The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Origins and Ends of Existence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES

RESPONDING TO FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES: This sequence of 4 lessons is intended to give learners the opportunity to: • listen attentively to spoken poetry • develop and express their personal response to the meaning of a poem by Dylan Thomas, through spoken/written/creative media • respond to the sound and visual effects within a well-known work of literature • make connections between literature and their own experiences • build their confidence in responding to a complex text • develop skills of close reading, making use of their understanding of stylistic devices to create different effects • imitate and interpret the poem in different media. This unit of 4 lessons covers the following framework objectives: SPEAKING • select, analyse and present ideas and information convincingly or objectively • present topics and ideas coherently, using techniques effectively, e.g. a clear structure, anecdote to illustrate, plausible conclusions • respond to others’ views positively and appropriately when challenged READING • use a range of strategies, e.g. speed reading, close reading, annotation, prediction, to skim texts for gist, key ideas and themes, and scan for detailed information • use their knowledge of: - word roots and families - grammar, sentence and whole-text structure - content and context to make sense of words, sentences and whole texts • read with concentration texts, on-screen and on paper, that are new to them, and understand the information in them • use inference and deduction to understand layers of meaning WRITING -

Alexis Krahling Ms. Gelso Brit Lit 3 March 14, 2014 How Does the Poem “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” Relate To

Krahling)2) ) Alexis Krahling Ms. Gelso Brit Lit 3 March 14, 2014 How does the poem “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” relate to John Keats background and biography? The background of a person’s discuses a person’s past life and the experiences they went through. The biography of a person’s life is the story of a real person’s life written by someone other than that specific person. In “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” by John Keats, published in 1848, parts of Keats background and biography are seen. Keats’s poem was written during the literary time period of Romanticism. Romanticism was a time when writers emphasized feeling and when individual experiences were highly valued. Keats expresses his feelings and his individual experiences in life in “When I Have fears That I May Cease to Be.” In the poem, Keats expresses his fear of dying before he accomplishes his goals and before he sees a specific woman again. He talks about how he feels alone in the world and how love and fame have no value. Knowing about John Keats’s life helps one understand the poem “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” because it relates to John Keats’s background and biography by expressing his fears of death, his past experiences with death, and Keats’s ambitious attitude. John Keats was a well-known British author who wrote poems, like “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be”, during the Romantic Period. -

Dylan Thomas: “A Refusal” to Be a Poet of Love, Pity and Peace

ISSN 2664-4002 (Print) & ISSN 2664-6714 (Online) South Asian Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: South Asian Res J Human Soc Sci | Volume-1 | Issue-3| Oct-Nov -2019 | DOI: 10.36346/SARJHSS.2019.v01i03.016 Original Research Article Dylan Thomas: “A Refusal” to be a Poet of Love, Pity and Peace S. Bharadwaj* Professor of English (Former), Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu 608002, India *Corresponding Author S. Bharadwaj Article History Received: 01.11.2019 Accepted: 10.11.2019 Published: 20.11.2019 Abstract: Dylan Thomas‘s poem ―A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London‖ focuses on the problem of the allotted role of the war time poet involved in choice-making. The agonizing tension, the climate of the global war and the creative fear and anxieties continue to harass the poets of the thirties and the war poets of the forties. One may readily agree with the view that in stylistic maturity the poem surpasses anything Thomas has written before, and it is also true that, at the formal level, the early poem 18 Poems sets the pattern for this later poem. Literary critics interpret the poem within the perspective of death and religion. However the poem, dramatizing the socio-politico-historical functioning of the war poets of the forties and the more ironic complex attitude of Auden and the pitiless attitude of the lost poets of the thirties, brings out the inadequacy of the poet‘s power of comprehension and the pain inherent in human perception. -

Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DYLAN THOMAS READING HIS POETRY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dylan Thomas | none | 02 Aug 2005 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007179459 | English | London, United Kingdom Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry PDF Book Listening to him read his poems taught me so much about poetry! Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. In My Craft or Sullen Art. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. Within each stanza Thomas recounts times in his life when he was in his youth in this particular spot and the joy and pleasure he felt. Region: Wales. Dylan Thomas. The Wales which had offered him such inspiration, but from which he had also, at times, felt the need to escape, finally claimed him. The structure of the poem is a classic villanelle , a line poem of fixed form consisting of five tercets and a final quatrain on two rhymes, with the first and third lines of the first tercet repeated alternately as a refrain closing the succeeding stanzas and joined as the final couplet of the quatrain. Although Thomas was primarily a poet, he also published short stories, film scripts, publicly performed his works and conducted radio broadcasts. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until In contrast though, Thomas hailed from a fairly middle-class background and had grown up with more rural experiences. In the land of the hearthstone tales, and spelled asleep,. -

Fern Hill It, Manipulate It, Transport It

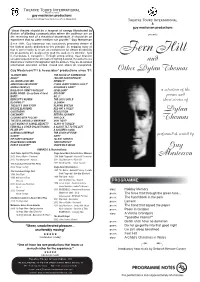

Theatre Tours International incorporating guy masterson pro duc tions Patrons: Melvyn Bragg, Robert Hardy, Peter O’Toole, Maggie Smith Theatre Tours International & guy masterson productions “Great theatre should be a tempest of energy illuminated by flashes of blinding communication where the audience are on presents the receiving end of a theatrical thunderbolt. it should be an experience that no other medium can provide.” Guy Masterson Since 1991, Guy Masterson has consistently presented theatre of the highest quality dedicated to this principle. By stripping away all that is unnecessary to create an environment for vibrant theatricality his productions are designed to grab the audience’s attention, hold Fern Hill it, manipulate it, transport it. Through strong writing, clear direction exceptional performance, atmospheric lighting & sound, the audience are drawn into a ‘contract of imagination’ with the artiste/s. They are illuminated and entertained, educated, excited, moved and, above all, transported. Guy Masterson/TTI & Associates* productions since '91: Other Dylan Th o mas 12 ANGRY MEN THE HOUSE OF CORRECTION ADOLF* I KISSED DASH RIPROCK* ALL WORDS FOR SEX INTIMACY* AMERICANA ABSURDUM* IT WAS HENRY FONDA’S FAULT* ANIMAL FARM (x3) KRISHNAN’S DAIRY* BALLAD OF JIMMY COSTELLO* LEVELLAND* a selection of the BARB JUNGR - Every Grain of Sand MOSCOW* BARE* NO. 2* poems and BERKOFF’S WOMEN THE ODD COUPLE short stories of BLOWING IT* OLEANNA THE BOY’S OWN STORY PLAYING BURTON BYE BYE BLACKBIRD RED HAT & TALES* CASTRADIVA RESOLUTION Dylan -

Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas's Fern Hill and William Wordsworth's Ode: Intimations of Immortality

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 50 (2016) 106-116 EISSN 2392-2192 Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas’s Fern Hill and William Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality Ensieh Shabanirad1,a, Elham Omrani2,b 1Ph.D. Candidate of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2M. A. Student of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran a,bE-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) is one of the greatest twentieth century poets, who composed poetry in English. His passionate emotions and his personal, lyrical writing style make him be alike the Romantic poets than the poets of his era. Much of Thomas’s works were influenced by his early experiences and contacts with the natural world, especially his famous poem, Fern Hill. This paper aims to compare Thomas’s Fern Hill with Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality to illustrate the poets’ different attitudes towards time and childhood. In Fern Hill, Thomas’s attitude towards childhood changes from one of happiness and satisfaction to grief and loss of innocence and carefreeness. Thomas believes that Time seems like a hero to a child and allows him to be innocent and carefree; but as the child grows older and loses his childhood, he considers Time as a villain who imprisons him and does not let him enjoy life anymore and robes his childhood’s blessings and treasures. Conversely, Wordsworth in his Ode: Intimations of Immortality expressed his belief that although Time has taken his childhood creativity and imagination, but matured his thought and reason and given him insight and experience in exchange. -

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 )

