The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16Pf Protective Services Report Candidate’S Personality Impacts His/Her Work Style and Job Performance

16pf® Protective Services Report 16pf® Protective Services Report Plus Key Features & Benefits Both the 16pf PSR and the 16pf PSR+ help you quickly identify which candidates to move forward in the selection process by examining how a 16pf Protective Services Report candidate’s personality impacts his/her work style and job performance. Suitable for both pre- and post-offer Both reports deliver: selection. • An in-depth normal personality assessment; • Scores on our proprietary, research-based 16pf Protective Services Helps identify individuals who can: Dimensions. Cope with stress and respond appropriately under pressure; Work responsibly and ethically; 16pf PSR Dimension Proven to Predict Problem-solve and make sound decisions; Emotional Adjustment Training Success Peer Approval Communicate effectively with co- How an individual adjusts to workers and the public. challenging situations, such Positive Work Behaviors Presents insights into the individual’s as remaining calm and acting Terminations appropriately in uncertain or thought patterns, beliefs, and Reprimands stressful situations. behaviors. Job Knowledge Based on comprehensive research with police, corrections, and military Integrity/Control Terminations personnel, making both reports Whether the individual is likely to Successful Hires job-relevant for protective services act in a dependable, conscientious positions. and self-controlled manner. Grounded in universally-accepted normal personality theory. Intellectual Efficiency Training Success Administered and scored locally or The respondent’s typical style of Job-specific Knowledge available via the Internet. decision making and his/her ability Terminations to evaluate situations and quickly Successful Hires 16pf Protective Services generate solutions. Report Plus Provides all of the above benefits plus: Interpersonal Relations Training Success A comprehensive picture of the Peer Acceptance Reveals the individual’s manner candidate – normal personality plus of relating to others and typical Terminations his/her psychological functioning. -

All in the Mind Psychology for the Curious

All in the Mind Psychology for the Curious Third Edition Adrian Furnham and Dimitrios Tsivrikos www.ebook3000.com This third edition first published 2017 © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Edition history: Whurr Publishers Ltd (1e, 1996); Whurr Publishers Ltd (2e, 2001) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of Adrian Furnham and Dimitrios Tsivrikos to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Intelligence : Its Structure, Growth and Action

INTELLIGENCE : ITS STRUCTURE, GROWTH AND ACTION Raymond B. CATTELL Cattell Institute, Hawaii 1987 NORTH-HOLLAND AMSTERDAM . NEW YORK ' OXFORD . TOKYO @ ELSEVIER SCIENCE PUBLISHERS B.V., 1987 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any way, form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN : 0 444 87922 6 Publishers: ELSEVIER SCIENCE PUBLISHERS B.V. P.O.Box 1991 1000 BZ Amsterdam The Netherlands Sole distributors for the U.S.A. and Canada: ELSEVIER SCIENCE PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC. 52 Vanderbilt Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 U.S.A. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cattell, Raymond B. (Raymond Bernard), 1905- Intelligence: its structure, growth, and action. (Advances in psychology ; 35) Rev. ed. of: Abilities: their structure, growth, and action. 1971. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Intellect. 2. Ability. I. Cattell, Raymond B. (Raymond Bernard), 1905- . Abilities: .their struc- ture, growth, and action. 11. Title. 111. Series: Advances in psychology (Amsterdam, Netherlands) ; 35. BF431.C345 1986 153.9 86-16606 ISBN 0-444-87922-6 (U.S.) PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS FOREWORD The nature and measurement of man’s abilities as a central pre- occupation of psychology had its day in the closing years of the last century and in the early decades of the present one. Unfortunately, the enterprise faltered, and interest declined as other aspects of psychology became more fashionable. Perhaps it is not entirely fair to say that interest in abilities went out of style but rather that the field stagnated, suffering from a paucity of new ideas and characterized by the persis- tence of out-moded concepts. -

