Prophets Par Excellence in Luke-Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gleaners Bible Studies E5

Gleaners Bible Studies E5 MESSAGES FROM THE PROPHETS Study 1 Jeremiah - God is True Jeremiah chapter 1 while following his ordinary path of duty in Anathoth and Read completely changed his life. Notice verse 5 of chapter 1. Can you imagine the surprise of the prophet when God In our studies in the lives of the prophets we have told him that he was already known and marked out to be already noted at least two vital factors in their work. Each a prophet of the Lord. Jeremiah protests and hesitantly man differed in personality, background and approach. expressed his sense of inadequacy for such a task. But Recognising this, we have seen how God makes use of this does not alter God’s intention. The prophet had to learn the individuality of His servants, fitting into His plans the that God’s command was also God’s enabling. The WORD particular traits of their varying personalities. So we have must be spoken - the TRUE WORD of God. God was going thought of Isaiah the statesman, Amos, the herdsman and to send Jeremiah to His people with a vital message. This Hosea the family man. Our study in the prophets becomes message would “root out”, “pull down”, “destroy”, fascinating as we keep these facts in mind. “throw down”, “build and plant”. (verse 10) Although Jeremiah felt his own complete unworthiness for the task, When we look at the life of Jeremiah, we come to a different God would not take ‘no’ for an answer. The lesson is clear character again. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

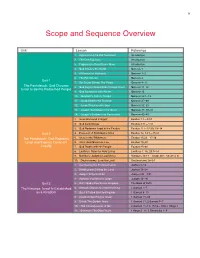

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives Howard R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor College of Christian Studies of Arthur O. Roberts 1996 Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives Howard R. Macy George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/truths_bright Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons Recommended Citation Macy, Howard R., "Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives" (1996). Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor of Arthur O. Roberts. Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/truths_bright/3 This Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Christian Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor of Arthur O. Roberts by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives HOWARD R. MACY will propose in this essay that the lives of the prophets, or more pre cisely, the practical results of the spirituality of the prophets, can guide I our own living as followers of Christ. They can supply insights which can help interpret our experience, and they can hold out vistas of possibili tiesfor growth which we may not yet have realized. As I sometimes warn my students, I should caution that understanding the prophets may corrupt your life. Just about the time you've caught on to what the prophets are doing, you discover that they've caught you. Once you know what the prophets knew by heart, a revolution begins which can not fully be resisted or undone. -

Pdf Israelian Hebrew in the Book of Amos

ISRAELIAN HEBREW IN THE BOOK OF AMOS Gary A. Rendsburg 1.0. The Location of Tekoa The vast majority of scholars continue to identify the home vil- lage of the prophet Amos with Tekoa1 on the edge of the Judean wilderness—even though there is little or no evidence to support this assertion. A minority of scholars, the present writer included, identifies the home village of Amos with Tekoa in the Galilee— an assertion for which, as we shall see, there is considerable solid evidence. 1.1. Southern Tekoa The former village is known from several references in Chroni- cles, especially 2 Chron. 11.6, where it is mentioned, alongside Bethlehem, in a list of cities fortified by Rehoboam in Judah. See also 2 Chron. 20.20, with reference to the journey by Jehosha- to the wilderness of Tekoa’.2‘ לְמִדְב ַּ֣ר תְקֹ֑וע phat and his entourage The genealogical records in 1 Chron. 2.24 and 4.5, referencing a 1 More properly Teqoaʿ (or even Təqōaʿ), but I will continue to use the time-honoured English spelling of Tekoa. 2 See also the reference to the ‘wilderness of Tekoa’ in 1 Macc. 9.33. © 2021 Gary A. Rendsburg, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.23 718 New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew Judahite named Tekoa, may also encode the name of this village. The name of the site lives on in the name of the Arab village of Tuquʿ and the adjoining ruin of Khirbet Tequʿa, about 8 km south of Bethlehem.3 1.2. -

