The Evolution of Syncopation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

BOP HARMONY by Contrast with the Earliest Jazz Musicians, Bop Musicians Did More Than Embellish a Song

Jazz Styles Gridley Eleventh Edition Jazz Styles Mark C. Gridley Eleventh Edition ISBN 978-1-29204-259-6 9 781292 042596 ISBN 10: 1-292-04259-1 ISBN 13: 978-1-292-04259-6 Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoned.co.uk © Pearson Education Limited 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affi liation with or endorsement of this book by such owners. ISBN 10: 1-292-04259-1 PEARSON® ISBN 13: 978-1-292-04259-6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Printed in the United States of America Copyright_Pg_7_24.indd 1 7/29/13 11:28 AM uring the 1940s, a number of adventuresome D musicians showed the effects of studying the advanced swing era styles of saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, pianists Art Tatum and Nat Cole, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, guitarist Charlie Christian, and the Count Basie rhythm section. -

The Development of Musical Improvisation in Second Grade Children

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Graduate Research Papers Student Work 2011 The development of musical improvisation in second grade children Akiko Yoshizawa University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2011 Akiko Yoshizawa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Yoshizawa, Akiko, "The development of musical improvisation in second grade children" (2011). Graduate Research Papers. 256. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/256 This Open Access Graduate Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Research Papers by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The development of musical improvisation in second grade children Abstract The purpose of this qualitative case study was to investigate if second-grade children could develop a solo improvisation on an Orff xylophone. Participants were five African-American children who attended a model school that followed an inquiry-based approach curriculum. These children also had a chance to learn music from a faculty and the researcher, who had been exploring constructivist methods of teaching music, with a special emphasis on invented songs, instruments, and notations. The three-day study focused on how children were able to create a solo improvisation. The study was guided by the following questions: (1) Can second grade children develop improvisations on a song they have just learned? (2) What kind of improvisations do they develop? (3) Can second-grade children analyze their own improvisations? If so, how do they describe them? In order to analyze their level of musical complexity, a coding, based on Music Educators National Conference (MENC) K-4 performance standard, was developed to analyze the progression of children's improvisation. -

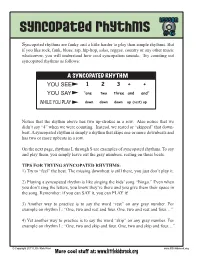

Syncopated Rhythms #6

lesson Syncopated rhythms #6 Syncopated rhythms are funky and a little harder to play than simple rhythms. But if you like rock, funk, blues, rap, hip-hop, salsa, reggae, country or any other music whatsoever, you will understand how cool syncopation sounds. Try counting out syncopated rhythms as follows: A SYNCOPATED RHYTHM YOU SEE 1 2 3 + + YOU SAY “one two three and and” WHILE YOU PLAY down down down up (rest) up Notice that the rhythm above has two up-strokes in a row. Also notice that we didn’t say “4” when we were counting. Instead, we rested or “skipped” that down- beat. A syncopated rhythm is simply a rhythm that skips one or more downbeats and has two or more upbeats in a row. On the next page, rhythms L through S are examples of syncopated rhythms. To say and play them, you simply leave out the gray numbers, resting on those beats. TIPS FOR TRYING SYNCOPATED RHYTHMS: 1) Try to “feel” the beat. The missing downbeat is still there, you just don’t play it. 2) Playing a syncopated rhythm is like singing the kids’ song “Bingo.” Even when you don’t sing the letters, you know they’re there and you give them their space in the song. Remember: if you can SAY it, you can PLAY it! 3) Another way to practice is to say the word “rest” on any gray number. For example on rhythm L: “One, two and rest and four. One, two and rest and four…” 4) Yet another way to practice is to say the word “skip” on any gray number. -

