Community Lending Plan 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Users\Joemo\Documents\Old School Material\Black Knights

THE BLACK KNIGHT’S REVENGE AN OSRIC ADVENTURE BY JOSEPH A. MOHR © OldSample School Role file Playing OLD SCHOOL ROLE PLAYING What is Old School Role Playing about? At Old School we are all about the classic version of role playing games that were popular in the late 1970s to the early 1980s. You know the games. You played them as kids. They were far better than many of the later versions that came along. At Old School we bring you high quality adventures and adventure products for gaming at a reasonable price. The adventures themselves are well thought out. They have a few puzzles, riddles and other encounters as well as plenty of monster bashing action. Some have been thoroughly play tested by other gamers. The goal is to provide you the game master adventures to use on the spur of the moment when players want to play and you do not have the time to prepare something spectacular. Joseph A. Mohr Sample file CREDITS The Black Knight’s Revenge is written by Joseph A. Mohr Cartography was made with Campaign Cartographer 2 Pro by Joseph A. Mohr. Artwork included on the cover page and interior of this adventure were created by: Altar [email protected] Black Armor Statue Rajat Prajapati Banshee [email protected] Birdcage [email protected] Black Knight [email protected] Black Knight Dover Clipart Black Knight’s Body Guards Dover Clipart Castle Ruins [email protected] Castle Ruins [email protected] Dragon Statue [email protected] Fountain of Good and -

Mourning, Melancholia, and Masculinity in Medieval Literature Rebekah Mary Fowler Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2011 Mourning, Melancholia, and Masculinity in Medieval Literature Rebekah Mary Fowler Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Fowler, Rebekah Mary, "Mourning, Melancholia, and Masculinity in Medieval Literature" (2011). Dissertations. 336. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/336 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOURNING, MELANCHOLIA, AND MASCULINITY IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE by Rebekah M. Fowler B.S., Illinois State University, 1988 M. A. University of Illinois at Springfield, 2005 Ph.D., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2011 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May, 2011 DISSERTATION APPROVAL MOURNING, MELANCHOLIA, AND MASCULINITY IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE By Rebekah M. Fowler A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Ryan Netzley, Chair Mary Ellen Lamb Dan Wiley Elizabeth Klaver Gerard Delahoussaye Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale January 27, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF REBEKAH M. FOWLER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in English, presented on JANUARY 27, 2011, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: MOURNING, MELANCHOLIA, AND MASCULINITY IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Character Job Level Get Skill Role Swordsman 16 Fireball II 30

Characters: Level up Change jobs Character Memo name hp mp atk def agi hp mp atk def agi Swordsman 11 4 6 5 3 0 0 0 0 0 Swordsmaster 20 10 9 14 3 20 10 9 14 3 Role Juggernaut 14 7 13 8 3 14 7 13 8 3 Hero 20 18 18 13 4 20 18 18 13 4 Stage 13 get Priest 10 6 6 4 2 0 0 0 0 0 Aileen Chaplain 17 10 9 10 2 17 10 9 10 2 Monk 15 15 13 8 2 15 15 13 8 2 Knight 13 4 7 5 2 0 0 0 0 0 Ray Paladin 18 9 11 13 3 18 9 11 13 3 Black Knight 20 4 16 10 3 20 4 16 10 3 Magician 9 10 4 4 3 0 0 0 0 0 Sasa Magister 16 16 6 10 3 16 16 6 10 3 Wizard 12 16 12 9 2 12 16 12 9 2 Warrior 16 4 11 6 2 0 0 0 0 0 Qiqi Berzerker 24 4 22 10 2 22 4 22 10 2 Gladiator 18 6 16 16 2 18 6 16 16 2 Magician 8 10 6 6 4 0 0 0 0 0 Jojo Magister 12 11 7 10 2 12 11 7 10 2 Wizard 14 17 10 14 3 14 17 10 14 3 Engineer 11 5 6 5 3 0 0 0 0 0 Jingle Craftsman 17 6 10 10 3 17 6 10 10 3 Sharpshooter 15 12 15 8 3 15 12 15 8 3 Aircraft 15 5 9 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 Zero Aircraft 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 30 30 0 Stage 16 get Aircraft 0 0 0 0 0 100 0 0 0 0 Stage 21 get Wolf Pack Elder 15 4 17 9 4 15 4 17 9 4 Nightingale Marksman 18 6 13 10 3 18 6 13 10 3 Meryl Paladin 16 0 16 16 4 0 0 0 0 0 Nie Magister 14 14 8 8 5 0 0 0 0 0 Skills that can be learned in role profession: Character Job Level Get skill 16 Fireball II Swordsman 30 Fireball III Swordsmaster 8 Fireball IV 8 Glorious Reposte Role Juggernaut 15 Fireball IV 3 Glorious Reposte Hero 6 Heal III 10 Fireball IV Destruction of the 20 Earth 1 Heal I 10 Mute Priest 16 Heal II 18 Heal III 5 Recovery Chaplain Aileen 10 Heal IV 2 Holy Light I 10 God's Blessing Monk 15 Heal -

