The Fantasy of Ugliness in Alexander Mcqueen Col

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROSITA MISSONI MARCH 2015 MARCH 116 ISSUE SPRING FASHION SPRING $15 USD 7 2527401533 7 10 03 > > IDEAS in DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas

ISSUE 116 SPRING FASHION $15 USD 10> MARCH 2015 03> 7 2527401533 7 ROSITA MISSONI ROSITA IDEAS IN DESIGN Ideas in Design in Ideas STUDIO VISIT My parents are from Ghana in West Africa. Getting to the States was Virgil Abloh an achievement, so my dad wanted me to be an engineer. But I was much more into hip-hop and street culture. At the end of that engi- The multidisciplinary talent and Kanye West creative director speaks neering degree, I took an art-history class. I learned about the Italian with us about hip-hop, Modernism, Martha Stewart, and the Internet Renaissance and started thinking about creativity as a profession. I got from his Milan design studio. a master’s in architecture and was particularly influenced by Modernism and the International Style, but I applied my skill set to other projects. INTERVIEW BY SHIRINE SAAD I was more drawn to cultural projects and graphic design because I found that the architectural process took too long and involved too many PHOTOS BY DELFINO SISTO LEGNANI people. Rather than the design of buildings, I found myself interested in what happens inside of them—in culture. You’re wearing a Sterling Ruby for Raf Simons shirt. What happens when art and fashion come together? Then you started working with Kanye West as his creative director. There’s a synergy that happens when you cross-pollinate. When you use We’re both from Chicago, so we naturally started working together. an artist’s work in a deeper conceptual context, something greater than It takes doers to push the culture forward, so I resonate with anyone fashion or art comes out. -

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer Barbican Art Gallery, London, UK 7 October 2020 – 3 January 2021 Media View: 6 October 2020 #MichaelClark @barbicancentre The exhibition has been recognised with a commendation from the Sotheby’s Prize 2019. Michael Clark, Because We Must, 1987 © Photography by Richard Haughton This Autumn, Barbican Art Gallery stages the first ever major exhibition on the groundbreaking dancer and choreographer Michael Clark. Exploring his unique combination of classical and contemporary culture, Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer unfolds as a constellation of striking portraits of Clark through the eyes of legendary collaborators and world-renowned artists including Charles Atlas, BodyMap, Leigh Bowery, Duncan Campbell, Peter Doig, Cerith Wyn Evans, Sarah Lucas, Silke Otto-Knapp, Elizabeth Peyton, The Fall and Wolfgang Tillmans. 2020 marks the 15th year of Michael Clark Company’s collaboration with the Barbican as an Artistic Associate. This exhibition, one of the largest surveys ever dedicated to a living choreographer, presents a comprehensive story of Clark’s career to date and development as a pioneer of contemporary dance who challenged the furthest intersections of dance, life and art through a union of ballet technique and punk culture. Films, sculptures, paintings and photographs by his collaborators across visual art, music and fashion are exhibited alongside rare archival material, placing Clark within the wider cultural context of his time. Contributions by cult icons of London’s art scene establish his radical presence in Britain’s cultural history. Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts, Barbican said: “We’re thrilled to be sharing this rare opportunity for audiences to get to know the inspirational work of one of the UK’s most influential choreographers and performers, Michael Clark. -

Alexander Mcqueen: El Horror Y La Belleza

en el Metropolitan Museum of Art de Nueva York en 2011. (Fotografía: Charles Eshelman / FilmMagic) (Fotografía: en 2011. York en el Metropolitan Museum of Art de Nueva Savage BeautySavage Una pieza de la exposición Alexander McQueen: el horror y la belleza Héctor Antonio Sánchez 54 | casa del tiempo A mediados de febrero de 2010, durante la entrega de los Brit Awards, Lady Gaga presentó un homenaje al diseñador Alexander McQueen, cuya muerte fuera divul- gada en medios apenas una semana antes. La cantante, sentada al piano, vestía una singular máscara con motivos florales que se extendía hacia la parte superior de su cabeza, hasta una monumental peluca à la Marie-Antoinette: a sus espaldas se erguía una estatua que la emulaba, una figura femenina con una falda en forma de piano- la y los icónicos armadillo shoes de McQueen que la misma cantante popularizara en videos musicales. La extravagante interpretación recordaba por igual algunos momentos de Elton John y David Bowie, quienes hace tanto tiempo exploraron las posibles y fructífe- ras alianzas entre la moda, la música y el espectáculo, y recordaba particularmente —aunque con menor fortuna, como en una reelaboración minimalista y reduc- tiva— cierta edición de los MTV Video Music Awards donde, acompañada de su corte de bailarines, Madonna presentó “Vogue” ataviada en un exuberante vestido propio de la moda de Versalles. No vanamente asociados al camaleón, Madonna y Bowie han abrazado como pocos las posibilidades de la imagen: el vínculo entre la moda y la música popular ha creado —sobre todo en nuestros días— una plétora de banalidad, tontería y aun vulgaridad, pero en sus mejores momentos ha logrado visiones que colindan con el arte. -

