Criminal Fraud Ellen S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Trafficking and Exploitation

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EXPLOITATION MANUAL FOR TEACHERS Third Edition Recommended by the order of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Armenia as a supplemental material for teachers of secondary educational institutions Authors: Silva Petrosyan, Heghine Khachatryan, Ruzanna Muradyan, Serob Khachatryan, Koryun Nahapetyan Updated by Nune Asatryan The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication has been issued without formal language editing by IOM. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Armenia 14, Petros Adamyan Str. UN House, Yerevan 0010, Armenia Telephone: ¥+374 10¤ 58 56 92, 58 37 86 Facsimile: ¥+374 10¤ 54 33 65 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int/countries/armenia © 2016 International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

Nvcc College-Wide Course Content Summary Lgl 218 - Criminal Law (3 Cr.)

NVCC COLLEGE-WIDE COURSE CONTENT SUMMARY LGL 218 - CRIMINAL LAW (3 CR.) COURSE DESCRIPTION Focuses on major crimes, including their classification, elements of proof, intent, conspiracy, responsibility, parties, and defenses. Emphasizes Virginia law. May include general principles of applicable Constitutional law and criminal procedure. Lecture 3 hours per week. GENERAL COURSE PURPOSE This course is designed to introduce the student to the various substantive and procedural areas of criminal law. ENTRY LEVEL COMPETENCIES Although there are no prerequisites for this course, proficiency (at the high school level) in spoken and written English is recommended for its successful completion. COURSE OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this course, the student should be able to: - describe the structure of the criminal justice system - describe the elements of various federal and Virginia state crimes - understand the ways in which a person can become a party to a crime - describe the elements of various affirmative defenses to federal and Virginia state crimes - understand the basic structure of the law governing arrest, search and seizure, and recognize Constitutional issues posed in these areas - describe the stages of criminal proceedings, in both federal and state courts, and assist a prosecutor or defense lawyer at each stage of such proceedings MAJOR TOPICS TO BE INCLUDED - crimes versus moral wrongs - felonies vs. misdemeanors - criminal capacity - actus reas, mens rea and causation - elements of various federal and Virginia state crimes - inchoate crimes: attempt, solicitation, and conspiracy - parties to a crime - affirmative defenses - insanity - probable cause - arrest, with and without a warrant - search and seizure, with and without a warrant - grand jury indictments - bail and pretrial release - pretrial proceedings - steps of trial and appeal EXTRA TOPICS WHICH MAY BE INCLUDED - purposes of criminal law and punishment - sentencing, probation and parole - special issues posed by mental illness - special issues posed by the death penalty . -

Access to Justice for Children: Mexico

ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR CHILDREN: MEXICO This report was produced by White & Case LLP in November 2013 but may have been subsequently edited by Child Rights International Network (CRIN). CRIN takes full responsibility for any errors or inaccuracies in the report. I. What is the legal status of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)? A. What is the status of the CRC and other relevant ratified international instruments in the national legal system? The CRC was signed by Mexico on 26 January 1990, ratified on 21 November 1990, and published in the Federal Official Gazette (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 25 January 1991. In addition to the CRC, Mexico has ratified the Optional Protocols relating to the involvement of children in armed conflict and the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. All treaties signed by the President of Mexico, with the approval of the Senate, are deemed to constitute the supreme law of Mexico, together with the Constitution and the laws of the Congress of the Union.1 The CRC is therefore part of national law and may serve as a legal basis in any proceedings before the national courts. It is also part of the supreme law of Mexico as a whole and must be implemented at federal level and in all the individual states.2 B. Does the CRC take precedence over national law The CRC has been interpreted to take precedence over national laws, but not the Constitution. According to doctrinal thesis LXXVII/99 of November 1999, international treaties are ranked second immediately after the Constitution and ahead of federal and local laws.3 On several occasions, Mexico’s Supreme Court has stated that international treaties take precedence over national law, mainly in the case of human rights.4 C. -