Essentials of 16PF Assessment / Heather Cattell, James M

Essentials of 16PF ® Assessment Heather E. P.Cattell James M. Schuerger John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Essentials of 16PF® Assessment Essentials of Psychological Assessment Series Series Editors, Alan S. Kaufman and Nadeen L. Kaufman Essentials of WAIS-III® Assessment Essentials of Individual Achievement by Alan S. Kaufman and Elizabeth O. Assessment Lichtenberger by Douglas K. Smith Essentials of CAS Assessment Essentials of TAT and Other Storytelling by Jack A. Naglieri Techniques Assessment by Hedwig Teglasi Essentials of Forensic Psychological Assessment by Marc J. Ackerman Essentials of WJ III® Tests of Achievement Assessment Essentials of Bayley Scales of Infant by Nancy Mather, Barbara J. Wendling, and Development-II Assessment Richard W. Woodcock by Maureen M. Black and Kathleen Matula Essentials of WJ III® Cognitive Abilities ® Essentials of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Assessment Assessment by Fredrick A. Schrank, Dawn P. Flanagan, by Naomi Quenk Richard W. Woodcock, and Jennifer T. Essentials of WISC-III® and WPPSI-R® Mascolo Assessment Essentials of WMS®-III Assessment by Alan S. Kaufman and Elizabeth O. by Elizabeth O. Lichtenberger, Alan S. Lichtenberger Kaufman, and Zona Lai Essentials of Rorschach® Assessment Essentials of MMPI-A™ Assessment by Tara Rose, Nancy Kaser-Boyd, and by Robert P. Archer and Radhika Michael P. Maloney Krishnamurthy Essentials of Career Interest Assessment Essentials of Neuropsychological Assessment by Jeffrey P. Prince and Lisa J. Heiser by Nancy Hebben and William Millberg Essentials of Cross-Battery Assessment Essentials of Behavioral Assessment by Dawn P. Flanagan and Samuel O. Ortiz by Michael C. Ramsay, Cecil R. Reynolds, Essentials of Cognitive Assessment with KAIT and R.W. -

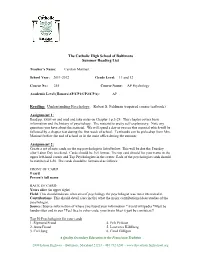

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

Introduction to Political Psychology

INTRODUCTION TO POLITICAL PSYCHOLOGY This comprehensive, user-friendly textbook on political psychology explores the psychological origins of political behavior. The authors introduce read- ers to a broad range of theories, concepts, and case studies of political activ- ity. The book also examines patterns of political behavior in such areas as leadership, group behavior, voting, race, nationalism, terrorism, and war. It explores some of the most horrific things people do to each other, as well as how to prevent and resolve conflict—and how to recover from it. This volume contains numerous features to enhance understanding, includ- ing text boxes highlighting current and historical events to help students make connections between the world around them and the concepts they are learning. Different research methodologies used in the discipline are employed, such as experimentation and content analysis. This third edition of the book has two new chapters on media and social movements. This accessible and engaging textbook is suitable as a primary text for upper- level courses in political psychology, political behavior, and related fields, including policymaking. Martha L. Cottam (Ph.D., UCLA) is a Professor of Political Science at Washington State University. She specializes in political psychology, inter- national politics, and intercommunal conflict. She has published books and articles on US foreign policy, decision making, nationalism, and Latin American politics. Elena Mastors (Ph.D., Washington State University) is Vice President and Dean of Applied Research at the American Public University System. Prior to that, she was an Associate Professor at the Naval War College and held senior intelligence and policy positions in the Department of Defense. -

Factor-Analytic Trait Theories: Raymond Cattell, the Big Five Model Module Tag PSY P5 M3