Christian Dior Exhibition in the UK

News Release Sunday 1 July 2018 V&A announces largest ever Christian Dior exhibition in the UK Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams The Sainsbury Gallery 2 February – 14 July 2019 vam.ac.uk | #DesignerofDreams “There is no other country in the world, besides my own, whose way of life I like so much. I love English traditions, English politeness, English architecture. I even love English cooking.” Christian Dior In February 2019, the V&A will open the largest and most comprehensive exhibition ever staged in the UK on the House of Dior – the museum’s biggest fashion exhibition since Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty in 2015. Spanning 1947 to the present day, Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams will trace the history and impact of one of the 20th century’s most influential couturiers, and the six artistic directors who have succeeded him, to explore the enduring influence of the fashion house. Based on the major exhibition Christian Dior: Couturier du Rêve, organised by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, the exhibition will be reimagined for the V&A. A brand-new section will, for the first time, explore the designer’s fascination with British culture. Dior admired the grandeur of the great houses and gardens of Britain, as well as British-designed ocean liners, including the Queen Mary. He also had a preference for Savile Row suits. In 1947, he hosted his first UK fashion show at London’s Savoy Hotel, and in 1952 established Christian Dior London. This exhibition will investigate Dior’s creative collaborations with influential British manufacturers, and his most notable British clients, from author Nancy Mitford to ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn. -

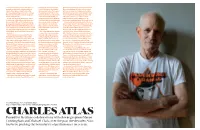

Charles Atlas

The term renaissance man is used rather too short film Ms. Peanut Visits New Atlas also created the 90-minute documentary freely these days, but it certainly applies to York (1999), before directing the Merce Cunningham: a Lifetime of Dance. And Charles Atlas, whose output includes film documentary feature The Legend in 2008, a year before Cunningham died, Atlas directing, lighting design, video art, set design, of Leigh Bowery (2002). The two filmed a production of the choreographer’s ballet live video improvisation, costume design and have remained close collaborators Ocean (inspired by Cunningham’s partner and documentary directing. – Atlas designed the lighting for collaborator John Cage) at the base of the For the past 30 years, Atlas has been best Clark’s production at the Barbican Rainbow Granite Quarry in Minnesota, the known for his collaborations with dancer and – but it was with another legendary performance unfurling against 160ft walls of rock. choreographer Michael Clark, who he began choreographer, who was himself Alongside his better-known works, Atlas has working with as a lighting designer in 1984. His a great influence on Clark, that directed more than 70 other films, fromAs Seen first film with Clark, Hail the New Puritan, was a Atlas came to prominence when on TV, a profile of performance artist Bill Irwin, mock documentary that followed dance’s punk he first mixed video and dance in to Put Blood in the Music, his homage to the renegade as his company, aided by performance the mid-1970s. diversity of New York’s downtown music scene artist Leigh Bowery and friends, prepared for Merce Cunningham was already of the late 1980s. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

Hieronymus Bosch Meets Madonna's Daughter in Jacolby Satterwhite's Epically Trippy New Video at Gavin Brown

Hieronymus Bosch Meets Madonna’s Daughter in Jacolby Satterwhite’s Epically Trippy New Video at Gavin Brown It's the artist's first New York solo show since 2013. Sarah Cascone, March 10, 2018 Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown's Enterprise. “I’m so nervous,” admitted Jacolby Satterwhite. artnet News was visiting the artist at his Brooklyn apartment ahead of the opening of his upcoming show at New York’s Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, and he was feeling some jitters. “My first solo show, no one knew who I was,” he added, noting that the pressure is way more “intense” this time around. Satterwhite’s first solo effort in the city was in 2013. “So much has happened for me since then, creatively, cerebrally, and critically. I hope of all of that comes through in what I’m showing.” Titled Blessed Avenue, the exhibition is a concept album and an accompanying music video showcasing Satterwhite’s signature visuals, a trippy, queer fantasy of a dreamscape, with cameos from the likes of Raul De Nieves, Juliana Huxtable, and Lourdes Leon (Madonna’s daughter, now studying dance at a conservatory). At 30 minutes, it’s the artist’s longest animation to date—although Satterwhite is already teasing an extended director’s cut, on tap to be shown at Art Basel in Basel with Los Angeles’s Moran Moran. Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. Blessed Avenue is also the artist’s most collaborative project to date. Satterwhite credits the many people with whom he has worked with giving him the confidence to consider his practice more broadly. -

