Dylan Thomas and Nostalgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Jones Symphonies Nos

Daniel Jones Symphonies Nos. 3 & 5 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra conducted by Bryden Thomson ‘The process of writing any piece of music really is one of discovery and the feeling I always have is that what I’m setting myself to write already exists and that what I have Also Available by Daniel Jones Symphonies on Lyrita to do is unveil it, discover it’.1 This characterisation by Daniel Jones of the creative process as one of exploration and excavation seems appropriate for a composer whose Symphony No. 1 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra, Bryden Thomson scores have a powerful sense of rightness and inevitability. His lifelong dedication to Symphony No. 10 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra, Bryden Thomson.………………..SRCD358 music meant that he was unwilling to compromise by diluting it with other work, such as teaching. When he was mischievously accused of never having had a proper job, his Symphony No. 2 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra, Bryden Thomson Symphony No. 11 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra, Bryden Thomson…..…..…………SRCD364 response was to tap his manuscript and reply, ‘This is a proper job’.2 Born in Pembroke, South Wales, on 7 December 1912, he was brought up in Swansea Symphony No. 4 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Sir Charles Groves Symphony No. 7 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Sir Charles Groves where he lived for most of his life, describing it as ‘that magnet city’.3 His mother was Symphony No. 8 BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra, Bryden Thomson.………………….SRCD329 a singer and his father, Jenkin Jones, was an amateur composer who wrote religious and choral pieces. The young Daniel soon began to compose and by the time he was nine Symphony No. -

FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES

RESPONDING TO FERN HILL by DYLAN THOMAS OBJECTIVES: This sequence of 4 lessons is intended to give learners the opportunity to: • listen attentively to spoken poetry • develop and express their personal response to the meaning of a poem by Dylan Thomas, through spoken/written/creative media • respond to the sound and visual effects within a well-known work of literature • make connections between literature and their own experiences • build their confidence in responding to a complex text • develop skills of close reading, making use of their understanding of stylistic devices to create different effects • imitate and interpret the poem in different media. This unit of 4 lessons covers the following framework objectives: SPEAKING • select, analyse and present ideas and information convincingly or objectively • present topics and ideas coherently, using techniques effectively, e.g. a clear structure, anecdote to illustrate, plausible conclusions • respond to others’ views positively and appropriately when challenged READING • use a range of strategies, e.g. speed reading, close reading, annotation, prediction, to skim texts for gist, key ideas and themes, and scan for detailed information • use their knowledge of: - word roots and families - grammar, sentence and whole-text structure - content and context to make sense of words, sentences and whole texts • read with concentration texts, on-screen and on paper, that are new to them, and understand the information in them • use inference and deduction to understand layers of meaning WRITING -

Papers of Dylan Thomas and Veronica Sibthorp, (NLW MS 21698E.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Papers of Dylan Thomas and Veronica Sibthorp, (NLW MS 21698E.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 13, 2017 Printed: May 13, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/papers-of-dylan-thomas-and-veronica- sibthorp archives.library .wales/index.php/papers-of-dylan-thomas-and-veronica-sibthorp Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Papers of Dylan Thomas and Veronica Sibthorp, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 5 - Tudalen | Page 2 - NLW MS 21698E. Papers of Dylan Thomas and Veronica Sibthorp, Gwybodaeth -

Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DYLAN THOMAS READING HIS POETRY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dylan Thomas | none | 02 Aug 2005 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007179459 | English | London, United Kingdom Dylan Thomas Reading His Poetry PDF Book Listening to him read his poems taught me so much about poetry! Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. In My Craft or Sullen Art. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. Within each stanza Thomas recounts times in his life when he was in his youth in this particular spot and the joy and pleasure he felt. Region: Wales. Dylan Thomas. The Wales which had offered him such inspiration, but from which he had also, at times, felt the need to escape, finally claimed him. The structure of the poem is a classic villanelle , a line poem of fixed form consisting of five tercets and a final quatrain on two rhymes, with the first and third lines of the first tercet repeated alternately as a refrain closing the succeeding stanzas and joined as the final couplet of the quatrain. Although Thomas was primarily a poet, he also published short stories, film scripts, publicly performed his works and conducted radio broadcasts. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until In contrast though, Thomas hailed from a fairly middle-class background and had grown up with more rural experiences. In the land of the hearthstone tales, and spelled asleep,. -

