Miscegenation: the Courts and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness. -

What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol

Hofstra Law Review Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 22 2004 Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti- Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 32: Iss. 4, Article 22. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol32/iss4/22 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tel LOVE WITH A PROPER STRANGER: WHAT ANTI-MISCEGENATION LAWS CAN TELL US ABOUT THE MEANING OF RACE, SEX, AND MARRIAGE Rachel F. Moran* True love. Is it really necessary? Tact and common sense tell us to pass over it in silence, like a scandal in Life's highest circles. Perfectly good children are born without its help. It couldn't populate the planet in a million years, it comes along so rarely. -Wislawa Szymborskal If true love is for the lucky few, then for the rest of us there is the far more mundane institution of marriage. Traditionally, love has sat in an uneasy relationship to marriage, and only in the last century has romantic love emerged as the primary, if not exclusive, justification for a wedding in the United States. -

Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by Or About Asian Latin Americans

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 26 September 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0506.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Humanities 2018, 7, 110; doi:10.3390/h7040110 Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by or About Asian Latin Americans Ignacio López-Calvo University of California, Merced [email protected] Abstract This essay studies Afro-Asian sociocultural interactions in cultural production by or about Asian Latin Americans, with an emphasis on Cuba and Brazil. Among the recurrent characters are the black slave, the china mulata, or the black ally who expresses sympathy or even marries the Asian character. This reflects a common history of bondage shared by black slaves, Chinese coolies, and Japanese indentured workers, as well as a common history of marronage.1 These conflicts and alliances between Asians and blacks contest the official discourse of mestizaje (Spanish-indigenous dichotomies in Mexico and Andean countries, for example, or black and white binaries in Brazil and the Caribbean), which, under the guise of incorporating the Other, favored whiteness, all the while attempting to silence, ignore, or ultimately erase their worldviews and cultures. Keywords: Afro-Asian interactions, Asian Latin American literature and characters, Sanfancón, china mulata, “magical negro,” chinos mambises, Brazil, Cuba, transculturation, discourse of mestizaje Among the recurrent characters in literature by or about Asians in Latin America are the black slave, the china mulata, or the -

The Making of a Eurasian: Writing, Miscegenation, and Redemption in Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton by Juanita C

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies 3 (2012) 14-26. The Making of a Eurasian: Writing, Miscegenation, and Redemption in Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton by Juanita C. But I have come from a race on my mother’s side which is said to be the most stolid and insensible to feeling of all races, yet I look back over the years and see myself so keenly alive to every shade of sorrow and suffering that is almost pain to live. Fundamentally, I muse, all people are the same. My mother’s race is as prejudiced as my father’s. Sui Sin Far/Edith Maude Eaton1 If there is one persistent struggle that exists in the life of Edith Eaton, also known as Sui Sin Far, it is the coming to terms with her racial identity/identities in an environment of prejudice and intolerance. This lifelong struggle has become the enduring impetus for her writing; it is her intention to create a discursive space for a territory of issues, thoughts, and experiences that remain otherwise repressed in open discussions. There is no doubt that the rough terrain of race relations does not emerge only in her generation. Amidst the numerous discourses advocating segregation and hostility between races in the prolonged history of racism in America—the discriminatory agenda of which was further intensified by the extreme Sinophobia during the late 1800s—she felt the exigency to present an honest and sympathetic account of a group of Chinese immigrants who find themselves in situations of racial strife in a society of different values and tradition. -

Scientific Racism and the Legal Prohibitions Against Miscegenation

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 5 2000 Blood Will Tell: Scientific Racism and the Legal Prohibitions Against Miscegenation Keith E. Sealing John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Race Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Keith E. Sealing, Blood Will Tell: Scientific Racism and the Legal Prohibitions Against Miscegenation, 5 MICH. J. RACE & L. 559 (2000). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol5/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLOOD WILL TELL: SCIENTIFIC RACISM AND THE LEGAL PROHIBITIONS AGAINST MISCEGENATION Keith E. Sealing* INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 560 I. THE PARADIGM ............................................................................ 565 A. The Conceptual Framework ................................ 565 B. The Legal Argument ........................................................... 569 C. Because The Bible Tells Me So .............................................. 571 D. The Concept of "Race". ...................................................... 574 II. -

