Chapter XXIV on the Miner's Exchange List, the Most Interesting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rnmcle INCLUDING

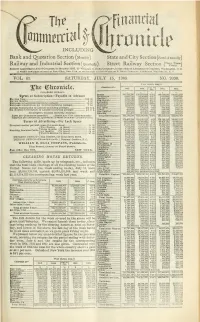

. 1 i . financial nnrnwrcia WJ rnmcle INCLUDING Bank and Quotation Section (Monthly) State and City Section (semi-Annually) Th l!S Railway and Industrial Section (quarterly) Street Railway Section ( vCJ-iy" ) Entered according to Act of Conness, tn the year l!io5, by Wn.i.iwi H. Dava Company, in the ottloeof Librarian of Confess. Washington. l>. c« VOL. 81. SATURDAY, JULY 29 1905. NO. 2092. Week ending July 22 Clearings at— Inc. or 1905. 1904 1902 ghc (IDhrouicle. Dec. PUBLISHED WEEKLY. * Boston 142.531,487 127.549.530 --It 7 125.820 078 126,379,801 Terms oi Subscription—Payable in Advance Providence 7,250,800 6.110,800 --181 6,289,800 0,027.100 2,908.496 2,500,303 --15-9 For One Year $10 00 Hartford 2.884.353 2.481.784 New Haven- 2.339,-28 2,288.301 --22-3 2 03i 1.510,800 For Six Months 6 00 Springfield 1,038.497 1.480,1 CO --107 1 312.791 I .170 European Subscription (including postage) 18 00 98.-, Worcester 1,561, 426 1.814,932 --188 1 580 180 1 57 1 (including postage) European Subscription Six Months 7 50 Portland 1.506,269 1 531 07.- -1 7 1,449.292 1.168 727 Annnal Subscription in London (including postage) £2 14s. Fall River 676,059 021.352 +8 3 7,vl,v.-,l ' 479,987 453.727 D 7 55 619,712 Six Months subscription in London (including postage) £1 lis. Lowell -fc New Bedford 524.008 400,491 +29 403.535 471 822 Subscription includts rollowing Sections— Holyoke 376,362 495 479 -24 403.883 : 778 Bank and Quotation (monthly) I State and City (semiannually) Total New England. -

CHALFONTE Do Pref

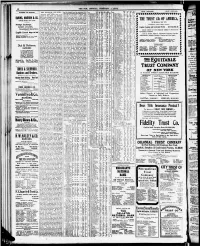

XEW-YOKK DAILY TRIBUNE. SATURDAY. FEBKUASY 23. Iff^. IS MISCELLANEOUS SECFBITIES. COFFEE QUOTATIONS. TRADE IN CHICAGO. Dividend Notices. Winter Resorts. Winter Resorts. OTurT.iahed by Barucb Brothers, No. William-**.) \u25a0 [BT TELEGRAPH TO THE TRTBrV* ] ' ' ' 27 STOCKS. r OF \u25a0 READING -*>.Vw- Havr* C".'- Havr* Chicago, Feb. 24.—Much activity \u25a0*•*\u25a0 areua*4 la OFFICE COMPANY. WKCIMA. mderio H. Hatch. No. SO Broad-at) clwlng closing _„_ £•*- PHIUADBTJ'HIA. January 21. 1905. MTW-JERarT. crural**** tor prices. New-York price*, If*w-York th« corn market to-day by the vigor or the> demand BOARD OF DIRECTORS HAVE DE- *" closing 24, eloslns; r£H.B int. I Feb. 24. ! Feb. Trading- considerably what dlridsjld 2 per cent, I I int. I New-Tork prices. | prices, in that market exceeded clared from the Mlearnlcxs a of Irat*, Iperiod. IBid. [Ask'4. ; New-York \u25a0was wheat, and while both wheat and on th« First Preferred Stock of the Company, to b» paid parity. Feb. 24. parity. Feb. 24. dona In March 9U*. to Springs * -" February «.«0©«.85 • August 70S 7.20j?7.25 firm, oonaidar- op 1805. ta« stockholders of record at the Virginia Hot B*nk Note I J Q-M C2H .6.87 corn were the strength of th» Utter elosn of business February 20th, 1906. Check* will N» HOTEL T^B-rlcaa Saarcb ....6.57 f1.fi0ig6.65 September .7.13 who WINDSOR *_^-can Brass Q-F 115 7.8097.80 ably other, advance la r<?w Taw* <MB**\M9mm An. 122H April 6.91 f1.7556.50 October ....7.17 7.55Q7.40 exceeded that of the and the STkwith A.the»?«<**»»l<Jar«.• have fll*d dividend orders g* May B.M o.oofifl.ft3.Nov«mb«r ..7.21 7.40^7.45 it was more material. -