On the Qur'ān and the Theme of Jews As “Killers of the Prophets1

DOI: 10.11136/jqh.1210.02.02 ON THE QUR’ĀN AND THE THEME OF JEWS AS “KILLERS OF THE PROPHETS 1 Gabriel Said Reynolds* Abstract A prominent element of the Qur’ān’s material on the Jews is its report that the Israelites killed prophets sent to them. The Qur’an does not describe the killing of any particular prophet, nor does it attempt to prove in any other way that the Jews have killed the prophets. Instead the Qur’an seems to consider it common knowledge that the Jews have done so as it makes certain inter- religious arguments in this light. However, on the basis of the Hebrew Bible the prominence of this theme in the Qur’an hardly makes sense. None of the great prophets in the Hebrew Bible are killed by the Israelites. In the present paper I argue that this theme emerges from the para-biblical traditions which indeed describe how the Jews killed the prophets whom God sent to them. These traditions are found already in Jewish texts, and they lead Christian authors -- including New Testament authors – to connect the Jewish persecution of Christian believers with their earlier persecution of the prophets who predicted the coming of Christ. This connection is prominent in the anti- Jewish literature of the Syriac Christian authors. The manner in which the Qur’an employs the theme of Jews as killers of the prophets is closely related to that literature. Keywords: Qur’an, Jews, Christians, Prophets, Syriac, Midrash, Ephrem, Jacob of Serug. * University of Notre Dame, [email protected]. -

Zechariah's Word

Zechariah’s Word 1 In the eighth month, in the second year of Darius, the word of the LORD1 came to the prophet Zechariah, the son of Berechiah, son of Iddo, saying, 2 "The LORD was very angry with your fathers. 3 Therefore say to them, Thus declares the LORD of hosts: Return to me, says the LORD of hosts, and I will return to you, says the LORD of hosts. 4 Do not be like your fathers, to whom the former prophets cried out, 'Thus says the LORD of hosts, Return from your evil ways and from your evil deeds.' But they did not hear or pay attention to me, declares the LORD. 5 Your fathers, where are they? And the prophets, do they live forever? 6 But my words and my statutes, which I commanded my servants the prophets, did they not overtake your fathers? So they repented and said, 'As the LORD of hosts purposed to deal with us for our ways and deeds, so has he dealt with us.'" Zechariah 1:1-6 The Veil is Taken Off EACH WEEK IN OUR CHURCH’S WORSHIP SERVICE, we read a portion of God’s law, and then later we read from the gospel. Both wings of the Protestant Reformation (Lutheran and Reformed) taught that there are two basic “words” of Scripture. That is, all Scripture can be divided into two basic categories. These categories are law and gospel. These are not equivalent to OT (law) and NT (gospel), because there is gospel in the OT (Gen 3:15; etc.; cf. -

Headings in the Books of the Eighth-Century Prophets

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Spring 1987, Vol. 25, No. 1, 9-26. Copyright @ 1987 by Andrews University Press. HEADINGS IN THE BOOKS OF THE EIGHTH-CENTURY PROPHETS DAVID NOEL FREEDMAN The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 The present essay is part of a larger contemplated study of the headings or opening lines of several biblical books, and what they can tell us about the purpose and process of scriptural redaction and publication. The project at hand involves an examination of the headings of the four books of the eighth-century prophets, listed in the order in which we find them in the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah, Hosea, Amos, Micah. With slight but significant variations, the headings are formulaic in character, follow the same pattern, and contain the same or corresponding items of information. If we set the introductory lines side by side or organize them in tabular form, as we do on pp. 10-11, we can recognize at a glance both the formulary and the divergences in detail. 1. Structure of the Headings The headings consist basically of two parts, each of which may have a varying number of subdivisions or extensions. Thus, the heading proper consists of a phrase in the form of a construct chain containing two words, the first defining the experience of the prophet 'Most of the headings (or titles) of the prophetic books in the Hebrew Bible, while sharing similar elements, show remarkable diversity. The headings of the eighth-century prophets compared with the other prophetic headings show sufficient similarity to suggest that they were shaped by a common editorial tradition. -

The Spirit of God in the Ministry of the Old Testament Prophets

Leaven Volume 12 Issue 3 The Holy Spirit Article 3 1-1-2004 The Spirit of God in the Ministry of the Old Testament Prophets Craig Bowman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bowman, Craig (2004) "The Spirit of God in the Ministry of the Old Testament Prophets," Leaven: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol12/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Bowman: The Spirit of God in the Ministry of the Old Testament Prophets The Spirit of God in the Ministry of the Old Testament Prophets CRAIG BOWMAN he role of the Spirit of God, more specifically the Holy Spirit, is essentially a NT doctrine. Until recently very few articles and monographs had been written in English on God's Spirit in the OT.I T When included in biblical theologies on the Holy Spirit, the OT material is generally treated in these ways: • the OT references are mentioned in passing in order to reach the outpouring of the Spirit upon the church in the NT, the real experience of the Holy Spirit; • the OT verses specific to the phrase Holy Spirit are viewed as minimal (only three while the NT boasts over 500 occurrences); • assumptions regarding the work of the Spirit-while plentiful in each testament-are typically nar- rowly shaped as reverse analogy where the NT is the beginning point for a Christian understanding of the OT.2 Consequently, most expositions on the Holy Spirit rarely explore in depth OT passages where inexplicit references might suggest a more diverse description and broader activity of the Spirit of God. -

