Measuring the Value of Information in Nuval Shelf Nutrition Label Feifei Liang, North Carolina State University Chen Zhen, Unive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition Facts” Label?

ANSWERS Lifestyle + Risk Reduction by heart Diet + Nutrition How Do I Understand the “Nutrition Facts” Label? Most foods in the grocery store have a Nutrition Facts label and ingredient list. When you go grocery shopping, take time to read the Nutrition Facts labels on the foods you purchase. Compare the nutrients and calories in one food to those in another. The information may surprise you. Make sure you aren’t buying foods high in calories, saturated fat, trans fat, sodium and added sugars! What information is on the Nutrition Facts label? The Nutrition Facts label contains this information: • Trans Fat – is also considered a “bad fat” because it • Serving size — tells you how much of the food is can raise your LDL cholesterol and your risk of heart considered a “serving.” A package may contain multiple disease. Choose foods with “0” grams of trans fat. Read servings. Servings per container will tell you the total the ingredient list to avoid foods that contain “partially number of servings in a package or container. If you eat hydrogenated” oils. Everyone can benefit from limiting more or less than the serving size listed, you need to trans fat. do the math to figure out the amount of nutrients and • Cholesterol — is found in foods that come from number of calories you’ve eaten. animals, such as meats, poultry, seafood, eggs and • Calories — tell you how much energy is in the food. It’s full-fat dairy products. The FDA’s Dietary Guidelines important to pay attention to calories if you’re trying to for Americans recommend eating as little dietary lose weight or manage your weight. -

Nutrition Facts and Requiring Mandatory Declaration of AGENCY: Food and Drug Administration, Supplement Facts Labels Added Sugars HHS

33742 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 103 / Friday, May 27, 2016 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND MD 20740, 240–402–5429, email: f. How Total Carbohydrates Appears on the HUMAN SERVICES [email protected]. Label g. Calculation of Calories From SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Food and Drug Administration Carbohydrate Table of Contents 2. Sugars 21 CFR Part 101 a. Definition Executive Summary b. Mandatory Declaration [Docket No. FDA–2012–N–1210] Purpose of the Regulatory Action c. Changing ‘‘Sugars’’ to ‘‘Total Sugars’’ Summary of the Major Provisions of the d. DRV RIN 0910–AF22 Regulatory Action in Question e. Seasonal Variation in Sugars Content Costs and Benefits 3. Added Sugars Food Labeling: Revision of the I. Background a. Declaration Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels A. Legal Authority (i) Comments on the Rationale for B. Need To Update the Nutrition Facts and Requiring Mandatory Declaration of AGENCY: Food and Drug Administration, Supplement Facts Labels Added Sugars HHS. II. Comments to the Proposed Rule and the (ii) Evidence on Added Sugars and Risk of ACTION: Final rule. Supplemental Proposed Rule, Our Chronic Disease Responses, and a Description of the Final (iii) New Evidence Presented in the 2015 SUMMARY: The Food and Drug Rule DGAC Report Administration (FDA or we) is A. Introduction b. The 2015 DGAC Analysis of Dietary amending its labeling regulations for B. General Comments Patterns and Health Outcomes conventional foods and dietary 1. Comments Seeking an Education c. Authority for Labeling supplements to provide updated Campaign or Program (i) Statutory Authority nutrition information on the label to 2. -

Nutrition Labelling Toolkit

Nutrition Labelling Toolkit The Nutrition Facts tables, illustrations and photographs used in this Toolkit are for illustrative purposes only. Nutrient values within the tables do not represent any particular food or product. Any resemblance of the pictures and illustrations to any products is coincidental and does not represent any specific product found in the market place. The Nutrition Labelling Toolkit provides guidance on the interpretation of the nutrition labelling requirements under the Food and Drug Regulations. This guidance document is intended for use by inspectors of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. It may also be used by manufacturers, importers and distributors of food products, and consultants. The information in this document is intended for instructional purposes only and does not in any way override the Food and Drugs Act or the Food and Drug Regulations. Where there is a conflict between the Food and Drugs Act and/or the Food and Drug Regulations and this Toolkit, the Act and/or Regulations will supersede the Toolkit. Table of Contents Note: To assist readers in finding the answers to specific questions, each section begins with an expanded and annotated Table of Contents. Section A Introduction Purpose of the Nutrition Labelling Toolkit ....................................................................................................1 References and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................2 Classes of Food for the Purposes -

Is Rockville Walkable?

