MUSIC; a Grievous Angel, a Busy Ghost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Z 102 Coltrane, John / Giant Steps Z 443 Cooke, Sam

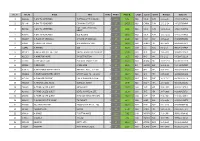

500 Rank Album 102 Coltrane, John / Giant Steps 285 Green, Al / I'm Still in Love With You 180 Abba / The Definitive Collection 443 Cooke, Sam / Live at the Harlem Square Club 61 Guns N'Roses / Appetite for Destruction 73 AC/DC / Back in Black 106 Cooke, Sam / Portrait of a Legend 484 Haggard, Merle / Branded Man 199 AC/DC / Highway to Hell 460 Cooper, Alice / Love It to Death 437 Harrison, George / All Things Must Pass 176 Aerosmith / Rocks 482 Costello, Elvis / Armed Forces 405 Harvey, PJ / Rid of Me 228 Aerosmith / Toys in the Attic 166 Costello, Elvis / Imperial Bedroom 435 Harvey, PJ / To Bring You My Love 49 Allman Brothers Band / At Fillmore East 168 Costello, Elvis / My Aim Is True 15 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Are You Experienced? 152 B-52's / The B-52's 98 Costello, Elvis / This Year's Model 82 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Axis: Bold as Love 34 Band / Music from Big Pink 112 Cream / Disraeli Gears 54 Hendrix, Jimi Experience / Electric Ladyland 45 Band / The Band 101 Cream / Fresh Cream 389 Henley, Don / The End of the Innocence 2 Beach Boys / Pet Sounds 203 Cream / Wheels of Fire 312 Hill, Lauryn / The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill 380 Beach Boys / Sunflower 265 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Cosmo's Factory 466 Hole / Live Through This 270 Beach Boys / The Beach Boys Today! 95 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Green River 421 Holly, Buddy & the Crickets / The Chirpin' Crickets 217 Beastie Boys / Licensed to Ill 392 Creedence Clearwater Revival / Willy and the Poor Boys 92 Holly, Buddy / 20 -

É£Žé¸Ÿä¹É˜Ÿ Éÿ³æ

飞鸟ä¹é ˜Ÿ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) Sweetheart of the Rodeo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sweetheart-of-the-rodeo-928243/songs Fifth Dimension https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fifth-dimension-223578/songs Mr. Tambourine Man https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mr.-tambourine-man-959637/songs Younger Than Yesterday https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/younger-than-yesterday-2031535/songs Ballad of Easy Rider https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ballad-of-easy-rider-805125/songs (Untitled) https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/%28untitled%29-158575/songs Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrds-1018579/songs Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/dr.-byrds-%26-mr.-hyde-1253841/songs Byrdmaniax https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrdmaniax-1018576/songs Byrdmaniax https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/byrdmaniax-1018576/songs Farther Along https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/farther-along-1397186/songs Easy Rider https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/easy-rider-1278371/songs History of The Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/history-of-the-byrds-16843754/songs The Byrds https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-byrds-16245109/songs There Is a Season https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/there-is-a-season-7782757/songs 20 Essential Tracks from the Boxed https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/20-essential-tracks-from-the-boxed-set%3A- Set: 1965–1990 1965%E2%80%931990-38341997/songs The -

Sam Quinn's Posthumous Visit with Gram Parsons by Carole Perkins 2008

Sam Quinn's Posthumous Visit With Gram Parsons by Carole Perkins 2008 Sam Quinn and his band, the everybodyfields, recently stayed at The Joshua Tree Inn where legendary singer/songwriter Gram Parsons died from a drug and alcohol overdose in 1973 at the age of 26. Quinn, Jill Andrews, Josh Oliver, and Tom Pryor, comprise the everybodyfields whose music has been described as, "a fresh set of fingerprints in the archives of bluegrass, country, and folk music." The band was touring the west coast when Quinn discovered the band was booked to stay at The Joshua Tree Inn. The Joshua Tree Inn is a simple but mythical motel in California, about 140 miles east of Los Angeles. It was popular in the fifties for Hollywood rabble rousers and trendy in the seventies for rockers and celebrities. These days, the main attraction is the room Parsons passed away in, room Number Eight, where thousands of fans pilgrimage every year to pay homage to Parsons. Quinn says he's been a fan of Parsons since he was eighteen but never dreamed he'd be sharing a wall with Parson's old motel room one day. "It was really far out to find out we would be staying in the Joshua Tree Inn. I had just woken up in our van that was parked about a mile away. I knew we'd be in the vicinity of where Gram died but sharing a wall with Gram, no, not a chance," he says. "So we walk into the lobby and the lady at the front desk gives me a key to room Number Seven, the room right next to the one Gram died in. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 4-17-1981 Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, April 17, 1981" (1981). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7140. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7140 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors debate news philosophies By Doug O’Harra of the Society of Professional Montana Kaimin Reporter Journalists about a controversy arising out of the Weekly News’ , Two nearly opposite views of reporting of the trial and senten journalism and newspaper cing, and a Missoulian colum coverage confronted one another nist’s subsequent reply several yesterday afternoon as a Mon days later. tana newspaper editor defended On Sept. 3, Daniel Schlosser, a his paper’s coverage of the trial 36-year-old Whitefish man, was and sentencing of a man con sentenced to three consecutive 15- victed of raping young boys. year terms in the Montana State Before about 70 people, packed Prison for three counts of sexual in the University of Montana assault. -