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Subject PSYCHOLOGY Paper No and Title Paper No 5: Personality Theories Module No and Title Module No 3: Factor-analytic trait theories: Raymond Cattell, The Big Five Model Module Tag PSY_P5_M3 Table of Contents 1. Learning Outcomes 2. Introduction 3. Raymond Cattell and his Approach to Personality 3.1 Biographical Account 3.2 Cattell’s Approach to Personality 3.3 Assessment in Cattell’s Theory 4. The Big Five Model 4.1 Robert R. McCrae and Paul T. Costa, Jr.: Biographical Accounts 4.2 Searching for the Big Five 4.3 Five-Factor Theory: Units 5. Evaluative Comments 6. Summary PSYCHOLOGY Paper No 5: Personality Theories Module No 3: Factor-analytic trait theories: Raymond Cattell, The Big Five Model ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to Reflect on Factor Analytic Theories and Factor Analysis Review the Cattellian Approach to Personality Review the Big Five Model of Personality Evaluate Factor Analytic Theories 2. Introduction Nomothetic trait models are obligated to Raymond Cattell, an eloquent proponent that key attributes of personality can be illustrated by discrete dimensions. Cattell’s theory of personality is inseparably connected to quantitative measurement models based on factor analysis of personality data through questionnaire responses and other sources. While Costa and McCrae attempted to stimulate the majestic proposal of Cattell’s idea- an empirical model of traits encompassing gamut of personality. Their Big Five model was focused on depiction of personality, not causes of personality. To study problems with multiple variables, Cattell stressed a great deal on the statistical tool of factor analysis which is used to segregate larger group of observed, interrelated variables to find out a limited number of underlying factors. -

A Conjectural History of Cambridge Analytica's Eugenic Roots

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0505-5 OPEN Sordid genealogies: a conjectural history of Cambridge Analytica’s eugenic roots ✉ Michael Wintroub1 “Sordid Genealogies: A Conjectural History of Cambridge Analytica’s Eugenic Roots” explores the history of the methods employed by Cambridge Analytica to influence the 2016 US presidential election. It focuses on the history of psychometric analysis, trait psychology, the 1234567890():,; lexical hypothesis and multivariate factor analysis, and how they developed in close con- junction with the history of eugenics. More particularly, it will analyze how the work of Francis Galton, Ludwig Klages, Charles Spearman, and Raymond Cattell (among others) contributed to the manifold translations between statistics, the pseudoscience of eugenics, the politics of Trumpism, and the data driven psychology of the personality championed by Cambridge Analytica. 1 University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. ✉email: [email protected] HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2020) 7:41 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0505-5 1 ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0505-5 translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew to Greek, they Once King Ptolemy gathered seventy-two elders and put might, in the same breath, have contested the veracity of its them into seventy-two houses, and did not reveal to them content. why he gathered them. He entered each room and said to “ ” Similar conundrums have troubled the ways we have thought them: Write the Torah of Moses your rabbi for me . The about translation since the invention of fiction as a genre in the Holy One, blessed by He gave counsel into each of their early modern period. -

AP Psychology Ch. 8 Study Guide – Cognition: Thinking, Intelligence and Language

AP Psychology Ch. 8 Study Guide – Cognition: Thinking, Intelligence and Language 1. Not being able to notice that pliers could be used as a weight when tied to a string and used to swing the string toward you like a pendulum is an example of: _____________ 2. Define functional fixedness. 3. The tendency for people to persist in using problem-solving patterns that have worked for them in the past is known as ________________________. 4. Define intelligence. 5. The "g" in Spearman's g factor of intelligence stands for ______________________. 6. Know Gardner’s 9 multiple intelligences 7. Sternberg has found that _______________________ intelligence is a good predictor of success in life but has a low relationship to _______________________ intelligence. 8. What three types of intelligence constitute Sternberg's triarchic theory of intelligence? 9. If a test consistently produces the same score when administered to the same person under identical conditions, that test can be said to be high in ______________________. 10. Which aspects are included in the definition of intellectual disability? 11. Brush up on the nature vs. nurture debate. 12. Define language. 13. The basic units of sound are called ______________________. 14. What is syntax? 15. If someone's IQ score is in the 97th percentile, what is their IQ likely to be? 16. The tendency of young children learning language to overuse the rules of syntax is referred to as 17. Tristan, a seven-year-old male, has an IQ of 128. Tristan's mental age is ______? 18. Alfred Binet was primarily concerned with (what did his work consist of)? 19. -