I1t1j1l Ii E It I

11 T i1t1j1l ii e It i I J- I COMPANIES 1804 Jibes Low Clai NI TIltST COMPANIES TRlST Mid the benefit from the economies Intro CJbQl A ir BANKERS AND BROKERS TUB FINANCIAL SITUATION Sultt fit ill tnt C5iaIIgqIILOw Stiff tit ill tng u u uu vi- Steel Corpora 73- 134 f the operations of the R8 InGtN3d Bt M 9M 4 M MM 8H 100 Int Pump pf 72 72 + Sentiment within certain lines is all duo not yet begun to accrue The 188 KCFtS4M ll 80J4 80 MM + M tfW- 7 400 Iowa Central pf 40M 39 39 2 powerful in Wall Street and sentiment reasonable conclusion at present seems 3KQ PcHt B7 87 87 + V4 W 1- 850KanCSouthpf 874 364 304 Ill 7zmariCySoSJ TOH 9 200 pf 67 06M 864- 174 j fL there In now as ns a few weeks that as only one month of the current TOM 70 704 + i KC Ft Scott BARING MAGOUN CO I Ky Cent 4s 17M 7 7 + M 98 97 < lOOKnlcMceCo 9 9 9 3 and almost a few days ago It was colored- quarter hue elapsed It is too early for the 2 21 KIngs Co 4 7 8187 M 874 M- 500 Lake Erie 4 West 304 30 304 + AMERICA may prob- ¬ 107 107 I TOE CO OF optimism change opinions as to the 1 IO6 106 13618 109 TRUST at least with It formation of definite IO6 1O64 + Louis 4 Nashville 1i I Capta- I 1 15 Wall Street New York again as readily hut its present mood able results of the Corporations business In 2lLacksteerMD3W88 i tafi 93 US 8950 Manhattan 1454 1434 1434 is unmistakable It was pretty clear a the entire term even if the business of tho 1 LErleftWlatlUM 1M 1174 + 2 M 1 K 115 M- 570 Mel Street Ry 123 131 122 2 149 BroadWay New YorK liiiplus < I MM 700 90 89M 884 week ago that enthusiasm -

February 1905

VOL. XVII. No. 2. FEBRUARY, 1905. WHOLE No. 77. RE&ME VILLAS ALL CONCRETE ILLUSTRATED 85 CHAS. DE KAY THE PERFECT THEATRE ILLUS- TRATED ...... IOI J. E. O. PRIDMORE THE GERMAN EXHIBIT OF ARTS AND CRAFTS ILLUSTRATED . 119 IRVING K. POND WYCHWOOD." THE HOUSE OF '.MR. CHAS. L. HUTCHINSON IL- LUSTRATED ...... 127 JOHN BAPTISTE FISCHER THE ARCHITECT IN RECENT FIC- TION. ,..,.. 137 HERBERT CROLY NOTES AND QUERIES . 141 Subscription Yearly, $3.00 PUBLISHED MONTHLY iT OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: Ncs. 14 and 16 VESEY STREET, NEW YORK CITY. WESTERN OFFICE: I2O RANDOLPH ST., CHICAGO, ILL. X* >yz a * *-*'"--* fy*-;:" #.'$*'*!% ^"f''*'*! _ m^. _ EXAMPLES OF MODERN FRENCH HARDWARE. Russell & Erwin Mfg. Co., Art Department 26 West 26th St., New York City. Made by Mai-son Fontaine, Paris. Concessionaires pour Maison Fontaine. tlbe VOL XVII, FEBRUARY, 1905. NO. 2. Villas All Concrete. He that has a house to put's head in, Now true it is that untouched surf- has a good headpiece, remarks King aces of shingle on roof and walls, of a Lear. That cottage you are going to bright day, have in shadow certain build by the seashore or in the hills, that lovely tones for eyes that note such home for the summer months which things with loving care, tones of mauve, must not cost more than seven thousand of violet, of amethyst. And in direct and surely comes to thirteen, what will light, seen nearby, thev are finely sil- you have it made of wood or brick? vern. But in the long run they have the half "timber and brick or stone? or defect of in color the per- gloominess ; gen- adventure concrete and a tiled roof? eral impression is more than dull. -