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC (Biography)

DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC (biography) ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME MEMBER CHRIS HILLMAN AND THE DESERT ROSE BAND~ACOUSTIC TO PERFORM IN A RARE APPEARANCE Joining Chris Hillman in this acoustic appearance are John Jorgenson on guitar/mandolin, Herb Pedersen on guitar and Bill Bryson on bass. Chris Hillman was one of the original members of The Byrds, which also included Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, Gene Clark and Michael Clarke. The Byrds were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. After his departure from the Byrds, Hillman, along with collaborator Gram Parsons, was a key figure in the development of country-rock. Hillman virtually defined the genre through his seminal work with the Byrds and later bands, The Flying Burrito Brothers and Manassas with Steven Stills. In addition to his work as a musician, Hillman is also a successful songwriter and his songs have been recorded by artists as diverse as; Emmylou Harris, Patti Smith, The Oak Ridge Boys, Beck, Steve Earl, Peter Yorn,Tom Petty, and Dwight Yoakam. In the 1980s Chris formed The Desert Rose Band which became one of country music’s most successful acts throughout the 1980s and 1990s, earning numerous ‘Top 10’ and ‘Number 1’ hits. The band’s success lead to three Country Music Association Awards, and two Grammy nominations. Although the Desert Rose Band disbanded in the early 1990s, they performed a reunion concert in 2008 and have since played a few shows together in select venues. Herb Pedersen began his career in Berkeley, California in the early 1960′s playing 5 string banjo and acoustic guitar with artists such as Jerry Garcia, The Dillards, Old and in the Way, David Grisman and David Nelson. -

History of Rock and Roll Unit 2 02/18/2014

History of Rock and Roll Unit 2 02/18/2014 Bob Dylan Born as Robert Zimmerman 1941 in Minnesota Played in lots of bands singing POP in high school, interest in rock and roll led to American Folk in college Woody Guthrie- Bob Dylan’s musical idol o Goes to NY mental hospital to visit Guthrie with Huntingtons disease Begiins playing in clubs in Greenwich Village Signed to Columbia Records by John Hammond, against Columbia Record’s wishes “Blowin in the Wind”- most popular song at this time, is widely recorded and becomes an international hit for Peter, Paul and Mary setting precedent for many other artists who have hits with Dylan’s songs “Times They are A-Changin’”- Folk songs there is a structure and a repeating moral… About Vietnam war.. Don’t criticize what you cant understand o Produced by Tom Wilson Album: Another Side of Bob Dylan- “My Back Pages”- “ah, but I was so much older then, im younger than that now”—he starts writing about himself o This song has been interpreted as a rejection of Bob’s earlier personal and political idealism, illustrating a growing disillusionment with the 1960s folk protest movement, and his desire to move in a new direction “Subterranean Homesick Blues”—Inspired by Chuck Berry’s “Too much monkey business” o this is Dylan’s first single to chart in the US peaking at #39 “Mr. Tambourine Man”—The Byrd’s version reached #1 in US and UK and is the title track of their first album. “Like a Rolling Stone”—“How does it feel, hoe does it feel to be without a home like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone?” o #2 in US, #4 in UK o Mike Bloomfield-guitar o Al Kooper-Improvised the organ rif 1965 Newport Folk Festival- Dylan is warmly received where he is considered the leading songwriter Album Blonde On Blonde- Producer Bob Johnston Dylan crashes his motorcycle near his home in Woodstock, New York. -

The Byrds the Very Best of the Byrds Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Byrds The Very Best Of The Byrds mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Very Best Of The Byrds Country: Canada Released: 2008 Style: Folk Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1369 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1614 mb WMA version RAR size: 1322 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 227 Other Formats: ADX MP4 MPC DMF XM AIFF AU Tracklist 1 Mr. Tambourine Man 2:33 2 I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better 2:35 3 All I Really Want To Do 2:06 4 Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is A Season) 3:53 5 The World Turns All Around Her 2:16 6 It's All Over Now, Baby Blue 4:55 7 5D (Fifth Dimension) 2:36 8 Eight Miles High 3:38 9 I See You 2:41 10 So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star 2:09 11 Have You Seen Her Face 2:43 12 You Ain't Goin' Nowhere 2:37 13 Hickory Wind 3:34 14 Goin' Back 3:58 15 Change Is Now 3:25 16 Chestnut Mare 5:09 17 Chimes Of Freedom 3:54 18 The Times They Are A-Changin' 2:21 19 Dolphin's Smile 2:01 20 My Back Pages 3:11 21 Mr. Spaceman 2:12 22 Jesus Is Just Alright 2:12 23 This Wheel's On Fire 4:47 24 Ballad Of Easy Rider 2:04 Credits Artwork By – David Axtell Compiled By – Sharon Hardwick, Tim Fraser-Harding Photography By – Don Hunstein, Sandy Speiser Notes Packaged in Discbox Slider. -

