25 the Producer-Unit System: Management by Specialization After 1931

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Marie: I Don't Love You Ron Smith, Thompson Rivers University, Canada

Rose Marie: I Don't Love You Ron Smith, Thompson Rivers University, Canada Pierre Berton, in his book Hollywood's Canada, challenges the Hollywood image of Canada, particularly the Canadian frontier. Berton states: And if Canadians continue to hold the belief that there is no such thing as a national identity – and who can deny that many hold it? – it is because the movies have frequently blurred, distorted, and hidden that identity under a celluloid mountain of misconceptions. (Berton, 1975: 12) Berton's queries about film images seem to suggest that without a clear understanding of history, we might be subject to the dreams and imaginations of others. In Berton's case, "the others" are Hollywood producers and directors. Geoff Pevere and Greig Dymond state that Americans have made many more Mountie movies than Canadians have, noting that "the inadvertent or intentional kitsch value of these is almost always rooted in the image of the Mountie's impossible purity or sense of duty." (Pevere and Dymond, 1996: 183) Michael Dawson, in That Nice Red Coat Goes To My Head Like Champagne: Gender, Antimodernism and the Mountie Image, points out that "Mounted Policemen appeared as central characters in over 250 feature films." (Dawson, 1997) Pierre Berton notes that by the early 1920s Hollywood had made 188 Mountie movies, forty-eight of them in the feature length mode that had become popular after 1914 (Berton, 1975: 112). Dawson adds that by the 1930s and 1940s "the film industry produced a body of work that consolidated the fictional Mountie position as both a mythic hero and commercial success." (Dawson, 1997) Rose Marie (1936) continued a theme that was associated with love and duty, but which had very little to do with "true story claims" about the Mounted Police. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

National Box Office Digest Annual (1940)

Ho# Ujjfice JbiaeAt Haui: «m JL HE MOST IMPORTANT NEWS of many moons to this industry is the matter-of-fact announcement by Technicolor that it will put into effect a flat reduction of one cent a foot on release prints processed after August 1st. "There is a great industrial story of days and nights and months and years behind the manner in which Dr. Kalmus and his associates have boosted the quality and service of color to the industry, beaten down the price step by step, and maintained a great spirit of cooperation with production and exhibition. TECHNICOLOR MOTION PICTURE CORPORATION HERBERT T. KALMUS, President , 617 North La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, Subscription Rate, $10.00 Per ■Ml ^Ite. DIGEST ANNUAL *7lie. 1/ea>i WcM. D OMESTIC box office standings take on values in this year of vanished foreign markets that are tremendous in importance. They are the only ratings that mean anything to the producer, director, player, and exhibitor. Gone—at least for years to come—are the days when known box office failures in the American market could be pushed to fabulous income heights and foisted on the suffering American exhibitor because of a shadowy "for¬ eign value.” Gone are the days—and we hope forever—when producers could know¬ ingly, and with "malice aforethought,” set out on the production of top budgetted pictures that would admittedly have no appeal to American mass audiences, earn no dimes for American exhibitors. All because of that same shadowy foreign market. ^ ^ So THE DIGEST ANNUAL comes to you at an opportune time. -