The Yellow Pacific: Transnational Identities, Diasporic Racialization, and Myth(S) of the “Asian Century”

The Yellow Pacific: Transnational Identities, Diasporic Racialization, and Myth(s) of the “Asian Century” Keith Aoki* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 899 I. THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AS THE ASIAN CENTURY: IS THERE A “THERE” THERE? .................................................... 902 II. FEAR OF A “YELLOW” PLANET: WAS THE TWENTIETH CENTURY THE “ASIAN CENTURY”? ............................................ 907 A. Prelude to the Asian Century: Harsh Nineteenth and Early- to Mid-Twentieth Century Immigration Policies Towards Asian Immigrants ................................................ 912 B. The Gentleman’s Agreement of 1906–1907 and California’s Alien Land Laws ............................................. 917 C. The Japanese American Internment .................................... 927 III. HAVE WE MET THE “OTHERS” AND ARE “WE” THEY (OR ARE “THEY” US)? ............................................................................. 935 A. Diaspora: The Ocean Flows Both Ways (Why Do You Have to Fly West to Get East?) .......................................... 936 B. Defining and Redefining Diaspora: Changing Scholarly Perspectives ....................................................................... 938 C. Diaspora(s) Today: From Assimilation to Exotification and Back Again ................................................................. 944 IV. A WORLD AFLAME, OR IS THE SKY REALLY FALLING? ................ 947 A. “Free” Markets and “Raw” Democracy = -

Diaspora, Law and Literature Law & Literature

Diaspora, Law and Literature Law & Literature Edited by Daniela Carpi and Klaus Stierstorfer Volume 12 Diaspora, Law and Literature Edited by Daniela Carpi and Klaus Stierstorfer An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-048541-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-048925-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048821-0 ISSN 2191-8457 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents DanielaCarpi Foreword VII Klaus Stierstorfer Introduction: Exploringthe InterfaceofDiaspora, Law and Literature 1 Pier Giuseppe Monateri Diaspora, the West and the Law The Birth of Christian Literaturethrough the LettersofPaul as the End of Diaspora 7 Riccardo Baldissone -

Marrying out One-In-Seven New U.S

Marrying Out One-in-Seven New U.S. Marriages is Interracial or Interethnic RELEASED JUNE 4, 2010; REVISED JUNE15,2010 Paul Taylor, Project Director Jeffrey S. Passel, Senior Demographer Wendy Wang, Research Associate Jocelyn Kiley, Research Associate Gabriel Velasco, Research Analyst Daniel Dockterman, Research Assistant MEDIA INQUIRIES CONTACT: Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project 202.419.4372 http://pewsocialtrends.org ii Marrying Out One-in-Seven New U.S. Marriages Is Interracial or Interethnic By Jeffrey S. Passel, Wendy Wang and Paul Taylor Executive Summary This report is based primarily on two data sources: the Pew Research Center’s analysis of demographic data about new marriages in 2008 from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) and the Pew Research Center’s analysis of its own data from a nationwide telephone survey conducted from October 28 through November 30, 2009 among a nationally representative sample of 2,884 adults. For more information about data sources and methodology, see page 31. Key findings: A record 14.6% of all new marriages in the United States in 2008 were between spouses of a different race or ethnicity from one another. This includes marriages between a Hispanic and non- Hispanic (Hispanics are an ethnic group, not a race) as well as marriages between spouses of different races – be they white, black, Asian, American Indian or those who identify as being of multiple races or ―some other‖ race. Among all newlyweds in 2008, 9% of whites, 16% of blacks, 26% of Hispanics and 31% of Asians married someone whose race or ethnicity was different from their own. -

Mixed Race Capital: Cultural Producers and Asian American Mixed Race Identity from the Late Nineteenth to Twentieth Century

