosp of the Univ of PA Neurological Surgery Argueso Dallas Hosp of the Univ of PA Internal Medicine Azan Alexander Montefiore Med Ctr/Einstein-NY Med-Primary/Social Int Med Bakir Basil Johns Hopkins Hosp-MD Internal Medicine Barnhart John UC San Francisco-CA Psychiatry Becker Andrew Hosp of the Univ of PA Anesthesiology Berger Ian Duke Univ Med Ctr-NC Urology Bernal Olivia Johns Hopkins/Bayview-MD Medicine-Primary Bindon Joshua U Massachusetts Med School Orthopaedic Surgery Bohorquez Dominique Jackson Memorial Hosp-FL Otolaryngology Bozzi Michael Thomas Jefferson Univ-PA Family Medicine Bulat Evgeny NYP Hosp-Weill Cornell Med Ctr-NY Anesthesiology Carreras Tartak Jossie Massachusetts Gen Hosp Emergency Med/BWH-Harvard Chang Joshua U Arkansas COM-Little Rock Dermatology Chao Timothy Thomas Jefferson Univ-PA Pathology Charles Dorothy U Illinois COM-Peoria UPHM Family Medicine Chiou Jacqueline Hosp of the Univ of PA Emergency Medicine Choi John Harbor-UCLA Med Ctr-CA Surgery-Preliminary Choi John U Southern California Interventional Radiology (Integ) Chou Alan Yale-New Haven Hosp-CT Surgery-Preliminary Clanahan Julie Barnes-Jewish Hosp-MO -

First Name Last Name Club Name DIANA HART Balgowlah IAN

First Name Last Name Club Name DIANA HART Balgowlah IAN MCCARRY Balgowlah DIANE MCCARRY Balgowlah MICHAEL MEAD Balgowlah DIANE MEAD Balgowlah LINDY MYERS Balgowlah ROGER SCURR Balgowlah BOBBY ADCOCK Beecroft MARK ANDERSON Beecroft BOB CATHERALL Beecroft LOUISE CATHERALL Beecroft DAVID DART Beecroft MARGARET DART Beecroft LUCIE GABB Beecroft JOHANNA JOHNS Beecroft DAVID SHERWOOD Beecroft CATHY SHERWOOD Beecroft JEFF BANKS Belrose TOM BENNETT Belrose CHRIS BROWNLEE Belrose MIRIAM BROWNLEE Belrose KOS PSALTIS Belrose JOANNE PSALTIS Belrose GLENDA WALSH Belrose ROBYN WOOD Belrose CHRIS WOOD Belrose IAN ARNOLD Berowra TOM BORG Berowra YVONNE BORG Berowra PEGGY SANDERS Berowra LEE BENNETT Blackheath STAN BENNETT Blackheath BOB BURNETT Blackheath JOHN ISBISTER Blackheath ADRIENNE ISBISTER Blackheath EDDIE MCCOY Blackheath EMIL KUNC Brookvale JOHN RE Brookvale MALCOLM LINDQUIST Brownhill Creek, SA ANTOINETTE LINDQUIST Brownhill Creek, SA STEPHEN HUMPHREYS Camden JUDITH HUMPHREYS Camden ANNE ABRAHAM Carlingford ROSS ABRAHAM Carlingford JULES ADAN Carlingford COLIN BOOTH Carlingford LYN BOOTH Carlingford TONY COLACO Carlingford JUDY DAVIDSON Carlingford JOHN DAVIDSON Carlingford GAIL FOX Carlingford BEN FOX Carlingford DOREEN HAMILTON Carlingford GARY HAYMAN Carlingford BOB LAWRANCE Carlingford PAMELA LAWRANCE Carlingford CHRIS LONG Carlingford JON LONG Carlingford RON MILLER Carlingford MOYRA MILLER Carlingford MIKE MORGAN Carlingford CAROL MORGAN Carlingford JAN MORGANS Carlingford JOY POGSON Carlingford NOLA STROM Carlingford ED STROM Carlingford -

1 Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry Witness Statement of Ian BRODIE Support