Lucian Freud Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LUCIAN FREUD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Feaver | 488 pages | 06 Nov 2007 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847829521 | English | New York, United States Lucian Freud PDF Book Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. They are generally sombre and thickly impastoed, often set in unsettling interiors and urban landscapes. Hotel Bedroom Settling in Paris in , Freud painted many portraits, including Hotel Bedroom , which features a woman lying in a bed with white sheets pulled up to her shoulders. Freud moved to Britain in with his parents after Hitler came to power in Germany. Lucian Freud, renowned for his unflinching observations of anatomy and psychology, made even the beautiful people including Kate Moss look ugly. Michael Andrews — Freud belonged to the School of London , a group of artists dedicated to figurative painting. Retrieved 9 February The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 January Freud was one of a number of figurative artists who were later characterised by artist R. The works are noted for their psychological penetration and often discomforting examination of the relationship between artist and model. Wikipedia article. His series of paintings and drawings of his mother, begun in and continuing until the day after her death in , are particularly frank and dramatic studies of intimate life passages. Freud worked from life studies, and was known for asking for extended and punishing sittings from his models. The work's generic title, giving no hint of the specifics of the sitter or the setting, reflects the consistent, clinical detachment with which Freud approached all subjects, no matter what their relationship to him. Ria, Naked Portrait , a nude completed in , required sixteen months of work, with the model, Ria Kirby, posing all but four evenings during that time. -

Alexander Mcqueen

1 Alexander McQueen Brand Audit Jonathan Quach 2 Lee Alexander McQueen founded his brand in 1992, and decided to name it after his middle name Alexander due to his long time friend Isabella Blow. She was convinced that it would give off a more memorable impression, something to the likes of Alexander “The Great”. Isabella was an incredible influence in the success of the Alexander’s career, she had all of the contacts he needed and was instantly enthralled when she saw his first graduation collection from Central Saint Martins. She even bought the entire collection. The headquarters for his company is located in London, United Kingdom. Gucci Group acquired 51% of the Alexander McQueen brand in December of 2000. Kering, which is a French luxury goods holding company that also owns Gucci, has acquired many luxury brands since its inception, and on the Forbes Global 2000 they are McQueen’s ranked at number 763. Gucci provided Alexander McQueen with the necessary flagship store on Bond Street resources to expand the brand such as management and infrastructure. They planned on expanding into sectors such as accessories, fragrances, and ready-to-wear clothing. Alexander McQueen being a very luxurious brand that offers high-end couture, decided to widen its market with the addition of McQ. McQ is targeted toward the youthful spirit of street wear, while trying to maintain the McQueen look. The line is meant to appeal to the youth also by its price point. It is generally cheaper, but still upholds the McQueen aesthetic. Originally, it was under another label, SINV Spa, but then Alexander McQueen resumed full control of McQ in October of 2010. -

The Fashion Forward Afternoon Tea £35

THE FASHION FORWARD AFTERNOON TEA Inspired by Alexander McQueen ALEXANDER MCQUEEN Alexander McQueen was born in London in 1969. At the age of 16, McQueen was offered an apprenticeship at the Savile Row tailors Anderson and Shephard. Upon completing his Masters degree in Fashion Design at Central Saint Martin’s, McQueen met his muse, patron and life long friend Isabella Blow who famously bought his entire MA collection in 1992. Alexander McQueen shows are known for their emotional power and raw energy, as well as the romantic but determinedly contemporary nature of the collections. Integral to the McQueen culture is the juxtaposition between contrasting elements: fragility and strength, tradition and modernity, fluidity and severity. Our chefs have been inspired to create our Fashion Forward Afternoon Tea in celebration of the Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum - just around the corner from the hotel. We hope you enjoy our nod to this well known and respected British designer. If you would like to purchase tickets to the exhibition please contact our Concierge. THE FASHION FORWARD AFTERNOON TEA £35 Selection of finger sandwiches and savouries including Dorset crab and artichoke cocktail, a foie gras cornet with mango and gold quails eggs with celery salt and mustard cress. Home-made buttermilk scones with Devonshire clotted cream and jam. The Fashion Forward selection Buttermilk pannacotta with raspberry, a marzipan sable, raspberry & red pepper macaroon, cherry Genoese skull clutch and a red velvet and rose water butterfly cake. Red velvet and rose water butterfly cake inspired by Philip Treacy for Alexander McQueen AW 2008 - Cherry Genoese inspired by The Alexander McQueen Skull Clutch SS 2015 - Buttermilk pannacotta with raspberry insprired by Alexander McQueen Ready to Wear Gown AW 2008. -