Vol 12 Issue 3 May/June 2014 Board Bulletin You may have noticed the office building construction on the corner of Blackwell and Shady Grove Roads that is adjacent to the Fallsgrove Hilton Garden Inn/ Homewood Suites hotels. In less than a year’s time, the once vacant parcel was transformed into one of Rockville’s most dynamic and technological office medi- cal buildings – Fallsgrove Plaza. Devel- oped by Rockville based Lerner, the new five-story flagship office tower opened in March 2014. Is Rockville Walkable? “Walkable” communities are increasingly becoming a measure of a region’s quality of life. As the City of Rockville celebrates Bicycle Awareness Month in May, it is a great time to evaluate what a walkable community means to you. The City is asking you to share your thoughts on its Engage Rockville site, a web- site that helps residents shape the future of Rockville through online dialogues. See the full story on page 7 Continued on page 2 Content & Special Features Board Bulletin . 3 The Grove Gardener . 14 Thomas Farm Events . 4 Real Estate Listings . 16 Is Rockville Walkable? . 7 Spring Maintenance Tips . 17 Addressing Mean Girls . 8 Neighborhood Watch . 19 It’s For Your Health . 10 Rockville News . 20 305 No. Permit Southern MD Southern Rockville MD 20850 MD Rockville Random Acts of Kindess . 12 Board Minutes . 21 PAID 400 Casey Lane Casey 400 U.S. Postage Postage U.S. Jewish Heritage Tour . 13 Word Find . 26 Association Owners Property Fallsgrove The Prsrt Std. Prsrt Visit Your Fallsgrove Community Web Site: www.atFallsgrove.com Address Return 2 • INSIDE FALLSGROVE BOARD OF DIRECTORS BULLETIN that keeps the building cool in the summer and warm Continued from Page 1 in the winter. -

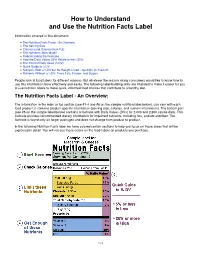

How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label

How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label Information covered in this document: ● The Nutrition Facts Panel - An Overview ● The Serving Size ● Calories (and Calories from Fat) ● The Nutrients: How Much? ● Understanding the Footnote ● How the Daily Values (DV) Relate to the %DVs ● The Percent Daily Value (%DV) ● Quick Guide to %DV ● Nutrients With a %DV but No Weight Listed - Spotlight on Calcium ● Nutrients Without a %DV: Trans Fats, Protein, and Sugars People look at food labels for different reasons. But whatever the reason, many consumers would like to know how to use this information more effectively and easily. The following label-building skills are intended to make it easier for you to use nutrition labels to make quick, informed food choices that contribute to a healthy diet. The Nutrition Facts Label - An Overview: The information in the main or top section (see #1-4 and #6 on the sample nutrition label below), can vary with each food product; it contains product-specific information (serving size, calories, and nutrient information). The bottom part (see #5 on the sample label below) contains a footnote with Daily Values (DVs) for 2,000 and 2,500 calorie diets. This footnote provides recommended dietary information for important nutrients, including fats, sodium and fiber. The footnote is found only on larger packages and does not change from product to product. In the following Nutrition Facts label we have colored certain sections to help you focus on those areas that will be explained in detail. You will not see these colors on the food labels on products you purchase. -

A “Nutrition Label” for Privacy Patrick Gage Kelley,* Joanna Bresee,* Lorrie Faith Cranor,* Robert W

A “Nutrition Label” for Privacy Patrick Gage Kelley,* Joanna Bresee,* Lorrie Faith Cranor,* Robert W. Reeder** * Carnegie Mellon University ** Microsoft School of Computer Science Trust User Experience (TUX) pkelley, jbresee, [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT frequently difficult for consumers to understand. Online privacy We used an iterative design process to develop a privacy label that policies are confusing due to the use of specific terms that many presents to consumers the ways organizations collect, use, and people do not understand, descriptions of activities that people share personal information. Many surveys have shown that have difficulty relating to their own use of websites, a readability consumers are concerned about online privacy, yet current level that is congruent with a college education, and a non- mechanisms to present website privacy policies have not been committal attitude towards specifics [14]. These issues are successful. This research addresses the present gap in the complicated by companies creating policies that are tested by their communication and understanding of privacy policies, by creating lawyers, not their customers. It has further been established an information design that improves the visual presentation and through numerous studies that people do not read privacy policies comprehensibility of privacy policies. Drawing from nutrition, [21] and make mistaken assumptions based upon seeing that a site warning, and energy labeling, as well as from the effort towards has a link to a privacy policy [26]. A recent study estimated that if creating a standardized banking privacy notification, we present consumers were somehow convinced to read the policies of all the our process for constructing and refining a label tuned to privacy. -