WIT.003.001.8118 Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry Witness Statement of Ian BRODIE Support person present: No 1. My name is Ian James Brodie. My date of birth is 1950. My contact details are known to the Inquiry. 2. I worked for Quarriers from 1977 to 1985. I was employed as a social worker in Quarriers Village and later combined this with being a fieldwork teacher. Qualifications and work history Qualifications 3. I completed a BA (Hons) in Sociology at the University of Strathclyde in 1974. I obtained a Diploma in Social Work from the University of Edinburgh in 1975, when I became a qualified social worker. 4. I completed a Post-Qualifying Certificate in Social Work Education at Jordanhill College in 1982 and a Masters in Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh in 1990. Work history and training 5. From 1975 to 1977, I worked as an area team social worker with Edinburgh Corporation based in Muirhouse. 6. I worked for Quarriers from 1977 as an in-house social worker. I had responsibility for approximately 70 children based in 5 different cottages and also the adolescent 1 WIT.003.001.8119 hostel. I also did out of hours duties on a rota where the social workers were on call to intervene and resolve possible problems that arose in the cottages. 7. While at Quarriers, I attended several in-service training days such as on life story work. I attended a 5 day training course on "social work skills" run by the National Institute for Social Work Education in Coventry in 1978. -

Jane Gibbs: 'Little Bird That Was Caught

RAMSEY COUNTY Digging Into the Past The Gibbs A Publication o f the Ramsey County Historical Society Claim Shanty Page 17 Spring, 1996 V olum e 3 1, N um ber l Childhood Among the Dakota Jane Gibbs: ‘Little Bird That Was Caught Jane DeBow Gibbs (Zitkadan UsawinJ, an undated portrait by C. A. DeLong, Sunbeam Gallery, St. Anthony, Minnesota, dating from the 1880s. Ramsey County Historical Society archives. See article beginning on page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 31, Number 1 Spring, 1996 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Joanne A. Englund Chairman of the Board John M. Lindley CONTENTS President Laurie Zenner 3 Letters First Vice President Judge Margaret M. Marrinan 4 ‘Little Bird That Was Caught’ and Her Dakota Friends Second Vice President Deanne Zibell Weber Richard A. Wilhoit Secretary James Russell 17 Digging Into the Past: The Excavating of Treasurer The Claim Shanty of Heman and Jane Gibbs Arthur Baumeister, Jr., Alexandra Bjorklund, ThomondR. O’Brien Mary Bigelow McMillan, Andrew Boss, Thomas Boyd, Mark Eisenschenk, Howard Guthmann, John Harens, Marshall Hatfield, 21 Growing Up in St. Paul Liz Johnson, George A. Mairs, Mary Bigelow Sam’s Cash-and-Carry, the Tiger Store— McMillan, Laurie Murphy, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Thomond O’Brien, Robert Olsen, Vicenta Payne Avenue and the 1930s Depression Scarlett, Evangeline Schroeder, Charles Ray Barton Williams, Jr., Anne Cowie Wilson. EDITORIAL BOARD 2 4 Books, Etc. John M. Lindley, chairman; Thomas H. A Painted Herbarium: The Life and Art of Emily Boyd, Thomas C. Buckley, Pat Hart, Laurie M. -

