Winter 2011 Full Review the .SU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Ships and Submarines of the United States Navy

AIRCRAFT CARRIER DDG 1000 AMPHIBIOUS Multi-Purpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear-Propulsion) THE U.S. NAvy’s next-GENERATION MULTI-MISSION DESTROYER Amphibious Assault Ship Gerald R. Ford Class CVN Tarawa Class LHA Gerald R. Ford CVN-78 USS Peleliu LHA-5 John F. Kennedy CVN-79 Enterprise CVN-80 Nimitz Class CVN Wasp Class LHD USS Wasp LHD-1 USS Bataan LHD-5 USS Nimitz CVN-68 USS Abraham Lincoln CVN-72 USS Harry S. Truman CVN-75 USS Essex LHD-2 USS Bonhomme Richard LHD-6 USS Dwight D. Eisenhower CVN-69 USS George Washington CVN-73 USS Ronald Reagan CVN-76 USS Kearsarge LHD-3 USS Iwo Jima LHD-7 USS Carl Vinson CVN-70 USS John C. Stennis CVN-74 USS George H.W. Bush CVN-77 USS Boxer LHD-4 USS Makin Island LHD-8 USS Theodore Roosevelt CVN-71 SUBMARINE Submarine (Nuclear-Powered) America Class LHA America LHA-6 SURFACE COMBATANT Los Angeles Class SSN Tripoli LHA-7 USS Bremerton SSN-698 USS Pittsburgh SSN-720 USS Albany SSN-753 USS Santa Fe SSN-763 Guided Missile Cruiser USS Jacksonville SSN-699 USS Chicago SSN-721 USS Topeka SSN-754 USS Boise SSN-764 USS Dallas SSN-700 USS Key West SSN-722 USS Scranton SSN-756 USS Montpelier SSN-765 USS La Jolla SSN-701 USS Oklahoma City SSN-723 USS Alexandria SSN-757 USS Charlotte SSN-766 Ticonderoga Class CG USS City of Corpus Christi SSN-705 USS Louisville SSN-724 USS Asheville SSN-758 USS Hampton SSN-767 USS Albuquerque SSN-706 USS Helena SSN-725 USS Jefferson City SSN-759 USS Hartford SSN-768 USS Bunker Hill CG-52 USS Princeton CG-59 USS Gettysburg CG-64 USS Lake Erie CG-70 USS San Francisco SSN-711 USS Newport News SSN-750 USS Annapolis SSN-760 USS Toledo SSN-769 USS Mobile Bay CG-53 USS Normandy CG-60 USS Chosin CG-65 USS Cape St. -

Virtualremembrance Day

JANUARY 2021 YEARin REVIEW A look back at 2020 Admiral’s Commentary The new year ahead VirtualRemembrance Day WalkMLK Jr. Day Observance On the Cover: USS Chung-Hoon Underway File photo by MC1 Devin Langer PHOTO OF THE MONTH Your Navy Team in Hawaii CONTENTS Welcome Commander, Navy Region Hawaii oversees two installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam on Oahu and Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands, on Kauai. As Naval Surface Group Middle Home Pacific, we provide oversight for the ten surface ships homeported at JBPHH. Navy aircraft squadrons are also co-located at Marine Corps Special Edition USS William P. Lawrence Base Hawaii, Kaneohe, Oahu, and training is sometimes also conducted on other islands, but most Navy assets are located at JBPHH and PMRF. These two installations serve fleet, fighter and family under the direction of Commander, Navy Installations Command. A guided-missile cruiser and destroyers of Commander, Naval Surface Force Pacific deploy Commander independently or as part of a group for Commander, Navy Region Hawaii and U.S. Third Fleet and in the Seventh Fleet and Fifth Naval Surface Group Middle Pacifi c Fleet areas of responsibility. The Navy, including in your Navy team in Hawaii, builds partnerships and REAR ADM. ROBB CHADWICK strengthens interoperability in the Pacific. Each YEAR year, Navy ships, submarines and aircraft from Hawaii participate in various training exercises with allies and friends in the Pacific and Indian Oceans to strengthen interoperability. Navy service members and civilians conduct humanitarian assistance and disaster response missions in the South Pacific and in Asia. Working with the U.S. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

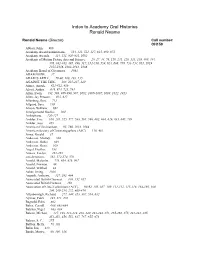

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

Read PDF < Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame

JCHB9GRXNYCN < eBook # Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography Straigh t from th e Horses Mouth : Ronald Neame, an A utobiograph y Filesize: 1.17 MB Reviews This is actually the finest pdf i have got study right up until now. It can be full of wisdom and knowledge Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Reese Morissette II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA R8BUZZDIPL8R // Doc Straight from the Horses Mouth: Ronald Neame, an Autobiography STRAIGHT FROM THE HORSES MOUTH: RONALD NEAME, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Scarecrow Press. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 328 pages. Dimensions: 8.5in. x 5.5in. x 0.9in.Now in Paperback! Ronald Neames autobiography takes its title from one of his best-loved films, The Horses Mouth (1958), starring Alec Guinness. In an informative and entertaining style, Neame discusses the making of that film, along with several others, including In Which We Serve, Blithe Spirit, Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, Tunes of Glory, I Could Go on Singing, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Scrooge, The Poseidon Adventure, and Hopscotch. Straight from the Horses Mouth provides a fascinating, first-hand account of a unique filmmaker, who began his career as assistant cameraman on Hitchcocks first talkie, Blackmail, and went on to direct Maggie Smith, Judy Garland, Walter Matthau, and many other prominent performers. The book includes tales of the on-and-o-the-set antics of comedian George Formby, and original accounts of his experiences working with Noel Coward and David Lean. This is not simply an autobiography, but rather a history of British cinema from the 1920s through the 1960s, and Hollywood cinema from the 1960s through the present. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Chapter 4: Persian Gulf