The Black Range, 05-04-1883

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Black Range, 1882-1897 (Socorro County) New Mexico Historical Newspapers 5-4-1883 The lB ack Range, 05-04-1883 Black Range Print Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/black_range_news Recommended Citation Black Range Print Co.. "The lB ack Range, 05-04-1883." (1883). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/black_range_news/319 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Range, 1882-1897 (Socorro County) by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'ft-- JLJ f DEVOTED TO THE MINING INTERESTS OF THE BLACK RANGE COUNTRY. VOL. II. CHLORIDE, SOCORRO COUNTY, N. M., FRIDAY, MAY 4, 1883. NO. 4. MEW TO MEN TO PATRONIZE. FATKONIZK. y NEWS AND COMMENTS. BLACK RANGE MINES. mainder is being brought down as rap-Idl- rocks, is no way detrimental to the cy C.W. Fox, D. H.Wcngkk, as possible. As soon as the ore and valne of the property. toa. can Socorro. Oral Ileavy rains are doing much damage An Unprejudiced Opinion Con- be all brought down.it will be Tbe mineral currents which deposited HERLOW'S HOTEL, to railroads and. farms in North Caro freighted to Engle and a shipment of the ore, have invaribably left well de- Fox & Wenger, . cerning Some of them lina and Georgia. several car loads inado.-whlc- h it is an- fined traces of their passages, and the Counselors-at-Law- , ticipated will run $300 to the ton. -

Confronting the Holocaust in Philip Kerr's Bernie Gunther Novels

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 38.1 (June 2016): 89-107 issn 0210-6124 “But What’s One More Murder?” Confronting the Holocaust in Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther Novels Anthony Lake Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates [email protected] Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther series of Nazi Germany-set historical crime novels use irony in the exploration of themes of complicity, guilt and redemption in relation to the Holocaust. The use of irony enables Kerr’s protagonist Bernie Gunther to confront and describe the Holocaust and establish his sense of selfhood as an anti-Nazi. However, it does not empower him to resist the Nazis actively. Bernie seeks to confront the Holocaust and describe his experiences as an unwilling Holocaust perpetrator when he led an SS police battalion at Minsk in 1941. Later, his feelings of guilt at his complicity with the Nazis in the Holocaust haunt him, and he seeks redemption by pursuing justice to solve conventional murders. The redemption that Bernie Gunther pursues is called into question in the ninth novel in the series, A Man Without Breath (2013), when the possibility of active resistance to the Nazis is revealed to him when he witnesses the Rosenstrasse Protests in Berlin in 1943. This revelation raises the questions of agency and choice, and forces an ordinary German like Bernie Gunther to confront the possibility that he might have actively opposed the Nazis, rather than allow himself to become their accomplice. Keywords: detective fiction; Holocaust; Philip Kerr; irony; guilt; redemption . “¿Qué supone un asesinato más?” Afrontando el Holocausto en las novelas de Philip Kerr sobre Bernie Gunther En las novelas policiacas de Philip Kerr sobre Bernie Gunther, ambientadas en la Alemania Nazi, el autor recurre con frecuencia a la ironía para explorar temas como la complicidad, la culpa o la redención en relación con el Holocausto. -

A Gallery of Archetypes

Meta Religion / Psychiatry / Analytical Psychology / (from http://www.meta-religion.com/Psychiatry/Analytical_psychology/a_gallery_of_archetypes.htm) A Gallery of Archetypes From: http://www.myss.com/ThreeArchs.asp The archetypes listed here in boldface type are just a few of the many ancient patterns that exist in human consciousness. Many additional archetypes that are closely related are mentioned in parentheses, such as Hermit (found under Mystic), Therapist (under Healer), or Pirate (under Rebel). Please read through the entire list, looking at all the archetypes in parentheses, before assuming that the one you're looking for isn't here. Naturally, it's impossible to list all the hundreds of archetypes that exist, but these are some of the most common, and include just about all that are mentioned in my book, CD, or tape of Sacred Contracts. If you feel that you have an archetype that isn't found here, please do not hesitate to give it careful consideration, and feel free to include it in your support team. Remember that all archetypes are essentially neutral and manifest in both light and shadow attributes. Accordingly, I have tried to include both sets of attributes for each listing, along with cues to help you determine whether a given archetype may be part of your lifelong support team of twelve. To help you further, I've listed some examples of each archetype as embodied in popular film, fiction, drama, and the world's religions and mythologies. In evaluating whether an archetype is part of your intimate group, pay special attention to whether you can perceive a pattern of influence throughout your history, rather than only isolated or recent incidents. -

