Double-Consciousness in the Work of Dylan Thomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED for THE

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE WEST END TRANSFER OF HOME, I’M DARLING As rehearsals begin, casting is announced for the West End transfer of the National Theatre and Theatr Clwyd’s critically acclaimed co-production of Home, I’m Darling, a new play by Laura Wade, directed by Theatre Clwyd Artistic Director Tamara Harvey, featuring Katherine Parkinson, which begins performances at the Duke of York’s Theatre on 26 January. Katherine Parkinson (The IT Crowd, Humans) reprises her acclaimed role as Judy, in Laura Wade’s fizzing comedy about one woman’s quest to be the perfect 1950’s housewife. She is joined by Sara Gregory as Alex and Richard Harrington as Johnny (for the West End run, with tour casting for the role of Johnny to be announced), reprising the roles they played at Theatr Clwyd and the National Theatre in 2018. Charlie Allen, Susan Brown (Sylvia), Ellie Burrow, Siubhan Harrison (Fran), Jane MacFarlane and Hywel Morgan (Marcus) complete the cast. Home, I’m Darling will play at the Duke of York’s Theatre until 13 April 2019, with a press night on Tuesday 5 February. The production will then tour to the Theatre Royal Bath, and The Lowry, Salford, before returning to Theatr Clwyd following a sold out run in July 2018. Home, I’m Darling is co-produced in the West End and on tour with Fiery Angel. How happily married are the happily married? Every couple needs a little fantasy to keep their marriage sparkling. But behind the gingham curtains, things start to unravel, and being a domestic goddess is not as easy as it seems. -

FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES

RESPONDING TO FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES: This sequence of 4 lessons is intended to give learners the opportunity to: • listen attentively to spoken poetry • develop and express their personal response to the meaning of a poem by Dylan Thomas, through spoken/written/creative media • respond to the sound and visual effects within a well-known work of literature • make connections between literature and their own experiences • build their confidence in responding to a complex text • develop skills of close reading, making use of their understanding of stylistic devices to create different effects • imitate and interpret the poem in different media. This unit of 4 lessons covers the following framework objectives: SPEAKING • select, analyse and present ideas and information convincingly or objectively • present topics and ideas coherently, using techniques effectively, e.g. a clear structure, anecdote to illustrate, plausible conclusions • respond to others’ views positively and appropriately when challenged READING • use a range of strategies, e.g. speed reading, close reading, annotation, prediction, to skim texts for gist, key ideas and themes, and scan for detailed information • use their knowledge of: - word roots and families - grammar, sentence and whole-text structure - content and context to make sense of words, sentences and whole texts • read with concentration texts, on-screen and on paper, that are new to them, and understand the information in them • use inference and deduction to understand layers of meaning WRITING -

Dylan Thomas Resources

Dylan Thomas was born on the 27th October Cwmdonkin Avenue is located in a position that 1914 at 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, a semi-detached is high above Swansea Bay. As young boy Dylan house in the Uplands area of Swansea. would have looked out on the sea every day. 1914 was a momentous year for the World The changing moods of this wide, curving seascape because of the outbreak of the Great War. would have a lasting impact on the imagination of the poet to be. His father was an English teacher and although both his parents could speak Welsh, he and his Dylan would continue to live and work for much sister Nancy were brought up as English speakers. of his life in locations with magnificent sea views. WG22992 © Hawlfraint y Goron / Crown Copyright 2014 / Crown WG22992 © Hawlfraint y Goron www.cadw.wales.gov.uk/learning At Swansea Waterfront a statue of Dylan as a young boy sits looking out over the docks and Although Dylan Thomas did not write in Welsh, at the people who stroll by. The sculptor John the inspiration for much of his work was rooted in Doubleday has shown the poet perched on the the closeness he felt for Wales, its people and its edge of his chair. He looks like he has been caught landscape. The historic town of Laugharne, with its in the moment of creative thought. magnificent castle and its swirling estuary provided him with many creative writing opportunities. He Dylan began to write at a young age. He was a wrote ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog’ from teenager when he began to keep the notebooks the gazebo that is set into the imposing walls of into which he poured his writing ideas, especially the Castle. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Lisa Mansell Cardiff, Wales Mav 2007