4 3HUVLDQ*XOI Australia’s participation in the Maritime Interception Force 4.1 The Maritime Interception Force was established in August 1990, in response to resolutions passed by the United Nations Security Council, to halt all inward and outward maritime traffic to Iraq to ensure compliance with the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait.1 4.2 Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ships have participated in the Maritime Interception Force since its inception, under the codename OPERATION DAMASK. In the period before the September 11 terrorist attacks, 13 RAN ships had been deployed to participate in the Interception Force. Other nations have also routinely contributed ships to the Interception Force, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Belgium, New Zealand, Italy and the Netherlands. 4.3 Following the September 11 attacks, Australia’s participation in the Interception Force was extended indefinitely and the forces deployed were incorporated into OPERATION SLIPPER, the ADF’s contribution to the International Coalition Against Terrorism. 4.4 The Maritime Interception Force conducts patrol and boarding operations in the central and northern Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Vessels containing cargoes of prohibited goods bound for Iraq are turned away or escorted back to their port of origin. Vessels containing prohibited exports from Iraq (mostly oil, but also other commodities) are detained and diverted to ports in the area for sanctions enforcement actions as required by the United Nations Security Council resolutions. The Interception Force 1 See United Nations Security Council Resolutions 661, 665, 687, 986 and 1175. 28 FORCES DEPLOYED TO THE INTERNATIONAL COALITION AGAINST TERRORISM does not conduct operations within the territorial waters of Gulf States, other than Iraq and Kuwait (which allows Interception Force ships to berth for resupply and maintenance purposes). -

US War Plans and the “Strait of Hormuz Incident”: Just Who Threatens Whom?

US War Plans and the “Strait of Hormuz Incident”: Just Who Threatens Whom? By Prof Michel Chossudovsky Global Research, January 11, 2008 11 January 2008 Instigated by the Pentagon, a bungled media disinformation campaign directed against Iran has unfolded. Five Iranian patrol boats, visibly with no military capabilities, have been accused of threatening three US war ships in the Strait of Hormuz. According to a Pentagon spokesman: The Iranian vessels “showed reckless, dangerous and potentially hostile intent,” Pentagon spokesman Bryan Whitman said. The encounter [on 6 January 2008] lasted between 15 and 25 minutes, he said. “We haven’t had an event of this serious nature recently,” Whitman said, referring to encounters between U.S. Navy vessels and Iranian warships. (Bloomberg, January 7, 2008) At one point the U.S. ships received a threatening radio call from the Iranians, “to the effect that they were closing (on) our ships and that the ships would explode — the U.S. ships would explode,” Cosgriff said. The Associated Press Pentagon Says Ships Harassed by Iran) The Pentagon said the incident was serious. It described the Iranian actions as “careless, reckless and potentially hostile” and said Tehran should provide an explanation. (Arab Times, 7 January 2008) Media Disinformation Coinciding with Bush’s Middle East trip, the intent of the Pentagon’s propaganda ploy is to present Iran as the aggressor. The patrol activities of these boats are presented as “a serious threat” and an act of “provocation”. The London Times goes even further: -

PDF EPUB} Welcome to Thebes by Glendon Swarthout Glendon Swarthout, Novelist, Dies at 74

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Welcome to Thebes by Glendon Swarthout Glendon Swarthout, Novelist, Dies at 74. Glendon Swarthout, author of "Bless the Beasts and Children" and other novels set largely in the West, died on Wednesday at his home here. He was 74 years old. Mr. Swarthout, a Michigan native who left a teaching post at Michigan State University in 1959 to move to Arizona, had suffered from emphysema for two years, his son, Miles Swarthout, said on Thursday. Mr. Swarthout wrote more than 20 novels as well as numerous short stories, plays and film scripts. Movies based on his books include "Where the Boys Are," "The Shootist" and "They Came to Cordura." Mr. Swarthout was awarded an O. Henry Prize in 1960, a gold medal from the National Society of Arts and Letters in 1972, and the Owen Wister Award, bestowed in 1991 by the Western Writers of America. His literary output was diverse. He wrote mysteries, westerns, romances and comedies in addition to children's books. His first novel, "Willow Run," was published in 1943 when he was 25. His most popular book, "Bless the Beasts and Children," has sold more than two million copies since its 1970 publication. His novel "The Cadillac Cowboys" was a protest against the Phoenix area's sprawling growth. In addition to his son, he is survived by his wife, Kathryn, his occasional co-author. The Last Shootist: A Classic Tale of the Wild West The sequel to The Shootist delivers timeless coming-of-age Western adventure, plus a new biography of Calamity Jane, the history of Fort Worth, the little-known life of a Nevada sheriff and Loren Estleman’s best of the best of the West.