Romcle INCLUDING

financial romcle INCLUDING Bank and Quotation Section (Monthly) State and City Section (seini-Amraaiiy) Railway and Industrial Section (Quarterly) Street Railway Section 05 ('""yCJi™ ) Entered aooordlng to Act of Congress, In the year 1905, by William k. Daha Company, in the ollioe of Librarian of Confess, Washington, I). U. A weekly newspaper entered at Post Office. New York, as second-cliss uiniter— William B. Dana Companv, Publishers, 76^ Pine St., N. T. VOL. 81. SATURDAY, JULY 15, 1905. NO. 2090. II eek ending July 8 Clearings at— Inc. ur 1905. 1004. 1903. 1902. £hc Chronicle. Dec. PUBLISHED WEEKLY. Boston 156.738.700 116,353.929 +347 140.010,645 143,821.523 Tjrms ol Subscription—Payable in Advance Providence 0,950,700 6.159,800 --34 7 0.052,000 0,0-40,600 8.&S2 339 • -20 For One Year $10 00 Hartford 3.218,872 6 8.432.312 3.103,221 New Haven- 2.573.94b 2,800,751 --11-0 2.233.463 2,178,040 For Six Months 6 00 2,313,085 1.544,325 --19 8 2.028.316 1.820,256 (Including Springfield fnropean Subscription postage) 13 00 Worcester 1,798,005 1,230,491 --16-2 1,811.190 1.040.120 uropean Subscription Six Months (including postage) 7 60 Portland 1.676.825 1.568.312 +0-9 1,857.699 1,800.320 Annual Subscription in London (including postage) £2 14s. Fall River 731,604 759,013 -3-6 788.304 805,730 6ix Months Subscription in London (inoluding postage) £1 lis. -

Worlds Fairs

I TilE WASHINGTON TIMES FRIDAY JUNK 17 1901 q EXCURSIONS Trading in Southern Pacific COMIC PACE CONTEST EXCURSIONS EXCURSIONS TUAILOSE MONDAY NIGHT FISHINC I AND Chesapeake Ohio By Still Dominating the Market HUNTINGCol- Competitors Should Remember SCENIC ROUTE TO THE I That orado possesses some ot the Only Four Characters Are Allowed Onset fishing and hunt Injr grounds NEW YORK STOCK MARKET NEWS AND GOSSIP on earth the dense forests bcint STOCKHOLDING MARKETS in Making Picture > the natural covers for elk deer Reported by W D Hlbbs Co 1419 F OF STOCK and other myriads of FAIRS- streams teem with WORLDS t Street Members New York Stock Exchange mountain I trout its lakeswhile full of attrac- ¬ Chicago Board et Trade and Washington Stock WASHINGTON angler The circle for producing comic foods tions for the are also the LOUIS MO Hxulwage Only a limited amount of business will appear haunt of millions of geese ducks T FAIRLY WELL Open High Low 2 pm for the last time tomorrow and other wild fowls Through the Grandest Scenery East of the Rockies Amal Copper Wfc 49 49 49Vt was done on the local exchange today Aspirants for the prizes may send In Amer Loco 19 19 19 19 and most of it was confined to Wash- ¬ the results of their efforts us Into as The Fast Trains to Am Car Found 1 17 1 lilA ington Street Railway preferred and Monday night The committee will Amer Smelt 53 54 61 64 Mergentlialer The former stock sold EXCURSION RATES FROM WASHINGTON faces Tuesday begin ¬ A T S F 72 1S 71 down from 57 the first sale to 66 take the and look COLORADO 11 -