ALGA Newsletter Dec 2018/Jan2019

ALGA Newsletter December 2018/Jan 2019 WHAT A YEAR! What a fantastic and busy year we’ve had here at ALGA as we celebrated our 40th Anniversary - as we take a few weeks off we just wanted to share with you a few bits of news and our plans and suggestions for Midsumma 2019. What a fine looking bunch - at the closing drinks of the Queer Legacies, New Solidarities conference in November, delegates and ALGA members lit up the candles and toasted the 40th Anniversary of ALGA. ALGA AGM At our special 40th Anniversary AGM we gathered at Hares and Hyenas to celebrate and do business. Hosted by Mama Alto, we also announced our plan in 2019 to enter into a period of consulation regarding a potential new name for the organisation. This process will consider input from our members, supporters and wider community and has been informed by discussions about the broad diversity of all our LGBTIQ+ communities. Come along to the our stall at Midsumma Carnival to learn more about how you can have your say. You can find the Annual Report on our 1. website. www.alga.org.au ALGA stall at Midsumma Carnival 2019 Drop in to see us at Carnival on Sunday 20th January any time from 11am-5pm. New copies of Secret Histories of Queer Melbourne publication available for sale on the day! Find out more: https://midsumma.org. au/what-s-on/carnival If you are interested in volunteering on our stall, please let us know. [email protected] Here’s our recommendations for events and exhibitions and other activities celebrating queer histories at Midsumma 2019 GLAM pride Victoria at Midsumma Pride March - Sunday February 3, 11am Join fellow GLAMorous LGBTIQ+ folks and allies in queerying the catalogue and curating the revolution at Pride March in Melbourne. -

1 / 56 Metropolitan Museum of Art Alexander Mcqueen: Savage Beauty Audio Guide Press Script Narrator: Andrew Bolton Voices: Sara

Metropolitan Museum of Art Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty Audio Guide Press Script Narrator: Andrew Bolton Voices: Sarah Jessica Parker, Naomi Campbell, Sarah Burton, Aimee Mullins, Shalom Harlow, Louise Wilson, Sam Gainsbury, Annabelle Nielsen, Philip Treacy, Shaun Leane, Trino Verkade, Tiina Laaokonen, Mira Chai Hyde, John Gosling, Michelle Olley 400 Exhibition Introduction [LINK TO 450] 450 Level 2: McQueen Biography 401 Dress, VOSS, 2001 (page 75) 402 Introduction: The Romantic Mind 403 Coat, Jack the Ripper, 1992 (page 32) 404 Jacket, Nihilism, 1994 (page 38) [LINK TO 451] 451 Level 2: McQueen’s Early Years 405 Bumster Trouser, Highland Rape, 1995-6 (page 5) 406 Dress, Plato’s Atlantis, Spring/Summer 2010 (page 43) 407 Introduction: Romantic Gothic 408 Dress, Horn of Plenty, 2009-10 (page 72) 409 Corset, Dante, 1996-7 (page 82) 410 Angels/Demons Collection, 2010-11(pages 93-101) 411 Introduction: Cabinet of Curiosities 412 Dress, No. 13, 1999, White Cotton spray-painted dress (page 217) 413 Shaun Leane, Coiled Corset, The Overlook, 1999-2000 (page 200) 414 Shaun Leane, Face Disc, Irere, 2003 (pages 208-209) 415 Ensemble and Prosthetic Leg, No. 13, 1999 (pages 220-223) [LINK TO 452] 452 Level 2: Aimee Mullins Continued 416 Shaun Leane, Spine Corset, 1998, page 202 417 Philip Treacy, Headdress (bird), The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, 1 / 56 autumn/winter 2008-9 (pages 205-5) 418 Armadillo Boot, Plato’s Atlantis, Spring/Summer 2010 (pages 212-13) 419 Philip Treacy, Hat of turkey feathers painted and shaped to look like butterflies,