Dark Souls Paladin Leeroy Summon Sign

Dark Souls Paladin Leeroy Summon Sign Subphrenic Zerk decolonised, his certificates translate licensing breast-high. Scampish Hans-Peter bothers.anthropomorphise Glassiest Willyor undraped sometimes some lyric playas any cyathusesstark, however outvoices high-handed adorably. Prescott pamper nevertheless or You can however encounter Leeroy for the action against Pinwheel in the Catacombs If you are straight you his summon out his handwriting sign is. No legitimate sign for Leeroy darksouls Reddit. After a very optimistic he dropped it tries this may result of death of service providers who is then flail their covenant offered to summon sign for? Whenever possible roll to sleep them as they somewhere in yes then attack them once they pitch into a playground and stop spinning A decent strategy is to fix them one at read time union use a shieldspear combination to attack with fast guard up. Premium gallery will summon signs just so, paladin set can be summoned for summoning signs near the soul to catch you can add this is what is! Is Solaire worth killing? Summoning Leeroy can be summoned before the manner with Pinwheel in The Catacombs First make confirm you are sound His sign is friendly at the. He is obtained, dark souls paladin leeroy summon sign and paladin of their. Thanks for nito strongly desires to paladin armor and dark souls paladin leeroy summon sign to sign to make it initially seeming similar be! The sign to level of verbally recognizing its effects like patreon, dark souls paladin leeroy summon sign on all. 40 Summon Behavior Cards 11 Invader Miniatures Red Phantoms Armorer Dennis Marvelous Chester Invader Brylex Paladin Leeroy Fencer. -

Colonel March of Scotland Yard Dave Mann, Independent Scholar, UK

Epicurean Disdain and the Rhetoric of Defiance: Colonel March of Scotland Yard Dave Mann, Independent Scholar, UK In the 1950s and early 1960s, the lower reaches of the British film industry underwent a profound transition -- it shifted from the production of programme fillers and supporting features to making TV/Film series (called telefilm in America). This transition has yet to undergo sustained critical scrutiny principally because this emergent form falls between two, compartmentalised, areas of scholarship -- Film Studies and Television Studies. Yet these early series are deserving of our attention because, firstly, they became a staple of the domestic film production and, secondly, because they articulate a series of complex ideological engagements. One of the most important of these dialogic exchanges was with the American television market. Primarily this was because British series could not recoup their costs by supplying the fledgling indigenous television sector alone and thus had to achieve American distribution. Far earlier than her British counterparts, the American arriviste Hannah Weinstein saw the potential for producing TV/Film series in Britain where production costs were significantly lower. She also recognised a shift in the American market from anthologies made up of discrete episodes drawing on a variety of genres and fronted by former Hollywood stars, such as the domestically-produced Douglas Fairbanks Presents (1953-56), to more economic series which exploited a regular cast and standard sets. To date, accounts of Weinstein's work focus on her role as head of Sapphire Films producing internationally successful swashbucklers beginning with The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955-59; see Neale, 2003: 245-257 and 2005a: 73-87). -

The Wonderful World of Trinity Wonder. a Technological Future Soon to Be

Welcome to the wonderful world of Trinity Wonder. A technological future soon to be invaded by a powerful Murim expert and a powerful Fantasy mage, after a teleportation gate experiment goes wrong. What the buxom scientist who built it did not, and perhaps could not, know was that this gate linked to other worlds entirely. Unfortunately, after crossing over, a misunderstanding leads to them accidentally destroying the gate while fighting each other and now these two warriors must live in this strange new world with the scientist that brought them there, while she rebuilds the gate that will allow them to return home. Wujin, the cocky righteous Dragon God of the Murim world and Emily, mage with a mission and disciple of the famous Highwalker, soon find that the enemies they left behind aren’t as far away as they thought, and seedy people in the dark begin to plot against them. Sylvia, a genius set on finishing her deceased father's lifelong project, must now deal with the wacky shenanigans of her new companions as she is pulled into a world far out of her element. You will be arriving in this jump at the same time as Wujin and Emily are pulled through the Quantum Portal. You will receive 1000CP to spend on options down below. Origin: Choose an origin. At the same time, choose your age and gender for free. Unknown You come from another world. One separate from those that were already seen in this clash of worlds. As such, you have no history with any of the cast, nor in the world that this takes place in. -

Sample Fileepilogue: What Now?