The Nutrition Facts Label: Look for It and Use

The Nutrition Facts Label Look for It and Use It! Information Found on Use it to you need food and compare to make beverage and healthy packages choose choices foods! throughout your day Check the serving size and servings % Daily Value (%DV) is the percentage of the Daily Value per container. The nutrition information (reference amounts of nutrients to consume or not to exceed listed on the Nutrition Facts label is each day for adults and children 4 years of age and older) and usually based on one serving of the food. Size up 4 servings per container Use %DV shows how much a nutrient in a serving of the food contributes Servings Serving size 1 1/2 cup (208g) to a total daily diet. Use %DV to see how a food’s nutrients Packages can—and often do— stack up and choose foods that are higher in nutrients to contain more than one serving! Amount per serving get more of and lower in nutrients to get less of. If you eat multiple servings, you’re getting Calories “multiples” on calories and nutrients, too. 240 TIP: 5% DV or less per serving is low and = % Daily Value* 20% DV or more per serving is high 2SERVINGS CALORIES&NUTRIENTSX2 Total Fat 4g 5% Choose Saturated Fat 1.5g 8% Nutrients Trans Fat 0g Nutrients To Nutrients To Calories from food provide the Cholesterol 5mg 2% Wisely energy your body needs to function Sodium 430mg 19% Get More Of Get Less Of and grow. Balance the number of Consider Total Carbohydrate 46g 17% Compare and choose Compare and choose foods to calories you eat and drink with the Dietary Fiber 7g 25% foods to get 100% DV of get less than 100% DV of these the number of calories you burn Total Sugars 4g these on most days: each day: during physical activity. -

Use the Nutrition Facts Label to Eat Healthier

USE THE NUTRITION FACTS Know your fats and reduce sodium for your health. • To help reduce your risk of heart disease, use the LABEL TO EAT HEALTHIER label to select foods that are lowest in saturated fat, trans fat and cholesterol. • Trans fat doesn't have a % DV, but consume as little as Check the serving size and number of servings. possible because it increases your risk of heart disease. • The Nutrition Facts Label information is based on ONE • The % DV for total fat includes all different kinds of fats. serving, but many packages contain more. Look at the • To help lower blood cholesterol, replace saturated and serving size and how many servings you are actually trans fats with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated consuming. If you double the servings you eat, you fats found in fish, nuts, and liquid vegetable oils. double the calories and nutrients, including the % DVs. • Limit sodium to help reduce your risk of high • When you compare calories and nutrients between blood pressure. brands, check to see if the serving size is the same. Reach for healthy, wholesome carbohydrates. Calories count, so pay attention to the amount. • Fiber and sugars are types of carbohydrates. Healthy sources, like fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains, • This is where you’ll find the number of calories per can reduce the risk of heart disease and improve serving and the calories from fat in each serving. digestive functioning. • Fat-free doesn’t mean calorie-free. Lower fat items • Whole grain foods can’t always be identified by color may have as many calories as full-fat versions. -

What's on a Food Label?

HEF619 What’s on a Food Label? Participant Guide Julie A. Albrecht, Extension Food Specialist Food labels help consumers make purchasing decisions and provide information about the product. An attractive label initially helps sell the product to the consumer and gives the consumer information about the product identity, quality, nutrition, and relevant health and safety information. Fig. 01 Fig. 02 Fig. 03 Let’s take a look at a food label to see what information it contains. Net Weight of Contents Statement Five pieces of information are required on all food labels: The edible product in the container is listed by weight, • a statement of identity volume, or numerical count depending on the product. The • a net weight of contents statement weight and volume must be listed in both English and metric units. • an ingredient statement • a statement that gives the name and place of business of the product’s manufacturer, packer, or distributor Ingredients Statement • the Nutrition Facts label The list of ingredients in the product is listed below the Nutrition Facts panel. The ingredients are listed by their com- mon or usual name in descending order by weight. For exam- Statement of Identity ple: If whole grain rolled oats is listed first, that ingredient has This statement describes the product and preferably the the largest amount of weight in the product. The ingredient common name of the food. A unique or fanciful name may be listed last contributes the least amount by weight. Ingredients used if no common name exists as long as the name describes containing an allergen may be listed in the ingredient state- the product so the consumer knows what is in the product. -