Fern Hill It, Manipulate It, Transport It

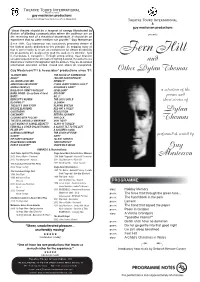

Theatre Tours International incorporating guy masterson pro duc tions Patrons: Melvyn Bragg, Robert Hardy, Peter O’Toole, Maggie Smith Theatre Tours International & guy masterson productions “Great theatre should be a tempest of energy illuminated by flashes of blinding communication where the audience are on presents the receiving end of a theatrical thunderbolt. it should be an experience that no other medium can provide.” Guy Masterson Since 1991, Guy Masterson has consistently presented theatre of the highest quality dedicated to this principle. By stripping away all that is unnecessary to create an environment for vibrant theatricality his productions are designed to grab the audience’s attention, hold Fern Hill it, manipulate it, transport it. Through strong writing, clear direction exceptional performance, atmospheric lighting & sound, the audience are drawn into a ‘contract of imagination’ with the artiste/s. They are illuminated and entertained, educated, excited, moved and, above all, transported. Guy Masterson/TTI & Associates* productions since '91: Other Dylan Th o mas 12 ANGRY MEN THE HOUSE OF CORRECTION ADOLF* I KISSED DASH RIPROCK* ALL WORDS FOR SEX INTIMACY* AMERICANA ABSURDUM* IT WAS HENRY FONDA’S FAULT* ANIMAL FARM (x3) KRISHNAN’S DAIRY* BALLAD OF JIMMY COSTELLO* LEVELLAND* a selection of the BARB JUNGR - Every Grain of Sand MOSCOW* BARE* NO. 2* poems and BERKOFF’S WOMEN THE ODD COUPLE short stories of BLOWING IT* OLEANNA THE BOY’S OWN STORY PLAYING BURTON BYE BYE BLACKBIRD RED HAT & TALES* CASTRADIVA RESOLUTION Dylan -

Jeff Towns (Dylan Thomas) Collection, (GB 0210 DYLTJT)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Jeff Towns (Dylan Thomas) Collection, (GB 0210 DYLTJT) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/jeff-towns-dylan-thomas-collection-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/jeff-towns-dylan-thomas-collection-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Jeff Towns (Dylan Thomas) Collection, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 5 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas's Fern Hill and William Wordsworth's Ode: Intimations of Immortality

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 50 (2016) 106-116 EISSN 2392-2192 Passage of Time and Loss of Childhood in Dylan Thomas’s Fern Hill and William Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality Ensieh Shabanirad1,a, Elham Omrani2,b 1Ph.D. Candidate of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2M. A. Student of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran a,bE-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) is one of the greatest twentieth century poets, who composed poetry in English. His passionate emotions and his personal, lyrical writing style make him be alike the Romantic poets than the poets of his era. Much of Thomas’s works were influenced by his early experiences and contacts with the natural world, especially his famous poem, Fern Hill. This paper aims to compare Thomas’s Fern Hill with Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality to illustrate the poets’ different attitudes towards time and childhood. In Fern Hill, Thomas’s attitude towards childhood changes from one of happiness and satisfaction to grief and loss of innocence and carefreeness. Thomas believes that Time seems like a hero to a child and allows him to be innocent and carefree; but as the child grows older and loses his childhood, he considers Time as a villain who imprisons him and does not let him enjoy life anymore and robes his childhood’s blessings and treasures. Conversely, Wordsworth in his Ode: Intimations of Immortality expressed his belief that although Time has taken his childhood creativity and imagination, but matured his thought and reason and given him insight and experience in exchange. -

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 )

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953 ) Dylan Marlais Thomas was born on October 27, 1914, in Swansea, South Wales. His father was an English Literature professor. From his early childhood ,Thomas showed love for the rhythmic ballads of Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. B. Yeats, and Edgar Allan Poe. After he dropped out of school at sixteen, he worked as a junior reporter which he soon left to concentrate on his poetry full-time. As a teenager, Thomas wrote more than half of his collected poems. He left for London when he was twenty and there he won the Poet's Corner book prize, and published his first book in 1934, 18 Poems to great acclaim. His other works include: Twenty-Five Poems (1936), The Map of Love (1939), The World I Breath (1939), New Poems (1943), Deaths and Entrances (1946), In Country Sleep, And Other Poems (1952). His Poetical Style There are many features that distinguish Dylan Thomas’s Poetry: 1. Lyricism: Thomas was different from other modernist poets such as Eliot and Auden in that he was not concerned with discussing social, political or intellectual themes. Instead, he was more interested in intense lyricism and highly charged emotion, had more in common with the Romantic tradition. 2. His Imagery: Thomas talks about his poetic imagery in that he makes one image and charges that image with emotion. After that, he would add to the image intellectual and critical or philosophical powers in the hope that this image would produce another image that contradicts the first until he creates many images that conflict with each other. -