The Cross-Cultural Comparability of the 16 Personality Factor Inventory (16Pf) Fatima Abrahams

THE CROSS-CULTURAL COMPARABILITY OF THE 16 PERSONALITY FACTOR INVENTORY (16PF) FATIMA ABRAHAMS THE CROSS-CULTURAL COMPARABILITY OF TIIE 16 PERSONALITY FACTOR INVENTORY (16PF) by FATIMA ABRAHAMS submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF COMMERCE in the subject INDUSTRIAL PSYCHOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF K F MAUER 30 NOVEMBER 1996 IBIS IBESIS IS DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS, ACHMAT AND WARALDIA GYDIEN, MY HUSBAND, RAMZIE AND MY DAUGHTERS, ZAREEN AND MISHKAH. UN ISA BIBUOTEEK I LIBRARY rn~d-04- , 1 Class Klas .. 155. 283 ABRA Ace es Aanwi1 ...... llHHlmHllll 0001698820 Student number: 3004-475-8 I declare that The cross-cultural comparability of the 16 Personality Factor Inventory (16PF) is my own work and all that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. SIGNATURE DATE (MRS) F ABRAHAMS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praises are due to the Creator who granted me the ability to tackle and complete this thesis. I would also like to thank all the people who supported me throughout the process, particularly: Prof. K F Mauer, my supervisor, for his suggestions and inputs about the thesis in general, his critical comments of the draft chapters, and his constant willingness to support me throughout the entire process. Prof. Micheal Muller and Ms. Evelyn Muller for their advice and help with conducting the statistical analysis. My brother Ziyaad, for his continual support and for acting as my research assistant, who spent many hours coding and punching the data. The staff of the Psychology and/or Industrial Psychology Departments at the University of Durban-Westville, University of Pretoria, and University of Natal who so willingly spent time helping me with the administration of the test. -

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY of PSYCHOLOGY

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Irving B. Weiner John Wiley & Sons, Inc. HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY VOLUME 1 HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Volume Editor Irving B. Weiner Editor-in-Chief John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. ➇ Copyright © 2003 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

16PF® Psychological Evaluation Report

16PF® Psychological Evaluation Report The 16PF PER screens for twelve When evaluating an individual’s fitness for duty, a complete pathology-oriented behavioral personality picture is essential. The 16PF PER is uniquely qualified characteristics and delivers in-depth to do this as it is generated from the 16PF Psychological Evaluation normal personality information. In Questionnaire, a combination of the 16PF Questionnaire (a normal fitness-for-duty evaluations, this personality assessment) and an additional 140 items that screen for saves valuable time and money psychopathology. over longer, single-focus, invasive assessments. A Deeper Look at Depression The 16PF PER assists in the evaluation of overall functioning, including Key Features & Benefits documentation of the reported presence of symptoms of depression. The unique, multi-dimensional structure Over half of the test’s clinical scales assess a facet of depression, a of the 16PF PER gives you: common yet difficult-to-identify diagnosis for individuals in high-risk occupations. In addition, a composite scale, Depressive Characteristics, Useful normal personality insights, includes these six scales: Health Concerns, Suicidal Thinking, Anxious even if pathology is not present. Depression, Low Energy, Self-Reproach, and Apathetic Withdrawal. Narrative interpretation of every elevated scale on both the normal and clinical scales. Three scales that measure the individual’s attitude toward the test taking process. A QuickEval Index for an instant indication of the person’s overall feeling of adequacy, self-worth, and their ability to cope. Three additional indices which signal whether further evaluation is needed in the areas of depression, distorted thoughts, and risk-taking behaviors. Occupational areas the individual may be drawn to, based upon his/her unique personality.