MIXED RACE CAPITAL: CULTURAL PRODUCERS AND ASIAN AMERICAN MIXED RACE IDENTITY FROM THE LATE NINETEENTH TO TWENTIETH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Stacy Nojima Dissertation Committee: Vernadette V. Gonzalez, Chairperson Mari Yoshihara Elizabeth Colwill Brandy Nālani McDougall Ruth Hsu Keywords: Mixed Race, Asian American Culture, Merle Oberon, Sadakichi Hartmann, Winnifred Eaton, Bardu Ali Acknowledgements This dissertation was a journey that was nurtured and supported by several people. I would first like to thank my dissertation chair and mentor Vernadette Gonzalez, who challenged me to think more deeply and was able to encompass both compassion and force when life got in the way of writing. Thank you does not suffice for the amount of time, advice, and guidance she invested in me. I want to thank Mari Yoshihara and Elizabeth Colwill who offered feedback on multiple chapter drafts. Brandy Nālani McDougall always posited thoughtful questions that challenged me to see my project at various angles, and Ruth Hsu’s mentorship and course on Asian American literature helped to foster my early dissertation ideas. Along the way, I received invaluable assistance from the archive librarians at the University of Riverside, University of Calgary, and the Margaret Herrick Library in the Beverly Hills Motion Picture Museum. I am indebted to American Studies Department at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa for its support including the professors from whom I had the privilege of taking classes and shaping early iterations of my dissertation and the staff who shepherded me through the process and paperwork. -

Settler Colonialism As Structure

SREXXX10.1177/2332649214560440Sociology of Race and EthnicityGlenn 560440research-article2014 Current (and Future) Theoretical Debates in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2015, Vol. 1(1) 54 –74 Settler Colonialism as © American Sociological Association 2014 DOI: 10.1177/2332649214560440 Structure: A Framework for sre.sagepub.com Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation Evelyn Nakano Glenn1 Abstract Understanding settler colonialism as an ongoing structure rather than a past historical event serves as the basis for an historically grounded and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender formation. The settler goal of seizing and establishing property rights over land and resources required the removal of indigenes, which was accomplished by various forms of direct and indirect violence, including militarized genocide. Settlers sought to control space, resources, and people not only by occupying land but also by establishing an exclusionary private property regime and coercive labor systems, including chattel slavery to work the land, extract resources, and build infrastructure. I examine the various ways in which the development of a white settler U.S. state and political economy shaped the race and gender formation of whites, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Chinese Americans. Keywords settler colonialism, decolonization, race, gender, genocide, white supremacy In this article I argue for the necessity of a settler to fight racial injustice. Equally, I wish to avoid colonialism framework for an historically grounded seeing racisms affecting various groups as com- and inclusive analysis of U.S. race and gender for- pletely separate and unrelated. Rather, I endeavor mation. A settler colonialism framework can to uncover some of the articulations among differ- encompass the specificities of racisms and sexisms ent racisms that would suggest more effective affecting different racialized groups—especially bases for cross-group alliances. -

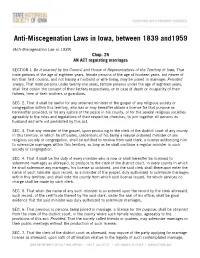

Full Transcript of Anti-Miscegenation Laws in Iowa

Anti-Miscegenation Laws in Iowa, between 1839 and1959 (Anti-Miscegenation Law in 1839) Chap. 25 AN ACT regulating marriages SECTION I. Be it enacted by the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of Iowa, That male persons of the age of eighteen years, female persons of the age of fourteen years, not nearer of kin than first cousins, and not having a husband or wife living, may be joined in marriage: Provided always, That male persons under twenty-one years, female persons under the age of eighteen years, shall first obtain the consent of their fathers respectively, or in case of death or incapacity of their fathers, then of their mothers or guardians. SEC. 2. That it shall be lawful for any ordained minister of the gospel of any religious society or congregation within this territory, who has or may hereafter obtain a license for that purpose as hereinafter provided, or for any justice of the peace in his county, or for the several religious societies agreeably to the rules and regulations of their respective churches, to join together all persons as husband and wife not prohibited by this act. SEC. 3. That any minister of the gospel, upon producing to the clerk of the district court of any county in this territory, in which he officiates, credentials of his being a regular ordained minister of any religious society or congregation, shall be entitled to receive from said clerk, a license authorizing him to solemnize marriages within this territory, so long as he shall continue a regular minister in such society or congregation.