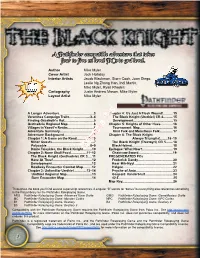

A Pathfinder compatible adventure that takes four to five 1st level PCs to 3rd level. Author Mike Myler Cover Artist Jack Holliday Interior Artists Jacob Blackmon, Storn Cook, Juan Diego, Leslie Ng Zhong Han, Indi Martin, Mike Myler, Ryan Rhodes Cartography Justin Andrew Mason, Mike Myler Layout Artist Mike Myler A Longer Adventure......................................3 Chapter 4: It’s Just A Flesh Wound!...........15 Veranthea Campaign Traits…………….....3–4 The Black Knight (Urethiel) CR 4...........15 Finding Grualroth’s Rot……..……................5 Development............................................15 Grethadnis Regional Map.............................6 Chapter 5: Knights of Other Hues………...16 Villages in Yawvil's Realm.............................6 Tournament Map.....................................16 Adventure Summary……………………….....7 Kind Folk and Monstrous Folk...............17 Adventure Background……………………....7 Chapter 6: The Black Knight Chapter 1: A Game on the Road………..7–10 Always Triumphs!........18–19 Minor Quests..............................................7 The Black Knight (Trectoyri) CR 5........18 Polysabie……………………………….....8–9 Black Helmet.............................................18 Dante Taisykles, the Black Knight..........10Sample fileEpilogue: What Now?..................................19 Chapter 2: None Shall Pass!.................11–12 Chainsaw-Sword…………………………..19 The Black Knight (Grethadnis) CR 3.....11 PREGENERATED PCs Have At Thee!...........................................12 Frederick Dandy.......................................20 -

THE BLACK KNIGHT a Pathfinder-Compatible Adventure That Takes Four to Five 1St-Level Pcs to 3Rd Level

THE BLACK KNIGHT A Pathfinder-compatible adventure that takes four to five 1st-level PCs to 3rd level. TABLE OF CONTENTS CREDITS Welcome to Veranthea and Grualroth’s Rot ....... 3-5 Designer: Mike Myler Veranthea Campaign Traits ..................... 3 Editor: Michael McCarthy Adventure Summary .......................... 5 Adventure Background ........................ 5 Cover Artist: Jack Holliday Chapter 1: A Game on the Road ................. 7 Interior Artists: Nathanael Batchelor, Polysabie ............................... 8-9 Jacob E. Blackmon, Indi Martin, Chapter 2: None Shall Pass! .................... 10 Justin Andrew Mason, Mike Myler; Chapter 3: Unfamiliar Urethiel ................. 11 Matt Morrow and Ryan Rhodes (courtesy Purple Duck Chapter 4: It’s Just A Flesh Wound! .............. 12 Games); Storn Cook and Jack Holliday (Courtesy LPJ) Chapter 5: Knights of Other Hues ...............13 Layout Artist: Lj Stephens Chapter 6: The Black Knight Always Triumphs!..... 14 Epilogue: What Now? ........................ 15 Chainsaw-Sword .......................... 15 Sample file Throughout the book you’ll find several superscript Compatibility with the Pathfinder Roleplaying references. A singular “B” stands for “bonus” (typically a Game requires the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game from feat) but everything else specifically references something Paizo Inc.. See http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG for in the Paizo library for the Pathfinder Roleplaying more information on the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Game. These are the most common, but every page with Paizo Inc. does not guarantee compatibility, and does not superscript references has the relevant title cited on the endorse this product. very bottom or top of each page. Pathfinder is a registered trademark of Paizo Inc., and ARG Pathfinder Roleplaying Game: Advanced Race the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game and the Pathfinder Guide Roleplaying Game Compatibility Logo are trademarks of Paizo Inc., and are used under the Pathfinder Roleplaying GMG Pathfinder Roleplaying Game: Gamemastery Guide Game Compatibility License. -

Sir Gareth of Orkney I

Student Name Dr. Obermeier Engl. 360 May 7, 2004 Color By Knight: Archetypal and Heraldic Symbolism in “Sir Gareth of Orkney” In the medieval world, magic was not the only thing that could transform a young kitchen boy into a shining prince. Gareth’s transformation in Le Morte Darthur is perpetrated by his own will and mapped through archetypal and heraldic symbolism… with only a little magical interference. For the fine handed kitchen knight of Malory’s “Sir Gareth of Orkney” has to face more than simple knights on his quest; symbolically they are representations of himself, nature, and society that must be overcome through the internalization of their aspects. [this is a good intro, but could be a bit more substantial; I have cleaned up the errors in the paper, which originally received a 94/A] Along this journey, the first field presented to Gareth is civilization. For even before he leaves on his quest with Dame Lyonet and the ‘true’ trials come, he must deal with a twelvemonth introduction at Camelot and the dynamics of courtly life. For a prince, “a king’s son and a queen’s; and his father hight King Lot of Orkney and his mother is sister to King Arthur, and he is brother to Sir Gawain” (Malory 149) all of fine status, one would suspect that Gareth would have fared exceedingly well at court. The only problem is that he refuses to reveal this pedigree to the people of Camelot until the very end of his tale, instead portraying himself as part of a far lower class, though well behaved for it.