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 ) Dylan Marlais Thomas was born on October 27, 1914, in Swansea, South Wales. His father was an English Literature professor. From his early childhood ,Thomas showed love for the rhythmic ballads of Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. B. Yeats, and Edgar Allan Poe. After he dropped out of school at sixteen, he worked as a junior reporter which he soon left to concentrate on his poetry full-time. As a teenager, Thomas wrote more than half of his collected poems. He left for London when he was twenty and there he won the Poet's Corner book prize, and published his first book in 1934, 18 Poems to great acclaim. His other works include: Twenty-Five Poems (1936), The Map of Love (1939), The World I Breath (1939), New Poems (1943), Deaths and Entrances (1946), In Country Sleep, And Other Poems (1952). His Poetical Style There are many features that distinguish Dylan Thomas’s Poetry: 1. Lyricism: Thomas was different from other modernist poets such as Eliot and Auden in that he was not concerned with discussing social, political or intellectual themes. Instead, he was more interested in intense lyricism and highly charged emotion, had more in common with the Romantic tradition. 2. His Imagery: Thomas talks about his poetic imagery in that he makes one image and charges that image with emotion. After that, he would add to the image intellectual and critical or philosophical powers in the hope that this image would produce another image that contradicts the first until he creates many images that conflict with each other. -

M.B. Mclatchey S P a Photography by Mark Andrew James Terry Floridastatepoetsassociation.Org

May | June 2021 VOL. 48.3 F M.B. McLatchey S P A Photography by Mark Andrew James Terry FloridaStatePoetsAssociation.org F S P A EXECUTIVE OFFICERS INSIDE THIS ISSUE President: Mary Marcelle • From The President’s Desk 1 Vice President: Mark Andrew James Terry • M.B. McLatchey 3-14 Secretary: Sonja Jean Craig • Poems Near the Sea 16-37 Treasurer: Robyn Weinbaum • Dylan Thomas 38-42 APPOINTED OFFICERS • Zoomies 43-44 • Member Spotlight 46-48 Anthology Editors: Gary Broughman, Elaine Person, JC Kato Contest Chair: Marc Davidson • FSPA Contest Commitee Report 49-52 Membership Chair: TBD • Awards 53-54 Newsletter Editor: Mark Andrew James Terry • Chapter News & Updates 55-61 with Diane Neff and Mary Marcelle • Editor’s Choice Poetry Challenge 62 Historian: Elaine Person • News, Book Releases & Reviews 63 National Poetry Day/Month Chair: TBD • OPAP Submission Information 64 Youth Chair and Student Contest Chair: TBD • Cadence 2020 is Here! 65 Slam Coordinator: Kevin Campbell Social Media Chair: TBD • A Little Lagniappe 66 Webmaster: Mark Andrew James Terry • Twelve Chairs Short Course 67 Silvia Curbelo’s Newest Release “Silvia Curbelo’s poetry is accomplished, daring, full of energy and intelligence; it is the generous manifestation of an authentic and original gift.” ~ W. S. Merwin “With a knack for disguising wisdom as plain-spoken observation, Curbelo’s poems are infused with insight the way sunlight fills a quiet room. The lyric voice is rarely this accessible, this unwavering, this pure.” ~ Campbell McGrath BUY NOW: http://www.anhingapress.org/silvia-curbelo Available from Anhinga Press • www.anhingapress.com F Florida State Poets Association S An affiliate of the National Federation of State Poetry Societies P A FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK Florida Spring is here, and I am loving the heat without the unbear- able humidity that comes in summer. -

Dylan Thomas - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Dylan Thomas - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Dylan Thomas(27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) Dylan Marlais Thomas was a Welsh poet and writer who wrote exclusively in English. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories and scripts for film and radio, which he often performed himself. His public readings, particularly in America, won him great acclaim; his sonorous voice with a subtle Welsh lilt became almost as famous as his works. His best-known works include the "play for voices" Under Milk Wood and the celebrated villanelle for his dying father, "Do not go gentle into that good night". Appreciative critics have also noted the craftsmanship and compression of poems such as "In my Craft or Sullen Art", and the rhapsodic lyricism in "And death shall have no dominion" and "Fern Hill". <b>Early Life</b> Dylan Thomas was born in the Uplands area of Swansea, Glamorgan, Wales, on 27 October 1914 just a few months after the Thomas family had bought the house. Uplands was, and still is, one of the more affluent areas of the city. His father, David John ('DJ') Thomas (1876–1952), had attained a first-class honours degree in English at University College, Aberystwyth, and was dissatisfied with his position at the local grammar school as an English master who taught English literature. His mother, Florence Hannah Thomas (née Williams) (1882–1958), was a seamstress born in Swansea. Nancy, Thomas's sister, (Nancy Marles 1906–1953) was nine years older than he. Their father brought up both children to speak only English, even though he and his wife were both bilingual in English and Welsh. -