Early Spring 2017

Early Spring SPECIAL EVENTS Wednesday, March 22 – Sunday, March 26 Friday, April 14 – Sunday, April 16 (Visit brattlefilm.org for ticket prices and more info) The Nineteenth Repertory Series! BOSTON UNDERGROUND FILM FESTIVAL Cambridge Science Festival: Sunday, February 26 2017: The 17th Annual Boston’s premiere festival highlighting the bizarre, the troubling, and the CONTACT! Friday, February 24 – overlooked returns to the Brattle for their nineteenth year. We are thrilled to In celebration of this year’s Cambridge Science Festival, the Brattle is BRATTLE OSCAR PARTY! welcome back these purveyors of the weird and wondrous, and eagerly pleased to present a brief program of films in which the aliens actually do Save the date for the Brattle’s annual celebration of Hollywood’s biggest Monday, May 1, 2017 await their full line-up. ‘come in peace.’ It’s easy to be overwhelmed by blockbuster sci-fi flicks fea - night! Come join us for snacks and drinks as we cheer our favorites during Keep watching BOSTONUNDERGROUND.ORG for more details but, in the turing bombastic scenes of world landmarks being blown to bits by aggres - “the movie-lover’s Super Bowl.” Visit Brattlefilm.org/oscar for more infor - meantime, we can announce the following features: HIDDEN RESERVES, THE sive E.T.’s – but let’s not forget those times when the visitors have been enig - mation on how to attend. SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS & PREMIERES VOID and A DARK SONG. No Brattle Passes accepted. matic messengers, curious explorers, or even fun-loving stoners. Please join us for some fun from the stars with this survey of (relatively) benign aliens. -

John Garfield

John Garfield: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Garfield, John, 1913-1952 Title: John Garfield Papers Dates: 1932-2010, undated Extent: 4 document boxes, 2 oversize box (osb), 2 bound volumes (bv) (5.04 linear feet) Abstract: The John Garfield papers, 1932-2010, consist of production photographs and film stills, headshots, photographs, posters, sheet music, clippings, and press releases from his film and stage work; film contracts, articles, magazines, family photos, and correspondence donated by his daughter, Julie Garfield. Call Number: Film Collection No. FI-00074 Language: English Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Special Handling Special Handling Instructions: Most of the binders in this collection Instructions: have been left in an unaltered or minimally processed state to provide the reader with the look and feel of the original. When handling the binders with inserted materials, users are asked to be extremely careful in retaining the original order of the material . Most of the photographs and negatives in the collection have been sleeved, but patrons must use gloves when handling unsleeved photographic materials. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. -

Presentation #4- Opening

1 PRESENTATION #4- OPENING Good afternoon fellow club members and friends. Today we hope to enlighten you in regards to two aspects of Nelson’s and Jeanette’s lives. The first is in regard to clarifying that the love that existed between these two people was real. To accomplish this we will report actual private and sensitive quotations from both parties and you can draw your own conclusions as to the validity of their love. Most are not from their early romance days when they might be expected, but after their love had been ongoing for years. This was a life-long love between these two passionate human beings. The tragedy of living in an era of Victorian attitudes took a toll. It is a shame that in this age where their private life would be accepted as perfectly normal, there are those who still insist on judging it by Victorian morals and refute their love with salacious terms as “adulterous”! That term disappeared from our vocabulary back in the sixties! Their love was so powerful that they had to live two lives, public and private. We are going to take just a brief look at their private life and take a modern and tolerant position of what they had to overcome but not give up the love they had for one another. Any woman today would feel as Jeanette did if they could just experience a little of the love she received. And no doubt there are modern men today that would be overwhelmed to be as confident as Nelson was in the love he received from his Jeanette. -

The Companion Film to the EDITED by Website, Womenfilmeditors.Princeton.Edu)