Cadenzas Written for the First Movement Of

Abstract This thesis is an analytical study of various cadenzas written for the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.20 in D minor, K.466. As one of the six of his own concertos for which Mozart did not provide an original cadenza, the D minor concerto poses an important challenge to the performer: should she compose or improvise her own cadenza, or should she select one written by someone else? Many composer/pianists active during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries penned cadenzas to this concerto for their own use, and this thesis explores those by August Eberhard Müller, Emanuel Aloys Förster, Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Charles-Valentin Alkan, Clara Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Ferruccio Busoni, Bedrich Smetana and Paul Badura-Skoda. In addition to these written-out cadenzas, it also discusses improvised cadenzas in the recordings by Robert Levin and Chick Corea. Each composer/pianist’s unique compositional style is illuminated through the study of each cadenza, and consideration of these styles allows multiple views on a single concerto. A discussion of the meaning and history of cadenzas precedes the analytical study, and in conclusion, the author contributes her own cadenza. Acknowledgments Dr. Karim Al-Zand, for your guidance and wonderful insight during my research. Dr. Jon Kimura Parker, for being the endless source of my inspiration, in every way. Dr. Robert Roux and Dr. Richard Lavenda for your continuous support throughout my five years of study at Rice University. And my deepest love and gratitude to my parents, for always believing in me. Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Introduction.......................................................................................................1 I. -

Music – Blues Composition

Sample assessment task Year level 9 Learning area The Arts Subject Music Title of task Blues composition Task details Description of task Students individually compose a melody based on the 12-bar blues. They need to include a suitable piano/keyboard part and a walking bass line, and will be asked to incorporate notes from the corresponding blues scales and syncopation. Compositions need to also include dynamic and expressive devices, such as accents. Students will use a combination of practical and written activities to compose the melody, piano/keyboard part and walking bass line. The final composition may be presented on manuscript or available technologies, such as Sibelius. Type of assessment Formative and summative To inform progression of learning in a unit Purpose of To assess students’ understanding of form, blues scales, syncopation, dynamics assessment and expressive devices at the end of a learning cycle Assessment strategy Written final composition, using conventional notation. Evidence to be Composition task sheet collected Anecdotal notes throughout the process Suggested time Four sessions (240 minutes) Content description Content from the Composing and arranging Western Australian Use and application of composition models to shape and refine arrangements and Curriculum original works; improvising, combining and manipulating the elements of music; applying compositional devices, stylistic features and conventions to reflect a range of music styles Use of a range of invented and conventional notation, appropriate music terminology and available technologies to organise, record and communicate music ideas The specified content listed under the Elements of music for the relevant year level will be integrated throughout 2017/53303 [PDF 2017/42226] The Arts | Music | Year 9 | Making | Blues composition 1 Task preparation Prior learning Students have completed a range of aural, theoretical, analytical and practical activities exploring blues tonality and scale structure. -

Syncopation and the Score. Song, C; Simpson, AJ; Harte, CA; Pearce, MT; Sandler, MB

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Syncopation and the score. Song, C; Simpson, AJ; Harte, CA; Pearce, MT; Sandler, MB © 2013 Song et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/10967 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Syncopation and the Score Chunyang Song*, Andrew J. R. Simpson, Christopher A. Harte, Marcus T. Pearce, Mark B. Sandler Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom Abstract The score is a symbolic encoding that describes a piece of music, written according to the conventions of music theory, which must be rendered as sound (e.g., by a performer) before it may be perceived as music by the listener. In this paper we provide a step towards unifying music theory with music perception in terms of the relationship between notated rhythm (i.e., the score) and perceived syncopation. In our experiments we evaluated this relationship by manipulating the score, rendering it as sound and eliciting subjective judgments of syncopation. We used a metronome to provide explicit cues to the prevailing rhythmic structure (as defined in the time signature). -

I a COMPARATIVE STUDY of the JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES of CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, and FREDDIE HUBBARD an EXAMINATION of IMPROVISA