Dylan Thomas Letters (NLW MS 24037D)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Dylan Thomas letters (NLW MS 24037D) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 09, 2017 Printed: May 09, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/dylan-thomas-letters-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/dylan-thomas-letters-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Dylan Thomas letters Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 6 Gyflwr ffisegol | Physical condition -

John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas

GWASG PRIFYSGOL CYMRU UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas How to Cite: Kurt Heinzelman, ‘John Berryman and the American Legacy of Dylan Thomas’, International Journal of Welsh Writing in English, 5 (2018), 1, DOI: 10.16995/ijwwe.5.5 Published: April 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of the International Journal of Welsh Writing in English, which is a journal of the University of Wales Press. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). This article is freely available to read but, for reasons of third-party content inclusion, is not openly licensed. Open Access: International Journal of Welsh Writing in English is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The University of Wales Press wishes to acknowledge the funding received from the Open Library of Humanities towards the cost of producing this open access journal. Heinzelman.indd 1 26/04/2018 09:03 Heinzelman.indd 2 26/04/2018 09:03 JOHN BERRYMAN AND THE AMERICAN LEGACY OF DYLAN THOMAS1 Kurt Heinzelman, The University of Texas at Austin Abstract Lost in the celebration of the 2014 Dylan Thomas centenary was why Thomas’s reputation, at least among literary historians and particularly fellow poets, had declined so much in the nearly sixty years since his death. That those poets once influenced by Thomas – and they were legion – produced a kind of ‘Dylan Effect’, diluting what was once impressive is one thesis of this article, even as non- professional readers continue to this day to revere some of his work. -

A Study of Dylan Thomas's Poetry

IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSRJHSS) ISSN: 2279-0845 Volume 1, Issue 2 (Sep-Oct. 2012), PP 06-10 www.iosrjournals.org A Study of Dylan Thomas’s Poetry Ch.Nagaraju1, K. V. Seshaiah2 Asst. Prof., Dept of Science and Humanities, N.B.K.R.I.S.T. Vidyanagar, S.P.S.R. Nellore, A.P., India Asst. Prof., Department of Science and Humanities, YITS, Tirupathi, Chittoor, A.P., India Abstract: Dylan Thomas is one of the writers who has often been associated with Welsh literature and culture in the last sixty years. He is possibly the most notable Welsh author. Fortunately, it is mainly his literary work, and not his tumultuous lifestyle, that is still associated with him. The analysis of some of his poems mirrors his sincere relationship to Wales. In 1937 he married to Caitlin MacNamara who gave birth to three children. These circumstances indicate a typical British conservative and straight forward approach to family life. Dylan Thomas was influenced in his writing by the Romantic Movement for the beginning of the nineteenth century and this can be seen in a number of his best works. Dylan Thomas uses symbols and images of nature to express how he feels towards death and childhood. He says that images are used to create a feeling of love towards life. Despite Dylan Thomas’s obscure images, he expresses a clear message of religious devotion in many of his poems. The style of Dylan Thomas is an opaque poetic style which Thomas used to perfection. He possessed tremendous talent and was blessed with immense gifts that made him a professional success at a relatively young age. -

January 2021

Over to YOU A Magazine to keep us connected in these difficult times Welcome to If— The flower for January is Galanthus you can keep your head (Snowdrop) because it’s the earliest when all about you flower to bloom giving cheer on even Are losing theirs and the darkest days. blaming it on you; A promise of better things to come. If you can trust yourself In the very earliest Roman calendars, there were no when all men doubt you, months of January or February at all. The ancient But make allowance for Romans had only ten months and the new year their doubting too; started on March 1st. Ten was a very important If you can wait and not be tired by waiting, Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies, number to them. Even when January or Januarius as Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating, they called it, was added, the New Year continued And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise. to start in March. It remained so in Britain and her If you can dream—and not make dreams your colonies until we switched from the Julian Calendar master; to the Gregorian Calendar in 1752. If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim; Why doesn’t the Tax Year start in January? If you can meet with triumph and disaster Lady Day (March 25th) was one of the quarterly days And treat those two impostors just the same; when rents were traditionally due. Taxes were also due If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken on this day.