Texas Decertifications Through 2016 Id First Name Middle Name Last

Texas decertifications through 2016 Id First Name Middle Name Last Name Suffix AKA Agency Name Category Effective Date 22798 Esequiel Legarreta Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 4/12/2016 22797 James Watson Kelley Williamson County Sheriff's Office Revocation 4/12/2016 22796 Chandler Lauren K. Lauren Conaway Horton ARLINGTON POLICE DEPT. Revocation 4/12/2016 22775 Brian Odell Burt Lubbock Police Department Revocation 3/21/2016 22774 Robert Dorson Ahrens Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/9/2016 22773 Mark A. Hernandez BEXAR CO. SHERIFF DEPT. Revocation 3/22/2016 22772 Shirl Duane Lawson Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/23/2016 22771 Marvin Eduardo Machado Houston Police Department Revocation 3/9/2016 22770 Ramon Rios Uvalde Police Department Revocation 1/29/2016 22769 Van Melvin Vincent Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/7/2016 22715 Carl Monnerlyn Birdwell Jr. Kerr County Sheriff's Office Revocation 3/16/2016 22714 Brian Corey Caldwell Jr. DALLAS CO. SHERIFFS DEPT. Revocation 3/16/2016 22713 Joshua Zephaniah Owens Travis County Sheriff's Office Revocation 3/16/2016 22712 Stephanie Renee Pointer Stephanie Thomas Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/16/2016 22711 Brandon Lewis Rose Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/16/2016 22710 Jaren Carl Speck Midland Police Department Revocation 3/16/2016 22709 Robert Ashley Williams Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 3/16/2016 22681 Trenton M. Wade Bexar County Sheriff's Office Revocation 7/1/2013 22680 Reuben Joshua Rodriguez El Paso County Sheriff's Office Revocation 9/3/2015 22679 Richard Rene Rivera Texas Department of Public Safety Revocation 11/12/2014 22676 Juan Angel Pruneda Bexar County Sheriff's Office Revocation 2/28/2016 22675 Adam Lamar Brooks Unknown/Unspecified Revocation 2/15/2016 22674 Konrad Chatys San Antonio Police Department Revocation 2/11/2016 22673 Alberto Estrada Jr. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

PR 2305 Comment Letters

February 22, 2021 Ian MacMillan Victor Juan South Coast Air Quality Management District 21865 Copley Drive Diamond Bar, California 91765-4178 Sent Via Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Subject: Comments on Proposed Rule 2305 (Warehouse Indirect Source Rule) Dear Mr. MacMillan: The Long Beach Area Chamber of Commerce officially opposes the adoption of Rule 2305 (Indirect Source Rule). A significant portion of our membership is involved in the support and development of distribution warehouses that are integral to the Southern California logistics industry. The logistics industry plays a crucial role in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic—not only in the distribution of medical supplies, vaccines, and equipment but also in delivering goods to a public that has become increasingly dependent on e-commerce. We believe the District’s proposed ISR is a misguided policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The District is pursuing a regulation targeting a sector that serves as a lifeline to our region and the nation and is deemed essential by federal and state governments. Under the current draft rule, reporting obligations begin only 60 days from rule adoption. The substantive WAIRE Points obligations will commence as soon as July 2021. The Long Beach Area Chamber of Commerce has the following comments in response to the District’s Proposed Rule 2305 (Warehouse Indirect Source Rule): 1. This rule would impose additional/permanent costs on warehouses of approximately $.90 per square foot. This extra cost would amount to targeting a specific essential industry with $1 billion in annual fees during the worst possible time and while responding to the pandemic’s challenges on behalf of our nation. -

Latvia Name Day Calendar

Name Day Calendar “He calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. When he has brought out all his own, he goes on ahead of them, and his sheep follow him because they know his voice.” JOHN 10:3B-4 Name Day Celebration Latvian Style Latvia is one of the few countries in Europe that has the tradition of celebrating Name Days. This unique tradition began as part of the early Christian Church calendar to commemorate the saints and angels. The practice then moved to celebrating the people who were named after a saint. Eventually, other names were added to the calendar to celebrate all people’s names. There are one to five names assigned to each day of the year. The dates and names can’t be interchanged. During Leap Year, February 29 is an open date to celebrate names that are not included in the calendar. Another date reserved as an open date to celebrate names not on the calendar annually is May 22. Name Day is a large part of the culture in Latvia! All the calendars, diaries, and notebooks have the Names printed with the corresponding date. Radio Stations at the beginning of the morning news, broadcast whose name is being celebrated that day. The larger newspapers print the names next to their date of issue for that particular day. It’s like a birthday, but in some ways even better. Your name is mentioned everywhere, even your cell phone providers send you a text greeting. On your Name Day you receive flowers (a standard gift of celebration in Latvia) students and adults alike bring sweets or chocolates to recognize and celebrate.