January 9, 1909

Published every Saturday by WILLIAM B. DANA COMPANY. Front, Pine and VOL. 88. JANUARY 9, 1909. NO. 2272. I Deneystec Sts., N. Y. C. WIDIam B. Dana Frost.: Jacob :Seibert Jr.. VIce-Prest. and 9ec., Arnold G. Dana, Treas. Ad,tresses of ail, Office or the Company. CLEARINGS-FOR DECEMBER,SINCE AN U ARY A N D FOR WEEK EN DIN.G JANUARY 2 December. Twelve Months. Week ending January Clearings al- 2. Inc. or Inc. or Inc. cr 1903. 1907. Dec. 1908. 1907. De'. 1909. 1903. Dec. 1907. 1906. 8 90 S New York 9,266,286,510 5,349,926,947 +i3.2 79,275,890,256 87,132,168,381 -9.1 1,730.143,393 1,335.387,844 +33.3 2,125,942,186 2,392,770,430 Philadelphia 571.340.183 492,894,433 +15.9 5,937,754,106 7,161,060,440 -17.1 129,505,632 117.181,435 +10.5 156.237,758 158,398;541: Pittsburgh 182,525,761 203,043,736 -10.1 2,064,632,960 2,743,570.484 -24.8 :35,836,473 47,410,102 -24.4 52,448,316 55,028,930. Baltimore 120,620,1)31 104,208,601 +15.8 1,240,904,390 1,472.911,207 -15.7 29,341,094 24,433,998 Buffalo +20.1 32,013,695 30.1319,555 36,480,529 31,494,577 +15.8 409,086,607 434,689,13'15 -5.9 6,716,576 6,772,569 -0.8 8,521,209 7,982,586 Albany 25,902,931 19,646,527 +31.8 278,976,213 338.582,960 -17.6 5.078,322 4,278,701 +18.7 67201,817 5,714,940• Washington 26,766,731 20,736,729 +29.1 278,079,235 :302,108,404 -9.0 5,125,018 4,689,377 +9.3 +10.8 6,597,799 5,876;453. -

14 Wall Street Building (Bankers Trust Building)

Landmarks Preservation Commission January 14, 1997; Designation List 276 LP-1949 14 WALL STREET BillLDING (Formerly Bankers Trust Building), 14 Wall Street (aka 8-20 Wall Street; 1-11 Nassau Street; and 7-15 Pine Street), Manhattan. Built 1910-12; architect Trowbridge & Livingston; addition, 1931-33, architect Shreve, Lamb & Harmon. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 46, Lot 9. On September 17, 1996, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the 14 Wall Street Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1). 1 The hearing was continued to November 19, 1996 (Item No. 1). The hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of Jaw. Three witnesses -- Council Member Kathryn Freed and representatives of the Municipal Art Society and New York Landmarks Conservancy - spoke in favor of designation; there were no speakers in opposition. The owner of the property has not expressed opposition to this designation. Summary The 14 Wall Street Building, with its distinctive pyramidal roof, is one of the great towers that define the lower Manhattan sky line. Located in the heart of the financial district, the building was erected in 1910-12 for the Bankers Trust Company. Symbolizing the importance of the company, the 539-foot-high 14 Wall Street Building was the tallest bank building in the world when it was completed. Designed by the prestigious firm of Trowbridge & Livingston, this granite-clad tower incorporated the latest in building technologies and was one of the first buildings to employ a cofferdam foundation system. -