Guilt, Dangerousness and Liability in the Era of Pre-Crime

Please cite as: Getoš Kalac, A.M. (2020): Guilt, Dangerousness and Liability in the Era of Pre-Crime – the Role of Criminology? Conference Paper presented at the 2019 biannual conference of the Scientific Association of German, Austrian and Swiss Criminologists (KrimG) in Vienna. Forthcoming in: Neue Kriminologische Schriftenreihe der Kriminologischen Gesellschaft e.V., vol. 118, Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg. Guilt, Dangerousness and Liability in the Era of Pre-Crime – the Role of Criminology? To Adapt, or to Die, that is the Question!1 Anna-Maria Getoš Kalac Abstract: There is no doubt that, in terms of criminal policy, we have been living in an era of pre-crime for quite some time now. Whether we like it or not, times have changed and so has the general position on concepts of (criminal) guilt, dangerousness and liability. Whereas once there was a broad consensus that penal repression, at least in principle, should be executed in a strictly post-crime fashion, nowadays same consensus has been reached on trading freedom (from penal repression) for (promised) security, long before an ‘actual crime’ might even be committed. In this regard the criminalisation of endangerment and risks only nomotechnically solves the issue of ‘actual’ vs. ‘potential’ crimes – in essence it merely creates a normative fiction of pre-crime crimes, whereas in reality ‘actual crimes’ do not exist at all. The starting point of criminalisation has clearly shifted away from the guilt of having committed a crime, to the mere dangerousness of potentially committing a crime, which potential as such is purely hypothetical and beyond the grasp of empirical proof. -

The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. V. North Carolina

THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ADOPTS A REASONABLE JUVENILE STANDARD IN J.D.B. V NORTH CAROLINA FOR PURPOSES OF THE MIRANDA CUSTODY ANALYSIS: CAN A MORE REASONED JUSTICE SYSTEM FOR JUVENILES BE FAR BEHIND? Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney∗ I. Introduction II. The Reasonable Person Standard a. Background b. The Reasonable Person Standard and Children: Kids Are Different III. Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida: Embedding Developmental Research Into the Court’s Constitutional Analysis IV. From Miranda v. Arizona to J.D.B. v. North Carolina V. J.D.B. v. North Carolina: The Facts and The Analysis VI. Reasonableness Applied: Justifications, Defenses, and Excuses a. Duress Defenses b. Justified Use of Force c. Provocation d. Negligent Homicide e. Felony Murder VII. Conclusion I. Introduction The “reasonable person” in American law is as familiar to us as an old shoe. We slip it on without thinking; we know its shape, style, color, and size without looking. Beginning with our first-year law school classes in torts and criminal law, we understand that the reasonable person provides a measure of liability and responsibility in our legal system.1 She informs our * ∗Marsha L. Levick is the Deputy Director and Chief Counsel for Juvenile Law Center, a national public interest law firm for children, based in Philadelphia, Pa., which Ms. Levick co-founded in 1975. Ms. Levick is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University School of Law. Elizabeth-Ann “LT” Tierney is the 2011 Sol and Helen Zubrow Fellow in Children's Law at the Juvenile Law Center. -

A Content Analysis of Crimes Posted on Social Media Platforms Abstract I. Introduction

82 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 1 • Spring 2018 A Content Analysis of Crimes Posted on Social Media Platforms Alessandra Brainard Strategic Communications Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract With an increasing rate of violent crimes across the country as well as an uptick in crime in the news, perpetrators have turned to social media to gain attention, posting their crimes online. This study analyzed the motives of individuals who post their crimes on social media. By incorporating Sigmund Freud’s theories on guilt and utilizing a narrative criticism of testimony, the findings demonstrate a lack of remorse and guilt on the part of criminals who conduct unlawful acts, such as drunk driving, gang rape, and murder. The study concluded that the rationale behind committing the crime and posting evidence of the illegal activities on social media outlets stems from the drive of human beings to be recognized by others in their environment and social media communities. I. Introduction Historical Context With a skyrocketing presence of violent crimes across the country as well as an increase in crime in the news, perpetrators are turning to social media to gain attention by posting their crimes on social media platforms. The FBI’s Uniform Crime Report showed an increase in violent crime in 38 out of 50 states in 2016 (FBI, 2016). Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has attempted to raise awareness around this issue, has declared, “The Department of Justice is committed to working with our state, local, and tribal partners across the country to deter violent crime, dismantle criminal organizations and gangs, stop the scourge of drug trafficking, and send a strong message to criminals that we will not surrender our communities to lawlessness and violence” (The United States Department of Justice, 2017). -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

