Captains of the Soul Michael Evans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

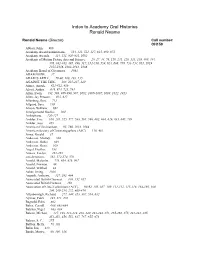

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

Read PDF < Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame

JCHB9GRXNYCN < eBook # Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography Straigh t from th e Horses Mouth : Ronald Neame, an A utobiograph y Filesize: 1.17 MB Reviews This is actually the finest pdf i have got study right up until now. It can be full of wisdom and knowledge Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Reese Morissette II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA R8BUZZDIPL8R // Doc Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography STRAIGHT FROM THE HORSES MOUTH: RONALD NEAME, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Scarecrow Press. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 328 pages. Dimensions: 8.5in. x 5.5in. x 0.9in.Now in Paperback! Ronald Neames autobiography takes its title from one of his best-loved films, The Horses Mouth (1958), starring Alec Guinness. In an informative and entertaining style, Neame discusses the making of that film, along with several others, including In Which We Serve, Blithe Spirit, Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, Tunes of Glory, I Could Go on Singing, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Scrooge, The Poseidon Adventure, and Hopscotch. Straight from the Horses Mouth provides a fascinating, first-hand account of a unique filmmaker, who began his career as assistant cameraman on Hitchcocks first talkie, Blackmail, and went on to direct Maggie Smith, Judy Garland, Walter Matthau, and many other prominent performers. The book includes tales of the on-and-o-the-set antics of comedian George Formby, and original accounts of his experiences working with Noel Coward and David Lean. This is not simply an autobiography, but rather a history of British cinema from the 1920s through the 1960s, and Hollywood cinema from the 1960s through the present. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

Congressional Record—House H1674

H1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE February 15, 2007 Mrs. MILLER of Michigan. Mr. IRAQ RESOLUTION IRAQ RESOLUTION Speaker, this afternoon I will have an (Ms. CLARKE asked and was given (Mr. PALLONE asked and was given opportunity to talk about the war reso- permission to address the House for 1 permission to address the House for 1 lution, but this morning I would like to minute and to revise and extend her re- minute.) just talk for a second about energy marks.) Mr. PALLONE. Mr. Speaker, the de- independence. Ms. CLARKE. Mr. Speaker, I rise bate taking place here in the House Several weeks ago we heard the today because I am very supportive of this week is long overdue. We are ap- President announce part of his agenda our troops around the globe and in par- proaching our fifth year of this war. for making America more energy inde- ticular those who are in harm’s way in This is the first time Congress is debat- pendent. But the real question is, how Iraq. I wholeheartedly support H. Con. ing the strategy President Bush wants do we get there? The President laid out Res. 63. to implement in Iraq. Congress can no a plan to place new draconian fuel-effi- Mr. Speaker, in the President’s Janu- longer stand on the sidelines, and the ciency standards on our domestic auto- ary 29, 2002, State of the Union address, President has to know that to escalate makers, which I believe is the wrong in regards to protecting America, re- the war in Iraq is not acceptable. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Doherty, Thomas, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, Mccarthyism

doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page i COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page ii Film and Culture A series of Columbia University Press Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic Henry Jenkins Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Martin Rubin Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II Thomas Doherty Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy William Paul Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s Ed Sikov Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema Rey Chow The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman Susan M. White Black Women as Cultural Readers Jacqueline Bobo Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Rhona J. Berenstein This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond Robin Wood The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music Jeff Smith Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture Michael Anderegg Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, ‒ Thomas Doherty Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity James Lastra Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts Ben Singer -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society.