FORM OF FIX: TRANSATLANTIC SONORITY IN THE MINORITY Lisa Mansell Cardiff, Wales Mav 2007 UMI Number: U584943 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584943 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 For 25 centuries Western knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that the world is not for beholding. It is for hearing [...]. Now we must learn to judge a society by its noise. (Jacques Attali} DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature fof any degree. Signed r?rrr?rr..>......................................... (candidate) Date STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree o f ....................... (insert MCh, Mfo MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) (candidate) D ateSigned .. (candidate) DateSigned STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources aite acknowledged by explicit references. Signed ... ..................................... (candidate) Date ... V .T ../.^ . STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DYLAN THOMAS READING HIS POETRY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dylan Thomas | none | 02 Aug 2005 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007179459 | English | London, United Kingdom Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry PDF Book Listening to him read his poems taught me so much about poetry! Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. In My Craft or Sullen Art. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. Within each stanza Thomas recounts times in his life when he was in his youth in this particular spot and the joy and pleasure he felt. Region: Wales. Dylan Thomas. The Wales which had offered him such inspiration, but from which he had also, at times, felt the need to escape, finally claimed him. The structure of the poem is a classic villanelle , a line poem of fixed form consisting of five tercets and a final quatrain on two rhymes, with the first and third lines of the first tercet repeated alternately as a refrain closing the succeeding stanzas and joined as the final couplet of the quatrain. Although Thomas was primarily a poet, he also published short stories, film scripts, publicly performed his works and conducted radio broadcasts. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until In contrast though, Thomas hailed from a fairly middle-class background and had grown up with more rural experiences. In the land of the hearthstone tales, and spelled asleep,. -

Fern Hill It, Manipulate It, Transport It

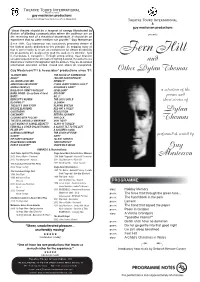

Theatre Tours International incorporating guy masterson pro duc tions Patrons: Melvyn Bragg, Robert Hardy, Peter O’Toole, Maggie Smith Theatre Tours International & guy masterson productions “Great theatre should be a tempest of energy illuminated by flashes of blinding communication where the audience are on presents the receiving end of a theatrical thunderbolt. it should be an experience that no other medium can provide.” Guy Masterson Since 1991, Guy Masterson has consistently presented theatre of the highest quality dedicated to this principle. By stripping away all that is unnecessary to create an environment for vibrant theatricality his productions are designed to grab the audience’s attention, hold Fern Hill it, manipulate it, transport it. Through strong writing, clear direction exceptional performance, atmospheric lighting & sound, the audience are drawn into a ‘contract of imagination’ with the artiste/s. They are illuminated and entertained, educated, excited, moved and, above all, transported. Guy Masterson/TTI & Associates* productions since '91: Other Dylan Th o mas 12 ANGRY MEN THE HOUSE OF CORRECTION ADOLF* I KISSED DASH RIPROCK* ALL WORDS FOR SEX INTIMACY* AMERICANA ABSURDUM* IT WAS HENRY FONDA’S FAULT* ANIMAL FARM (x3) KRISHNAN’S DAIRY* BALLAD OF JIMMY COSTELLO* LEVELLAND* a selection of the BARB JUNGR - Every Grain of Sand MOSCOW* BARE* NO. 2* poems and BERKOFF’S WOMEN THE ODD COUPLE short stories of BLOWING IT* OLEANNA THE BOY’S OWN STORY PLAYING BURTON BYE BYE BLACKBIRD RED HAT & TALES* CASTRADIVA RESOLUTION Dylan -

Swansea Tourist Information Centre (01792 468321 *[email protected] Open All Year Other Tics / Visitor Centres

Attractions coveroutside2014:Layout 1 04/03/2014 14:14 Page 1 Finding Out Swansea Tourist Information Centre (01792 468321 *[email protected] Open all year Other TICs / Visitor Centres Image Credits and Copyrights Mumbles & Gower Mountain Biker p9: Cognation, Rhossili (01792 361302 Nat Trust p11: NTPL/John Millar, Blue *[email protected] Plaque p14: 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, Glynn Open all year Vivian Art Gallery p22: Powell Dobson Architects, Penllergare Valley Woods p29: National Trust Visitor Centre Richard Hanson, Walkers at Three Cliffs Coastguard Cottages, Rhossili, Gower, Bay p33: Visit Wales © Crown Copyright Swansea SA3 1PR (01792 390707 The Council of the City & County of Swansea cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information in this brochure and accepts no Useful Contacts responsibility for any error or misrepresentation, liability for loss, disappointment, negligence or other damage Swansea Mobility Hire caused by the reliance on the information Swansea City Bus Station, contained in this brochure unless caused by Plymouth St, the negligent act or omission of the Council. Swansea SA1 3AR Please check and confirm all details before (01792 461785 booking or travelling. Coastguard This publication is available in (01792 366534 alternative formats. Contact Swansea Tourist Information Published by the City & County of Centre (01792 468321. Swansea © Copyright 2014 A&A cover2014 inside:Layout 1 04/03/2014 14:10 Page 1 Swansea Bay Mumbles, Gower, Afan and The Vale of Neath Scale Key to beach awards 0 6 km Blue Flag and Seaside Award Seaside Award 0 3 miles This map is based on digital photography licensed from NRSC Ltd. -