14 Wall Street Building Designation Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission January 14, 1997; Designation List 276 LP-1949 14 WALL STREET BUILDING (Formerly Bankers Trust Building), 14 Wall Street (aka 8-20 Wall Street; 1-11 Nassau Street; and 7-15 Pine Street), Manhattan. Built 1910-12; architect Trowbridge & Livingston; addition, 1931-33, architect Shreve, Lamb & Harmon. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 46, Lot 9. On September 17, 1996, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the 14 Wall Street Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1).1 The hearing was continued to November 19, 1996 (Item No. 1). The hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Three witnesses -- Council Member Kathryn Freed and representatives of the Municipal Art Society and New York Landmarks Conservancy -- spoke in favor of designation; there were no speakers in opposition. The owner of the property has not expressed opposition to this designation. Summary The 14 Wall Street Building, with its distinctive pyramidal roof, is one of the great towers that define the lower Manhattan skyline. Located in the heart of the financial district, the building was erected in 1910-12 for the Bankers Trust Company. Symbolizing the importance of the company, the 539-foot- high 14 Wall Street Building was the tallest bank building in the world when it was completed. Designed by the prestigious firm of Trowbridge & Livingston, this granite-clad tower incorporated the latest in building technologies and was one of the first buildings to employ a cofferdam foundation system. -

September 24, 1904

N. W. HARRIS & CO., BANKERS, PINE STREET COR. WILLIAM, CHICAGO. NEW YORK. boston. Deal Exclusively in Municipal, Rail- road and other Bonds adapted for trust funds and savings. I88UB TRAVELERS' LETTERS 01 ORBDI'l AVAILABLE IN ALL PARIS OB THE WORLD. QUOTATIONS FURNISHED FOB PURCHASE. BALK OR EXCHANGE. If you wish to BUY or SELL TRACTION COMPANY BONDS OR STOCKS, GAS COMPANY BONDS OR STOCKS, FERRY COMPANY BONDS OR STOCKS, INDUSTRIALS, WRITE TELEGRAPH, TELEPHONE, OR CALL ON GUSTAVUS MAAS, 30 BROAD STREET, - NEW YORK. ESTABLISHED 1868. KING, HODENPYL & CO., BANKERS S BROKERS, V "Wall Street, 2 XT La Salle Street, NEW YOIUK. CHICAGO. STREET RAILWAY, GAS AND ELECTRIC LIGHT SECURITIES, WHITAKER & COMPANY, BOND AND STOCK BROKERS, 300 North Fourth Street, - St. Louis, Mo INVESTMENT SECURITIES AND MUNICIPAL BONDS. WE BUY TOTAL ISSUES OF CITIES, COUNTIES, SCHOOL AND STREET RAILWAY COMPANY BONDS. MONTHLY CIRCULAR QUOTING LOCAL SECURITIES MAILED ON APPLICATION Chartered 1836 GIRARD TRUST COMPANY PHILADELPHIA, PA. CAPITAL, $2,500,000 SURPLUS, $7,500,000 Acts as Trustee of Corporation Mortgages, Acts as Executor, Administrator, Trustee, Registrar and Transfer Agent Assignee and Receiver. Assumes Entire Charge of Real Estate. Depositary under Plans of Reorganization. Interest Allowed on Individual and Corpo- Financial Agent for Individuals or ration Accounts. Corporations. Safes to Rent in Burglar-Proof Yaults. OFFICERS. EFFINGHAM B. MORRIS, President. WM. NEWBOLD ELY, First Vice-President. ALBERT ATLEE JACKSON, Second Vice-President. CHARLES JAMES RHOADS, Treasurer. EDW. SYDENHAM PAGE, Secretary. WILLIAM E. AUMONT, Trust Officer. MINTURN T. WRIGHT, Peal Estate Officer. GEORGE TUCKER BISPHAM, Solicitor. MANAGERS. EFFINGHAM B. MORRIS, WILLIAM H. -