THE FULL LIST OF ALL CLIPS in the film “Edited By” VERSION #2, total running time 1:53:00 (the companion film to the EDITED BY website, WomenFilmEditors.princeton.edu) 1 THE IRON HORSE (1924) Edited by Hettie Gray Baker Directed by John Ford 2 OLD IRONSIDES 1926 Edited by Dorothy Arzner Directed by James Cruze 3 THE FALL OF THE ROMANOV DYNASTY (PADENIE DINASTII ROMANOVYKH) (1927) Edited by Esfir Shub Directed by Esfir Shub 4 MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (CHELOVEK S KINO-APPARATOM) (1929) Edited by Yelizaveta Svilova Directed by Dziga Vertov 5 CLEOPATRA (1934) Edited by Anne Bauchens Directed by Cecil B. De Mille 6 CAMILLE (1936) Edited by Margaret Booth Directed by George Cukor 7 ALEXANDER NEVSKY (ALEKSANDR NEVSKIY) (1938) Edited by Esfir Tobak Directed by Sergei M. Eisenstein and Dmitriy Vasilev 8 RULES OF THE GAME (LA RÈGLE DU JEU) (1939) Edited by Marguerite Renoir Directed by Jean Renoir 9 THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939) Edited by Blanche Sewell Directed by Victor Fleming 10 MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (1943) Edited by Maya Deren Directed by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid 11 IT’S UP TO YOU! (1943) Edited by Elizabeth Wheeler Directed by Henwar Rodakiewicz 12 LIFEBOAT (1944) Edited by Dorothy Spencer Directed by Alfred Hitchcock 13 ROME, OPEN CITY (ROMA CITTÀ APERTA) (1945) Edited by Jolanda Benvenuti Directed by Roberto Rossellini 14 ENAMORADA (1946) Edited by Gloria Schoemann Directed by Emilio Fernández 15 THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI (1947) Edited by Viola Lawrence Directed by Orson Welles 16 LOUISIANA STORY (1948) Edited by Helen van Dongen Directed by Robert Flaherty 17 ALL ABOUT EVE (1950) Edited by Barbara “Bobbie” McLean Directed by Joseph L. -

The Transom Review February, 2003 Vol

the transom review February, 2003 Vol. 3/Issue 1 Edited by Sydney Lewis Gwen Macsai’s Topic About Gwen Macsai Gwen Macsai is an award winning writer and radio producer for National Public Radio. Her essays have been heard on All Things Considered, Morning Edition and Weekend Edition Saturday with Scott Simon since 1988. Macsai is also the creator of "What About Joan," starring Joan Cusack and author of "Lipshtick," a book of humorous first person essays published by HarperCollins in February of 2000. Born and bred in Chicago (south shore, Evanston), Macsai began her career at WBEZ-FM and then moved to Radio Smithsonian at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. After working for NPR for eight years she moved to Minneapolis, MN where "Lipshtick" was born, along with the first of her three children. Then, one day as she tried to wrangle her smallish-breast-turned-gigantic- snaking-fire-hose into the mouth of her newborn babe, James L. Brooks, (Producer of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, The Simpsons and writer of Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News and As Good As It Gets), called. He had just heard one of her essays on Morning Edition and wanted to base a sitcom on her work. In 2000, "What About Joan" premiered. The National Organization for Women chose "What About Joan" as one of the top television shows of that season, based on its non- sexist depiction and empowerment of women. Macsai graduated from the University of Illinois and lives in Evanston with her husband and three children. Copyright 2003 Atlantic Public Media Transom Review – Vol. -

Writing for Instructional Television. P INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 221 158 IR 010 181 AUTHOR O'Bry,an, Kenneth G. no. TITLE Writing for Instructional Television. P INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-89776-0521-2 PUB DATE' 81 NOTE 157p. AVAILABLE FROM-Corporation for Public Broadcasting, 1111 16th St.," N.W., Washington, DC 20036 ($5.0,0, prepaid). EDRS PRICE MF01 Plds Postage. PC Not Available from' EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Television; Group Dynamics; *Instructional Design; *Production Techniques; *Programing (Broadcast); Public Television; *Scripts; Telexiision Studios ABSTRACT Writing Considerations specific to instructional television (ITV) situations are discussed in this handbook written for the beginner, but designed to be of use to anyone creating an ITV script. Advice included in the handbook is based on information obtained from ITV wirters, literature reviews, and the author's ' personal,experience. The ITV writer's relationship to other members of a project team is discussed, as well as the role of each team member, including the project leader, instructional designer, academic consultant, researcher, producer/director, utilization - person, and writer. Specific suggestions are then made for writing and working with the project team and additional production crew members. A chapter is devoted to such specific ITV writing conventions as script format, production grammar, camera terminology, and transitions between shots. Understanding production technology is the focus of a chapter which discusses lighting, sound, set design, and special effects. An in-depth look at choice of form--narrative, dramatic, documentary, magazine, ortdrama--is provided, followed by advice and guidelines for dealing with such factors as the target audience, budget and caktitig, treatment, visualization, and revisions. -

