A History of Danish Witchcraft and Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Li(Le Told Story of Scandanavia in the Dark Ages

The Vikings The Lile Told Story of Scandanavia in the Dark Ages The Viking (modern day Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes) seafaring excursions occurred from about 780 to 1070 AD. They started raiding and pillaging in the north BalCc region of Europe. By the mid 900s (10th century) they had established such a permanent presence across France and England that they were simply paid off (“Danegeld”) to cohabitate in peace. They conquered most of England, as the Romans had, but they did it in only 15 years! They formed legal systems in England that formed the basis of Brish Common Law, which at one Cme would later govern the majority of the world. They eventually adapted the western monarchy form of government, converted to ChrisCanity, and integrated into France, England, Germany, Italy, Russia, Syria, and out into the AtlanCc. They also brought ChrisCanity back to their home countries, set up monarchies, and forged the countries of Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Russia. It was the direct descendant of the Vikings (from Normandy) who led the capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade. The Romans dominated Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and England. They never could conquer the Germanic people to the north. The Germanic people sacked Rome three Cmes between 435 and 489 CE. Aer the Fall of Rome, a mass migraon of Germanic people occurred to the west (to France and England). The Frisians were at the center of a great trade route between the northern Germans (“Nordsman”) and bulk of Germanic peoples now in western Europe. High Tech in the 400s-700s The ships of the day were the hulk and the cog. -

Din Tîrgu Mureș Anul Universitar 2018-2019

Listă de repartizare a locurilor în Căminele Universității „Petru Maior” din Tîrgu Mureș Anul Universitar 2018-2019 Cazările se fac personal sau de către un membru al familiei, începând cu data de 28.09.2018 pâna în data de 01.10.2018 în intervalul orar 08:00-14:00, iar în data de 02.10.2018 în intervalul orar 08:00- 12:00. Locurile rămase neocupate vor fi redistribuite în data de 03.10.2018. Cererile pentru redistribuire se depun în data de 01.10.2018, la secretariatul DGA, sala r14, str. Nicolae Iorga. Lista cu studenții repartizați în cămin din sesiunea a 2-a de înscrieri va fi afișată în 24.09.2018, iar lista cu repartizarea pe camere în data de 25.09.2018. NR. CRT. NUME- PRENUME SPECIALIZAREA LOCALITATEA 1 ABABEI IULIAN CIG 1 HODOSA JUD HR 2 AGACHE ANDREALINA FB 2 RM 3 AJDER VLADA LMA 2 RM 4 AKMUHAMMEDOV ALLANAZAR TCM 2 TURKMENISTAN 5 ALBERT JUDIT STUDII ANGLO AM 2 SOVATA 6 ALEXA LAURA CAMELIA INFO 2 REGHIN 7 ANDRIOAEA ANDREI-ALEXANDRU ISTORIE 1 BUZAU 8 ANDRONIC IRINA ECTS 3 RM 9 ANNAGURBANOV YMAMMUHAMMET IEI 2 TURKMENISTAN 10 ANTON MIHAIL TCM 3 RM 11 APOPEI XENIA AIA 1 BICAZ JUD NT 12 AVRAM IONELA MARIA AP 3 PĂUCIȘOARA 13 BABĂ CIPRIAN ADRIAN TCM 2 TĂURENI 14 BACIU DANIELA CRISTINA AACTS 2 GĂLĂUȚAȘ-JUD HR 15 BALAN ANDREEA-CÃTÃLINA CA 1 HANGU JUD NT 16 BALÁZS RENÁTA-BERNADETTE ILSCL 1 BORSEC 17 BALINT CLAUDIU TCM 2 DUMBRAVA 18 BÂNDILÃ DRAGOŞ MSE 1 FILEA 19 BÃRÃGAN CÃTÃLIN-MIHAI IEI 1 DANES 20 BARBU BOGDAN IEI 1 SIGHIŞOARA 21 BARBU MARIA-BIANCA FB 1 CRIS 22 BARGIN DUMITRIȚA CIG 3 RM Comisia de cazare în cămin: Prorector Didactic – Prof. -

Actualizarea Programului Judeţean De Transport Rutier Public De Persoane Prin Curse Regulate, Pentru Perioada 2013–2019