Flying Burrito Brothers' Gilded Palace of Sin (33 1/3 Series) Online

JcOpW [Mobile library] Flying Burrito Brothers' Gilded Palace of Sin (33 1/3 Series) Online [JcOpW.ebook] Flying Burrito Brothers' Gilded Palace of Sin (33 1/3 Series) Pdf Free Bob Proehl *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #6708727 in Books 2017-01-24 2017-01-24Formats: Audiobook, MP3 Audio, UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 6.75 x .50 x 5.25l, Running time: 4 HoursBinding: MP3 CD | File size: 54.Mb Bob Proehl : Flying Burrito Brothers' Gilded Palace of Sin (33 1/3 Series) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Flying Burrito Brothers' Gilded Palace of Sin (33 1/3 Series): 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Iconic Album Deserves Far Better Than ThisBy TomContinuum Books' selection of The Gilded Palace of Sin for its 33 1/3 series is absolutely deserved. The album stands as a trailblazing standard of the "country-rock" genre and Gram Parson's finest effort. Unfortunately, author Bob Proehl doesn't come anywhere near doing justice to this iconic masterpiece. This is more of a brief history of the Flying Burrito Brothers than a close look at their debut album. There are no absolutely no details of the 1968 recording sessions. Proehl simply did not bother doing the necessary research. The album's producers, Henry Lewy and Larry Marks, aren't even mentioned. Neither can be found any reference to drummers Popeye Phillips or Eddie Hoh who played on five of the eleven tracks. -

The Byrds Sweetheart of the Rodeo Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Byrds Sweetheart Of The Rodeo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Sweetheart Of The Rodeo Country: US Style: Folk Rock, Country Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1551 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1330 mb WMA version RAR size: 1885 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 784 Other Formats: DXD RA VQF AUD AAC MPC MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Original LP You Ain't Goin' Nowhere 1-1 2:38 Written-By – B. Dylan* I Am A Pilgrim 1-2 3:42 Arranged By – C. Hillman*, R. McGuinn*Written-By – Traditional The Christian Life 1-3 2:33 Written-By – C. Louvin*, I. Louvin* You Don't Miss Your Water 1-4 3:51 Written-By – W. Bell* You're Still On My Mind 1-5 2:26 Vocals – Gram ParsonsWritten-By – L. McDaniel* Pretty Boy Floyd 1-6 2:37 Written-By – W. Guthrie* Hickory Wind 1-7 3:34 Vocals – Gram ParsonsWritten-By – B. Buchanan*, G. Parsons* One Hundred Years From Now 1-8 2:43 Written-By – G. Parsons* Blue Canadian Rockies 1-9 2:05 Written-By – C. Walker* Life In Prison 1-10 2:47 Written-By – J. Sanders*, M. Haggard* Nothing Was Delivered 1-11 3:24 Written-By – B. Dylan* Additional Master Takes All I Have Are Memories 1-12 2:48 Vocals – Kevin KelleyWritten-By – K. Kelley* Reputation 1-13 3:09 Written-By – J. T. Hardin* Pretty Polly 1-14 2:55 Written-By – C. Hillman*, R. McGuinn* Lazy Days 1-15 3:28 Written-By – G. Parsons* The Christian Life 1-16 2:29 Vocals – Gram ParsonsWritten-By – C. -

ARSC Journal, Fall 1989 195 Book Reviews

Book Reviews The major problem some people will have with this book involves the criteria for inclusion. But even here it is not too difficult to fault Stambler's reasoning. The major names are here, and covered well. The lesser-known artists are for the most part not included, or mentioned in other entries. However, there are some admirable examples of influential but lesser-known, bands or artists given full coverage, (e.g., The Blasters, Willy Deville, Nils Lofgren, Greg Kihn, Richard Hell and others). And some attempt has been made to include representative heavy metal, rap and punk artists, though not many appear. While it is obvious that in such an all-encompassing work there are bound to be some errors of omission, how could Stambler leave out a band such as R.E.M.? And how can there be an entry for Ian Matthews' semi-obscure band Southern Comfort, yet nothing for Richard Thompson or Fairport Convention? While the book seems to be mainly accurate and fact-filled, some errors did creep in. In the Mike Bloomfield entry, the late guitarist was credited for a solo album by his cohort Nick Gravenites; The Byrds' 1971 LP "Byrdmaniax" appears without the final letter, and at one point Nils Lofgren's pro-solo band Grin is referred to as Grim. There are no doubt a few others, but admittedly none of these errors are fatal. And though the inclusion of 110 pages of appendices in the form of Gold/Platinum Records and Grammy/Oscar winners is nice, I think most of us would prefer an index.