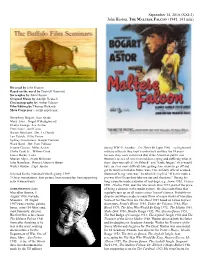

John Huston, the MALTESE FALCON (1941, 101 Min)

September 14, 2010 (XXI:3) John Huston, THE MALTESE FALCON (1941, 101 min) Directed by John Huston Based on the novel by Dashiell Hammett Screenplay by John Huston Original Music by Adolph Deutsch Cinematography by Arthur Edeson Film Editing by Thomas Richards Meta Carpenter....script supervisor Humphrey Bogart...Sam Spade Mary Astor...Brigid O'Shaughnessy Gladys George...Iva Archer Peter Lorre...Joel Cairo Barton MacLane...Det. Lt. Dundy Lee Patrick...Effie Perine Sydney Greenstreet...Kasper Gutman Ward Bond...Det. Tom Polhaus Jerome Cowan...Miles Archer during WW II. Another – Let There Be Light 1946 – so frightened Elisha Cook Jr....Wilmer Cook military officials they kept it under lock and key for 34 years James Burke...Luke because they were convinced that if the American public saw Murray Alper...Frank Richman Huston’s scenes of American soldiers crying and suffering what in John Hamilton...District Attorney Bryan those days was called “shellshock” and “battle fatigue” they would Walter Huston...Capt. Jacobi have an even more difficult time getting Americans to go off and get themselves killed in future wars. One military official accused Selected for the National Film Registry, 1989 Huston of being “anti-war,” to which he replied, “If I ever make a 3 Oscar nominations: best picture, best screenplay, best supporting pro-war film I hope they take me out and shoot me.” During his actor (Greenstreet) long career he made a number of real dogs, e.g. Annie 1982, Victory 1981, Phobia 1980, and The Macintosh Man 1973, part of the price JOHN HUSTON (John of being a director in the studio system. -

Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences

AMPAS FUBlICATIONS Acadilmyof Motion (, ""'.". /I.~ts and I::"" ... ~ .:",-!. L~Jr~ ry I -_._' >..'- --'>,,'-;- C;:;h----t. APRIL BULLETIN ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS & SCIENCES EXECUTIVE OFFICES AND LOUNGE: ROOSEVELT HOTEL,7010 HOLLYWOOD BLVD. TEL. GR-2134 No. XX HOLLYWOOD. CALIF.• APRIL 8. 1929 No. XX JUDGING ACADEMY ' BY THE RECORD The Academy will celebrate the second anniver Other types of criticisms have been captious, sary of its foundation by a dinner the night of May thoughtless or even malicious in their inspiration, 16, the first and chief feature being the formal be marked by distortions of facts and frequently by stowal of Merit Awards for distinguished achieve outright misstatements. Obviously, the Academy of ments of 1928. Particulars of the dinner will be Motion Picture Arts and Sciences cannot descend to found elsewhere in this issue of the Bulletin. the absurdity of a personal controversy with any With the near approach of the second anniversary dubious assailant of this character. The answers, if of the Academy's organization it is timely to report any should ever be required, will again be found in to the Academy membership on behalf of the officers the Academy's actual achievements. and Board of Directors the exact progress that has The aims and purposes of the Academy may be been made in carrying out the purposes for which again summarized as follows: the Academy was founded. How substantial this 1. Promotion of harmonious and equitable rela progress has been will be judged by the record rather tions within the production industry. than by laudatory superlatives on one hand or cap '2.