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE FROM 1953-1964 by JAMES HARRISON MOORE Bachelor of Music, West Virginia University, 2003 Master of Music, University of the Arts, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by James Harrison Moore It was defended on March 29, 2012 Committee Members: Dean L. Root, Professor, Music Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Music Lawrence Glasco, Professor, History Dissertation Advisor: Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music ii Copyright © by James Harrison Moore 2012 iii Nathan T. Davis, PhD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD: AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYE FROM 1953-1964. James Harrison Moore, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study is a comparative examination of the musical lives and improvisational styles of jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown, and two prominent jazz trumpeters whom historians assert were influenced by Brown—Donald Byrd and Freddie Hubbard. Though Brown died in 1956 at the age of 25, the reverence among the jazz community for his improvisational style was so great that generations of modern jazz trumpeters were affected by his playing. It is widely said that Brown remains one of the most influential modern jazz trumpeters of all time. In the case of Donald Byrd, exposure to Brown’s style was significant, but the extent to which Brown’s playing was foundational or transformative has not been examined. -

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER TWO: “AFTER THE BALL”: POPULAR MUSIC OF THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES Chapter Outline I. Minstrelsy A. The minstrel show 1. The first form of musical and theatrical entertainment to be regarded by European audiences as distinctively American in character 2. Featured mainly white performers who artificially blackened their skin and carried out parodies of African American music, dance, dress, and dialect 3. Emerged from rough-and-tumble, predominantly working-class neighborhoods such as New York City’s Seventh Ward, commercial urban zones where interracial interaction was common 4. Early blackface performers were the first expression of a distinctively American popular culture. B. George Washington Dixon 1. The first white performer to establish a wide reputation as a “blackface” entertainer 2. Made his New York debut in 1828 3. His act featured two of the earliest “Ethiopian” songs, “Long Tail Blue” and “Coal Black Rose.” CHAPTER TWO: “AFTER THE BALL”: POPULAR MUSIC OF THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES a) Simple melodies from European tradition C. Thomas Dartmouth Rice (1808–60) 1. White actor born into a poor family in New York’s Seventh Ward 2. Demonstrated the potential popularity and profitability of minstrelsy with the song “Jim Crow” (1829), which became the first international American song hit 3. Sang this song in blackface while imitating a dance step called the “cakewalk,” an Africanized version of the European quadrille (a kind of square dance) 4. The cakewalk was developed by slaves as a parody of the “refined” dance movements of the white slave owners. a) The rhythms of the music used to accompany the cakewalk exemplify the principle of syncopation. -

Creative Musical Improvisation in the Development and Formation of Nexus Percussion Ensemble

! ! CREATIVE MUSICAL IMPROVISATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND FORMATION OF NEXUS PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE ! ! ! ! Olman Eduardo! Piedra ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements !for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL! ARTS May !2014 Committee: Roger B. Schupp, Advisor Gregory A. Rich, Graduate Faculty Representative Katherine L. Meizel John W. Sampen !ii ABSTRACT ! Roger B. Schupp, Advisor ! ! The percussion ensemble is a vital contemporary chamber group that has lead to a substantial body of commissions and premieres of works by many prominent composers of new music. On Saturday May 22nd, 1971, in a concert at Kilbourn Hall at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, NEXUS percussion ensemble, hailed by many as the world’s premiere percussion ensemble, improvised the entire program of their inaugural, 120 minute concert as a newly formed group, while using non-Western instruments with which the majority of the audience were unfamiliar.! NEXUS percussion ensemble has been influential in helping create new sounds and repertoire since their formation in 1971. While some scholarly study has focused on new commission for the medium, little attention has been given to the importance and influence of creative improvised music (not jazz) in the formation of NEXUS and its role in the continued success of the contemporary percussion ensemble.! This study examined the musical and cultural backgrounds of past and current members of NEXUS percussion ensemble, and the musical traditions they represent and recreate. The author conducted and transcribed telephone interviews with members of NEXUS percussion ensemble, examined scholarly research related to drumming traditions of the world and their use of improvisation, researched writings on creative improvisation and its methods, and synthesized !iii the findings of this research into a document that chronicles the presence of creative improvisation in the performance practices of NEXUS percussion ensemble.