Nr. 22420/18.10.2018 Dosar VI D/1 ANUN Ţ Consiliul Judeţean Mureş, în conformitate cu prevederile Legii nr.52/2003, îşi face publică intenţia de a aproba printr-o hotărâre: 1. Unele tarife și taxe locale datorate în anul 2019 bugetului propriu al Judeţului Mureş şi instituţiilor subordonate Consiliului Judeţean Mureş, precum și 2. Actualizarea Programului județean de transport rutier public de persoane prin curse regulate, pentru perioada 2013-2019. Proiectele de hotărâre sunt publicate, din data de 18 octombrie 2018, pe site-ul Consiliului Judeţean Mureş: www.cjmures.ro şi afişate la sediul instituţiei din Tîrgu Mureş, P-ţa Victoriei, nr.1. Cei interesaţi pot trimite în scris propuneri, sugestii, opinii care au valoare de recomandare, până la data de 02 noiembrie 2018, la sediul Consiliului Judeţean Mureş sau prin e-mail: [email protected]. PREŞEDINTE SECRETAR Péter Ferenc Paul Cosma Întocmit: Ligia Dascălu Verificat: director executiv, Genica Nemeş Nr.ex.2 1/1 PROIECT HOTĂRÂREA NR. ________ din ___________________ 2018 privind actualizarea Programului judeţean de transport rutier public de persoane prin curse regulate, pentru perioada 2013–2019 Consiliul Judeţean Mureş, Văzând expunerea de motive nr.22263/18.10.2018 a Preşedintelui Consiliului Judeţean Mureş, raportul de specialitate al Compartimentului Autoritatea Județeană de Transport, raportul Serviciului Juridic precum şi avizul comisiilor de specialitate. Având în vedere prevederile: - Legii nr.92/2007 privind serviciile de transport public local, cu modificările şi completările ulterioare; - Normelor de aplicare a Legii serviciilor de transport public local nr.92/2007, aprobate prin Ordinul nr.353/2007 al ministrului internelor şi reformei administrative, cu modificările şi completările ulterioare; - Hotărârii Consiliului Judeţean Mureş nr.150/2012 privind aprobarea Programului judeţean de transport rutier public de persoane prin curse regulate, pentru perioada 2013-2019, cu modificările şi completările ulterioare. -

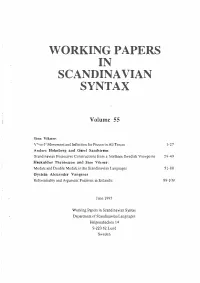

Working Papers in Scandina Vian Syntax

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINA VIAN SYNTAX Volume 55 Sten Vikner: V0-to-l0 Mavement and Inflection for Person in AllTenses 1-27 Anders Holmberg and Gorel Sandstrom: Scandinavian Possessive Construerions from a Northem Swedish Viewpoint 29-49 Hoskuldur Thrainsson and Sten Vikner: Modals and Double Modals in the Scandinavian Languages 51-88 Øystein Alexander Vangsnes Referentiality and Argument Positions in leelandie 89-109 June 1995 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax Department of Scandinavian Languages Helgonabacken 14 S-223 62 Lund Sweden V0-TO-JO MOVEMENT AND INFLECTION FOR PERSON IN ALL TENSES Sten Vilener Institut furLinguistik/Germanistik, Universitat Stuttgart, Postfach 10 60 37, D-70049 Stuttgart, Germany E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACf Differentways are considered of formulating a conneelion between the strength of verbal inflectional morphology and the obligatory m ovement of the flnite verb to J• (i.e. to the lefl of a medial adverbial or of negation), and two main alternatives are anived at. One is from Rohrbacher (1994:108):V"-to-1• movement iff 151 and 2nd person are distinctively marked at least once. The other will be suggesled insection 3: v•-to-J• mavement iff all"core' tenses are inflectedfor person. It is argued that the latter approach has certain both conceptual and empirical advantages ( e.g. w hen considering the loss of v•-to-J• movement in English). CONTENTS 1. Introduction: v•-to-J• movement ...................................................................................................................................... -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