Some Remarks on the Figure of Elijah in Lives of the Prophets 21:1–3

SOME REMARKS ON THE FIGURE OF ELIJAH IN LIVES OF THE PROPHETS 21:1–3 Géza G. Xeravits The prophet Elijah is one of those fi gures of the Hebrew Bible who has continuously attracted the attention of ancient Jewish and Chris- tian thought. This seems to be entirely natural, for we fi nd already in the biblical presentation of Elijah a couple of remarkable char- acteristics, which could inspire the thinking of later theologians and mystics. The end of his earthly career—just like Enoch’s—closes in an uncustomary way: his death is not reported; the Deuteronomist closes the description of his life with the astonishing event of his ascension (2 Kgs 2:9 –13). Furthermore, even the proto- and deuterocanonical Old Testament assumes his activity after his earthly life, relating him as having important tasks during the eschatological events (Mal 3:23–24 and Sir 48:10).1 In this short paper I focus on a relative rarely studied early Jewish work, the Lives of the Prophets, which transmits some remarkable details concerning the birth of Elijah. I dedicate these pages with pleasure to Professor Florentino García Martínez, with whom I had the privilege to work on my doctoral thesis, and who—with his vast knowledge and critical eye—actively contributed to its birth. Narratives of miraculous births are recurring both in the Bible and in the extrabiblical Jewish literature. The Hebrew Bible often relates extraordinary circumstances when speaking about the birth of the patriarchs: we fi nd here and there the presence of angels, or direct divine revelation, or other miraculous events (cp. -

The Narrative Frame of Daniel: a Literary Assessment

THE NARRATIVE FRAME OF DANIEL: A LITERARY ASSESSMENT BY MATTHIAS HENZE Rice Unirversity One of the most popular types of Jewish literature during the Second Temple period was the Jewish novel.* The court-legends about Daniel and his three companions now collected in the narrative frame of the biblical book (Dan 1-6) are a formidable example of this highly pop- ular genre.1 Biblical scholars have long been intrigued by the tales. A principal concern in the scholarly discourse has been the tales' socio- historical origin because, it is assumed, the origin of the texts will undoubtedly yield considerable information about their purpose. The search for origins is inextricably linked to the search for meaning. Yet the quest proves difficult. For one thing, the biblical text provides next to no historically reliable information about its origin and thus offers the investigators little help. Moreover, scholars from a growing number of departments in the Humanities have come to problematize the rela- tionship between the text and the extra-textual reality. While in the past it may have been accepted to assume that there is an "unmedi- ated" connection between the world of a text and that of its histori- cal origin, such an assumption cannot go unchallenged any more. The question of reference is much more complex than traditional biblical scholarship has proposed. * I would like to thank the participants in the Wisdomand Apocalypticismin Early Judaismand Early ChristianilyGroup at the 1999 annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Boston, as well as my colleagues Werner Kelber and Michael Maas, for their most insightful comments on earlier drafts of this I paper. -

The Lives of the Prophets and the Book of the Twelve

Chapter 23 The Lives of the Prophets and the Book of the Twelve Anna Maria Schwemer 1 Literary Character The Vitae Prophetarum (Liv. Pro.) are a small collection of biographical ac- counts of twenty-three Old Testament prophets. It is a document of Jewish origin written in Greek language around the turn of the common era, most likely in Jerusalem.1 The influence of the Septuagint is clear even though some traditions suggest also Hebrew or Aramaic sources.2 Each of the short biographies states the name of the prophet, his origin, place and cause of death, and the location of his tomb. This basic structure is supplemented by legendary material about the prophets, although the pro- phetic writings are seldom consulted. Particularly important in this regard are the prophets’ eschatological prophecies and unusual forms of death. The Liv. Pro. are based on the literary model of the biography (Βίος), a genre that was in use in the Greco-Roman world since the third century bce. It consisted of collections of the vitae of important statesmen, poets or philoso- phers. Not only were the famous biographies written by Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius in circulation, but also less pretentious ones. One such example of a modest form similar to Liv. Pro. has been preserved in P.Oxy. 1800. This papy- rus is a compendium of “Bildungswissen” [educational knowledge] on philo- sophical and literary figures, with a pronounced interest in unusual forms of death.3 In the Greek collections of vitae there are also shorter texts such as the so-called Genos, alongside the longer Bioi.