The Uncanny and Unhomely in the Poetry of RS T

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY '[A] shifting/identity never your own' : the uncanny and unhomely in the poetry of R.S. Thomas Dafydd, Fflur Award date: 2004 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 "[A] shifting / identity never your own": the uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas by Fflur Dafydd In fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The University of Wales English Department University of Wales, Bangor 2004 l'W DIDEFNYDDIO YN Y LLYFRGELL YN UNIG TO BE CONSULTED IN THE LIBRARY ONLY Abstract "[A] shifting / identity never your own:" The uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas. The main aim of this thesis is to consider R.S. Thomas's struggle with identity during the early years of his career, primarily from birth up until his move to the parish of Aberdaron in 1967. -

Eisteddfod Handout Prepared for Ninth Welsh Weekend for Everyone by Marilyn Schrader

Eisteddfod handout prepared for Ninth Welsh Weekend for Everyone by Marilyn Schrader An eisteddfod is a Welsh festival of literature, music and performance. The tradition of such a meeting of Welsh artists dates back to at least the 12th century, when a festival of poetry and music was held by Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth at his court in Cardigan in 1176 but, with the decline of the bardic tradition, it fell into abeyance. The present-day format owes much to an eighteenth-century revival arising out of a number of informal eisteddfodau. The date of the first eisteddfod is a matter of much debate among scholars, but boards for the judging of poetry definitely existed in Wales from at least as early as the twelfth century, and it is likely that the ancient Celtic bards had formalized ways of judging poetry as well. The first eisteddfod can be traced back to 1176, under the auspices of Lord Rhys, at his castle in Cardigan. There he held a grand gathering to which were invited poets and musicians from all over the country. A chair at the Lord's table was awarded to the best poet and musician, a tradition that prevails in the modern day National Eisteddfod. The earliest large-scale eisteddfod that can be proven beyond all doubt to have taken place, however, was the Carmarthen Eisteddfod, which took place in 1451. The next recorded large-scale eisteddfod was held in Caerwys in 1568. The prizes awarded were a miniature silver chair to the successful poet, a little silver crwth to the winning fiddler, a silver tongue to the best singer, and a tiny silver harp to the best harpist. -

Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas's Fern Hill and William Wordsworth's Ode: Intimations of Immortality

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 50 (2016) 106-116 EISSN 2392-2192 Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas’s Fern Hill and William Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality Ensieh Shabanirad1,a, Elham Omrani2,b 1Ph.D. Candidate of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2M. A. Student of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran a,bE-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) is one of the greatest twentieth century poets, who composed poetry in English. His passionate emotions and his personal, lyrical writing style make him be alike the Romantic poets than the poets of his era. Much of Thomas’s works were influenced by his early experiences and contacts with the natural world, especially his famous poem, Fern Hill. This paper aims to compare Thomas’s Fern Hill with Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality to illustrate the poets’ different attitudes towards time and childhood. In Fern Hill, Thomas’s attitude towards childhood changes from one of happiness and satisfaction to grief and loss of innocence and carefreeness. Thomas believes that Time seems like a hero to a child and allows him to be innocent and carefree; but as the child grows older and loses his childhood, he considers Time as a villain who imprisons him and does not let him enjoy life anymore and robes his childhood’s blessings and treasures. Conversely, Wordsworth in his Ode: Intimations of Immortality expressed his belief that although Time has taken his childhood creativity and imagination, but matured his thought and reason and given him insight and experience in exchange. -

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 )

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 ) Dylan Marlais Thomas was born on October 27, 1914, in Swansea, South Wales. His father was an English Literature professor. From his early childhood ,Thomas showed love for the rhythmic ballads of Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. B. Yeats, and Edgar Allan Poe. After he dropped out of school at sixteen, he worked as a junior reporter which he soon left to concentrate on his poetry full-time. As a teenager, Thomas wrote more than half of his collected poems. He left for London when he was twenty and there he won the Poet's Corner book prize, and published his first book in 1934, 18 Poems to great acclaim. His other works include: Twenty-Five Poems (1936), The Map of Love (1939), The World I Breath (1939), New Poems (1943), Deaths and Entrances (1946), In Country Sleep, And Other Poems (1952). His Poetical Style There are many features that distinguish Dylan Thomas’s Poetry: 1. Lyricism: Thomas was different from other modernist poets such as Eliot and Auden in that he was not concerned with discussing social, political or intellectual themes. Instead, he was more interested in intense lyricism and highly charged emotion, had more in common with the Romantic tradition. 2. His Imagery: Thomas talks about his poetic imagery in that he makes one image and charges that image with emotion. After that, he would add to the image intellectual and critical or philosophical powers in the hope that this image would produce another image that contradicts the first until he creates many images that conflict with each other.