A Journey to Denmark in 1928

The Bridge Volume 36 Number 1 Article 8 2013 A Journey to Denmark in 1928 Anton Gravesen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Gravesen, Anton (2013) "A Journey to Denmark in 1928," The Bridge: Vol. 36 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol36/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Journey to Denmark in 1928 by Anton Gravesen -Printed in Ugebladet, a Danish-American Weekly Newspaper, in 1928 over a two week period. Translated from Danish by Barbara Robertson. It is now just 3 months ago that I packed my valise and said good bye to Askov to make a journey to Denmark. It was with some mixed feelings. Half my life I have lived here and my other half over there in the old country. Ah, but off on the "steam horse" I went to Minneapolis where my daughter, Astrid, and I paid a visit to the Scandinavian-American Line's Office ~nd were received very kindly by Mr. Ellingsen, the line agent. He gave me a lot of good advice and recommendation letters to take with. That night we traveled on to Chicago where we arrived the next morning. I belong to the D. -

'A Great Or Notorious Liar': Katherine Harrison and Her Neighbours

‘A Great or Notorious Liar’: Katherine Harrison and her Neighbours, Wethersfield, Connecticut, 1668 – 1670 Liam Connell (University of Melbourne) Abstract: Katherine Harrison could not have personally known anyone as feared and hated in their own home town as she was in Wethersfield. This article aims to explain how and why this was so. Although documentation is scarce for many witch trials, there are some for which much crucial information has survived, and we can reconstruct reasonably detailed accounts of what went on. The trial of Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield, Connecticut, at the end of the 1660s is one such case. An array of factors coalesced at the right time in Wethersfield for Katherine to be accused. Her self-proclaimed magical abilities, her socio- economic background, and most of all, the inter-personal and legal conflicts that she sustained with her neighbours all combined to propel this woman into a very public discussion about witchcraft in 1668-1670. The trial of Katherine Harrison was a vital moment in the development of the legal and theological responses to witchcraft in colonial New England. The outcome was the result of a lengthy process jointly negotiated between legal and religious authorities. This was the earliest documented case in which New England magistrates trying witchcraft sought and received explicit instruction from Puritan ministers on the validity of spectral evidence and the interface between folk magic and witchcraft – implications that still resonated at the more recognised Salem witch trials almost twenty-five years later. The case also reveals the social dynamics that caused much ambiguity and confusion in this early modern village about an acceptable use of the occult. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

• Size • Location • Capital • Geography

Denmark - Officially- Kingdom of Denmark - In Danish- Kongeriget Danmark Size Denmark is approximately 43,069 square kilometers or 16,629 square miles. Denmark consists of a peninsula, Jutland, that extends from Germany northward as well as around 406 islands surrounding the mainland. Some of the larger islands are Fyn, Lolland, Sjælland, Falster, Langeland, MØn, and Bornholm. Its size is comparable to the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. Location Denmark’s exact location is the 56°14’ N. latitude and 8°30’ E. longitude at a central point. It is mostly bordered by water and is considered to be the central point of sea going trade between eastern and western Europe. If standing on the Jutland peninsula and headed in the specific direction these are the bodies of water or countries that would be met. North: Skagettak, Norway West: North Sea, United Kingdom South: Germany East: Kattegat, Sweden Most of the islands governed by Denmark are close in proximity except Bornholm. This island is located in the Baltic Sea south of Sweden and north of Poland. Capital The capital city of Denmark is Copenhagan. In Danish it is Københaun. It is located on the Island of Sjælland. Latitude of the capital is 55°43’ N. and longitude is 12°27’ E. Geography Terrain: Denmark is basically flat land that averages around 30 meters, 100 feet, above sea level. Its highest elevation is Yding SkovhØj that is 173 meters, 586 feet, above sea level. This point is located in the central range of the Jutland peninsula. Page 1 of 8 Coastline: The 406 islands that make up part of Denmark allow for a great amount of coastline. -