Food Labels (PDF)

Lesson 5 Food Labels OBJECTIVES To create awareness of the Nutrition Facts label To learn how to locate different items of information on the label To learn how to compare foods based on information found on the label To make bug boxes and allow the students to collect and identify bugs in their garden APPLICABLE CONTENT STANDARDS English–language arts Mathematics Science (See the matrix in Appendix B.) Materials for In-class Lesson and Materials for Gardening Activity Activities Handouts: 2 tuna fish cans, 6 oz. size—rinsed 5-1 Your Turn—Nutrition Facts Label 12” square screen mesh 5-2 Point Cards (photocopy onto thicker paper; Plaster of paris make enough cards for each student when cut) Water 5-3 Food Label Activity Sheet Small plastic bag (snack-size, self-sealing) 5-4 Comparing Food Labels Insect stickers (optional) Spot the Block Let’s Play a Game Use the Nutrition Facts Label to Eat Healthier Overhead transparency of food label or enlarged copy (see page 86) Loaf of 100% whole wheat bread Foods with labels for activities (see handout 5-3) Masking tape Lesson 5: Food Labels 77 Preparation for In-class Lesson Preparation for Gardening Activity and Activities Day before the lesson: Day before the lesson: Photocopy handouts 5-1, 5-2 (limited copies), 5-3, Gather materials. 5-4, and Spot the Block, Let’s Play a Game, and Prepare wire mesh (see directions under “Garden Use the Nutrition Facts Label to Eat Healthier Activity.”) Cut up point cards. Measure about 1/2 cup of the plaster of paris and Make a transparency of the label or enlarge it 120% place into each of the plastic self-sealing bags. -

Nutrition Facts Format Examples

Examples of Nutrition Facts Panels for Ground Products Beef, ground, 95% lean / 5% fat, raw Nutrition Facts Serving Size 4 oz (112g) raw, as packaged. Servings Per Container varied Amount Per Serving Calories 150 Calories from Fat 50 % Daily Value* Total Fat 6g 9% Saturated Fat 2.5g 13% Cholesterol 70mg 23% Sodium 75mg 3% Total Carbohydrate 0g 0% Protein 24g 48% Iron 15% • Not a significant source of dietary fiber, sugars, vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000- calorie diet Beef, ground, 90% lean / 10% fat, raw Nutrition Facts Serving Size 4 oz (112g) raw, as packaged. Servings Per Container varied Amount Per Serving Calories 200 Calories from Fat 100 % Daily Value* Total Fat 11g 17% Saturated Fat 4.5g 23% Cholesterol 75mg 24% Sodium 75mg 3% Total Carbohydrate 0g 0% Protein 22g 45% Iron 15% • Not a significant source of dietary fiber, sugars, vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000- calorie diet Beef, ground, 80% lean / 20% fat, raw Nutrition Facts Serving Size 4 oz (112g) raw, as packaged. Servings Per Container varied Amount Per Serving Calories 280 Calories from Fat 200 % Daily Value* Total Fat 22g 34% Saturated Fat 9g 43% Cholesterol 80mg 27% Sodium 75mg 3% Total Carbohydrate 0g 0% Protein 19g 38% Iron 10% • Not a significant source of dietary fiber, sugars, vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000- calorie diet Beef, ground, 75% lean / 25% fat, raw Nutrition Facts Serving Size 4 oz (112g) raw, as packaged. -

The Crazy Maze of Food Labeling and Food Claims Laws

St. John's Law Review Volume 92 Number 2 Volume 92, Summer 2018, Number 2 Article 3 The Crazy Maze of Food Labeling and Food Claims Laws Patrick Meyer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CRAZY MAZE OF FOOD LABELING AND FOOD CLAIMS LAWS PATRICK MEYER † INTRODUCTION There is a de facto right in America to know what contents make up the food we consume. 1 The United States Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) regulates food labels and label claims made on meat, poultry, and egg products, 2 and the United States Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) regulates the labeling and labeling claims on all other foods. 3 The mission of the FDA is to protect the health of the public. 4 The FDA has the monumental task of identifying and remedying unsubstantiated product claims. Consider the various teas sold at cancerherbtea.com, which touted their ability to heal cancer and dozens of similar claims as described in a recent FDA Warning Letter. 5 Some of the unsubstantiated claims included: “Cancer Herb Tea ‘You have nothing to lose but your cancer,’ ” “Proven to help kill the cancer cells, try out the natural herbal † Library Director & Associate Professor of Law, University of Detroit Mercy School of Law.