“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas

Name: __________________________________ Class: ________________________________ “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” By Dylan Thomas Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) was a Welsh poet famous for several of his works, including “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” (1952). Thomas was popular during his own time; his use of imagery and rhythm in poetry made his poetry widely accessible. As you read, try to decipher the message of this poem. Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Dylan Thomas’ Boat House in Laugharne Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieve it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. © 1952 Dylan Thomas. Reprinted with permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Text-Based Questions: Directions: Answer the following questions in complete sentences. -

Stellar and Terrestrial Imagery in Dylan Thomas's Poetry

1044 GAUN JSS Apotheosis of Mortal Man: Stellar and Terrestrial Imagery in Dylan Thomas’s Poetry Ölümlü İnsanın Tanrısallaştırılması: Dylan Thomas Şiirinde Yıldız ve Yeryüzü İmgeleri Fahri ÖZ1 Ankara University Abstract Dylan Thomas’s poetry is replete with the images of life and death and their cyclicality and rebirth. Such images include stars that stand for human beings’ potential to reach godly heights on the one hand, and the grass that symbolizes their mortality on the other. Such images appear most prominently in his elegies “After the Funeral”, “And death shall have no dominion”, “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “Fern Hill”, which harbours pastoral elements. The images in these poems can be treated as a strong sign of his interest in paganism. The analysis of such images can provide us with clues about the elucidation of Thomas’s marginal yet indispensible place within English poetry since these images attest to the fact that he was not only influenced by English Romantic poets like John Keats but also Nineteenth-century American poets like Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. Key Words: Apotheosis, Rebirth, Paganism, Stars, Earth, Elegy, Pastoral, Tradition Öz Dylan Thomas’ın şiirleri yaşam-ölüm çevrimselliğini ve yeniden doğuşu imleyen imgeler açısından zengindir. Bu imgeler arasında insanın ölümlü varoluşunu gösteren çimenler olduğu kadar onun tanrısal bir konuma erişebilme gizilgücünü simgeleyen yıldızlar da yer alır. Söz konusu imgeler ağıt türüne dâhil edilebilecek“After the Funeral”, “And death shall have no dominion”, “Do not go gentle into that good night” ve pastoral ögeler içeren“Fern Hill” adlı şiirlerinde öne çıkmaktadır. -

John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas

GWASG PRIFYSGOL CYMRU UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas How to Cite: Kurt Heinzelman, ‘John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas’, International Journal of Welsh Writing in English, 5 (2018), 1, DOI: 10.16995/ijwwe.5.5 Published: April 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of the International Journal of Welsh Writing in English, which is a journal of the University of Wales Press. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). This article is freely available to read but, for reasons of third-party content inclusion, is not openly licensed. Open Access: International Journal of Welsh Writing in English is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The University of Wales Press wishes to acknowledge the funding received from the Open Library of Humanities towards the cost of producing this open access journal. Heinzelman.indd 1 26/04/2018 09:03 Heinzelman.indd 2 26/04/2018 09:03 JOHN BERRYMAN AND THE AMERICAN LEGACY OF DYLAN THOMAS1 Kurt Heinzelman, The University of Texas at Austin Abstract Lost in the celebration of the 2014 Dylan Thomas centenary was why Thomas’s reputation, at least among literary historians and particularly fellow poets, had declined so much in the nearly sixty years since his death. That those poets once influenced by Thomas – and they were legion – produced a kind of ‘Dylan Effect’, diluting what was once impressive is one thesis of this article, even as non- professional readers continue to this day to revere some of his work.