Religion Gb.Indd, Page 1-226 @ Pdfready 2

Religion and Politics in Pre-Modern and Modern Cultures Cluster of Excellence Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Schlossplatz 2, 48149 Münster Telefon: +49 (251) 83-0 Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics in Pre-Modern and Modern Cultures Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität WWU Münster Funding Period 01.11.2007 – 31.10.2012 Proposal Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics Proposal for the Establishment and Funding of the Cluster of Excellence "Religion und Politik in den Kulturen der Vormoderne und der Moderne" "Religion and Politics in Pre-Modern and Modern Cultures" Host university: Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität / WWU Münster Rector of the host university: Coordinator of the cluster of excellence: Prof. Dr. Ursula Nelles Prof. Dr. Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger Schlossplatz 2 Historisches Seminar 48149 Münster Domplatz 20-22 48143 Münster Phone: +49 (251) 8322211 Phone: +49 (251) 8324315 Fax: +49 (251) 8322125 Fax: +49 (251) 8324332 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Münster, April 12, 2007 Münster, April 12, 2007 Prof. Dr. Ursula Nelles Prof. Dr. Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger Rector Coordinator I Proposal Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics 1 General Information about the Cluster of Excellence Principal Investigators Surname, first name, acad. Year Institute Research title of area birth Albertz, Rainer, Prof. Dr. theol. 1943 Old Testament C, D Althoff, Gerd, Prof. Dr. phil. 1943 Medieval History A, B, D Basu, Helene, Prof. Dr. phil. 1954 Ethnology (Social B, C Anthropology) Bauer, Thomas, Prof. Dr. phil. 1961 Arabic and Islamic Studies A, B Berges, Ulrich, Prof. Dr. theol. 1958 Contemporary and Religious D History of the Old Testament Freitag, Werner, Prof. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Numen 68 (2021) 272–297 brill.com/nu The Role of Rulers in the Winding Up of the Old Norse Religion Olof Sundqvist Department of Ethnology, History of Religions and Gender Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden [email protected] Abstract It is a common opinion in research that the Scandinavians changed religion during the second half of the Viking Age, that is, ca. 950–1050/1100 ce. During this period, Christianity replaced the Old Norse religion. When describing this transition in recent studies, the concept “Christianization” is often applied. To a large extent this histo- riography focuses on the outcome of the encounter, namely the description of early Medieval Christianity and the new Christian society. The purpose and aims of the present study are to concentrate more exclusively on the Old Norse religion during this period of change and to analyze the questions of how and why it disappeared. A special focus is placed on the native kings. These kings played a most active role in winding up the indigenous tradition that previously formed their lives. It seems as if they used some deliberate methods during this process. When designing their strate- gies they focused on the religious leadership as well as the ritual system. These seem to have been the aspects of the indigenous religion of which they had direct control, and at the same time, were central for the modus operandi of the old religion. Most of all, it seems as if these Christian kings were pragmatists. Since they could not affect the traditional worldview and prevent people from telling the mythical narratives about the old gods, they turned to such aims that they were able to achieve. -

Cunning Folk and Wizards in Early Modern England

Cunning Folk and Wizards In Early Modern England University ID Number: 0614383 Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of MA in Religious and Social History, 1500-1700 at the University of Warwick September 2010 This dissertation may be photocopied Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 1 Who Were White Witches and Wizards? 8 Origins 10 OccupationandSocialStatus 15 Gender 20 2 The Techniques and Tools of Cunning Folk 24 General Tools 25 Theft/Stolen goods 26 Love Magic 29 Healing 32 Potions and Protection from Black Witchcraft 40 3 Higher Magic 46 4 The Persecution White Witches Faced 67 Law 69 Contemporary Comment 74 Conclusion 87 Appendices 1. ‘Against VVilliam Li-Lie (alias) Lillie’ 91 2. ‘Popular Errours or the Errours of the people in matter of Physick’ 92 Bibliography 93 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my undergraduate and postgraduate tutors at Warwick, whose teaching and guidance over the years has helped shape this dissertation. In particular, a great deal of gratitude goes to Bernard Capp, whose supervision and assistance has been invaluable. Also, to JH, GH, CS and EC your help and support has been beyond measure, thank you. ii Cunning folk and Wizards in Early Modern England Witchcraft has been a reoccurring preoccupation for societies throughout history, and as a result has inspired significant academic interest. The witchcraft persecutions of the early modern period in particular have received a considerable amount of historical investigation. However, the vast majority of this scholarship has been focused primarily on the accusations against black witches and the punishments they suffered.