Bankers and Trust Section, Vol. 81, No. 2104

tttannal SECTION. CONTAINING REPORT OF THE CONVENTION OF AMERICAN BANKERS' ASSOCIATION Held at WASHINGTON, OCT. JO, tt, 12 and 13, 1905 INDEX TO THIS SECTION: Page. Page. EDITORIAL ARTICLES- BANKING SECTION- CONVENTION AND CURRENCY - - 73 PROTECTIVE COMMITTEE - - - 104 THE CONVENTION'S WORK - - 74 COMMITTEE ON UNIFORM LAWS 105 THE TRUST COMPANY SECTION - 76 REPORT EXECUTIVE COUNCIL - 106 THE SAVINGS BANK SECTION - 77 COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION - - 112 BANKING SECTION- REPORT CURRENCY COMMITTEE 116 TRADE EXPANSION—SHAW - - 81 REPORT ON CIPHER CODE - - - 117 BANK EXAMINATION—RIDGELY - 84 AUDITING COMMITTEE REPORT - 123 SCOTCH BANKING—BLYTH - - - 87 TRUST COMPANY SECTION- OUR COMMERCE—GOULDER - - 90 TRUST COMPANY GROWTH - - - 127 THE SITUATION—VANDERLIP - - 94 BANKING PUBLICITY 129 MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS—HILL - 97 REAL ESTATE DEPARTMENT - - 130 DETAILED PROCEEDINGS - - - 99 DETAILED PROCEEDINGS - - - 133 ADDRESSES OF WELCOME - - - 99 SAVINGS BANK SECTION- PREST. SWINNEY'S ADDRESS - - 101 OHIO BANK LEGISLATION - - - 142 IN - - - 145 REPORT OF SECRETARY - - - 103 ACCOUNTS TWO NAMES DETAILED PROCEEDINGS - - - 148 REPORT OF TREASURER - - - - 104 For Index to Advertisements, see pages 79 and 80 Octolber 217 ISO©. CSEMESa WILLIAM B. DANA COMPANY, PUBLISHERS. PINE STREET, corner PEARL STREET, NEW YORK. Entered according to Act of Congress in year 1905, by William B. Dana Company, in office of Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C. Chartered 1836 GIRARD TRUST COMPANY PHILADELPHIA, PA. CAPITAL, $2,500,000 SURPLUS, $7,500,000 Acts as Trustee of Corporation Mortgages, Acts as Executor, Administrator, Trustee, Registrar and Transfer Agent. Assignee and Receiver. Assumes Entire Charge of Real Estate. Depositary under Plans of Reorganization. Interest Allowed on Individual and Corpo- Financial Agent for Individuals or ration Accounts. -

September 23, 1905, Vol. 81, No. 2100

. 1 1; 5 financial nmicle INCLUDING Bank and Quotation Section (Monthly) State and City Section (semi-Annually ) Railway and Industrial Section ^Quarterly) Street Railway Section ee (^Jf ) Entoroii according to Aot of Congrass, in the year 1005, by WILLIAM 1?. Dana Company, in the otttce of librarian of Congress, Washington, I). C. A weekly nomMMr entered at Host office. New York, ai second-clam mutter— w ii.liam B. Dana Company, Publishers. 7B}< Pine St,, N. Y. VOL. 81 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 1905. NO. 2100. II ee/: enduuj Sept. 10 Clearing* o.t Inc. or %\xt (Chronicle. 1905. 1904. Dec 1903. 1902 PUBLISHED WEEKLY. +17-7 ol Subscription—Payable in Advance Boston 139,943.741 118.938,?!)! 121.342.251 120,391.923 Terms I'rovidence 6,508,000 6,181 ."I") +53 6.980,100 6.4*5,000 For One iear $10 00 Ilurtford 3, nao. Ton 2,441.705 --240 2.208.660 2,881.665 --20-2 J/or 8is Months 6 Oil New Haven- 8,824,208 1,860,377 l.6i 1.740,962 - -13-8 >o turopean .-ubscnption (including postage) 13 oo Spnmrfleld 1.741.H44 1.580,443 1 1-7,016 1,280,6 --10 European 6UbscripUon Six Months (including postage) 7 50 Worcester 1,444,460 1,302,007 9 1 483.294 1.598,275 Portland 1,770,630 1,624.902 +8 4 I £03,884 1.842.551 Annual Subscription in London (including postage) £2 14s. Fall Kiver 799.1147 546.960 +353 770,614 902,228 6n Months Subscription in London (including postage) £1 lis.