LENS FINAL 12/1/2010 5:47:02 PM Honest Confusion: The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation Jill Wieber Lens∗ I. INTRODUCTION Suppose that a plaintiff is injured in a rear-end collision car accident. Even though the rear-end collision was not a dramatic accident, the plaintiff incurred extensive medical expenses because of a preexisting medical condition. Through a negligence claim, the plaintiff can recover compensatory damages based on his medical expenses. But is it fair that the defendant should be liable for all of the damages? It is not as if he rear-ended the plaintiff on purpose. Maybe the fact that defendant’s conduct was not reprehensible should reduce the amount of damages that the plaintiff recovers. Any first-year torts student knows that the defendant’s argument will not succeed. The defendant’s conduct does not control the amount of the plaintiff’s compensatory damages. The damages are based on the plaintiff’s injury because, in tort law, the purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole by putting him in the same position as if the tort had not occurred.1 But there are tort claims where the amount of compensatory damages is not always based on the plaintiff’s injury. Suppose that a defendant fraudulently misrepresents that a car for sale is brand-new. The plaintiff then offers to purchase the car for $10,000. Had the car actually been new, it would have been worth $15,000, but the car was instead worth only $10,000. As they have for a very long time, the majority of jurisdictions would award the plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages 2 based on the plaintiff’s expected benefit of the bargain. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

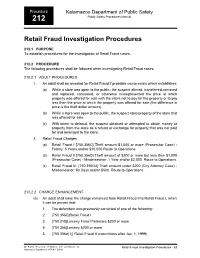

Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures

Procedure Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety Public Safety Procedures Manual 212 Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures 212.1 PURPOSE To establish procedures for the investigation of Retail Fraud cases. 212.2 PROCEDURE The following procedures shall be followed when investigating Retail Fraud cases. 212.2.1 ADULT PROCEDURES 1. An adult shall be arrested for Retail Fraud if probable cause exists which establishes: (a) While a store was open to the public, the suspect altered, transferred, removed and replaced, concealed, or otherwise misrepresented the price at which property was offered for sale with the intent not to pay for the property or to pay less than the price at which the property was offered for sale (the difference in price is the theft dollar amount). (b) While a store was open to the public, the suspect stole property of the store that was offered for sale. (c) With intent to defraud, the suspect obtained or attempted to obtain money or property from the store as a refund or exchange for property that was not paid for and belonged to the store. 2. Retail Fraud Charges (a) Retail Fraud I [750.356C] Theft amount $1,000 or more (Prosecutor Case) - Felony: 5 Years and/or $10,000 Route to Operations. (b) Retail Fraud II [750.356D] Theft amount of $200 or more but less than $1,000 (Prosecutor Case) - Misdemeanor: 1 Year and/or $2,000. Route to Operations. (c) Retail Fraud III- [750.356D4] Theft amount under $200 (City Attorney Case) - Misdemeanor: 93 Days and/or $500. Route to Operations 212.2.2 CHARGE ENHANCEMENT (a) An adult shall have the charge enhanced from Retail Fraud II to Retail Fraud I, when it can be proven that: 1. -

Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 16 Mar 2021 | Jurisdiction: District of Columbia, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-029-0846 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to fraud claims under District of Columbia law. This Q&A addresses the elements of actual fraud, including material misrepresentation and reliance, and other types of fraud claims, such as fraudulent concealment and constructive fraud. Elements Generally – nondisclosure of a material fact when there is a duty to disclose (Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (D.C.) v. Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (Md.), 1. What are the elements of a fraud claim in 223 F. Supp. 3d 1, 10 (D.D.C. 2016) (applying District your jurisdiction? of Columbia law)). To state a claim of common law fraud (or fraud in the (Sundberg v. TTR Realty, LLC, 109 A.3d 1123, 1131 inducement) under District of Columbia law, a plaintiff (D.C. 2015).) must plead that: • A material misrepresentation actionable in fraud • The defendant made: must be consciously false and intended to mislead another (Sarete, Inc. v. 1344 U St. Ltd. P’ship, 871 A.2d – a false statement of material fact (see Material 480, 493 (D.C. 2005)). A literally true statement Misrepresentation); that creates a false impression can be actionable in fraud (Jacobson v. Hofgard, 168 F. Supp. 3d 187, 196 – with knowledge of its falsity; and (D.D.C.